One morning this past September, Mrs. Mary Scott walked out of her tiny brick house, one hand clutching a plastic tub of birdseed, the other holding on to the front door in case she lost her balance. Taking her time, she stepped off the front stoop and onto a pebbled sidewalk that her husband, Walter, dead now for a decade, had laid down one weekend in the mid-sixties. From out of nowhere, half a dozen doves arrived, soon followed by half a dozen more. “Look at the one that’s all white,” Mrs. Scott said. “Miss Whitey, I call her.”

Suddenly her voice faltered, the doves forgotten. Mrs. Scott had noticed a young man down the block, walking past one of the new three-story townhomes that now line the street, some of them still unoccupied, the builder’s signs advertising wood-paneled ceilings, recessed lighting, and granite countertops. She stared in his direction, her eyes blinking behind her glasses. For a moment, she didn’t seem sure what to do. “Sometimes I see someone and I think it’s my son,” she said. “I think he’s come home.”

Mrs. Scott, who is 83 years old, lives on West Twenty-fifth Street in the Heights, a Houston neighborhood about five miles northwest of downtown. On April 20, 1972, her seventeen-year-old son, Mark, a blue-eyed kid whose cheeks dimpled when he smiled, walked out the front door of that house and was never seen again. Mr. and Mrs. Scott and their younger son, Jeff, called Mark’s friends and classmates, asking if they had seen him. They got in their car and roamed the streets, peering down alleys and stopping at the local drive-in restaurants. They called hospitals to see if Mark had been admitted, and Walter, a self-employed carpenter and handyman, drove to the Houston Police Department to report that Mark was missing.

A few days later, they received what seemed to be a hastily written postcard from Mark. “How are you doing?” he wrote. “I am in Austin for a couple of days. I found a good job. I am making $3 an hour.” His mother and father shook their heads in disbelief. Their son, who was only a junior in high school, had left for Austin without saying a word? They were convinced that something terrible had happened. Mark hadn’t even taken his beloved Honda C70 motorcycle.

Mrs. Scott was then 44 years old, a switchboard operator for Dresser Industries. In those first few weeks, she left work early to wait on her stoop, looking left and right. She walked to the chain-link fence at the edge of the yard, cocked her head, and stared down the street. Some days she would meet the postman at the mailbox to see if he had another postcard.

But Mark never wrote again. He never called. “At night, whenever I heard a noise, I’d get out of bed and walk to the front door,” Mrs. Scott says. “I always prayed he would be there, so I could give him a hug.”

Then, on the evening of August 8, 1973, the Houston television stations cut into their regular programming, and Mrs. Scott, sitting on a flower-print couch in the living room, stared at her black and white screen and sensed that her prayers would forever go unanswered. According to the reporters, a 33-year-old man named Dean Corll had been shot to death at his home in Pasadena, a Houston suburb. The police had learned that Corll had been renting a metal storage shed located just off a narrow, dead-end street about nine miles southwest of downtown. Detectives were at the shed now, the reporters continued, their voices rising, and they were digging up the bodies of teenage boys—all of whom had apparently been murdered by Corll. Checking their notes, the reporters said Corll had once been a resident of the Heights, where he had helped his mother run a small candy factory on West Twenty-second Street. Mrs. Scott grabbed her husband’s hand and said, “Oh, Mark. Our poor Mark.”

By the next day, police officers were exhuming bodies from a wooded area near Sam Rayburn Reservoir, outside Lufkin, and on a beach at High Island, east of Houston. Some of the bodies were covered with a layer of lime powder and shrouded in clear plastic, their faces looking up at the men uncovering them. Others were nothing more than lumps of putrefied flesh. A few still had tape strapped across their mouths; others had nylon rope wrapped around their necks or bullet holes in their heads. One boy was curled up in a fetal position.

Within a week, the remains of 27 young males had been found, a couple of them as young as thirteen, one as old as twenty. The New York Times quickly labeled the killings “the largest multiple murder case in United States history”—the phrase “serial killer” had not yet been coined—surpassing the 13 women choked to death by the Boston Strangler in the early sixties, the 16 people shot by Charles Whitman in 1966 from the Tower at the University of Texas, and the 25 itinerant workers killed by Juan Corona in California just two years earlier. Soon reporters began flying to Houston from every corner of the United States. A few arrived from as far away as Japan and Pakistan. Even Truman Capote, hoping to revive his floundering career and produce his next In Cold Blood, showed up, wearing his signature Panama hat, smoking cigarettes, and being trailed by an entourage of assistants.

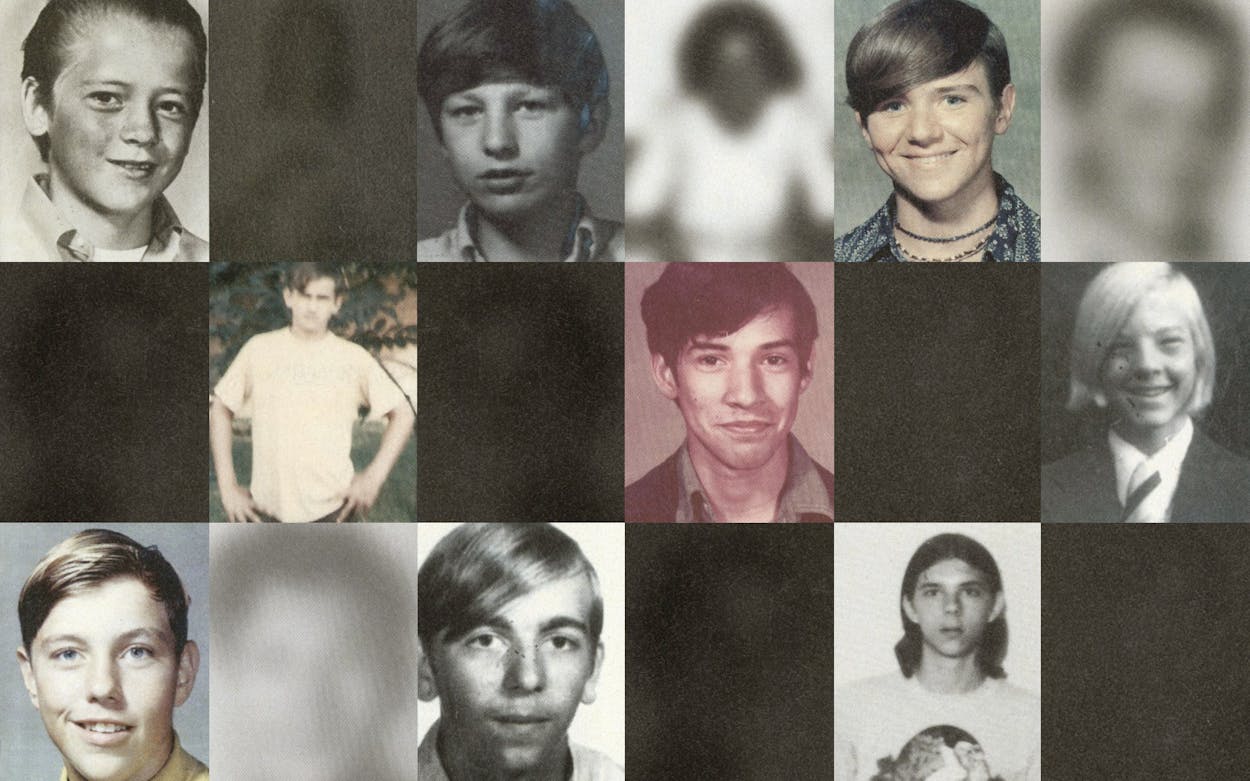

It wasn’t just the number of murders that caught everyone’s attention. Of the victims the medical examiner’s office was able to identify, at least twenty of them had been residents of either the Heights or an adjoining neighborhood. Or they were Houston boys who had been somewhere in the Heights right before they disappeared. All of the Heights victims had gone missing between December 13, 1970, and July 25, 1973. Eleven of them had attended the same junior high. How, Capote and everyone else wanted to know, was it possible that so many boys could have been snatched away from one working-class area of Houston, a mere two miles wide and three miles deep, without anyone—police, parents, neighbors, teachers, or friends—snapping to what was happening?

