This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

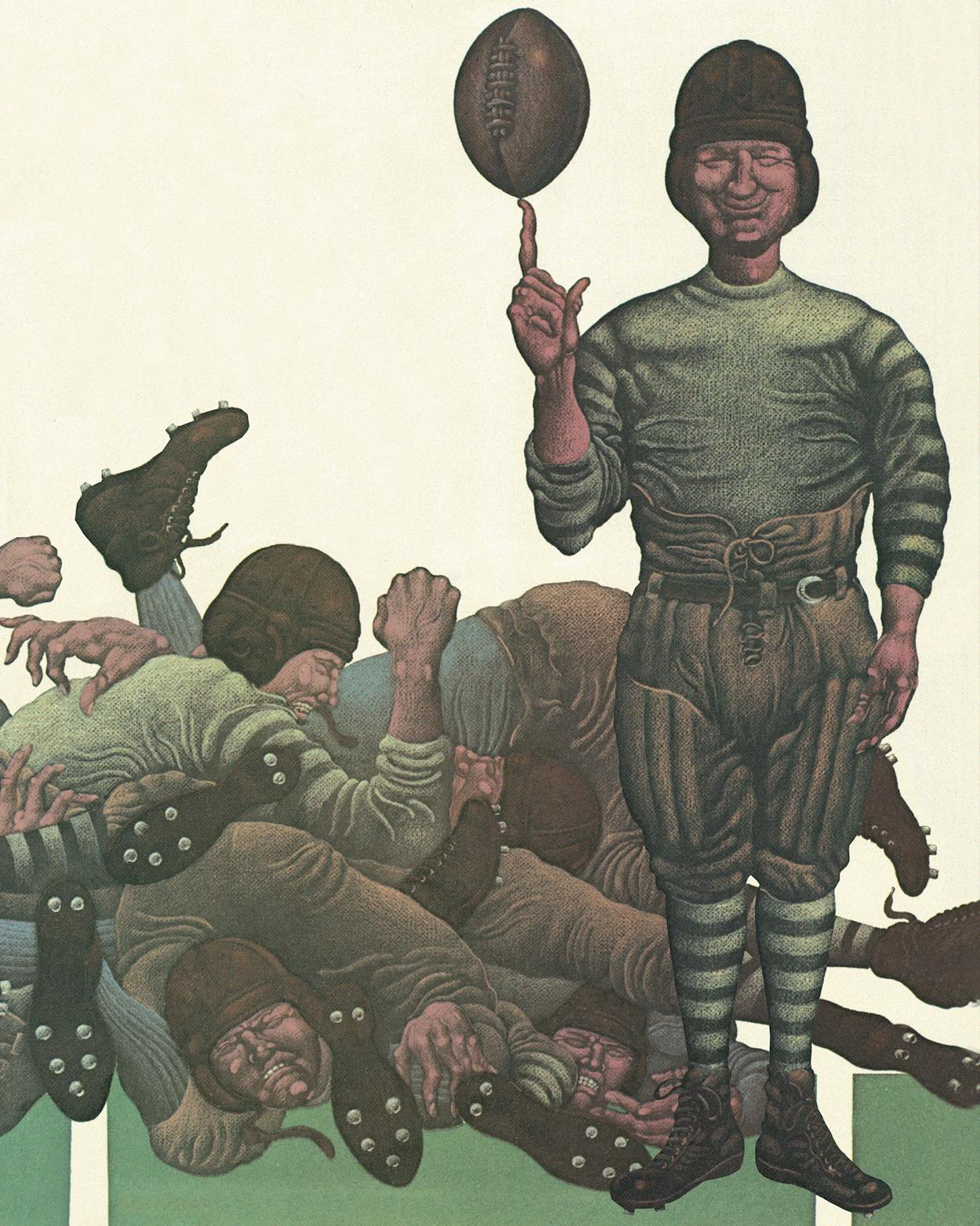

What separates a trick play from the rest of football is the element of creativity. Football has become too much a game of rote. Coaches call it “execution”: doing the same thing the same way play after play. Nothing must be left to the imagination. Do as you are trained and we will win. That’s all very well for the few good teams, but what about the rest? Why should they embrace this orthodoxy, dooming their O’s to get obliterated, play after play, by the enemy’s X’s? Their only hope is to shatter the opponent’s precision, to refuse to play by his rules, to create something so totally new that it renders his endless hours of practice useless.

