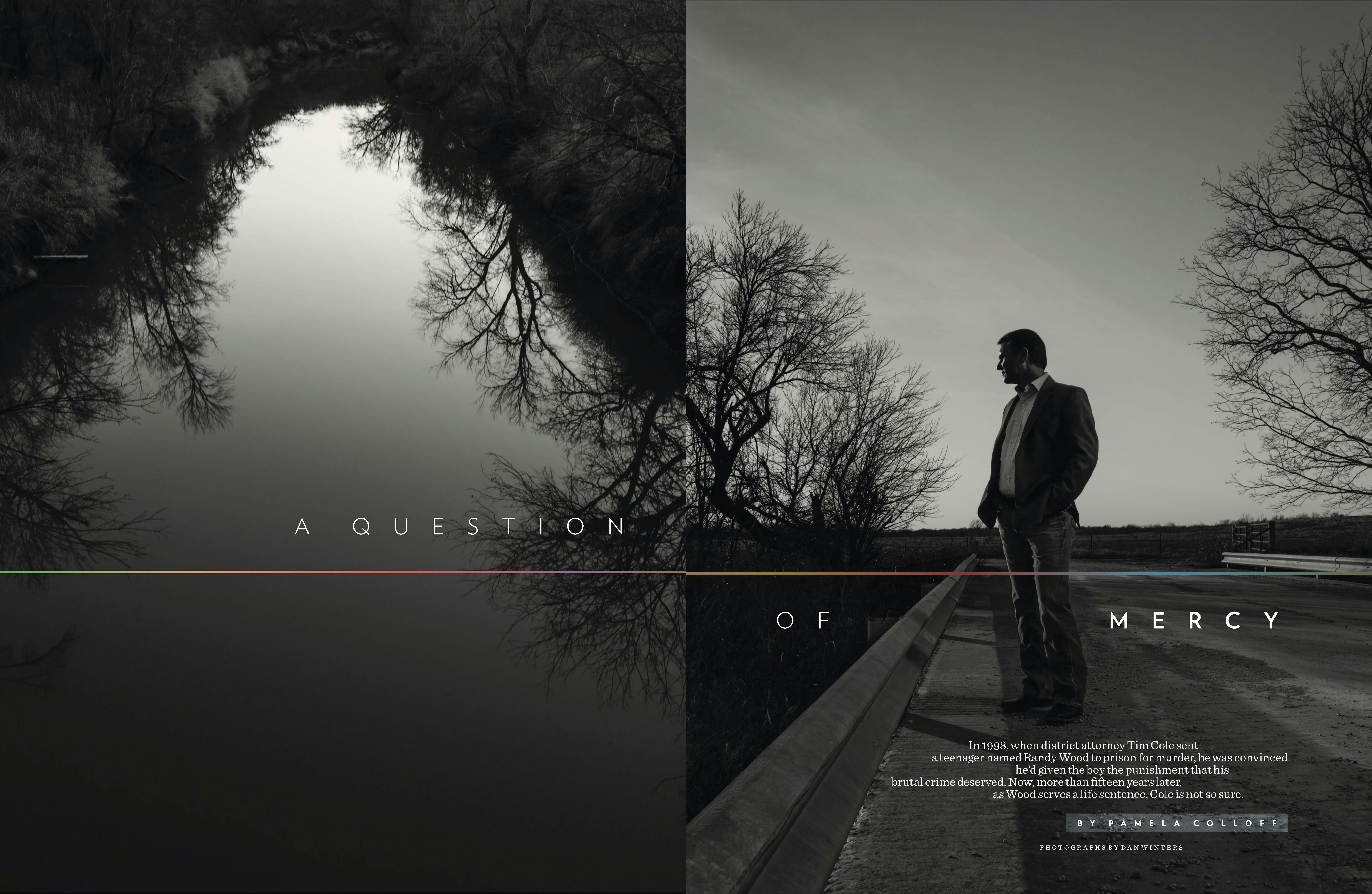

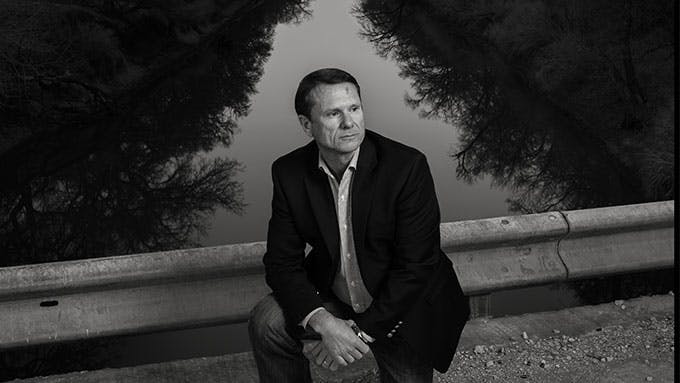

Every so often during the five years that Tim Cole worked on the Heather Rich case, he would leave the courthouse in the evening after the North Texas sky had grown dark and drive to the Belknap Creek bridge, just south of the Oklahoma border. The winding stretch of blacktop that led there eventually came to an end, giving way to a dirt road. Cole, the district attorney of Montague County, would follow the road north as it meandered toward the Red River, until he reached a backwater creek. He might spend an hour out there, standing on the old cement bridge, without seeing a single pair of headlights cut through the darkness. Cole prepared for the trials of Heather’s killers this way, turning over the details of the case as he stared down at the murky, slow-moving water where her body had been found.