And why, they asked, had Corll wanted to kill them? Big and broad-shouldered, with thick black hair and sideburns, he was known, in the words of one reporter, as the “pleasant, smiling candy man of the Heights,” always handing out treats to neighborhood children who dropped by his mother’s factory. A police officer who had gone to high school with Corll and married his cousin insisted that he was “a quiet, well-mannered, well-groomed, considerate person.” He had a nice girlfriend, Betty, a single mother who let her children call him Daddy. No one in the Heights could fathom that Corll, who had no criminal record of any kind, could be the worst predator in American history. As one man put it, “He didn’t have no temper.”

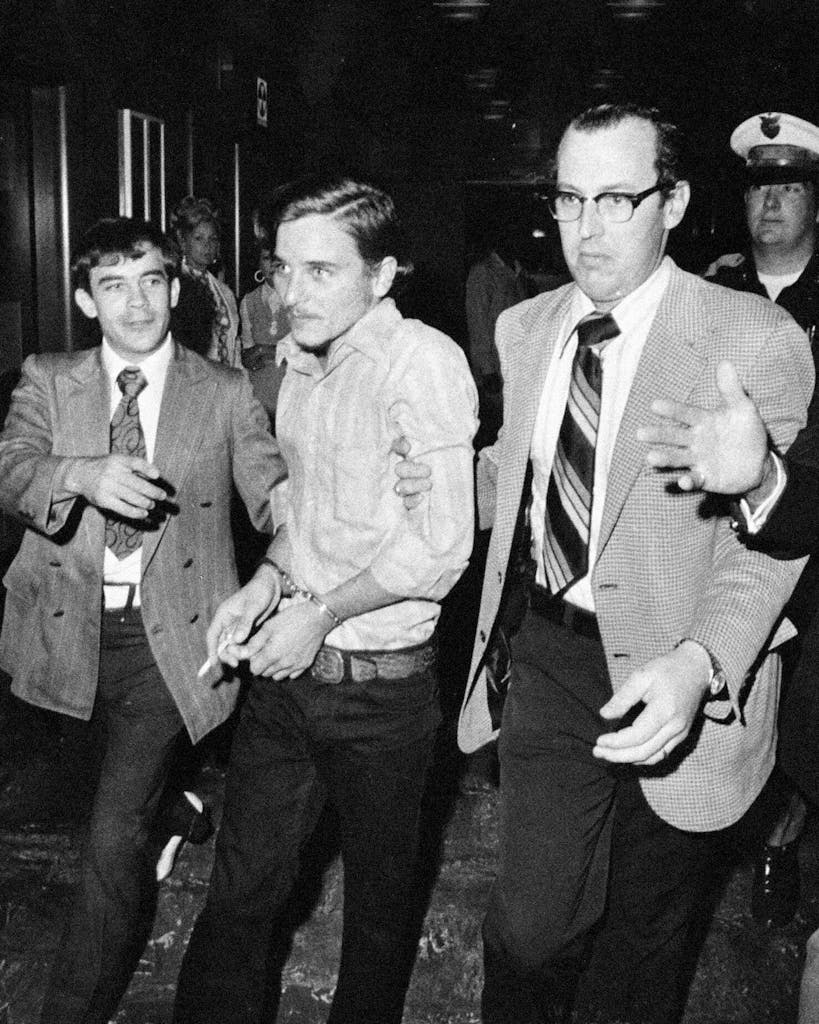

What made the story simply chilling, though, was the revelation that Corll hadn’t acted alone. Two teenagers from the Heights admitted to the police that Corll had recruited them to be his assistants: seventeen-year-old Wayne Henley, a wiry kid with acne on his cheeks and thick brown hair, and eighteen-year-old David Brooks, an ascetic-looking blond-haired youth who wore wire-rimmed glasses. They said they had lured boys into Corll’s Plymouth GTX muscle car or his white van, asking if they needed a ride or if they wanted to go drink beer. After taking the boys to one of Corll’s apartments or rent houses—Corll was constantly moving, sometimes staying in one place for only a few weeks—Henley and Brooks would help Corll strip them naked, tape their mouths, bind their hands and legs, and fasten them with handcuffs to a sheet of plywood that was two and a half feet wide and eight feet long. Often they forced the boys to write a letter to their parents or sometimes even call them, letting them know they were okay and would be back soon.

Then Corll would go to work, pulling out the boys’ pubic hair, inserting a thin glass rod into their penis, or sticking a large rubber dildo into their rectum. “Dean would screw all of them and sometimes suck them and make them suck him,” Henley said in his confession. “Then he would kill them.”

In their confessions, Henley and Brooks mentioned the names of many of the teenagers they had helped murder, several of whom were friends, including Henley’s longtime buddy Mark Scott. They admitted they helped Corll carry the bodies to his car or van, and they helped bury them in one of his private cemeteries. One morning, Brooks said in his confession, he and Henley spent a few hours fishing at Sam Rayburn Reservoir before pulling a dead boy out of Corll’s van and digging him a grave. Although the two teenagers were the products of what were then called “broken homes” (their parents were divorced) and they had dropped out of school, they were hardly regarded around the Heights as troublemakers. Not one person who knew the teenagers understood how they could have turned so quickly into vicious sadists, willing to do Corll’s monstrous bidding.

The most flabbergasting aspect of the entire story, however, is that it is almost completely forgotten today. Although two books about the murders were hastily published, they didn’t stay on shelves for long. (After being hospitalized, supposedly for a pulmonary condition, Capote dropped his project altogether.) Perhaps because the newspapers could find only a handful of grainy black and white photographs of Corll—he never gave an interview, of course—the public soon became fixated on the more-media-accessible killers who followed him, like Ted Bundy, who crisscrossed the country in the mid-seventies bludgeoning and strangling women to death; David Berkowitz, the Son of Sam, who confessed to shooting 6 people in New York in 1976 and 1977; and John Wayne Gacy, the killer clown who broke Corll’s record when he murdered 33 Chicago-area boys between 1972 and 1978.

Even today in the Heights, where a new generation of professionals has arrived to renovate the old frame bungalows or tear them down entirely to build their townhomes, yoga studios, and pet lodges, almost nothing is known about Corll and his two teenage assistants. There are no plaques or memorials to honor the boys who were murdered. Some of the current residents who’ve actually heard about the trio’s rampage assume that it’s nothing more than a bizarre urban legend that began and ended during the Nixon administration.

Yet at least in this case, the past is hardly past. From around the country, aging parents who do not know how to use e-mail still send handwritten letters to the Harris County Institute of Forensic Sciences (the former medical examiner’s office), wanting to know if their sons who went missing in the early seventies might be buried in one of Corll’s cemeteries. They ask if there is any new information about the handful of bodies from the killings that have never been identified. Other parents, who learned from Brooks’s and Henley’s confessions that their sons had been murdered, remain convinced that they were given the wrong remains and buried someone else’s child. One of those parents is Mrs. Scott, who has never known for sure what happened to Mark’s body. “I’ve always wanted to know if he was in his proper resting place,” she said in September as she finished feeding her doves, throwing an extra handful of birdseed to Miss Whitey.

Then, less than a month later, her doorbell rang. Standing on the stoop, wearing scrubs and holding a pouch that contained a DNA test kit, was a woman who introduced herself as Sharon Derrick, a forensic anthropologist from the Institute of Forensic Sciences. Mrs. Scott escorted Derrick into the living room. “I want to try to help you,” Derrick said.

For a long time, the frail, white-haired widow said nothing. Then she put her hands over her eyes so that Derrick couldn’t see her tears.

