“It’s like the Vatican,” remarked my well-traveled teenage daughter as we eyed the line stretching down West Fifty-third Street from New York’s Museum of Modern Art, an onslaught of sweaty pilgrims undeterred by the shopping-mall stampede or the $20 admission fee. And it wasn’t just us out-of-towners who were struck by the crush of humanity at modernism’s most sacred shrine. “Have you seen the ticket lines lately?” a New York Times art critic incredulously queried his readers not long after our July visit, marveling at MoMA’s flip-flop-shod “armies” of visitors.

The army of the faithful at MoMA, however, is just one small piece of an entirely unexpected cultural revival—if not revolution—that is going on in places as diverse as Fort Worth, Dubai, and Shanghai. Modernism, the twentieth century’s tradition-flaunting vanguard culture, was widely considered history well before the beginning of this century, a little-lamented victim of its own rarified aesthetics and overweening ambitions. And with the current zeitgeist all about clashing civilizations and the revival of religious fundamentalism in both the West and the Middle East, we couldn’t have a more unlikely moment for the resurrection of modernism’s liberal, secular humanist, one-world vision. But it’s not just that modernism is miraculously back from the dead: Last century’s avant-garde is starting to look like the surprise winner in this century’s culture wars.

The aesthetics that once offended so many are now transcending our growing divisions over politics and class. At the high end, the mushrooming global plutocracy has made modernism the house style, with works by living masters like Jasper Johns and Port Arthur expatriate Robert Rauschenberg now well into eight figures. Deceased moderns can add another zero; last year an iconic 1948 drip painting by American Abstract Expressionist Jackson Pollock was sold for $140 million to an anonymous buyer, rumored to be a London-based Mexican financier.

But these days the Bauhaus is in everybody’s house, with budget retailers like IKEA and Target basing their booming brands on sleek modernity, while less-fashion-forward discounters like Wal-Mart have seen their stock prices struggle. The signature product of this decade, Apple’s iPod, owes more of its cachet to an elegant, less-is-more design than to superior technology. Mid-century modern, the spare, cool interior style typified by Eames chairs and Barcelona loungers, has achieved near ubiquity among this century’s urban hipsters. This summer’s buzz read, Loving Frank, is a fictionalization of pioneer modern architect Frank Lloyd Wright’s scandalous affair with a client’s wife.

Wright’s followers, however, have emerged as the new millennium’s real culture heroes, a band of modernists who roam the globe branding entire cities with their designer labels, remaking the face of a metropolis with all the brio that Picasso brought to a portrait of a mistress. In their wake a whole generation of history-mining postmodern architects, who spent the final quarter of the previous century recycling everything from Gothic cathedrals to the old Las Vegas strip, no longer appear fashionably retro; now they’re just retro. Today, when Kansas City or Kazakhstan wants to be taken seriously, suddenly everything modern is new again.

Texas has been ahead of this trend long enough to boast some of its seminal monuments. Italian master Renzo Piano presaged “revisionist” modernism way back in 1987 with his louver-roofed Menil Collection, in Houston. The Zen-like, cast-concrete minimalism of Japanese superstar Tadao Ando’s effusively praised 2002 Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth (the nation’s second-largest modern art museum) has set the bar for this century’s best buildings. But for Texas-scale ambition and sheer urgency, nothing matches the modern makeover currently under way in Dallas—nothing, that is, on this side of the international date line.

Beijing and Dallas could hardly seem less alike: the former a two-thousand-year-old imperial city at the center of the last great communist empire, primping madly for its star turn as host of next year’s Olympics, the latter an entrepreneurial upstart less than two hundred years old, trying to outshine its suburbs. But when it comes to civic cosmetic surgery, this urban odd couple is eerily in sync. Among their shared tastes is Sir Norman Foster, the British architect who has almost single-handedly thrust London’s skyline into the future with a fantastic array of high-tech inventions. Currently updating Beijing’s airport (the vast new terminals look like ultrastealthy alien spacecraft), Foster is scheduled to transform downtown Dallas in 2009, when his science-fictional, drum-shaped red opera house will become the bravura centerpiece of the city’s Arts District. Rem Koolhaas, the Dutchman who has designed Dallas a trendsettingly transparent, cubic theater right next door to Foster’s opera house, is also finishing up Beijing’s seventy-story China Central Television headquarters, a huge complex of glass and steel shaped somewhat like a giant akimbo picture frame.

Then there’s Beijing’s rad new Olympic stadium, an undulating, biomorphic bowl covered with a bird’s nest—like exoskeleton of exposed girders, by the Swiss duo Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, considered by many the hottest architects on the planet. The Dallas Cowboys stadium in suburban Arlington, scheduled to open in 2009, doesn’t boast an architect in Herzog and de Meuron’s league, but its stunningly modern design, with vast glass curtain walls and huge steel truss arches, will be a revelation for the National Football League. And Dallas will further narrow the modernism gap with Beijing when it finishes at least one bridge by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava, whose futuristic fractal constructions are as coveted in America’s heartland as they are in Venice, Valencia, or Qatar.