Heather was from Waurika, Oklahoma, a town of 2,064 people that sits twelve miles north of the Red River, along what was once the Chisholm Trail. A pretty high school cheerleader, she was just sixteen—a year younger than Cole’s own daughter—when she was killed, on October 3, 1996. The killers were three teenage boys, including the captain of Waurika High School’s football team, who had engaged in a night of heavy drinking and sex before Heather was shot in the head. Long before “Steubenville” and “rape culture” became buzzwords on social media and 24-hour cable news shows, Waurika found itself at the center of a now-familiar conversation about lost values and teenage dissolution. Where were the parents? How had something this horrendous happened in such a small, tight-knit community?

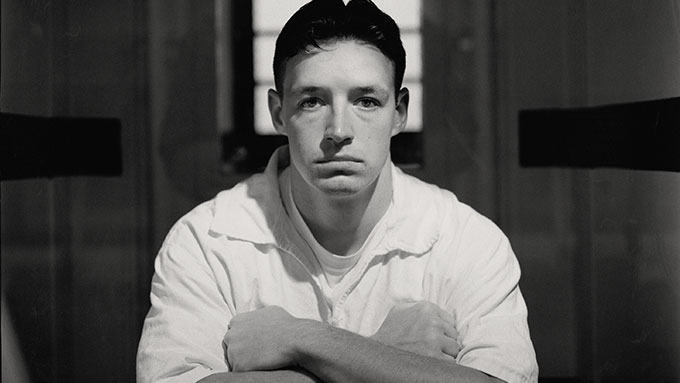

Two of the teenagers who were charged with Heather’s murder, Curtis Gambill and Josh Bagwell, were bad kids as far as Cole was concerned. Curtis had a criminal record and a violent history and had been briefly committed to a mental hospital. Josh too had had brushes with the law. Except for an initial, misleading account of the crime that Curtis gave to the Texas Rangers, neither one had cooperated with the investigation or expressed any remorse. But the DA puzzled over how Randy Wood—the soft-spoken, well-regarded captain of the Waurika Eagles—had gotten mixed up in such an appalling crime. Cole had made a name for himself securing the harshest penalties a jury would hand out, but he was flummoxed by what to do with Randy. Cole knew that the seventeen-year-old had never been in trouble before, and he believed Randy was being truthful when he told investigators that he had never intended for Heather, who was a friend, to be killed that night.

To win convictions against the other two teenagers, Cole needed Randy to testify for the state and describe what he had seen take place on the Belknap Creek bridge. Before entering into any kind of agreement with him, though, Cole wanted to verify that the boy had been candid with investigators. One afternoon following his arrest, Randy was transported from his jail cell to the office of a respected polygraph examiner in Dallas, where he underwent a lie detector test. Randy told the examiner that it was Curtis who had shot Heather on the bridge, and that afterward, Josh and Randy had thrown her body into Belknap Creek. The results showed no deception.

The fact that Randy had not actually fired the gun, Cole knew, did not help the boy’s case. Under Texas law, all three teenagers—not just the gunman—were considered equally responsible for Heather’s murder. So Cole offered Randy a deal: in exchange for his testimony, he could plead guilty to murder, making himself eligible for parole in thirty years. (If he went to trial and was convicted of capital murder, he would receive an automatic life sentence and not be considered for parole for at least forty years.) Randy took the deal, and as Cole prepared to bring the two other teenagers to trial, he and his investigator began to visit Randy in jail, to glean more information before he testified for the prosecution.

Cole tried to establish a rapport with the teenager who sat across from him in the sheriff’s private office, studying the floor. Upon learning that Randy liked cheeseburgers, Cole began bringing lunch from a nearby burger stand. Once, with his investigator at the wheel, Cole took Randy, who remained in shackles, for a drive around the county so that he could glimpse the outdoors. They discussed Randy’s hard-luck upbringing and the things they shared in common, having grown up playing football in small towns on opposite sides of the river. Mostly, they talked about the case. Randy did not deny his role in the crime or make excuses for what he had done; he said only that he had not known how to stop what was happening when they reached the bridge. He had been afraid of Curtis, who wielded the shotgun. Each time Cole visited, Randy told the DA that he was haunted by his failure to stop Heather’s murder.

Then, two days before he was set to testify in Josh’s trial, Randy backed out of the deal, saying he could not plead guilty to something he did not do. Cole was devastated, certain that Josh would avoid punishment. The next day, however, Randy explained that he still wanted to testify, without the protection of a deal. By taking the stand with no agreement in place, Randy would be incriminating himself under oath while awaiting his own capital murder trial. Over the frantic protests of his attorney, the boy did just that, recounting to jurors what he had seen that night. Cole was dumbfounded. If Randy understood that he had doomed himself to a future trial at which there would be no presumption of innocence, he didn’t seem to care; he said he wanted everyone to know that he was speaking the truth—something he felt he owed Heather and her family. It was the legal equivalent, Cole remarked, of committing suicide in the courtroom.

With Randy’s testimony, Cole was able to secure a capital murder conviction and a life sentence for Josh. By then, Curtis had pleaded out, earning himself a life sentence as well. When Randy turned down another plea bargain before his own trial, again refusing to say that he had killed Heather, the outcome was a foregone conclusion. He had forced Cole’s hand. The DA prosecuted Randy for capital murder and asked a jury to find him guilty. He was convicted and handed an automatic life sentence.