My fourteen-year-old niece came to visit me the other day,” says Wayne Henley, sitting in the visiting area of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice’s Michael Unit, in Tennessee Colony, outside Palestine. “She asked me if I really had done all the things she had been reading about on the Internet. I looked at her and said, ‘Honey, I wish I could explain it to you.’”

He’s now 54 years old, five feet five inches tall, about 150 pounds. His hair is thinning, and he wears reading glasses. He’s been up since five o’clock, working his shift at the prison laundry and dabbling on a painting of a landscape dotted with pine trees in the craft shop. “I try to keep myself busy, and I try not to sleep much,” he says. “I don’t like dreaming about the old days.”

In 1974 Henley received a life sentence for his role in the murders. A year later, David Brooks got his own life sentence and was sent to the Ramsey Unit, south of Houston. Brooks, who still has a touch of blond in his now closely cropped hair, has never spoken publicly since giving his confession. “I sent him a letter once, asking how he was doing,” says Henley. “He wrote back—he typed his letter and didn’t sign it—saying, ‘Let’s stay in touch.’ But we never did. I mean, in the end, what were we going to say to each other—how we wished we had never met Dean?”

In the mid-sixties, when he was either ten or eleven years old, Brooks stopped at the Corll Candy Factory, a small warehouse with an office in front and a loading dock in back, which was just across the street from his elementary school. “David’s parents were divorced. His mother was in Beaumont, and David was living alone with his father, Alton, a very tough, redneck paving contractor,” says Brooks’s former attorney, Jim Skelton, who’s still practicing in Houston. “I don’t think Alton really liked David all that much because he was a sickly kid who wore those hippie glasses. And here came Dean, who didn’t call him a sissy. David idolized him. He told me that Dean was the first adult male who didn’t make fun of him.”

Raised in Indiana and Tennessee, Corll had come to Texas with his mother and siblings when he was sixteen. In 1962 the family moved to the Heights so his mother could open her candy factory, which specialized in divinity, pralines, and pecan chewies. Corll ran the assembly line, and in his free time, he not only handed out candy to the kids but invited them to a back room in the factory, where he had set up a pool table. He gave the kids rides on his motorcycle, and he outfitted his van with cushions, carpets, and a television set so he could take them to picnics at the beach.

As far as Heights parents were concerned, Corll was a perfect gentleman. They regarded his fondness for children to be no different from what they would find in a respectable scoutmaster. One day, a kid named Malley Winkle told his mother, Selma, that he had been given a job sweeping up pecan scraps and peeling caramel off the floor at the factory. Selma, who was divorced and worked nights as a nurse’s aide, checked out the factory herself and was so taken by Corll that she accepted his offer to work part-time in the afternoons.

No one adored Corll more than his petite, blue-eyed mother, Mary, who was known around the Heights both for her entrepreneurial skills and her fondness for marriage. She had twice married and divorced Corll’s father, who lived in Pasadena, where he worked as an electrician; then she had married and divorced a salesman. Later she had impulsively married a merchant seaman she had met through a newly opened Houston computer-dating service (she filled out a questionnaire; her answers were then fed into a giant mainframe computer; and after several days, the computer produced a list of potential dates for her based on other applicants’ questionnaires). Perhaps the reason Mary was so unlucky in love was because no man was as important to her as her son, whom she depended on to run the candy factory. Corll, in turn, loved pleasing her. In 1965 he successfully applied for a hardship discharge from the Army, where he had compiled an exemplary record in the radio repair school at Fort Hood, because he said his mother needed him back home.

At one point, Mary’s third husband, the merchant seaman, told his wife that he suspected Corll might be homosexual because of the number of young boys he invited over to the candy factory after hours. She refused to believe it, later telling a reporter for the Houston Post that her son was “loyal, obedient, helpful, loving, and a good normal boy.” His one problem, she said, was that “he was the kind of person who never wanted to get close enough to anyone so they could get ties on him. He had seen so many broken marriages.” True to form, she divorced the merchant seaman in 1968, and based on her visits to Houston psychics, who told her that she needed to get as far away from him as possible, she closed the candy factory and moved to Colorado.

No doubt to his mother’s surprise, Corll told her he would be staying. He got a job working as an electrician at the Houston Lighting and Power Company, and by 1970 he had moved to an apartment about five miles southwest of the Heights, on Yorktown Street. The apartment was located a few blocks from the Galleria, a 600,000-square-foot indoor luxury shopping mall, complete with an ice skating rink in the center and Neiman Marcus as its anchor, that was preparing to open in November. It was a giddy time in Houston: Boosters were calling the city “the future of the United States.” Over at the Texas Medical Center, rival surgeons Denton Cooley and Michael DeBakey were pioneering heart transplant surgery, and at NASA’s giant Manned Spaceflight Center, flight directors were guiding Apollo astronauts to the moon. The Astrodome, which had opened in 1965, was still being called the Eighth Wonder of the World. People were flooding into Houston, the population rapidly approached two million, and the apartments around the Galleria were swarming with single people hoping to someday make their mark on the world. Living less than a mile away from Corll in the snazzy Chateaux Dijon apartment complex, which offered six swimming pools and all-day water volleyball games, was the well-known Houston bachelor George W. Bush, who was then driving a Triumph sports car, chasing women, and flying jets for the Texas Air National Guard.

But Corll wasn’t exactly like his neighbors. At some point after his mother left Houston, he decided to embrace a compulsion he had apparently kept secret for years. He began inviting teenage boys over to his apartment, some of whom he had been eyeing since his days at the candy factory. One of those boys was David Brooks. After he arrived, Corll persuaded him to pull down his pants, at which point Corll dropped to his knees and began performing what the Texas criminal statutes at the time called “oral sodomy.”

According to those who knew Brooks, the introspective young teenager was not gay; in fact, he had a girlfriend who lived in the Heights. “But you have to understand that Dean had become David’s father figure,” says Brooks’s attorney, Skelton. “He had taken care of him, given him money when he needed it, and let him stay with him whenever David needed to get away from his real father. You know, a man like that can have a lot of influence over a young, insecure boy.”

It wasn’t long, though, before Brooks realized that Corll was driven by much darker needs. In mid-December, Brooks, who was then fifteen, walked unannounced into Corll’s apartment. In the confession he gave police two and a half years later, he said he saw two naked boys tied to Corll’s bed. Corll, also naked, was molesting them. “What are you doing here?” Corll snapped, and Brooks turned around and left. Later, he said, Corll told him that he was part of a gay pornography ring and that he had been paid to send those boys out to California to pose for photos. At some point, Brooks said, Corll changed his story. He told Brooks he had killed the boys and buried them in his storage shed.

It’s likely those two boys were Jimmy Glass and Danny Yates, best friends who lived in the Spring Branch area of Houston. Both were fourteen, and they had come to the Heights on Sunday night, December 13, with Jimmy’s father and older brother, Willie, to attend an antidrug youth rally and worship service at a church called the Evangelistic Temple. Jimmy and Danny sat toward the front. “During the middle of the service,” recalls Willie, who is now a 64-year-old retired Houston firefighter, “I saw them walk up an aisle, as if they were going to the restroom. And that was it. They basically vanished into thin air.”

Jimmy, the son of a mining engineer, was a handsome teenager who wore trendy, loud-patterned shirts with wide lapels, leather necklaces dotted with beads, and a leather jacket with fringe that hung off the sleeves. He brushed his thick brown hair slightly over one eyebrow, which drove girls wild. Danny, the son of a union electrician, was equally good-looking, “with curly brown hair and blue eyes and peach fuzz on his face,” says Bettye McCool Johnson, his girlfriend at the time. Now 54, Johnson lives in a small town in Mississippi, where she is married and has a teenage son of her own, but she still keeps two photos of Danny in her jewelry box. “He was my first love,” she says. “We were in a laundry room at our apartment complex when he first kissed me—the kind of thing a girl never forgets.”