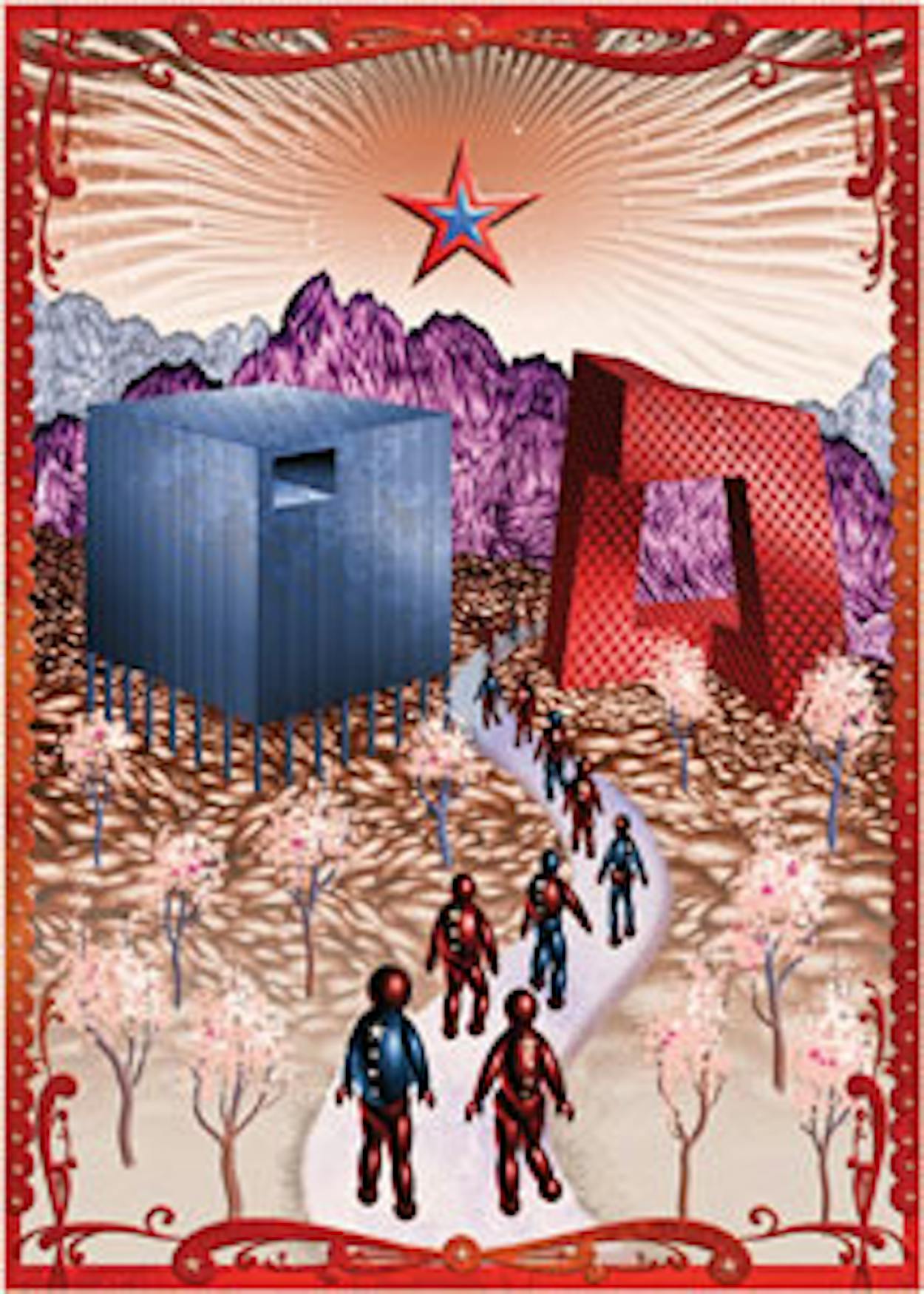

It all adds up to a remarkable if spontaneous architectural duet: the communist bureaucrats in Beijing announcing themselves to the world with exactly the same visual vocabulary as the conservative plutocrats in Dallas. Of course, it’s easy enough to point out that just as our globe is becoming, in economic terms, a “flat earth” (writer Thomas Friedman’s coinage for the increasingly level playing field on which the affluent West and up-and-comers like India and China are now competing), the cultural playing field is also getting noticeably flatter, with architects, artists, and their ideas racing across it at the speed of a broadband connection. But that still doesn’t answer the question of why modernism, having had a stake driven through its heart by critics on both the left and the right, has been revived to lead this new world culture.