Years later, long after Cole had boxed up his case files and stowed them in the attic of the Montague County courthouse, he would find himself thinking about Randy. Cole had not lost sight of the horror of Heather’s murder or of Randy’s own culpability; he would never forget the awful details he had recounted to jurors during Randy’s trial. But the prosecutor was moved by the knowledge that the teenager had tried—too late—to make things right. Seventeen was an awfully young age to be given up on, Cole thought, and he wondered sometimes if Randy was not deserving of mercy.

Last summer, Cole was sitting at his desk, surrounded by the files of other felony cases he needed to attend to, when he began to do some quick calculations. He was startled to realize that Randy was 34 years old. The teenager he remembered had spent half his life in prison. Cole began to wonder: What would the right punishment have been for Randy? What number of years would have accounted for the dreadfulness of what he did, while also considering the good? And then another thought hit him: What would it be like to sit and talk with Randy again?

Heather had slipped out her bedroom window shortly before midnight on October 2, 1996, having made plans to meet up with Josh. It was their first date. Josh was a senior at Waurika High School and came from a wealthy family who owned land along the river. His mother, who was divorced, was an attorney in Lawton, an hour’s drive away, and his grandparents, whom he lived with, exerted little control over him. He had a predilection for sports cars and assault rifles, both of which he owned, and he bristled at authority. (Once, after he was arrested for drunk driving, he scuffled with police officers, yelling, “I want my f—ing attorney!”) Heather, a sophomore, was elated that he had said she could ride on the back of his Dodge Stealth in the homecoming parade later that month.

In a time when teenagers were not ceaselessly interconnected by texting and Twitter and Instagram, Heather was rarely content to stay at home. Sometimes she would climb out her window to smoke a cigarette or catch a ride and cruise all three blocks of Waurika’s mostly shuttered main drag. Three years earlier, her home life had been plunged into chaos when her father, Duane, an electrician for a utility company, was horribly burned on the job after a transformer blew up. To support the family, her mother, Gail, had purchased the local Subway franchise and worked constantly to make ends meet. Heather put in long hours at the family business and helped care for her father during her mother’s absences. She began acting out in self-destructive ways that fall, discreetly cutting herself with a razor blade. Less than a week before she sneaked out to meet Josh, she was suspended from school for three days after she was caught drinking while leading cheers at a Waurika Eagles football game.

When Josh was late to pick her up that night—the plan had been for him to wait by the church near her house at midnight—she decided to strike out on her own, walking nearly a mile down Waurika’s darkened streets to the travel trailer behind his house, where he had mentioned that he and some friends would be hanging out. No one was there, but she decided to wait.

When Josh arrived at the trailer, he was accompanied by two friends of his, Curtis and Randy. The boys had spent the evening draining a bottle of whiskey. Besides football, there was little else to do in Waurika. There was no movie theater or coffee shop or public park, only a Sonic in Comanche, seventeen miles away. On weekends, teenagers drove the back roads out to Lake Waurika or headed into the country to pasture parties, where methamphetamine—the cheap, homemade speed that was becoming popular in North Texas and southern Oklahoma—was passed around as often as marijuana. Heather had smoked pot before, and she had tried meth that fall, but despite her best efforts, she was not much of a partier; a few beers left her unsteady on her feet.

At the trailer, Curtis, Josh, and Randy began working their way through a case of beer. It was a Wednesday night, and there was school in the morning, but none of them much seemed to care. Their plan, if they even had one, was to drink themselves into oblivion.

Randy was already halfway there. For him, the evening was not unlike many others. He often had the dazed look of a kid in his own world. Randy had first smoked pot in the third grade, after stealing it from his mother, Kathy, who was an avid partier. He was fourteen, he remembered, when he got high with her for the first time. One night during his junior year of high school, he had come home to find Kathy and her dealer sitting beside a mound of meth on the kitchen table; he recalled his mother instructing him to take some and leave. Kathy did not know who his father was, and she had moved him all over Oklahoma when he was a kid, so much so that he had attended three different schools during the fifth grade alone. Funny and easygoing, Randy was universally liked wherever he went, but no matter how many times he started over, he had never been able to leave his drinking and drug use behind. Only one adult—a high school history teacher who took him aside his freshman year—had ever warned him to slow down.

Of the three boys who were at the trailer that night, Heather knew Randy best. They had dated before, although things had never gotten serious. She had brought him with her to First Assembly of God Church and helped him with his homework, which he struggled with. He had ferried her around Waurika in his grandmother’s old brown Cadillac Fleetwood, the only car his family owned. Once, after driving Heather to an orthodontist appointment in Duncan, half an hour away, he had let her take the wheel of the Cadillac for a heart-stopping ride along the shoulder of U.S. 81. That was as exciting as things ever got. There had never been much of a spark between them, just a comfortable friendship. Not long after the start of school that fall, he had broken things off after hearing that she had gone skinny-dipping at a coed pool party without him.

The outlier that night was Curtis. The wiry nineteen-year-old did not attend Waurika High, and Heather had never met him before. He was from Terral, a tiny town south of Waurika on the cusp of the river, and he was a drinking and hunting buddy of Josh’s. Randy had met him one summer when they both worked in the watermelon fields, loading ripe fruit into the backs of semi-trailers. On their lunch breaks, they had gotten high together, but Randy had seen little of him since. Randy knew nothing about Curtis’s past—how he had spent years in juvenile detention centers and had broken out of each one. How he had brought an unloaded gun to school and threatened to kill his teachers. How he was eventually kicked out for terrorizing other students. How he was rumored to have slaughtered neighbors’ livestock. How he had once boasted that his fantasy was to kidnap and rape a girl, then “blow her head off.” All those details would emerge later, during the investigation. That night, Randy just thought he was someone to get wasted with.