To this day no one knows how Corll met the boys and persuaded them to ride away with him. Danny’s older sister Cyndi says Danny and Jimmy had once talked about a man, whose description, she later realized, matched Corll’s, giving them a ride to a movie theater and stopping to buy them beer.

What is known is that the police barely investigated the boys’ disappearance. In that era, all the missing persons reports for juveniles throughout Houston were divided among various officers in the juvenile division. The officer who received the report on Jimmy labeled him a runaway after learning he had previously left home and stayed with friends because he had been having arguments with his father about such issues as the length of his hair. The officer who got Danny’s report also labeled him a runaway, after finding out that someone thought he’d seen him at a house where runaways often gathered.

When the parents protested, the officers said that all sorts of kids were hitting the road, hitchhiking across the country, joining communes and being part of the “hippie” movement. The investigators said that unless there was clear evidence of foul play, no official search could be conducted. But they promised the families that if their sons were spotted on the streets, they would be told to go back to school.

The families were on their own. Every weekend the Glasses and the Yateses drove around Houston, posting flyers with their sons’ pictures. Willie placed an ad in the weekly Greensheet newspaper written directly to Jimmy, promising him a motorcyle if he would come home. At one point, Danny’s father drove to Monterrey, Mexico, after getting a tip that Danny had been seen there. “Dad began to fall apart right in front of our eyes,” recalls Cyndi. “He was so worried that Danny had left because he had been too hard on him.”

After the murders of Danny and Jimmy, Corll moved to the Place One Apartments on Mangum Road, five miles northwest of the Heights, and on January 30, 1971, he struck again. But this time he had a helper. He and Brooks drove into the Heights and saw two boys, fifteen-year-old Donald Waldrop and his thirteen-year-old brother, Jerry, who were on their way to a bowling alley. They ended up at Corll’s new apartment. There, Brooks said in his confession, he watched as Corll strangled them.

Although the Waldrops’ home was only half a mile from the church where Jimmy and Danny disappeared, the police still did not investigate. The Waldrop brothers’ father, Everett, a burly, divorced construction worker, later told the Houston Chronicle that he filled out missing persons reports at the police department, then “camped on that police department door for eight months. I was there about as much as the chief was. But all they said was ‘Why are you here? You know your boys are runaways.’”

The murders would have stopped right then, of course, if Brooks had simply gone to the police. But according to Skelton, the teenager did not have the inner strength to turn in his father figure. Not sure what else to do, Brooks dropped out of Waltrip High School, where he was a freshman, and began spending more time with Corll. As a reward for his loyalty, Corll gave Brooks a green Corvette as a sixteenth-birthday present. “Dean had David exactly where he wanted him,” says Skelton.

On March 9, Corll and Brooks spied fifteen-year-old Randell Harvey, who was riding his bike to work at a Fina station. Brooks, who knew Harvey well, was probably the one who persuaded the teenager to throw his bike into the back of Corll’s vehicle and ride with them. Corll took Harvey to his apartment, raped him, tortured him, and shot him in the head. Then he and Brooks took Harvey’s body to the storage shed.

Two and a half months later, they went after two boys on the north side of the Heights who were walking to the neighborhood swimming pool. One was sixteen-year-old Malley Winkle, who years earlier had worked at the Corlls’ candy factory with his mother. The other was fourteen-year-old David Hilligiest, who had gone to the candy factory one day as a boy and spent so much time there that his mother had shown up and made him come home. They were strangled at Corll’s apartment and buried in the storage shed as well.

When the officers in the juvenile division heard that Malley had made a quick phone call to his mother, Selma, the night he and David disappeared, telling her he was at the beach town of Freeport swimming with friends, they assumed the boys were runaways and that the matter was resolved. But David’s parents, Fred and Dorothy, refused to believe that their son had taken off without telling them. The family was preparing to leave the next day for a Hill Country vacation. David had already packed his clothes and had $20 sitting on his dresser to spend during the trip. Dorothy, a soft-spoken homemaker, and Fred, who worked for the city striping streets, got in their Ford Galaxie and raced to Freeport, checking the beaches and showing David’s photo to everyone they met.

After they returned to Houston, the Hilligiests and Mrs. Winkle, who lived directly behind them, printed five hundred posters offering a $1,000 reward for information regarding David’s and Malley’s whereabouts. The Hilligiests then borrowed money from a credit union to hire a private investigator, who told them that the boys might have been abducted by a man called Chicken Joe, who reportedly provided male prostitutes to homosexual clients. One night, Dorothy and Fred and a couple of their kids drove over to the city’s Montrose area and sat outside a gay bar called the Silver Dollar Saloon, watching the door, hoping to see David being taken in or out.

As the weeks dragged on, Dorothy called the police constantly, passing on any rumor she heard and suggesting potential witnesses for them to interview. One day, she told the police that she had learned that Malley had a friend who drove a Plymouth GTX. She added that she had seen a GTX puttering through the neighborhood with the license plate TMF 724. If an officer had bothered to look into the matter, he would have learned that the car belonged to Dean Corll.

One of the neighborhood boys who came to the Hilligiest’s home to inquire about David was fifteen-year-old Wayne Henley, who lived half a block away. He asked Mrs. Hilligiest for some posters that he could put up around the Heights.

Compared with the more introspective Brooks, Henley was a brash teenager who had once been brought up on a juvenile assault charge. He drank beer, smoked pot, and chased girls, and he could usually be found at one of the neighborhood hangouts—the swimming pool, the Long John Silver’s on Twenty-third, or the Jack in the Box on Twentieth.

Like Brooks, however, Henley had endured a difficult relationship with his father, who, according to published reports, would get drunk and physically assault his wife and children. After Henley’s parents divorced, in 1970, he dropped out of junior high and began working part-time to help his mother. When Brooks, whom he had known for a few years, introduced him to Corll in 1971, Henley was impressed.

“Maybe Dean was considering me as one of his next victims,” Henley says in the penitentiary visiting room. “But we hit it off. He was this smart, clean-cut, nicely dressed man. He listened to me. He explained things to me.”

Henley puts his chin on his fist and stares at a wall. “I’ll be honest with you, it was important that Dean liked me. He was kind.”

The truth was that even though Corll had been torturing and killing boys, no one realized anything was amiss. His co-workers at Houston Lighting and Power always had good things to say about him, and the manager of one apartment complex where Corll had lived and committed murders called him “as good a tenant as we’ve ever had.” When he began to come around the Henley house, he worked on Mrs. Henley’s car and got along so well with all the Henley boys that a charmed Mrs. Henley invited him to Easter dinner.

And then there was Betty Hawkins, the single mother who first met Corll when she worked at the candy factory and who started dating him in 1968. No, she later told police, he wasn’t sexually aggressive with her. Once, when they were in bed, they began to have intercourse, but he stopped because he said he just “didn’t feel like it.” Still, she said, he was a wonderful man who wanted to settle down and get married, and she never considered it odd that most of their dates were in the presence of her children or with Brooks and Henley tagging along.

Henley insists that when he went to visit the Hilligiests to pass out posters, he too was unaware that Corll had a secret life. He says Corll slowly lured him into his orbit by first telling him that if he ever had anything to sell to make some money to help out his mother, even if it was stolen, Corll could unload it. Then Corll told Henley the same story he had once used on Brooks about belonging to an organization that sold boys into a homosexual porn ring in California. Corll promised Henley $200 for every boy he brought to him.

Corll had made an excellent choice for his second accomplice: Henley seemed to be thrilled by the idea of being part of a mysterious crime ring, something that went far beyond his routine life in the Heights. Driving around with Corll one afternoon, he saw a teenager with long hair, asked him if he wanted to smoke some pot, and soon had him in the car and at Corll’s apartment. Henley then left. The next day, Corll paid him $200. “A day or so later I found out that Dean had killed the boy,” Henley said in his confession. “I found out that Dean screwed him in the ass before killing him.”

