All gamblers live at night and the two men riding in a Winnebago from Austin to Houston thought this night would be a long one. They were going to a pool hall named Goofey’s where there was usually action, enough action to warrant driving 160 miles.

The two men were not only friends but also a business partnership of a kind long recognized in pool halls across the country. Terry, who owned the Winnebago, was a stakehorse, a financial backer. He was a short, round, rather wistful-looking man, about 35 or 40, whose baggy work pants and cheap short-sleeved shirt camouflaged the large roll of cash he carried in his pockets. Terry’s money came from a successful family business, but his real passion was gambling. He liked cards, he liked dice, and he liked pool. Not a particularly good pool shooter himself, Terry got action by staking others. For the past two years he had been staking a player named Roger who was riding with him now to Houston. The terms of their partnership were the traditional ones between a hustler and his stakehorse: Terry absorbed any losses; Terry and Roger split any winnings fifty-fifty.

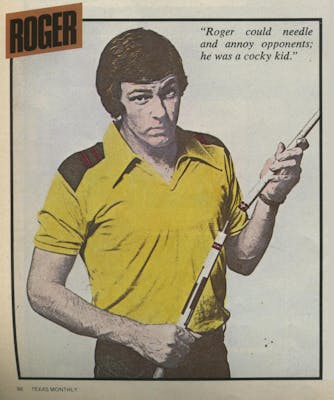

Although Roger seemed satisfied enough playing for Terry for the present, he was uncertain about the future. He knew he wanted to win at Goofey’s, and if a hustler named Richie Ambrose should be there, as he usually was, Roger especially wanted to beat him. But Roger wasn’t certain he wanted to lead the life pool offered. He was barely twenty-one, tall and strong, with the kind of build high school coaches look for in an end and pro coaches look for in a quarterback. He had light brown hair that he kept neatly trimmed and a clean-cut appearance that seemed out of keeping with his savvy and skill in a pool hall. His parents still held considerable influence over him, and several times since he had begun playing pool in junior high Roger had given up the game entirely. Even now he held a regular job at a real-estate agency and intended to get his broker’s license. This was the kind of job his parents wanted him to have, a respectable job with a decent future.

In pool, Roger realized, the future was, to say the least, extremely limited. Pool is such a difficult game that playing it well demands the total commitment of a player’s time, energy, and thought. There would be no room for another job. Also, finding opponents with money to bet requires considerable traveling, and winning that money takes long nights of play, mostly in poolroom dives. As a result professional pool players are usually solitary men who live on the road, know nothing but pool, are frequently broke, and rarely hold onto their winnings for very long. Because he had yet to make that commitment, Roger, good as he was, was not a player of the first rank. If he played Ambrose, who was not the best in the country but certainly among the best fifteen or twenty, Roger would need a handicap to make the match fair. But one thing was clear: that final commitment was the only quality he lacked to be among the best. Roger had the courage, the nerve, and the confidence it took to play for money. He was cocky and brash and complained like an adolescent when things went against him. He could needle and annoy his opponents, which frequently worked to his advantage, and his cockiness made him difficult to intimidate. But in the end what all this brashness and cockiness and young man’s pride amounted to was this: Roger liked to act like a champion but he was not quite a champion yet.

When they pulled up to Goofey’s on the near-west side of Houston, it was about 9 p.m. The place is dominated by 25 pool tables that run down the middle in neat rows. Along the walls are pinball machines, a long, curved bar, and a glassed-in shop selling gaudy trinkets, cigarette lighters, and tacky jewelry. The clientele tend to stand around the tables in premeditated and self-conscious postures, some wearing flashy slacks and sporting thin silver chains around their necks, while others favor grimy T-shirts, heavy boots, and sweat-stained cowboy hats over long, tangled hair. Although there are many more men, there are women, too, especially on weekends; few look over twenty. They wear thin jerseys and tight blue jeans. Some go barefoot and the rest wear platform shoes. They watch their boyfriends play or play tense games among themselves or stand along the sides looking at nothing in particular. The fluorescent light shining through the smoke from countless cigarettes creates a haze from one end of the hall to the other. A jukebox, turned up very loud, plays an endless string of disco hits.