“I had just finished football practice and was sitting at my grandmother’s house when Josh and Curtis stopped by,” Randy told me one morning last year at the James V. Allred Unit, a maximum-security prison outside Wichita Falls. He had agreed, somewhat reluctantly, to recount what had happened on the night that Heather was killed. (Randy had spoken to me before, in 2002, when I chronicled the case for Texas Monthly in a story called “A Bend in the River.”) He was uneasy as he began, but as he spoke, the words came to him quickly. “Josh said, ‘I’ve got a bottle of whiskey—let’s go,’ ” he continued. “So we took off and drove around the lake. We passed around the bottle of whiskey until it was gone.

“It was almost dark when we went back to town. A guy we knew who was a few years older than us bought us a case of Budweiser. Heather had left a message for Josh earlier, so he called her back from a pay phone, and they made a plan to rendezvous at midnight. We went and bought some chips and cheese, and we tried to round up some more people, but no one wanted to go to a party on a school night. The three of us went to Josh’s house and told his grandparents we were going to play dominoes in the travel trailer. We took a radio out there and started drinking.

“When we went to pick Heather up, she was already gone. She wasn’t waiting at the church, and there was no answer when I tapped on her bedroom window. When we got back to the travel trailer, she took us by surprise because she was just sitting there, waiting on us. We all went inside, and she grabbed a fifth of gin that Josh had gotten out of his grandparents’ liquor cabinet. I asked Josh to give me the keys to the truck so me and Curtis could get out of there, and we took off.

“We drove the back roads all the way to Comanche, but we couldn’t find the girls we were looking for, so after a while we went back. Josh answered the door and said, ‘Let me get dressed.’ I remember I was opening another beer when I saw that the bottle of gin was almost empty. Heather was in the bedroom, and she came out. She had no clothes on, and she could hardly stand up. She started telling me she was sorry.

“I guess she thought I was thinking bad of her for being with Josh, because me and her had never done it. We went back into the bedroom, and she kept saying she was sorry. She was really drunk, and I was pretty far gone myself. She was naked and she wasn’t saying no, so I started touching her. I was getting ready to have sex with her but she passed out, so I stopped. I grabbed my clothes and put them back on and got another beer.

“At some point, Curtis went back there with Heather too. Whatever he did, I didn’t see it. I didn’t hear anything. When he came out, he said, ‘She’s awake.’ But when I went back there, she was still passed out.

“We were all three drinking beer and talking, going back and forth, when Heather woke up and screamed. Then she passed out again. She did that twice. Curtis started freaking out. He said, ‘She’s going to say we raped her.’ He was on probation for a shooting incident; he’d shot at another guy’s truck when it was going down the road. He said, ‘I’m not going down for rape.’ And that’s when he started talking about killing her. I thought he was just blowing smoke. We sat there and kept drinking beer. A few minutes later, Curtis told Josh to go get the truck. He told me, ‘Get her dressed.’

“I figured we were going to drive around and get her sober and then take her home. I never thought Curtis was actually going to kill her. Josh went and got the truck and pulled up outside the travel trailer. I put every stitch of clothing back on her. I laid her down in the back seat of the truck, and we all got in front.

“Josh started driving out of town, over a back highway to Ryan and then to Terral. We drove around for a long time. Finally Curtis got behind the wheel and said, ‘I know where to go.’ He drove until we got to the Belknap Creek bridge. I didn’t know where the hell we were at. It was a very rural area. The road going out to the bridge had grass on it that was knee-high. Looked like an old wagon trail. That was the first time it started getting real, that Curtis was fixing to kill her.

“He said to me and Josh, ‘Get her out and put her on the bridge.’ We sat her down against the guardrail. She was still completely passed out. I was on autopilot at that point; I didn’t feel like I could stop it. It seemed hopeless. I’d like to tell you that if I could do it all over again, I would have saved Heather, but I did what I did to survive. I was scared of Curtis. I was a coward. I got back in the truck and put my head in my hands.

“I don’t know how much time went by, but after a little while, I heard the first shot. And then a bunch more. I was thinking there was no way he had shot her. He had a twelve-gauge shotgun. There was no way he’d put all those shots in her. He must have chickened out and fired a bunch of warning shots into the air. But when I got out of the truck, I saw a pool of blood.

“Josh used a shoestring to tie a rock around her ankle. I was just kind of standing there in shock. Curtis started loading more shotgun shells, and I knew he’d kill me too if he got it into his mind that I wasn’t on board. So I did what I was told. I helped them throw her over into the water. I picked up the shotgun shells. I covered up the blood on the bridge with dirt. And then we left.”

During Cole’s meetings with Randy, he sometimes had trouble believing that the mild-mannered kid who sat across from him was the same person who had dressed an unconscious girl and carried her to the bridge where she would be murdered. But Randy did not gloss over his actions. He had kept quiet at first, in the days that followed Heather’s disappearance, when sheriff’s deputies had fanned out across Waurika, looking for clues. He had feigned ignorance after Heather’s body was found, when Texas Ranger Lane Akin paid him a visit one day after football practice, asking where he had been on the night she was killed. He finally came clean when he was brought in for questioning, after the double-aught buckshot that was recovered during the autopsy was connected to Josh and the murder weapon was traced back to Curtis, who told investigators that Randy had been the shooter.