Just like Brooks, Henley didn’t go to the police. Even when Corll told him that he had abducted his childhood friend David Hilligiest, Henley didn’t back away. And when Corll pushed Henley to bring him another boy, he picked Frank Aguirre, a good friend who worked at Long John Silver’s. He met Aguirre at the end of his night shift and brought him to Corll’s apartment, where Corll and Brooks were waiting. They started playing the “handcuff game” to see who could get out of a pair of handcuffs. When Aguirre put on the handcuffs, Corll dragged the teenager into the bedroom and, according to Henley, “had his fun with him.” After Aguirre was strangled to death, the trio took him down to High Island for his burial.

Henley then brought his friend Mark Scott to Corll’s. (Henley, Mrs. Scott would later recall, had once come to a party Mark had thrown at their house and had had such a good time he was the last to leave.) According to Brooks’s confession, they were trying to tie Mark’s hands when he grabbed a knife and stabbed at Corll, catching his shirt but barely breaking the skin. Corll wrestled with Mark while Henley ran out of the room to get a pistol. He pointed the gun at Mark, who, said Brooks, “just gave up.” Corll and Henley then strangled him with a cord.

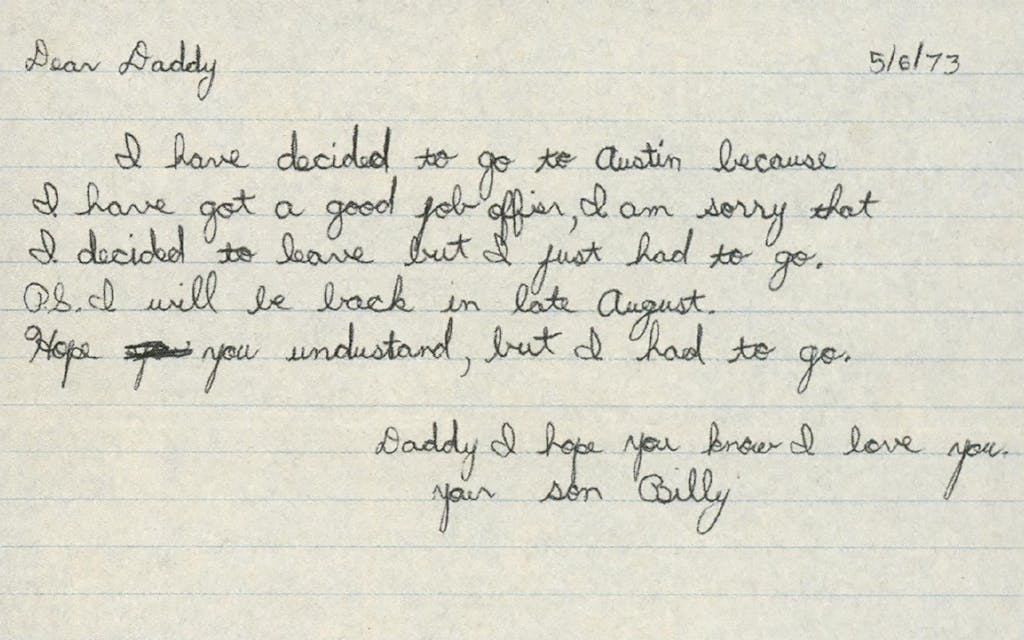

By late 1972, Corll and his teenage henchmen had become a finely tuned killing machine. One afternoon, they brought down seventeen-year-old Billy Baulch, who used to sell Mrs. Corll’s candy door-to-door, and his sixteen-year-old friend Johnny Delone after the two had left Baulch’s home to buy soft drinks. Fourteen months later, Corll, Henley, and Brooks grabbed Billy’s younger brother Michael, who was on his way to get a haircut. They captured and killed a twenty-year-old father who had been living in the Heights and was hitchhiking home to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, to see his wife and new baby. They snatched Homer Garcia, a boy from southwest Houston who was attending a driver’s education class with Henley, and they carted off two boys who had just moved into an apartment across the street from Henley’s house. One fifteen-year-old-boy, Billy Lawrence, whose dad worked in the mailroom at the Houston Post, clearly sensed that he was about to be killed. In the note he was forced to write to his father, promising he would be back in late August, he added at the very end, “Daddy, I hope you know I love you. Your son, Billy.”

Lawrence was kept alive for three days on the plywood because, Henley later said, Corll “really liked him.” Apparently, Corll didn’t like Rusty Branch, the son of a Houston police radio technician. Corll severed Branch’s genitals with a knife and placed them in a plastic bag, which he buried next to the body.

In the summer of 1973, Corll moved into the small Pasadena home owned by his father, who had remarried and was living elsewhere in town, and his appetite became even more voracious. “It was like a blood lust,” says Henley. “Dean would make these short, jerky movements; he’d start smoking a cigarette, which he usually never did; and he’d say he needed to do a new boy.” Between June 1 and August 4, they killed eight boys, five of whom were from the Heights—and still the police, the neighborhood’s residents, and the news media were not putting two and two together. “I’ll never forget one mother coming up to the newsroom on a Saturday afternoon,” recalls Tom Kennedy, a retired Houston Post reporter. “She asked for me because I had just discovered the identity of a hobo who had been run over, and she began begging, almost hysterical, to help her find her son. But it was one of those things we never got around to doing.”

In that era, of course, there were no computers at the police department that would have alerted officers to the number of missing boys. There were no Amber Alerts being broadcast that would have set off alarms with the public, no Internet that would have quickly spread community gossip. As a result, parents who had lost sons on one side of the Heights had no idea that there were parents on the other side of the Heights who had also lost sons.

Indeed, if Corll had been able to maintain his alliance with his accomplices, there’s no telling how long his killing spree might have lasted. But that summer Brooks began to break away. He married his girlfriend after she got pregnant, and they moved into an apartment outside the Heights. Henley too tried to put some distance between himself and Corll, attempting to enlist in the Navy. But he was rejected because of his limited education. “I couldn’t leave anyway,” Henley says. “If I wasn’t around, I knew Dean would go after one of my little brothers, who he always liked a little too much.”

On August 8, Henley arrived at Corll’s with his buddy Tim Kerley and his new girlfriend, Rhonda Williams, a popular girl from the Heights whose previous boyfriend had been Frank Aguirre, whom Henley had brought to Corll more than a year before.

“Wayne would always tell me that I shouldn’t keep waiting for Frank to come back, that he had a feeling he was gone, but I never thought that he might actually have any idea why Frank wouldn’t come back,” says Williams, who lives in West Texas.

Henley insists he didn’t bring his friends over to Corll’s to be attacked. It was “just supposed to be a night of fun,” he says, adding that he only had Williams with him because she had been arguing with her father. In the living room, they drank beer, and Henley and Kerley “bagged” some paint (sniffed the fumes of acrylic spray paint out of a paper bag). But after they fell asleep, or passed out, Corll went on the attack. He hog-tied all three of them and gagged Kerley and Williams. He kicked Williams over and over in the ribs, then he carried Henley into the kitchen to let him know just how angry he was that Henley had brought a girl to his home.

After Henley promised to murder Williams, Corll untied him. They returned to the living room, Corll carrying his .22 pistol and Henley a knife with an eighteen-inch blade. Corll first dragged a terrified Kerley to a back bedroom, then returned for Williams. He tied both of them to his torture board and started to sexually assault Kerley. A sheet of plastic covered the floor. Suddenly, Henley grabbed Corll’s gun. “He aimed it at Dean,” says Williams, who regularly visits a psychiatrist to deal with the post-traumatic stress disorder she says she still endures from that night, “and he said, ‘I can’t go on any longer. I can’t have you kill all my friends.’ And he shot him. Whatever evil was in Wayne, there was still some good in him, and finally the good won. Wayne saved my life, and he saved Tim’s life too. Wayne killed the devil.”