Alas, the trick play is becoming a lost art today, a victim of the prevailing ethos among football coaches that regards such skulduggery as the closest thing to cheating. Artifice has been all but legislated out of existence. Many of today’s highly technical rules concerning substitutions, uniforms, numbering of players, and putting the ball in play are designed solely to prevent trick plays.

What is strange about this point of view is that deception and legerdemain are as basic to football as brute strength. The quarterback fakes to the fullback, who feints into the line. The linemen pretend to be overwhelmed by rushers so they can race out and set up a screen, and all the while the defense is disguising its pass coverage. Darrell Royal won national acclaim for a wishbone formation that concealed the ball from the defense; yet a few years earlier he was criticized for changing to a jersey color that concealed the ball from the defense.

The trouble with tricks is that they debunk the notion that football is a test of character. Back in the old days, when winning meant no less but image did, football was acknowledged to be a test of wiles. Many of today’s standard offensive maneuvers were originally trick plays—the Statue of Liberty (the passer drops back as if to throw and instead slips the ball to a runner circling behind him), the fleaflicker (a runner takes a handoff, bucks into the line, then turns and flips it back to the quarterback for a pass), and even the reverse. One high school coach sewed football-colored patches to the midriffs of his players’ uniforms; when a play began, every back clutched his tummy and it was impossible to know who had the ball. A coach could go as far as his fertile imagination could carry him.

Resurrecting the trick play could be the answer to all of football’s current problems. Worried about high costs? People will pack stadiums trying to spot a lonesome end. Worried about the perennial have-nots? UT and Arkansas can’t program their robots for sucker plays. Worried about cheating in recruiting? Make brains as important as brawn and even Rice could win the Southwest Conference.

In compiling our endangered species list of trick plays, we contacted coaches from around the state. A few admitted to knowing a thing or two about trick plays—perhaps they had read the 1969 collection published by Texas Football magazine and known to all connoisseurs—but none confessed to a fondness for them. Nor did any know about my modified triple-reverse, double-handoff flanker option pass to the quarterback. It’s one trick play not explained below. That’s because next January, when the Cowboys and Oilers meet in the Super Bowl, I’m going to auction it to the high bidder.

The Tackle’s Revenge

Pity the poor offensive tackle. He labors in obscurity, throwing himself play after play against hostile bodies, never getting a chance to touch the ball himself unless something has gone terribly wrong. The tackle-eligible play is his salvation, a ruse that should gladden the hearts of underdogs and anonymous souls everywhere. It takes advantage of the fact that in a pro-style offense virtually every play starts with the same basic formation. The split end lines up, say, on the right, far outside the right tackle, while the flanker goes to the left side of the field, well beyond the tight end and a yard or so behind the line of scrimmage. Under the rules, only the two ends and the backs, including the flanker, are eligible to go downfield and catch passes. Boring, boring—especially for the poor right tackle, who at first glance looks like an end, yet is proscribed by law from sharing in the glory. But a tiny shift in position can transform him into an eligible receiver. The flanker lines up one step forward, becoming an end, while the split end drops back one step like a flanker. Free at last, the tackle fakes a block, lurches into the secondary as though carried by momentum, and, ignored by scornful defenders, awaits the ball. Why isn’t this play tried more often? Because the clumsy oaf usually drops the ball.

The Lonesome End

The apotheosis of football chicanery, the lonesome end ploy requires only a favorable location on the field and a coach bent on larceny. It must be set up on the previous play, which is run toward the sideline in front of your own bench. Bodies scatter everywhere, and who is to notice if one of them doesn’t make it all the way back to the huddle—in fact, remains with his back to the field, apparently part of a cluster of standing benchwarmers? Actually, he is positioned in bounds, but from the defense’s vantage point, he blends in perfectly with the bench.