To understand what Modernism 2.0 (or 2.1) really means requires some insight into the rise and fall of last century’s version. The familiar mythology is all about monster egos like Picasso and Wright or tormented martyrs like Van Gogh and Pollock. But much of the modernist vision was shaped just after World War I by lesser-known artists and architects who wonkishly embraced technology and mass production, intent on transforming the entire world into a total work of art. Russia’s gifted avant-garde ardently championed the Soviet revolution at its outset, for a few incandescent years creating groundbreaking abstract art and graphic design; their concepts for public buildings remain breathtakingly advanced even today. Germany’s post—World War I ferment produced the Bauhaus, the fabled aesthetic think tank where many of Europe’s most innovative artists, architects, and designers reinvented everything from public housing to typefaces. The politics of this multinational modernism were egalitarian and utopian; oppressed workers, the survivors of the millions who had perished in the trenches of the war to end all wars, were the intended beneficiaries of an era of radical innovation, peace, and progress.

Europe’s new masters had their own vision, however, and in short order both Stalin and Hitler purged their moderns (the latter perceptively denouncing modern art as “nothing but an international communal experience”). By the time World War II was under way, much of the most fecund generation of European modernists—including most of the Bauhaus brain trust—had fled to the United States, sparking a postwar explosion of avant-garde American art and architecture. In 1949 Life magazine asked if Wyoming native Pollock was “the greatest living painter in the United States.” By the mid-fifties, unadorned glass-and-steel boxes in the International style of former Bauhaus director Ludwig Mies van der Rohe had not only claimed New York’s skyline but were transforming heartland cities like Chicago and Houston. And all across America, cultural conservatives could be depended on to complain that modernism was a communist front.

The avant-garde marched on, however, until more-liberal voices turned against a movement that seemed to have lost its social conscience along the way. By the early seventies, even many artists found pared-to-the-bone late modern art a mandarin exercise by and for a cultural elite. Architecture critics protested that cookie-cutter glass boxes had overwhelmed existing neighborhoods, with no respect for picturesque local “context” or customs. Environmentalists regarded the glass towers, inherently cold in the winter and hot in the summer, as energy hogs.

The fall from grace was swift. By the time apostate modernist Philip Johnson, previously America’s most devout Miesian, gleefully announced postmodernism’s formal coming out at the American Institute of Architects convention in Dallas in 1978, he was already building the world’s first postmodern skyline in Houston. It was the ideal pairing: The postmodern disdain for modernist social engineering, along with the boisterous anything-goes aesthetics that freed architects to mix and match historical periods like fashion separates (Johnson might top one building with Gothic spires, another with a little Greek temple), perfectly suited Houston’s unzoned anarchy and unfettered boom-and-bust economy. Soon, buildings dressed up in phony period costumes mirrored the nation’s nostalgic mood as we began to turn back the clock on the New Deal—Great Society social agenda. It was an era that was fittingly bracketed by a pair of two-term conservative “cowboy” presidents, the first having played one in the movies, the other buying his ranch on the eve of his election.

But the tarted-up, selectively remembered past didn’t serve postmodern architects as well as it did postmodern-era politicians; too many overornamented, aimless historical pastiches too often proved that more was a lot less. Meanwhile, a new generation of modernists was also breaking out of the Miesian box but doing so with complex, fluid abstract forms and high-tech “skins” that allowed buildings as open and transparent as Mies’s to be far more energy efficient. The best modernists also became astute urban planners, carefully designing projects that respected their surroundings and historic neighbors. By the beginning of this century, modernism had begun to win back its audience and, in places as far-flung from each other as Dallas and Beijing, attract a fresh generation of clients.

The appeal of the new-look modernism lies, in part, in a revival of the old “international communal experience” that Hitler found so at odds with his vision of Aryan supremacy. In an era of global problems like climate change and terrorism, most of the world has already concluded that the solutions aren’t the exclusive domain of one nation or culture but instead require a global creative consensus; even the lone superpower can’t go it alone. But there’s also a resonance buried deeper in our collective psyche, a paradoxical nostalgia for the future—that is, a need to restore the sense of hopefulness and wonder we used to feel about the future. Throughout the midsection of the last century, utopian World’s Fairs featuring cutting-edge architecture and themes like “The World of Tomorrow” were galvanizing global events. Astronauts were national heroes, not tabloid fodder. Basic scientific theories were the handmaidens of human progress rather than attacks on the authority of ancient scripture. We had fears, but they were worthy of our ambition: A powerful ideological competitor, armed with thousands of nuclear warheads, challenged us daily on air, land, sea, and in outer space. Today our existential threat is a tiny cabal of cave-dwelling primitives.

So perhaps what we see in modernism now is a path back to the future, a chance to renew the optimism and progressive imagination of the mid-twentieth century with the tools of the twenty-first. The first time around we attempted to engineer a modern utopia with an enthusiasm that was naive and a self-confidence that grew arrogant. But after years of trying to make the clocks run backward, we no longer have the luxury of cautious steps; we need some measure of utopian thinking and planning simply to prevent a terrible global dystopia. What we’re telling ourselves in Dallas and Beijing—or even as we wait in line at MoMA—is that the clock is racing forward again, at a pace we never expected, and the answers we need may well be found in our visions of futures past.