If you want to experience a real old-fashioned Texas Christmas, make sure you’re equipped with gunpowder, moonshine, and adequate health insurance. For its first century, the state celebrated a holiday that was short on snow, sugarplums, and other Dickensian trimmings. But there was no lack of fireplaces or family togetherness (then known as cabin fever), and dozens of do-it-yourself diversions were readily available in the godforsaken wilderness that was then Texas.

For example, noise. It was cheap and easy to produce, and making it is arguably the state’s oldest holiday tradition. Frederick Law Olmsted, who visited Texas in 1853, described San Augustine’s Christmas Serenade: “A band of pleasant spirits started from the square, blowing tin horns, and beating tin pans, and visited in succession every house in the village, kicking in doors, pulling down fences.” Locals forgave the vandalism; after all, it was Christmas. Later on, the increasing availability of gunpowder made recreational explosions a popular tradition; pranksters of all ages (but a single gender, no doubt) poured it into dead trees or holes in the ground, then lit a fuse and ran.

A particularly dangerous variation on this perilous pastime was the anvil shoot, a tradition that exemplifies natural selection at work. Two anvils were stacked one on top of the other, with a layer of gunpowder in between; then the, uh, bravest participant lit the fuse. The point was not how high the top anvil flew but how loud the roar was; with luck, it carried glad tidings to neighbors miles away. Eventually, mass-produced fireworks made the requisite holiday clamor easier to achieve but no less risky. In her 1894 memoir of ranch life near Junction, Mary J. Jaques observed that “the fame of our Roman candles, rockets, and fire-balloons spread in due course as far as San Antonio. But after the display . . . we discovered that the roof of the gallery was on fire.”

One factor that allowed outdoor pyrotechnics to become a Texas Christmas tradition was the weather. Although the Panhandle, for example, regularly endured killer blizzards, most of the state was mild, even hot, on Christmas Day. In 1867, according to a San Antonio paper, “the weather was too warm and the eggnogs were spoiled.” In “Star of Hope,” a Yuletide story set in thirties Houston, William Goyen noted that “the sun blazed down and electric fans were on.” Historian Joe B. Frantz, born in Dallas in 1917, wrote, “I never saw a white Christmas until I was 58 years old, and that was in Munich, Germany.”

Sometimes the holiday noise was joyful. The first Noel in these parts was observed, probably with prayer and hymns, as early as 1528, when Spanish explorer Cabeza de Vaca and three of his men were holding body and soul together on the Texas coast (near what is now called, ironically enough, Christmas Bay). In 1686 his French equivalent, LaSalle, spent the day in the same region. San Antonio’s San Fernando Cathedral has celebrated Christmas Eve mass since the 1730’s. What is now termed an interfaith service was once standard practice: In 1852 a young Catholic priest named Emmanuel Domenech wrote that he had conducted a Brownsville service for “a crowd of every age, sex, and creed.” But Protestant churches sprang up quickly; on December 25, 1858, eight men and women in a Matagorda schoolroom were the first Episcopalians in the nation to take Holy Communion.