At the end of the bar is a small alcove just big enough to hold two tables. Table time here costs twice as much as in the main room. These tables are normally available for big-money games. Ambrose, as they had expected, was standing near those tables. “Come on,” Terry said. “Let’s match up.”

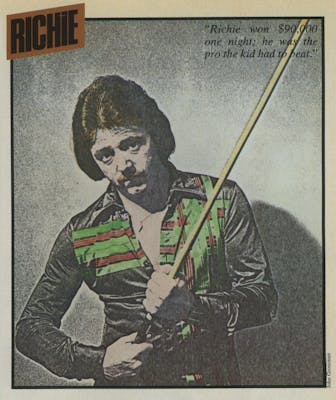

Richie Ambrose was forty years old, but his pride was that people never took him for more than thirty. He had a black moustache and long, black hair parted in the center. Of average height, he had a stocky build with thick arms, one of them tattooed, and liked to dress in black or white jeans and brightly colored shirts printed in art deco patterns. He had grown up in New York, and his rapid-fire speech was still loaded with a heavy Eastern accent, but he had come to Houston two years earlier to play in a tournament and stayed on because he thought the town had possibilities. “Forget the East,” he liked to say. “The East is dead, you know what I mean? West. Everything is West now. All the money, all the energy, everything is West.” He lived in a modest but comfortable apartment and divided his time between playing in tournaments across the country, gambling in Las Vegas, and hustling in Goofey’s. Unfortunately, he was by now so well known in Goofey’s he usually had to give an opponent a big handicap. “I’ve got to give away too much weight” was how he put it. In a way, it was time to move on, find another place where he wasn’t so well known. But at forty, life on the road wasn’t so appealing as when he was younger, nor was he shooting as well as he once had. There was a time, beginning about 1969, when he thought he was the best player in the world at his best game, nine ball. On a night in 1971 that has become legendary among those who follow pool, he won $90,000 in Detroit. Much of the money went to his backers, but with his share he opened a room in Detroit and named it Mr. Nine Ball. On his street sign and at the bottom of his ad in the Yellow Pages he threw out a broad challenge: “You can get played.” Now he was just one of the best, not the best, and there were young players coming up, like the kid Roger, who were getting harder to beat every time. Richie needed another source of income. And he had an idea, one he was sure would work in Houston.

Richie had grown up with pool. His father had once owned a room in New York. Like most top players, he was good almost from the moment he picked up a cue. He could run thirty straight balls after he’d been playing for three months. He was soon able to beat anyone who played at his father’s room and brashly began going across town to a room that was the home ground of Jersey Red, Boston Shorty, and other great hustlers of the day. When he could play them even and win, he began hustling around New York. He knew that if he was in a league with Red and Shorty and their peers he could beat anyone else in the world. In 1956, at nineteen, he won $5000 in twelve days. Scores like that inured him to his mother’s nagging that he was turning into a bum. Some bum, he thought. He knew he was making more at pool than his mother, father, and brother combined made at their jobs. He left home and went on the road.

“Pool is the hardest hustle there is,” he says now. “There’s driving. All that driving about kills you. Then you have to play all night long. Your back hurts, your feet hurt, and maybe you play eight or ten hours and lose. You had to give up too much weight. No money for all that time. Now you’ve really got to work. Lots of times I’ve been playing for fifty dollars and had two dollars in my pocket. Playing on nerve, you know what I mean? But it’s fun too. How else am I going to get to travel like that? Meet all the people I’ve met? And you know, take my mother. She worked all her life at some nothing job and what’s she got? A little apartment and a couple hundred bucks saved in the bank. Well, that’s what I’ve got. I’ve got a little apartment. I’ve got a couple hundred bucks in the bank. But I’ve never worked.”