When detectives began interrogating Henley about Corll, asking why he kept handcuffs, the plywood board, and the plastic sheet in the bedroom, Henley no doubt panicked. Had he not said anything, it is possible that the police would never have learned about the murders. Instead Henley let slip that Corll had once bragged about killing boys and burying them in a storage shed. When the police arrived at Southwest Boat Storage, a dry-land marina, the detectives opened the windowless stall number eleven, and they started digging. They found the first body in a matter of minutes. Trying to get the carrion-like odor out of his nose, thirty-year-old detective Larry Earls chain-smoked cigarettes, but his hands were so filthy that someone else had to put them in his mouth.

The police allowed the reporters to walk right up to Henley, who was standing outside the storage unit, and interview him. A television reporter even filmed Henley using a radio phone to call his mother. He cried into the receiver, “Mama! Mama! I killed Dean!” Most of the reporters felt sorry for him. Ann James, the Post’s police reporter, later wrote that she thought of him as “a kind of folk hero who had slain the dragon.” That night, when the police sent out for fried chicken, she made sure Henley got his share.

By the next day, however, Henley was admitting his involvement to the Pasadena police. Soon after, Brooks was escorted to the Houston Police Department by his distraught father, who told detectives that his son also had something to say. Henley showed the police the burial site at Sam Rayburn Reservoir, then he and Brooks took them to High Island. Besides an army of reporters watching the diggings at the beach, there were bikini-clad girls and their boyfriends, along with young parents and children with plastic pails and shovels. At one point, a black Chihuahua jumped in one of the graves and started barking. Over at NASA, Mercury astronaut Deke Slayton ordered a helicopter containing infrared equipment to fly over the beach to see if it could spot other bodies.

Some of the more recent victims were quickly identified. One of those found under the storage shed, Marty Jones, who had been murdered in late July, turned out to be the cousin of homicide detective Karl Siebeneicher, who happened to be on the scene. (Devastated, Siebeneicher ended up committing suicide in 1977.) Other bodies were able to be identified because a Social Security card or driver’s license was found near their decomposed remains. Jimmy Glass’s family was able to identify him only because his beloved leather jacket was next to his skeleton.

Soon reporters were fanning out through the Heights, knocking on doors. Josephine Aguirre, a hairdresser who had spent the past year and a half burning a candle in hopes that her son Frank would come home, had already lost a son, Ronnie; in 1969 she had accidentally run over him in front of Helms Elementary. Not sure what to say to the reporters about her latest loss, she broke down in muted sobs. Luis Garcia, the father of Homer, who had attended a driver’s education class with Henley, was just returning from South Texas, where he had buried his mother, who had suffered a debilitating stroke after hearing the news that her grandson was missing. Not long after Luis pulled into his driveway, a police officer arrived to tell him and his wife, Doris, that Homer’s body had been identified as one of Corll’s victims. Doris could not sleep for days. She kept dreaming that her son had been buried alive and was trying to claw his way out.

Throughout the summer and into the fall, families huddled around open graves at Houston’s cemeteries, burying their boys. Trying to beat back her despair, Betty Cobble, the mother of one of the victims, returned to her job delivering flowers, only to find herself providing arrangements at funerals for other victims. Six months after Danny Yates’s funeral, his parents moved to another part of Houston, hoping that a fresh start would ease their suffering. It didn’t. Not long after they settled into their new home, they divorced.

The Waldrop brothers’ father, Everett, the construction worker, moved to Atlanta, which didn’t help. There he read Brooks’s confession, which had been reprinted in a newspaper. Everett learned he had been working on a new apartment complex directly across the street from Corll’s Place One apartment. “Maybe he had them in the apartment when I went to work,” Waldrop said to the Chronicle. “Maybe they were being tortured right next door and I didn’t know it.”

Some parents turned to pills or alcohol to cope with the pain. Ima Glass, Jimmy’s mother, spiraled out of control. “Many, many times, she’d see a teenager hitchhiking on another side of the freeway and she’d shout, ‘That’s Jimmy! We’ve got to turn around,’ and to keep the peace, my dad would turn around, every time,” says Willie Glass. “Then one day she got a gun and grabbed my younger sister Pamela and dragged her to a back bedroom. When the SWAT team arrived, she fired a shot into the floor and yelled, ‘They’re not going to steal Pamela from me like they did my Jimmy!’ We got the pistol away from her and took her to the Harris County psychiatric unit. She was never the same, and neither were the rest of us. Dean Corll didn’t just kill twenty-seven boys. He killed twenty-seven families.”

But was it only 27 boys? One of the bodies at High Island was identified as Jeffrey Konen, who had been a salutatorian at St. Thomas High School, a private Catholic school west of downtown Houston, before he enrolled at the University of Texas. On September 1, 1970, about three months before Brooks first saw Jimmy and Danny tied up in Corll’s bed, the eighteen-year-old Konen had hitchhiked from Austin to Houston to see his girlfriend. He got a ride to the Galleria area, and the last time he was seen, he was hitchhiking again, looking for another ride to his girlfriend’s.

If Corll had been able to pull off that killing by himself—as well as the murders of Jimmy Glass and Danny Yates—didn’t it seem likely that he had hunted others on his own? From 1968 to 1970, a few thousand missing persons reports came into the juvenile division of the Houston Police Department. Surely some of those kids were missing because they had run into Corll.

The authorities did dig up the backyard of the Pasadena home where Corll was living, and they searched behind the old candy factory. But only a week after the first bodies were found, the authorities called off the excavations. The Chambers County sheriff who oversaw the High Island diggings said, inexplicably, that he had decided to stop the searches until he received definite information on the location of other graves, apparently never considering that there could have been more bodies that Brooks and Henley did not know about. “It always bothered me,” says Larry Earls, the young homicide detective. “Henley and Brooks told us that they thought there were more bodies, and there were other places where we wanted to dig, but we were told no.”

Bob Wright, the executive director of marketing and communications at Stephen F. Austin University, in Nacogdoches, who was a Houston radio reporter in 1973, says that he was told by a detective that once the body count surpassed the U.S. mass murder record, the excavations were halted. Did civic leaders want the search stopped because they were concerned about how high the count would go? Beating the record by just one or two bodies, after all, was a lot less humiliating than beating it by ten or fifteen.

But in the end, the number didn’t matter. America’s city of the future got hit with a torrent of negative publicity. The Vatican’s daily newspaper, L’Osservatore Romano, published an editorial that said that the Houston killings belonged to the “domain” of the devil, and even Izvestia, the government newspaper of the Soviet Union, got in a shot at Houston, claiming that “indifference” and “murderous bureaucracy” were the reasons the killings had gone on for so long. Furious, the city’s domineering police chief, Herman Short, held a press conference in which he suggested that the boys were mere runaways whose parents didn’t do their best to look after them. He angrily declared that reports of “links” among the victims and the killers were a myth “created by the media.” While he was at it, he took his own shot at Izvestia. “I wonder if they’d like to write a little story about the number of people the government has killed over there—taking their property and annihilating them,” he said.

Mayor Louie Welch defended the chief, bluntly declaring that “the police can’t be expected to know where a child is if his parents don’t.” Welch simply didn’t know what he was talking about. Though it was true that some of the boys had run away from home for brief periods and others had gotten into minor trouble (Mark Scott had once been arrested for carrying a knife, for example), none of them had gotten into serious trouble. Many were just like David Hilligiest, straight-arrow, all-American kids who rarely missed a day of school.

Nevertheless, the teenage runaway story got traction. Governor Dolph Briscoe appealed to runaway teenagers in Texas to contact their parents and let them know they were “alive and well,” and a young senator from Minnesota, Walter Mondale, asked Congress to allocate $30 million over three years to set up a nationwide system of halfway houses for runaway teenagers so that they would have a safe place to go and not end up in the hands of a killer like Corll. Meanwhile, when a California legislator learned that the sex-education textbook used in the state’s schools—Human Sexuality, written by University of Houston psychology professor James Leslie McCary—had been found among Corll’s belongings, he wrote Governor Ronald Reagan a letter, demanding that the book be withdrawn from California schools, in part because it suggested that homosexuality was not an abnormal behavior. “Perhaps you should take a trip to Texas,” the legislator wrote Reagan, “and ask the parents of the 27 young boys if the unusual sexual expressions [Corll] engaged in should be considered abnormal.”