A nice touch is to send in a last-second substitute, who is then waved off by the offense as though unneeded; in the unlikely event that someone on the defense is counting the offensive players, this will shake his confidence in his arithmetic, which probably wasn’t great to begin with. When the ball is snapped, the unencumbered lonesome end streaks downfield for a pass. This play will probably become a staple for the Dallas Cowboys, who spent most of last season establishing the fact that they never knew how many men they had on the field.

Trick Formations

So you think the Cowboys are hopeless because they never call the right defense to stop Terry Bradshaw, right? All right, try this one. The enemy approaches the line of scrimmage in a formation you’ve never seen before. Out on the far left is a clump of five players—three linemen, two backs. Equally far to the right is another clump of four players—three linemen, one back. This leaves just the center and the quarterback in the middle of the field. You can see what’s going on: if you don’t send enough defenders to one side or the other, the quarterback will toss a screen pass to the appropriate clump and superior numbers will do the rest. So you instinctively choose a mirror defense: five defenders for clump A, four for clump B, one rusher, one deep safety.

Wrong! You’ve just fallen for a trick formation that’s as old as X’s and O’s. The play is designed for the quarterback to run the ball up the middle, going to whichever side the lineman doesn’t and letting the center block the safety. Better luck next time.

Sucker Plays

Football has gotten too technical. The X back through the three hole. The 52 Y veer pass. Whatever happened to you-go-long-everybody-else-block? Or better yet, the hydrophobia play. There’s one anybody could understand. A flanker collapses, clutching his throat, foaming at the mouth. When defenders rush to offer assistance, the ball is snapped and a pass receiver romps through the deserted secondary. As his team lines up for the extra point, the flanker is on the bench getting first aid—a towel to wipe off the shaving cream. Another sucker play calls for the quarterback, after his team has been hit by a fifteen-yard penalty, to initiate an argument with the referee by claiming that only five yards should have been assessed. Before the official can respond, the quarterback screams for the center to give him the ball. The center raises up and hands it over, and the quarterback starts taking big strides forward, protesting all the while. With a little luck, the entire penalty can be wiped out before the defense catches on. One of the most famous sucker plays was invented by Notre Dame end Knute Rockne in the 1913 Army game. On three straight pass plays, Rockne hobbled downfield while the quarterback threw elsewhere. Apparently unable to run, he was acting as a decoy—until the fourth play, when he streaked by the mesmerized Army defenders for a 35-yard touchdown pass.

The classic sucker play was pulled on the 1965 Texas Longhorns by Texas A&M. Destined to become famous as the “Texas special,” the play began innocuously when Aggie quarterback Harry Ledbetter tossed a quick swing pass to his wingback. Like most of Ledbetter’s passes, it arrived on one bounce. Ledbetter, who later went into politics and narrowly lost a bid for state treasurer in 1978, stamped his foot in disgust. So did the wingback. The Texas defense relaxed, thinking the play was over. But they had failed to notice that wingback Jim Kauffman had lined up deeper than usual: the toss was not a pass but a lateral; the play was not dead but alive. Kauffman, normally a defensive back, made his one offensive play of the year count: a touchdown pass to Dude McLean, good for 91 yards and a conference record.

The Hidden Ball

In the fourth quarter of last year’s Oklahoma-Nebraska game, the Cornhuskers were on the OU fifteen-yard line and Sooner fans were pleading for a fumble. Nebraska put the ball on the ground, all right, but by design: the quarterback covertly deposited it behind the right guard’s legs and ran off to the right along with most of his team—except for the guard, who plucked the ball off the ground and ran left, into an area recently vacated by the Oklahoma defense. The old hidden-ball trick had worked again. This subterfuge is almost as old as the game itself. Before Jim Thorpe, the Carlisle Indians won games by having the quarterback slip the football under the center’s jersey. Though straitlaced rulemakers keep coming up with new decrees (a center may no longer maneuver the ball between his legs and into the knee crook of a guard), such prudery can still be overcome with a little imagination. Uvalde High used a variation—substituting for the offensive right guard a fast defensive back who ended up carrying the ball—to defeat a great Brenham team in the 1972 Class AAA semifinals. To this day Brenham (now Nederland) coach Lloyd Wassermann insists the play was run illegally, but he was sufficiently intrigued to try it once himself. Result: a lost fumble.

- More About:

- Sports

- TM Classics

- Football

- Dallas