Although hustling pool is sometimes dangerous work, Richie says he’s never had any trouble playing on the road. “I’d just walk into a place and say, ‘Anybody want to play nine ball?’ Nine ball’s a hustler’s game, so right there I was giving myself away, you know what I mean? You feel kind of like a gunslinger coming into town. And every little town has its champion and everyone runs around trying to get him matched up with you. The out-of-town guns against the local guns.”

But at forty, an athlete with great natural ability and twenty years’ experience, a man who never smoked, seldom drank, and stayed away from drugs to maintain his physical condition, Richie Ambrose had little to show for his life. Like other top players his age or younger, he had seen the boom in prize money offered to golf and tennis pros during the last ten years, and he was convinced that pool, properly organized, would inspire enough public interest to create a similar bonanza. The creation of a pool tour, similar to the golf or tennis tour, with large cash prizes and the public interest and recognition that would follow was one of his two great hopes for the future. “I’m as good at my game as the golfers are at theirs,” he sometimes grumbled. “I want to get some recognition for what I do.”

His second great hope was to open his own room in Houston. He had had to give up his room in Detroit for reasons that he thought were really beyond his control. “When I was hustling I never had any headaches,” he said, “but as soon as I got a room, when I was going to become a legitimate taxpaying businessman, all of a sudden I’ve got nothing but headaches. Cops coming around. City inspectors. The people in the neighborhood—it was kind of a nice neighborhood, really—were all against me because they thought I was letting kids hang out in there. So I tried to fight. So what if kids come in, you know what I mean? They can go into movie theaters, they can go into drugstores, why can’t they come into a pool hall? Anyway, finally it got too much and I got tired of all the headaches.” But the place he wanted in Houston would be different. “I’m not talking about some dump,” he said. “I’m talking about a nice place with nice tables. And, off to the side, a bar, but nice, you know what I mean? Nice with good decoration. And maybe in another part, who knows, maybe a disco. I mean, why not? With a place like that in this town you’d make nothing but money. It’s perfect.”

Richie figured he could get the $40,000 he needed to start his room by gambling, not gambling at pool but at craps in Las Vegas. He would make $300 to $500 hustling pool, then catch a plane to Vegas to parlay his small winnings into big money. “What’s five hundred bucks to me?” he said. “Nothing. It gets me nothing. You can’t start a place with five hundred dollars. All it does is give me a chance at that forty thousand. If I lose, I lose nothing. If I win, well, then I win, you know what I mean?”

But the Friday when Roger and Terry walked into Goofey’s, Richie was a little short. He had a plane ticket to Vegas on Monday, but it wouldn’t be worth going unless he could hustle some more cash. And there, as if sent specially for him, were Roger with his cue stick in a flashy white leather case and Terry with his roll of cash hidden in his pocket.

It didn’t take them long to match up. Richie would give Roger no more than a two-ball handicap. Terry, who had to put up the money, was somewhat dubious about Roger’s chances with only a two-ball spot, but he agreed anyway. It would be good experience for his player. They agreed to play three ahead for $50; the first player to establish a three-game lead would take the money.

They picked up a set of balls and walked over to one of the tables in the alcove. They took out nine balls, and put them on the table. Richie took off his black and gray shirt. Underneath he was wearing a black sleeveless undershirt. His arms and shoulders were white and fleshy. The bright row of lights above the table made his tattoo stand out.

Roger took off his boots and threw them under the table. He liked to play in his stocking feet. As they stood screwing together their cues, they eyed each other across the table. Roger, there with his backer, was a cocky kid. Richie, with his black hair and black moustache, was the experienced pro the kid had to beat. Neither liked the other very much. Neither was going to give the other a chance.

Poolrooms have had bad reputations from their first moment in history, probably four to five hundred years ago. By 1591 the game was well enough established in England for Edmund Spenser to complain about its lure in a poem. But Spenser’s complaint was that billiards, until this century the generic term for all games that involved pushing balls around a table with a stick, was absorbing too much of the aristocracy’s time. In Spenser’s day and for centuries after, no noble manor was complete without a billiard room, and to this day the term billiards suggests a kind of wealth, breeding, and social position that is completely at odds with the rather common, dingy, and thoroughly American connotations of the word “pool.” Yet the game had a schizophrenic identity in England well before it was imported to America. A noble’s billiard room was one thing: a public billiard room was another.