Cole never gave any credence to Curtis’s account of the evening, which was that Randy had shot Heather in a jealous rage after she had sex with Josh. The DA found that scenario implausible for a number of reasons, beginning with the fact that Randy had no prior history of violence. The investigation had also revealed that the Mossberg 12-gauge shotgun that was used to kill Heather belonged to Curtis and that the crime scene was a place known only to him; he had frequently gone fishing there as a kid. Yet as much as Cole trusted Randy’s telling of events, he was also clear-eyed about what Randy had left out. Cole had been skeptical when he heard Randy claim in his first statement to law enforcement that he had refrained from touching Heather in the bedroom after she passed out, and Cole asked investigators to press him on that point. Under further questioning, the seventeen-year-old conceded that he had penetrated her with his finger. “Randy may not have considered that rape, but the law does, and I do,” Cole told me. “There’s no question that he was not just an observer to this crime; he was also a participant. That was very hard for him to accept.”

Cole found himself consumed by the case. Four years into his tenure as DA, his workload was already staggering; he often had four to six murder cases pending at any one time, even though only around 30,000 people lived in the three-county area over which he had purview. Montague County, in particular, has always had a seemingly disproportionate share of violent crime—a consequence of isolation, rural poverty, bad luck, or all three. Cole was the lone lawyer employed by the cash-strapped DA’s office, and the young married father of three immersed himself in his work, sleeping and eating little during trials, sometimes dropping more than a dozen pounds between jury selection and the time a verdict was handed down. He answered investigators’ calls at odd hours of the night and put a premium on hurrying out to crime scenes so that he could later describe them more vividly to a jury. No other case, though, had gripped him quite like Heather Rich’s. When he had first gotten the call that a rancher had found Heather’s body floating in the reeds of Belknap Creek, Cole had rushed to the bridge. He saw that the sixteen-year-old had been shot nine times—once in the head, eight times in the back. It was an image he often revisited as he lay awake at night, pondering the case.

Cole had grown up downriver of Belknap Creek, in the small town of St. Jo, where his father was a Church of Christ preacher and ran the local newspaper along with his mother. He moved to Austin to go to law school and served as counsel for Governor Bill Clements before coming home to cut his teeth as an assistant prosecutor in nearby Wise County. He was 31 when he challenged the three-term incumbent Montague County DA under the banner “It’s time for a change,” declaring that he would offer fewer plea deals and not shy away from taking more cases to trial if he was elected. He won handily, becoming one of the youngest DAs in the state when he took office in 1993. Unlike a big-city lawyer, he never needed a jury consultant; he knew many of the prospective jurors in any given jury pool. He was also often acquainted with the people he was prosecuting. (He sent two high school classmates, from a graduating class of eighteen, to the penitentiary: one for habitual drunk-driving, the other for child abuse.) Despite his familiarity with some of the accused, however, he was hardly lenient. The first case he ever tried involved a man charged with stealing a tractor, for whom Cole won an unstinting 45-year prison sentence.

His tough-on-crime posture, which earned him big margins at the polls, left little room for nuance. “I grew up always knowing what the right thing was and the wrong thing was,” Cole told a reporter a decade into his tenure as DA. “It was very clear. I do look at things in black and white.” He felt the certitude of that moral code in the Rich case, especially in his initial decision to seek the death penalty for Curtis. It was only after agonizing with Heather’s parents that Cole had offered Curtis a deal, during jury selection at his trial: in exchange for a life sentence, he would abandon his story that Randy was the killer, admit that he himself had shot Heather, and testify against Josh. The Faustian bargain was necessary, Cole felt, because the case against Josh—who had invoked his right to remain silent and whose family had hired a high-dollar lawyer to defend him—was the weakest of the three. (When Curtis later refused to stick with the plea deal and changed his testimony in Josh’s trial, Cole tried him for conspiracy to commit capital murder, for which Curtis received an additional life sentence.) Cole was convinced that Josh, too, deserved life in prison. While awaiting trial, he had tried to incite a riot on his cell block, threatened to kill several guards, and attacked a police officer.

Only Randy gave him pause. While Randy’s co-defendants sneered at Gail Rich when she addressed them at their sentencing hearings and tried to convey the devastation of losing her daughter, Randy faced her grief head-on, asking in advance of his trial if he could meet with her and her husband, Duane. As the DA sat in on the unusual face-to-face visit, he could not help but be moved as Randy looked the Riches in the eye and choked out a few words of apology before breaking down and asking for their forgiveness.

“At one time, I could have killed all three of [you] with my bare hands,” Duane told the teenager who sat before him, his voice shaking with emotion. He thanked Randy for testifying against Josh and for meeting with them. “Being a Christian,” Duane added, “I can’t have hate in my heart for you.” Gail agreed, telling him that she could see his remorse was sincere and that it would help her and her husband to heal. She said that she wanted to write to him and asked if she could send him Heather’s photo and a Bible.

Randy’s repentance did not change the fact that Cole still had to prosecute him. The DA did not pull any punches once The State of Texas v. Randy Lee Wood began. “You know what the defense really boils down to in this case?” he asked jurors. “They want you to say, ‘He testified against Josh Bagwell, he said he was sorry, he’s not such a bad guy—let him go.’ ” But his acts of contrition, Cole told them, were irrelevant. “This is not television,” he reminded them. “This is not something where we wake up the next morning and we can say, ‘I wish I hadn’t done that,’ and it goes away. It’s real. Heather Rich was a real sixteen-year-old girl, and he helped take her life. And no matter how bad he feels about that, he is still responsible for it.”