The one thing Chief Short did do, in a misguided attempt to make sure such crimes didn’t happen again, was order his officers to raid the city’s gay bars. “They thought we were all child molesters and killers,” says Ray Hill, one of the city’s first gay activists. Some residents, claiming they were afraid that “other sex deviates” might be operating in the neighborhood, circulated a petition asking the city council to impose a nightly curfew on juveniles, forgetting that almost all of Corll’s abductions took place in broad daylight.

In those years, of course, plenty of people tended to believe, falsely, that homosexuality was linked to pedophilia. But neither could begin to explain what Corll had done. How had a smiling mama’s boy transformed himself into a colossal monster? Did he feel such a sense of shame over his own desires that he ended up despising the very objects of his affection? Is that also why he tortured the boys, because he needed to unleash his fury at them for feeling that desire in the first place?

“I think ol’ Dean tried for years to be a normal person, to have a relationship with a woman, to do everything his mother wanted him to do,” says David Mullican, a plainspoken 71-year-old retired Pasadena homicide detective who investigated the killings. “And all I can tell you is, something came unleashed inside him. Madness, maybe. Or evil.”

Sitting one afternoon at Peppers restaurant in Pasadena, eating a chicken-fried steak, his belly straining at his shirt buttons, Mullican pulls out some photos of himself from 1973, standing beside other cops who worked the case. In the photos, he’s thin and 33, wearing bell-bottoms, a white belt, and a striped shirt with a tie that doesn’t quite reach his navel. “I can go back to that first day at the storage unit when we started digging,” he says, “and just like that, the smell comes back to me, the smell of all those rotting . . .”

Unable to finish his sentence, he puts down his fork and doesn’t eat another bite. He sifts through his photos again. “How that man was able to go out to that storage shed, time after time, and bury one more dead boy is something I’ll never understand,” Mullican says after a few seconds. “You get close to evil like that, no matter how long ago it was, and it never leaves you.”

For weeks the story of the murders stayed on the front pages of the Houston newspapers. To great media fanfare, Corll’s mother arrived from Colorado and announced that her son had to be innocent because he would not have buried bodies at the same boat stall he loaned out to friends of the family to store their furniture. Then, the twelve grand jurors who indicted Henley and Brooks for murder issued an explosive report criticizing the police and the district attorney, saying their investigation left unexplored “the possible involvement of others and related criminal activities.” Some of the jurors were so outraged they conducted their own investigations, driving around Houston, interviewing witnesses, and trying to find out where more bodies might be buried.

Perhaps the only moment of sanity came during a pretrial hearing for Henley, when his mother, Mary, ran across her neighbor Dorothy Hilligiest. A reporter who witnessed the scene wrote, “Each tried at a choked smile and a politely blurted hello. Formally, they addressed each other by last names.”

Until Mrs. Henley moved to East Texas thirteen years later, she stayed in the same house on Twenty-seventh Street, and whenever Mrs. Hilligiest would see her at the grocery store, the two women would continue to politely say hello. “My mom did her best to forgive,” recalls the Hilligiests’ youngest son, Stanley, who now works for a Houston oil field services company. “But I’ll never forget getting out early one day from high school, and I came home and found her with all the photos and all the newspaper stories spread out. She was screaming, ‘Why, God, why?’”

Years passed before many parents were able to clean out their sons’ rooms, keeping only such souvenirs as a penmanship award, a report card with straight A’s, a layaway receipt for a bicycle, or a crayon drawing of a mother’s smiling face. When friends would come to visit, the parents tried to talk fondly about their sons, but they inevitably ended up saying such things as “If only I had picked him up from school that day” or “If I hadn’t said anything about him needing a haircut” or “If I had just given him one last hug.”

Whenever Henley or Brooks would apply for parole, saying that he was no longer the misguided teenager he had once been, the parents were forced to relive the murders as they wrote letters to the state parole board, detailing the torture their sons had endured. In 1997 they were devastated to learn that a local art gallery would be showing a collection of paintings that Henley had done in prison, ranging from landscapes to a pencil drawing of the model Kate Moss. Some parents and family members stood outside the gallery on opening night, holding signs that read “Hang Henley! Not his art!” Despite the protests, 21 of the 23 paintings quickly sold.

“I know people will always think that I’m evil,” Henley says. “But I know it’s not true. I know I’m not useless. I know I’ve become someone my mom would be proud of.” For a moment, he fiddles with his reading glasses. “Do you realize I hadn’t even gotten my driver’s license, and there I was, out committing murders with Dean just because I wanted to please him?”

Nevertheless, Henley and Brooks do not have to be reminded that their murder spree continues to destroy lives. In 2008 Henley’s onetime buddy Tim Kerley, who survived Corll’s torture board, gave his one and only interview to a Houston television station. “I have two choices,” Kerley said about that night in August 1973. “Either accept it and move on or kill myself.” According to a close relative, Kerley spiraled downward after the interview, drinking heavily and suffering from his own form of post-traumatic shock. In March 2009 Kerley died in South America, reportedly from a heart attack.

Meanwhile, many parents of the murdered boys remain frozen in time, still unable to understand what happened to their sons. Some of the parents are now in nursing homes, their minds starting to slip away. “Which is maybe a blessing, considering all that they’ve suffered,” says Deborah Aguirre, whose mother, Josephine, suffers from Alzheimer’s disease. “Yet when I’ve mentioned my brothers’ names in front of her, she’s started to cry.” Over in southwest Houston, the Garcias—80-year-old Luis and 77-year-old Doris—continue to live in their same home, with a faded photo of Homer on the wall, and on Sundays, they still put on their best clothes and visit his grave, setting down fresh flowers while staring at the words on his marker, which read “The day they took you, part of us went with you.”

And in the Heights, there is Mrs. Scott. In September, when her neighbor Mrs. Hilligiest died in her home at the age of 88, Mrs. Scott told her younger son Jeff, who had moved back in with his mother to look after her, that she could be the last parent left in the neighborhood who had lost a son to Corll. Although she was unable to attend Mrs. Hilligiest’s funeral, held at the same Catholic church in the Heights where David’s had been, she heard that the priest had told the mourners that despite the many good things Mrs. Hilligiest had done over the years, she would always be remembered as “a woman of sorrows.” Mrs. Scott said to Jeff, “There are days when that’s what life feels like, just sorrow.”

Driving past her house on their way to and from work, the new generation of residents barely notice Mrs. Scott as she stands in the front yard, feeding her doves. They have no idea who she is—and why would they? When Sharon Derrick rang her doorbell in October, Mrs. Scott assumed that everyone had forgotten about the murders. “I’m sorry?” she said to Derrick. “You’re here to talk about my Mark?”

As a teenager growing up in Austin, Derrick had read as many newspaper stories as she could find about the killings. But she too had forgotten about them until 2006, when she went to work at the Harris County Institute of Forensic Sciences. One afternoon she walked into one of the institute’s refrigeration units and saw two plastic tubs and a cardboard box, each one marked “1973 Mass Murders.” The containers held the unidentified remains of three boys dug up from Corll’s burial grounds.