Of course there is a game named billiards that is distinct from what we now call pool. Billiards is played with three balls on a table without pockets. The player scores points by making his cue ball strike the other two balls. This seemingly simple game, extremely difficult to play well and almost impossible to play at all without considerable practice, is by now so nearly forgotten in America that its former popularity, which lasted until the beginning of World War II, is hard to believe. Old photographs of the famous rooms of the twenties and thirties show row upon row of billiard tables running down the center, while the much smaller number of pool tables are tucked away in the corners.

But pool was popular, too. Ralph Greenleaf, the great champion of the day and with the possible exception of Willie Mosconi the greatest player who ever lived, gave exhibitions in major theaters at a fee of $2000 a week. Nevertheless, pool had a reputation as a rather unsavory cousin of billiards. As early as 1904 the Brunswick Corporation of Chicago, even then the largest manufacturer of pool and billiard tables and supplies, was involved in a losing battle to dignify pool. It carried an editorial in its catalog that year pleading that pool be referred to as “pocket billiards” since the term “poolroom” was more often applied in those days to what we would now call a bookie joint.

And with poolrooms came hustlers. Traditionally theirs is a somewhat anonymous world. Some of the greatest hustlers shun photographs and avoid organized tournaments so that marks won’t recognize them. At the same time hustlers have always felt a need to match up against each other. Sometimes other hustlers are the only ones with money to bet, but other times, although there is always money at stake in these games, the contest is basically to prove which player is better. Consequently all hustlers know, or know of, all the prominent hustlers; and in any major city, even if a hustler has never been there before, he will know which are the rooms with action and the names and relative skill of various local players. This information is so essential to a hustler’s business, and the pool grapevine is so well established, that there would be nothing unusual about hearing a conversation in a San Francisco poolroom about a match that was played in a Miami room just the night before.

Hustlers traditionally carry Runyonesque nicknames that are not only quaint but also have a practical purpose. Even so relatively obscure a player as Dennis McMahon, who is the San Antonio city champion but has seldom played outside Central Texas, is known as Tall Dennis to a wide circle of players both in and outside the state. Players who remember that name would soon recognize him inside a San Antonio room even if they had never seen him before. In addition to the previously mentioned Jersey Red and Boston Shorty and the well-known Minnesota Fats, the annals of recent pool history also contain the names of such prominent hustlers as Sleepy Bob, a Californian who gave up playing when he got religion; Tippy Toes Joe; Rags Fitzpatrick; Bananas Rodriguez, who spent forty years as a road player and now runs Ye Olde Billiard Parlor in San Antonio; Woody Woodpecker; Cornbread Red; Baby Face Witlow, whose ex-wife is also a top player; St. Louie Louie; Cannonball and Tallahassee, two great black hustlers; Deputy Dog; Wimpy Lassiter; the Knoxville Bear, a superior hustler renowned as a hard drinker; Weenie Beanie; Handsome Danny Jones, who now lives in Houston but grew up in a small Georgia town near Plains; Tugboat Whalen; Detroit Whitey; Toupee Jay, who wears a toupee as a disguise; Peter Rabbit; Captain Hook; and Fast Eddy; as well as some unnicknamed hustlers like Richie Florence, Jimmy Rempe, Danny DiLiberto, and from Fort Worth, Utley Puckett.