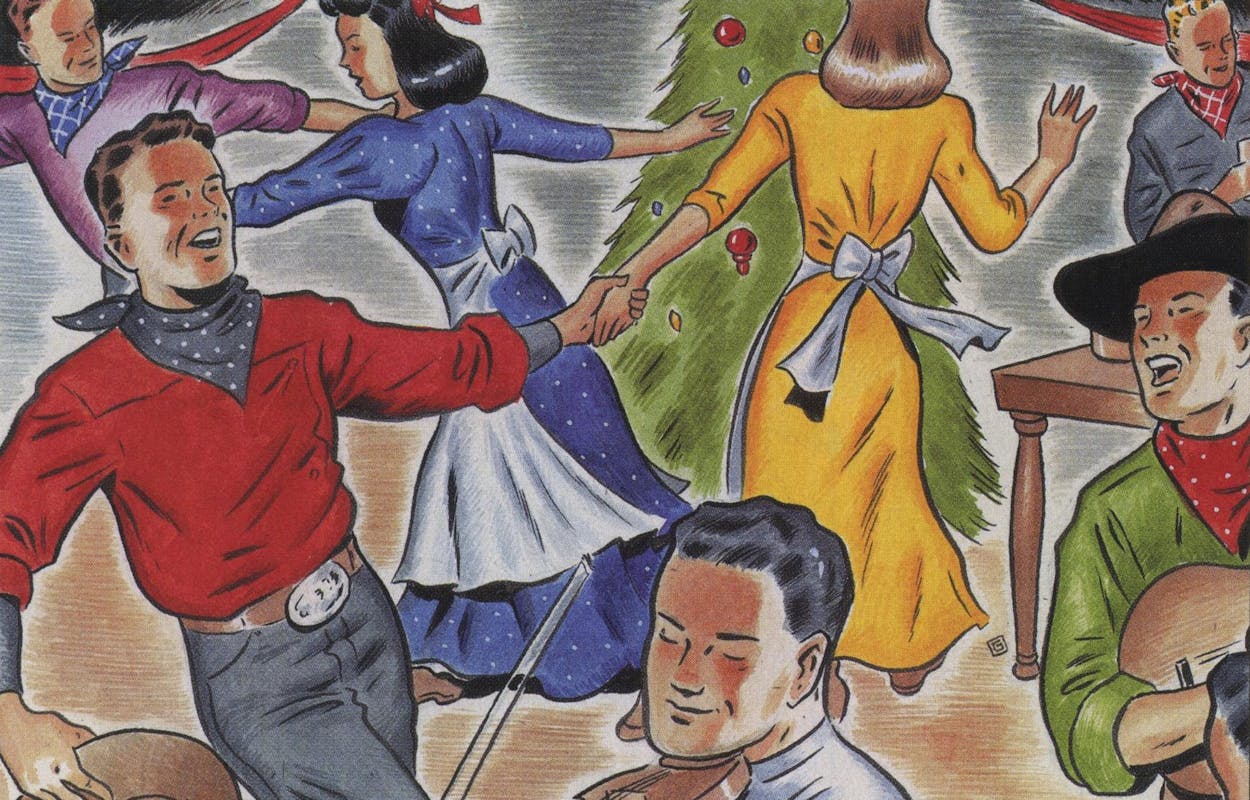

Natives and immigrants of all ethnicities enjoyed that enduring classic, the Christmas party, especially if someone was fortunate enough to own a musical instrument. Such pioneer virtuosos were the linchpins of yesteryear’s social gatherings, though the truly essential element, at least until the twentieth century, was female dance partners. In 1882 Lizzie Campbell, the mistress of the Matador Ranch, enlisted the help of the resident cook, who “scraped his fiddle” at her annual Christmas bash. She invited some fifty cowboys; then, having a warm heart—and a strong sense of self-preservation—she also arranged for five other women to attend, the closest of whom lived seventy miles away. The merrymakers “tripped the light fantastic for long and weary hours,” one chronicler noted. A particularly famous shebang was the one in Anson, which in 1885 inspired New York Times reporter Larry Chittenden to immortalize the event in his poem “The Cowboys’ Christmas Ball.”

Of course, the town of Anson was in wild West Texas. In the 1880’s, sophisticated Galveston saw many a ritzy affair breathlessly detailed in society columns (“Mrs. Short Willis [wore] brown velvet, pink roses and diamond ornaments”), and San Antonio’s elegant Menger Hotel served a Christmas repast that included Benwick Bay oysters, baked filet of trout au gratin, and prime beef with Yorkshire pudding. But regular ol’ Texans feasted on game, simply because there wasn’t much else around (“vegetarian” was a swear word back then). Jack Elgin, traveling with surveyors in West Texas in 1872, stuffed himself at a Christmas dinner: “We had buffalo, antelope, deer, bear, rabbit, prairie-dog, possum, and possibly other animals that I do not recall; turkey, goose, brant, ducks, prairie-chicken, curlew, quail, and other birds.” (He added that “one of our hunters offered to furnish us with a mess of rattlesnakes and polecats, which he assured us were a most excellent delicacy, but our cook drew the line at these.”) Novelist Elithe Hamilton Kirkland, who was born in Coleman in 1907, celebrated less carnivorous Christmases, enjoying “once-a-year fruit and nut treats” such as apples, oranges, bananas, walnuts, and coconuts. Texas fruitcake bakers traditionally substituted watermelon-rind pickles for genuine citron, and they sorely missed fresh eggs and milk; one West Texas wife lamented that her only ingredient for a holiday cake was “sheer sweet ozone.”