According to the law, Cole continued, it did not matter that Randy had not fired the gun or had not wished Heather dead. In Texas, the “law of parties” erases the distinction between killers and accomplices, finding that a person can be held criminally responsible for the conduct of another if he participated in the crime. By virtue of the fact that Randy had assisted Curtis, he was guilty of capital murder. “He could stand here all day long and tell you that his intent was not to assist in the commission of this crime, and his actions cry out differently,” Cole insisted. “He’s guilty. He must pay the consequences of his choice.”

The jury agreed, and on August 25, 1998, Randy was convicted of capital murder and handed an automatic life sentence. Cole watched as Randy, then nineteen, was led from the courtroom in handcuffs and leg irons. As the DA gathered the papers at his table, he was relieved that the trial was over. Yet he hardly felt triumphant. “It was not a moment of celebration,” Cole told me. “There was no joy or happiness. I had a deep, deep sense that another young life had been senselessly wasted.”

After Randy went off to prison, Cole moved on to the next case. He prosecuted a serial killer, a motorist who had intentionally killed a police officer with his car, and a man who had murdered his mother on Mother’s Day, as well as a motley crew of cattle rustlers, child molesters, and meth cooks. He won reelection for his third term in 2000 and again for a fourth term in 2004. In 2005 he raised his profile statewide when he began serving as president of the Texas District and County Attorneys Association, a position for which he frequently traveled to Austin to testify before state lawmakers. He also began preparing for yet another high-profile murder trial—that of Vickie Dawn Jackson, a nurse who had spent years quietly killing her friends and neighbors at the public hospital in Nocona.

Despite his success, however, Cole’s personal life was coming apart. Early in his career, he had moved his family to the Dallas suburb of Lewisville, where his youngest son, Bryant, who is severely autistic, could receive superior services from the local school district. Ever since then, Cole had divided his time between Lewisville and St. Jo, an hour’s drive away, so that he could fulfill his legal obligation as DA to maintain residency in his district. His worry for his son was overwhelming; Bryant, who was then fourteen, had never spoken a word. The strain of Cole’s family responsibilities, along with his crushing workload, had accelerated a drinking problem that had dogged him since he was a teenager. More than once, local law enforcement officers pulled him over, only to let him go with a friendly admonition that he should probably head home. In early 2006, he and his wife of 28 years filed for divorce.

On the night of July 4, 2006, a Lake Texoma park ranger shone his flashlight into a pickup truck parked by the side of the road and spotted the DA sitting in the driver’s seat, drinking a beer. The discovery followed a report that an erratic driver had been spotted in the area. Cole consented to a Breathalyzer test, which showed his blood-alcohol level to be .15, nearly twice the legal limit. District attorneys who are arrested on drunk-driving charges are not legally obligated to step down, and a number of DAs, as well as judges and other elected officials, have chosen to remain in office after similar arrests. But Cole’s arrest was front-page news, and as the area’s chief law enforcement official, he felt that it would be hypocritical for him to stay. Three days after his arrest, he announced that he would be resigning that fall. “The last year has been one of great personal hardship for me, but there is no excuse for this behavior,” he told reporters inside the Montague County courthouse. “It is in violation of the public trust in my office.”

Cole pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor drunk-driving charge, agreeing to pay a fine and serve probation. And just like that, his marriage, his career as a prosecutor, and his vaunted status as DA were over. “I won’t tell you that I never contemplated suicide,” Cole told me. “I did many times.” Needing to earn a living, he went into private practice, briefly partnering with a defense attorney he knew before opening his own practice in Nocona. In his office on the corner of the two-stoplight town’s main intersection, he took whatever work came through the door. He drafted wills, filed divorce papers, and defended people on small-time drug possession charges, but the particulars of small-town lawyering were hardly challenging. Each night he went home to his house at Nocona Lake, where he lived alone.

It was not until he began dating a woman who worked in the county attorney’s office, Sherry Nobile, that he started feeling “like there was a reason to live,” he told me. He began attending a twelve-step program, and there were times when he stopped drinking for months, even a year at one stretch, though he continued to falter. “I came to see how people—good people—could make terrible mistakes,” Cole said. “And how maybe they shouldn’t have to pay for them for the rest of their lives.”

In the fall of 2009, thirteen years after Randy’s arrest, Cole received a phone call from an attorney in Dallas who had been hired by a cousin of Randy’s named Denise Horner. A retired financial analyst living in the Dallas suburbs, Horner had taken a recent interest in her cousin’s case, and she had set her mind to getting Randy’s sentence reduced.

Commutations, or “time cuts,” can be granted when an inmate’s punishment is deemed to be unduly harsh; President Barack Obama recently did this for eight federal inmates serving lengthy sentences for nonviolent crack-cocaine offenses. But for Randy, who was convicted of capital murder, the odds of winning a commutation were slim. Governor Rick Perry has commuted sentences in capital murder cases when he was mandated to do so by law. (When the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed the execution of the mentally disabled in 2002, for example, he commuted eligible inmates’ sentences to life in prison.) Yet in his more than thirteen years in office, the governor has granted a time cut to only one other inmate convicted of capital murder. In 2007 he commuted the death sentence of a man named Kenneth Foster to life over concerns that Foster, the getaway driver in a botched San Antonio robbery, had not received a fair trial.