Born just a few years this side of the turn of the century, Puckett is a hustler in the classic style. Always in command of an endless line of stories, chatter, opinions, and advice (a tournament program once noted that “half the game he talks would be sufficient to win the tournament”), Puckett spent years traveling around the country wearing a Texaco uniform so he could pass as a filling station attendant. He would also wear a hunting outfit from Abercrombie and Fitch, in keeping with which he would try to replace his broad Texas inflections with a British accent. Once in Lubbock, disguised as a farmer, he had matched up a game only to discover that he had no money to stake. He muttered something about having to see about his wife and set out into the town where he knew no one. By the time he returned to the poolroom, he had convinced a total stranger to loan him the money he needed. He made one of his biggest scores when a man he was beating at pool suddenly threw down his cue stick and challenged him to Ping-Pong. “I don’t think I can beat you,” Puckett said, “but my little brother can.” Puckett then flew to New York where he knew a young city champion, “rented” him from his parents, and returned to his mark with his dearly beloved brother in tow. The mark went broke trying to beat the kid.

Puckett is a tall man with a thick chest and wide shoulders. He has long white hair and even at his age still has the grinning, priapic look of a satyr. He has honed his style so well over the years that he can look you right in the eye, all friendship and easy familiarity, lie to you so that you know that he’s lying, yet still take you in. Even many other hustlers agree that few men have understood hustling as well as Puckett. “Just shooting balls doesn’t cut it,” he says. “You got to talk. It’s not a good score if you win a thousand and everybody’s mad at you. But if you win a thousand and everybody likes you, hey now, then that’s doing it right.” He accomplishes this dual feat by a method so extreme it is virtually unheard of: “I always tell the truth. I walk into a poolroom and I say I’m a pool hustler and that I’m just camouflaged as a hunter. They never believe me anyway. And then if there’s an argument I just say, ‘Well, hell, I told you I was champion of Texas and I wasn’t bullshitting.’ Really I do. And there’s always somebody around who’ll stick up for you, you know, say, ‘Hell, that’s right. That’s exactly what he said.’ ”

He attributes his long success as a hustler to one personal quality: “I’m not greedy. Really, I’m not. I can do everything in the world better than everybody else except make money. But that’s the way I want it, really it is. You can’t like money and be a gambler. You will definitely be unhappy.”

While Puckett’s point may reflect a certain hard-won wisdom, most younger hustlers do love money, or they like it well enough at least to wish that their skills would bring them more. They are, like Richie Ambrose, hoping for the establishment of a national tour with big prize money and a television tie-in. But there are several problems. Foremost is pool’s reputation. New poolrooms spring up, but few have the elegance of, say, Jimmy Lukacs’ Gordo’s in Austin and fewer still manage, as Gordo’s has, to keep that elegance from rapidly deteriorating. Also, instead of there being one national pool organization, there are three: the old Billiard Congress of America, a rather sluggish organization that is financed by manufacturers; the Professional Pool Players Association, a newer organization of Eastern renegades from the Congress who sponsored their own national championship this year; and the World Nine Ball Association, of which Ambrose is one of sixteen invited members. There are bitter rivalries among the three groups and there is not even a consensus about which game should be pushed. Traditionalists promote straight pool, in which every shot must be called and each ball sunk counts one point. It has always been the championship game in tournaments but is as slow moving to watch as chess and particularly unsuited for television. Others, especially Richie and the rest of the World Nine Ball Association, favor nine ball. It is the most exciting and dramatic game in pool and also short in duration, which makes it perfect for television. And there is a growing movement to push eight ball, not so much for its inherent qualities, but because it is by far the most common game in bars and poolrooms across the country.

It’s not surprising that pool professionals, so used to tight, bitter matches among themselves, should have trouble organizing to decide how to proceed as a group. For, as Puckett came very close to saying, the essential quality that separates a hustler from other players is his attitude toward money. He wants to win it and he wants to win all he can. He must be hard and competitive enough that no sudden wave of sympathy for a losing mark will affect his game. The least little softness in this regard is a weakness that transforms him instantly from a hustler to a sucker, and eventually, during some long night of play, someone else will discover that weakness and rip it open. He must also be courageous enough to risk his own money, all of it, without becoming overly cautious and playing scared. Although requiring all that, hustling offers not a great amount of money, poor working conditions, indifference if not contempt from the world at large, and a rootless life that will seldom come to anything. So why do hustlers do it? Mostly because they know they can and others can’t. It is very hard for anyone to deny his obvious gifts, and knowing that one has the skill and the courage and even the grim lack of pity that hustling requires—knowing that becomes a siren’s song. Richie had heard it twenty-five years ago and now the kid Roger was hearing it, too.