Eggs and milk were also necessary for making the ultimate Christmas beverage, eggnog. But to Texans they weren’t as essential as whiskey, which a German visitor characterized in 1845 as “the national drink here with which Christmas is celebrated.” The so-called “white mule” was fiery and raw, distressing an English traveler who complained around Christmas, 1839, that it made for eggnog “of a very bilious nature.” Soldiers were especially famous for cutting loose at Christmas: H. H. McConnell, on duty at Fort Belknap and Fort Richardson in the 1860’s, despaired of the “thousand and one ways and means that a soldier will indulge in to get whiskey.”

Except for pink elephants, there weren’t that many colorful Christmas ornaments way back when. German immigrants—shocked that the primitive Texans had never heard of a Christmas tree—introduced the tradition to the republic, and in a few decades trimming a tree became de rigueur. In 1882 the Austin Statesman advised, “Christmas trees are now in order. If you cannot pay two dollars for one, take a hatchet, go out in the wood, and poach on somebody’s forest.” This was standard practice; even as late as 1947 the Texas Forest Service offered tips for harvesting the state’s “unlimited supplies” of “evergreen ropings” and “berried branches.” In some areas, a tree was much harder to come by; in 1890 a Wellington ranch wife recalled having to settle for “a miserable little stunted cedar.” Since shiny glass globes and other mass-produced ornaments were nowhere to be found, she adorned her scrubby tree with bits of leftover calico and tinsel made from foil peeled off chewing-tobacco pouches. Eventually Texans would borrow many Mexican holiday traditions, such as piñatas (the traditional starlike shape was a particularly fitting choice for a Texas Christmas) and luminarias, the sand-filled paper bags that hold lighted candles and are used to line walkways and porches. Mexico also gave us the poinsettia, a.k.a. la flor de nochebuena, or “the Christmas Eve flower,” and edibles like tamales and sweet, cinnamony buñuelos.

Then there was the problem of presents in the past. Pioneer kids usually found in their stockings homemade gifts such as rag dolls or hand-carved tops. Evelyn Miller Crowell, who grew up near Dallas, recorded in her memoirs that in 1904, when she was five, her presents from Santa included a doll, a miniature stove with pots and dishes, a beaded purse, and “books and books and books!” In 1865, when Major General George Custer was stationed in Austin, he gave his younger brother Tom a Jew’s harp with a note to “give the piano a rest.” Even as stores became bigger and better supplied, by today’s standards the choice of goods was limited; novelist Benjamin Capps recalled that for Christmas, 1929, when he was seven, he gave his mother a new spatula. Some gifts were even more memorable; on December 25, 1907, in the hamlet of Voth, a young couple was blessed with a baby boy, Glenn Herbert McCarthy, who forty years later was a rich and famously flashy wildcatter. And no real-life Santa was ever more generous than Fort Worth’s Tom Waggoner, who on Christmas Day, 1909, divided up half of his million-acre ranch among his three children.

Miscellaneous entertainments rounded out the holidays—blowing up hog-bladder balloons, for instance, or chasing livestock down Main Street. You had to do something special: “We all shaved and ‘greased up’ with bear-oil for Christmas,” one of a party of bachelor cowboys noted ruefully in the late nineteenth century, “the only thing we could think of doing.” Ranch hands frequently imitated medieval knights and put on rodeo-style tournaments; amateur talent shows were also popular, the more highfalutin the better. Florence Fenley, of Uvalde, participated in carolfests and literary soirees in the 1880’s: “We were just as liable to spring Tennyson on them as some lesser poet, and if the audience didn’t understand or hear a word, they applauded heartily.”

Having fun, especially at holidays, is a Texas specialty. A determination to make the best of everything, come what may, is one tradition well worth preserving. In 1909 an East Texas man recalled a particularly unpromising holiday of his childhood: “A merry Christmas in the dark and dreary days of 1864 seemed almost impossible in Texas, where the pangs of war were so keenly felt . . . but we had always observed Christmas in the family and could not abandon a time-honored custom. . . . Yes, we were going to have a merry Christmas in spite of the unpropitious surroundings.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Hunting