Horner knew that getting Randy a time cut was a long shot at best. To have his sentence reduced, at least two of Montague County’s three elected officials—the sitting DA, the district judge, and the sheriff—would have to sign off on the idea, as would the Board of Pardons and Paroles and then Governor Perry. Still, Horner had her attorney, Danny Clancy, contact Cole to see if he would be willing to support the effort.

It is not every day that a former DA pledges to try to get the sentence reduced of someone he once prosecuted for murder, but Cole agreed to do what he could on Randy’s behalf. In truth, Cole wished he had not tried Randy for capital murder at all but had instead prosecuted him for a lesser charge: conspiracy to commit capital murder. Doing so would likely have earned Randy a 25- or 30-year sentence, which Cole now believed was an equitable punishment. But it would also have created an intractable problem: the perception that he and Randy had always had a secret deal, which Curtis and Josh could have raised on appeal. And it would have cost Cole with his constituents. “I was still a politician—I was an elected official—and DAs are reluctant to do things that make them look weak,” he said. “That’s the evolution I’ve had: now I don’t necessarily see a lighter sentence as a weaker sentence. Sometimes it’s a better sentence.”

The Supreme Court had taken a similarly thoughtful stance in 2005, when it banned the death penalty for defendants who were younger than eighteen at the time of their crimes. Just as it had found with regard to the mentally disabled, the court held that juveniles had “diminished culpability” for their crimes. Its ruling was based, in part, on science: brain-imaging technology had revealed that the adolescent brain is not fully formed, particularly in the regions that govern impulse control, risk assessment, and moral reasoning. Cole had studied the court’s ruling and others that followed, which established that defendants like Randy were fundamentally different from their adult counterparts. The court would later strike down another penalty for seventeen-year-olds: life without the possibility of parole. Such a harsh sentence, the court noted, did not allow for the possibility of rehabilitation, which was “at odds with a child’s capacity for change.”

Randy had been handed a life sentence with the possibility of parole, which he would be eligible for after serving forty years. But given the heinousness of the crime, there were no guarantees that he would ever be released. “No matter how this plays out, his life is gone,” Cole said. “And I’m not sure anymore what that really accomplishes.” Gail Rich had expressed a similar sentiment after Randy’s trial, saying that a life sentence was too harsh for him.

Cole did not feel the same way about Josh, who was also seventeen years old at the time of the crime. Cole had always believed that Josh, like Curtis, posed a threat to public safety—a view that had only been confirmed in 2002, when the two friends escaped from the Montague County jail while awaiting a transfer back to prison after a court date. They had attacked a guard with a homemade knife and then stolen another guard’s car, leading hundreds of law enforcement officers on a ten-day manhunt. They finally surrendered in Ardmore, Oklahoma, after a six-hour standoff at a convenience store, where they held a man hostage at gunpoint. Their escape marked the first time in Cole’s life that he had armed himself, keeping a .40-caliber pistol with him while they were on the loose.

In 2010 Cole visited with the new DA of Montague County, Jack McGaughey, a dignified, silver-haired prosecutor who had plans to run for district judge. The two lawyers had a long and friendly history, but when Cole tried to argue that Randy deserved a sentence reduction, McGaughey said he was reluctant to support a commutation in such a brutal case. The following year, Horner also won an audience with McGaughey. A warm, upbeat woman, Horner told the DA of her frequent visits to see Randy in prison, where she saw someone transformed. “This is a boy who deserves a chance,” she implored him. “He’s not a violent person. He’s not someone a community would fear. I think he would be a productive citizen. I think he has something to offer this world.” McGaughey listened attentively but was not persuaded. “I am unwilling to recommend this,” he subsequently wrote to her attorney. “After consultation with the Sheriff and District Judge, it is my understanding from them that they are also unwilling to recommend a reduction of sentence.”

Cole had his last drink just a few months later, on November 23, 2011. He had been busy rebuilding his life, marrying Nobile in 2009 and joining the Wise County DA’s office the following year, where he went to work as an assistant prosecutor. He threw himself into his new job, trying every kind of case except for DWIs. From time to time, he thought about Randy.

Though Cole had always been fatalistic about Randy’s chances of getting a commutation, the certainty that he would have to spend decades in prison left the lawyer unsettled. Cole believed that Randy deserved a severe punishment for his crime, but a life sentence seemed like a great waste. Horner had told Cole about her visits to the Allred Unit, the razor-wire-ringed prison where she and her husband, James, were Randy’s only regular visitors besides his mother. The reticent 17-year-old whom Cole remembered had, Horner told him, turned into a reflective, articulate young man. Cole, who was 54, wondered what it would be like to visit him. He wanted to know who Randy had become in prison and what he would say about the murder after all those years.

One blustery North Texas morning last October, Cole found himself sitting at a conference table in a small, unadorned room, waiting to see the now 34-year-old inmate. A guard led Randy in, and Cole watched as he shuffled to his seat, constrained by leg irons. He was startled to see Randy in person. The slim teenager he had sent off to prison was broad-shouldered and muscular, his expression unsentimental. Randy sat down, and the two men looked each other in the eyes.

“It’s been a long time,” Cole said.

“Yes, it has,” Randy replied, sucking in his breath.

Cole assured Randy that he had no agenda and only wanted to have a dialogue. “I really just want to know how you’re doing,” Cole said. Randy, who was aware of the prosecutor’s recent work on his behalf, soon relaxed, and they settled into a comfortable conversation. “I’ve heard thousands of stories about what prison is like, but I don’t really know,” Cole said.