Richie and Roger played for about four hours. They ran through rack after rack, keeping score with three pennies beneath the rail. In nine ball only the first nine numbered balls are used. The player who sinks the nine ball wins, but the cue ball must always strike the lowest-numbered ball on the table before hitting any other ball. Although the nine ball may be sunk in a combination shot after the cue ball strikes the lowest-numbered ball, except in extraordinary circumstances the best players proceed by sinking balls one by one in proper numerical order. Roger’s two-ball handicap meant that he could win by sinking the seven ball while Richie could win only by sinking the nine.

This handicap matched them so closely that they needed to play ten, fifteen, even twenty games before one player pulled three ahead. The remarkable thing about their play was that they did not miss. Sometimes the position of the balls made sinking one so improbable that the shooter would try not to pocket a ball, but to leave the cue ball in a position that would present an equally difficult shot to his opponent. But on the shots that were intended to sink something, Roger and Richie did not miss five balls between them in their four hours of constant play. Halfway through, Richie tried a long shot down the length of the table and into a corner pocket. The ball bounced back and forth in the mouth of the pocket but did not fall in. “That shot was going to win for me,” he said.

“But you missed it, didn’t you,” Roger said, pushing him aside to get into position to shoot.

Generally, however, they didn’t say much to each other, but they were often in physical contact. One would hover around the table while the other shot, and neither one, in eagerness to take the shot and not wanting the other to control the tempo of the game by standing in the way too long, felt any compunction about firmly shouldering his opponent to the side when it was his turn.

Amateurs, before beginning play, often cover their hands with talc so the cue will slide easily through their fingers. But neither Richie nor Roger used any. Not only were the shafts of their cues sanded so smooth that talc was unnecessary but also the need for talc meant a player’s hands were sweaty, and sweaty hands meant the player was nervous. Going for talc was a visible sign of a psychological retreat neither player could afford.

For long periods they would play almost even, but eventually Roger would falter, and Richie, except for the one missed shot in the corner, never did. His stroke always had the same fluid precision. He made no strategic mistakes. Roger did—not many, but enough to make the difference. Once, confronted with a difficult shot, he played safe, leaving Richie with the identical shot. Richie stepped to the table and without the least hesitation made the shot and ran the rest of the table to win the game. When Roger later decided, at a crucial point in the final session, to try a difficult shot rather than play it safe, he missed and Richie ran the table again. Roger lost four hard-fought sessions in a row. Terry, now $200 in the hole, took the loser’s prerogative and threw in the towel.

It is customary for the winner to pay the table time. Richie gleefully picked up the balls, put his black and gray shirt back on, and walked over to the counter. Roger sat in a chair next to Terry and dejectedly pulled on his boots. He looked at Terry and shrugged. “I thought I could beat him,” he said, as a sort of apology.

“You can’t hardly beat a guy like that,” Terry said. “Not unless you play just perfect, even with that two-ball spot. And you’re not going to play perfect the first time you go up against him. He’s played too much. He knows too much. We’ll try him again. He’s not going anywhere. Why don’t you go ask Dan over there if he wants to match up.”

Roger went over to a tall, skinny man in a loose white shirt. He was a little drunk and he demanded a larger spot than Roger was willing to give. Their negotiations broke down very quickly and they stood only two feet apart, arms folded and leaning against a table, and stared darkly in opposite directions. Roger glumly watched Richie talking happily with some cronies across the room.

Richie took the $200 to Las Vegas but he did not win what he needed to open his room. Two weeks later Terry and Roger returned to Goofey’s and played Richie again. The stakes and the handicap were the same and the match lasted about the same length of time. When it was over, Roger and Richie had tied.