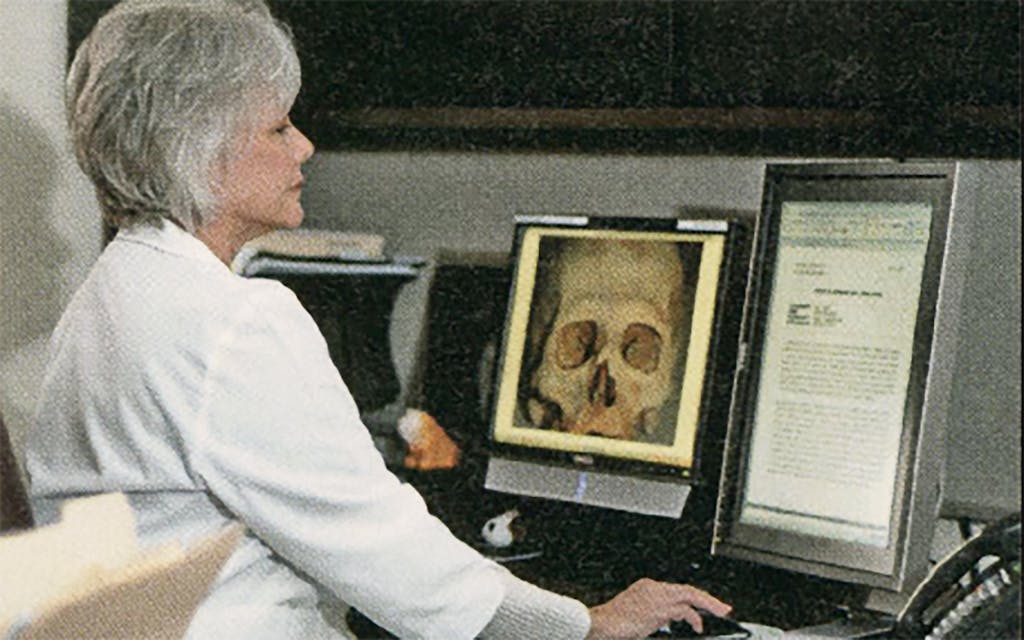

Derrick, a scholarly, silver-haired woman, had no idea there were still bodies from the Corll killings that had never been identified. During her free time, she began studying old autopsy reports. She read the original police case files of the murder investigation, and she tracked down as many of the missing persons reports as she could find that had been filed with the Houston Police Department between 1970 and 1973. She also perused a stack of other missing persons reports, the pages yellowed by time, that had been mailed to the medical examiner’s office in the seventies from parents and police departments around the country (one of Derrick’s colleagues had come across the reports stashed in the back of a file cabinet). Derrick then conducted DNA tests on the unidentified remains—DNA testing wasn’t used to identify bodies in 1973—and she sent the skulls of those remains to a laboratory at Louisiana State University that specialized in computerized facial approximations.

In December 2006 she drove to the Ramsey Unit to meet David Brooks. They sat across a table from each other in an office, and Derrick took a breath. Though he had agreed to meet her, she had no idea if he would cooperate: He had never spoken to anyone other than a few close friends about his role in the murders. But somehow she was able to get him to open up. Discussing his early days with Corll, he said, surprisingly, “I wish I had told my mother what he was doing to me. If I had told her, I wouldn’t be here now.” He mentioned that the girl he had married in July 1973 had given birth to their daughter, who regularly visited him when she got older. But, he told Derrick, his eyes filling with tears, she had died in a car crash on the night of her high school prom.

Derrick slid a photo of one of the computerized facial approximations across the desk and asked if he knew the boy. Brooks stared at the photo and said he didn’t know who the boy was, but he knew how he had died. Then, on a sheet of paper, he drew a map of an intersection in the Heights, Shepherd and Thirteenth Street, and he pointed to a particular corner where the boy had lived. Derrick realized that that was the home of a boy who had disappeared in 1971 and whose frantic mother had filed a missing person report two days later. After she learned that the mother had recently died, she contacted the two sisters of the missing boy. They came to Derrick’s office and began to weep. “I wish Mama had been able to know this,” one of the sisters said. “She would have had some peace when she died.”

After doing DNA tests with a colleague at the institute, she discovered that a body stored in a different area of the refrigeration unit—it had been found on High Island in 1983 and labeled as “archaeological remains”—was actually another Houston boy who had been murdered by Corll, which upped the known number of his victims to 28. She then received an intriguing tip from two Houston freelance writers, Barbara Gibson and Debera Phinney, who publish their stories at texascrimenews.com and are so obsessed with the killings that they’ve approached the owner of Corll’s old storage shed to ask him if they can dig even deeper than the police did. The women told Derrick that they believed that the medical examiner’s office had used the wrong missing person report in 1973 to identify the remains of Michael Baulch, one of the two Baulch brothers who were abducted and murdered on separate dates, and that he could very well have been misidentified. After doing more DNA tests, Derrick realized they were right. Since the parents were both dead, she was forced to call the siblings of the brothers to give them the news.

As stories about Derrick’s work appeared in the local media, more families began contacting her, some from as far away as California and Florida. A family called from North Texas, telling her that their son, hitchhiking to Houston, was last seen in Dallas getting into a white van. (Corll had been known to make trips to Dallas.) Mitzi Piersol, a 39-year-old mother from the Houston suburb of Cypress, told Derrick she was only a year old when her 16-year-old brother, Rodney, disappeared from the English Oaks apartments, located on Gessner near Interstate 10, one of Corll’s old stomping grounds. Her family had an all-too-familiar story. Her grieving father, she said, had gone into rages and blamed himself up until the day he died, and her mother had slipped into a depression from which she still hasn’t recovered.

Derrick became even more driven to help these families. After reading the file on Mark Scott, she especially wanted to do what she could for Mrs. Scott. There had always been questions about what had happened to Mark’s body after he was murdered. In 1973 officials with the medical examiner’s office had told the Scotts that they believed Mark had been buried at High Island but they weren’t sure where his remains were. Desperate to find his son, Walter Scott had driven to High Island almost every day with a shovel so he could dig into the sand and “pray for something to guide me,” he later said. In 1994, more than two decades after the murders, the medical examiner’s office presented the Scotts with remains that they said they believed were Mark’s, based on early versions of DNA identification. Although the family had the remains cremated and placed in the family columbarium at the Chapel of the Chimes at Brookside Memorial Park, they were still not convinced they had been given the right boy.

Fortunately, the medical examiner’s office had kept a single bone from the remains that had been given to the Scotts. When she visited Mrs. Scott and Jeff, Derrick said that because DNA technology was now so advanced, she would be able to let them know if Mark was in their columbarium. All she had to do was get a DNA sample from one of them and compare it with a new sample she had taken from the bone. “I think this might give you some peace of mind,” Derrick said to Mrs. Scott, who nodded and replied, “I would like to know.” Derrick swabbed Jeff’s cheek and returned to her office, where she sent the DNA to a laboratory at the University of North Texas to be processed.

Finally, in February of this year, Derrick received the results. She returned to the Scotts’ home and asked Mrs. Scott and Jeff to sit down. In what she would later describe as one of the saddest moments of her career, she told them that the DNA from Jeff’s swab didn’t match the DNA that came from the bone. The conclusion was inescapable: Mark was somewhere else. Derrick said that his remains were probably still at High Island. She paused and added that because the beach had been under water since Hurricane Ike, there was a good chance Mark would never be found.

Mrs. Scott said nothing. Nearly forty years later, the grief was still so intense, and so bottomless, that she looked as if she could not take another breath. Then she said, “If we’ve got someone’s else son, I want his real family to have him.” For a few seconds, Derrick held Mrs. Scott’s hand. Attempting to console his mother, Jeff told her, “Maybe the ocean will uncover him and someone will find him floating in the water. Or maybe he’ll wash up to shore, and we can give him a proper burial.”

“All I’d like to know, before I die, is where that man put my son,” Mrs. Scott later said. “I want to know where my Mark has gone.”

She walked outside to feed her doves. “I like that they come to see me,” she said, throwing an extra handful of birdseed toward Miss Whitey. “I like knowing that they need me.” For a moment, she started to look down the street. There was a figure in the distance. But then Mrs. Scott stopped herself and spread more birdseed around. The doves around her fluttered, then settled, then fluttered again. When all the birdseed was gone, Mrs. Scott walked back inside her house to sit on her flower-print couch, where a photo of Mark, smiling broadly with dimples in his cheeks, sat nearby.