“It’s probably not as bad as they say,” Randy said. “I can’t lie—it was bad when I first got locked up. I had a lot of anger. But it’s just like anything else. You get used to it. I try to stay busy. I go to class twice a week. I obey the rules because it makes my life easier. We have a good chaplain, and he has a lot of programs going on.”

“Good,” Cole said.

“It’s still hard to accept being here, but there comes a point when there’s no use fighting it anymore, no use being hardheaded,” he said. “So you make the best of it.”

Cole nodded. “I was going to say, ‘I know what you mean,’ but I don’t,” he said. “I really don’t. I used to say that to people whose family members had been murdered: ‘I know how you feel.’ I stopped saying that because I don’t really know. It was insincere.”

“Truth is always the best approach,” Randy said. “I found that out.”

“I don’t know that that did you a lot of good,” Cole said with a halfhearted smile.

Randy shook his head. “No, it sure didn’t,” he said.

Cole seemed chastened by this. “Looking back on it now, I can say that I would have done things differently,” he said, shifting his weight in his chair. “I know that doesn’t change anything. I know that doesn’t help you now, but I would have done things differently. You would have gotten some credit for doing the right thing.”

“Can’t go back,” Randy said matter-of-factly.

“That’s the truth,” Cole said. He studied the young man in front of him. “If you could go back, though, what would you do differently?”

“The main thing I regret is not having done something once we got out to the bridge,” Randy said. “I’ve thought about that every day for seventeen years. The self-preservation kicked in, and my only goal was to get out of there. It would have been a whole lot better on everyone if I had tried to do something.”

“You and Curtis told such different stories about what happened out there,” Cole said. “I had to pick a story. I had to decide who I thought was telling the truth, and I made that decision and believe it was the right one. But I’ve always wondered if there was anything you never talked about.”

Randy stopped and thought for a moment. “I can’t think of anything that I’ve ever left out,” he said.

“The one thing I’ve always wondered—” Cole said. “I’ve always wondered if she was completely unaware, once you got to the bridge, what was about to happen.”

“She was passed out.”

“She never woke up and resisted?” Cole asked. “She never begged for her life?”

“No,” Randy said, shaking his head. “Never.”

The two men sat in silence until Randy spoke again. “There’s not a day that goes by that I don’t think about her,” he said. “It happens first thing every morning, when I see my surroundings.”

Cole took this in and was quiet for a moment. “Have you ever heard from Josh?” he finally asked.

“He sent me two or three letters when I first got to prison, back in ’98.”

“Did he ever admit anything to you?”

“Man, would you believe he was trying to get me to help him on his appeal and he offered me a lawyer?”

“Yeah, I would believe that, actually,” Cole said. “I don’t think he or Curtis are doing real well these days.”

“Oh, no, they’re both in seg, as far as I know,” Randy said, referring to “administrative segregation” cells, where inmates who are considered particularly dangerous are relegated to solitary confinement. “Matter of fact, I know Curtis is at Eastham and Josh is at Hughes. Amazing how many people you’ll find here that know people from other units.”

“Do you still hear from Gail?” Cole asked.

“It’s been a long time,” Randy said.

“I think if it had been all up to her, then we might have had something different for you,” Cole said. “Duane—I don’t know that Duane would ever have agreed to a lesser sentence.”

“The man lost his child,” Randy said. “I can’t begin to even comprehend what that might be like.”

“They say it’s the worst kind of pain you can have,” Cole said. “I don’t know, and I hope I never find out.”

Their conversation spanned two hours. They talked about Randy’s life—how he had not had a disciplinary case in more than a decade. How he regularly attended Bible study. How he enjoyed his job mopping floors, which he did late at night, when the cell block was quiet.

“If you got out, what do you think you’d do?” Cole asked.

“If I was to get out right now, I’d be lost,” Randy said. “I don’t have any life skills. I’ve never paid rent or made a regular paycheck. I haven’t driven a car in seventeen years. I’ve never been on the Internet.”

“So you don’t even know what that’s all about,” Cole said, floored.

“Denise tells me about it,” Randy said. “She says she does her banking on her phone.” He shrugged, as if to say he wasn’t quite sure what that meant. “I mean, I’ve developed intellectually, I guess, but not personally.”

“Have you been able to develop any friendships?”

“Oh, yeah, I got a few good friends,” Randy said. “I mean, I live in a dorm with eighty people.”

“Like an army dormitory?” Cole asked.

“We each have a little cubicle—it’s about six feet by ten feet—and a wall about four and a half feet high,” Randy said. “So there’s a little privacy. We have a communal shower and toilets. In my dorm, at the security level I’m at, a lot of people are getting ready to go home. So I watch people make parole and leave. Some of my good friends have left.”

“You’re almost halfway through your sentence?”

“I’m three years from being at the halfway point,” Randy said. “And mentally I think I’ve developed to the point where I can move on. I don’t have any expectations, really. All in all, man, for being locked up for seventeen years and having a whole lot more to go, I’m doing really good. I’ve got some unconventional circumstances here, but it doesn’t have to all be gloomy.”

“Not everyone has that outlook,” Cole said.

“Believe it or not, people come to me for advice,” Randy said. “They know I’ve been in here since I was seventeen and I’ve made it this far, so they come to me. If they’re struggling, I use my experience to try to help them cope. I like to teach people to play chess. You watch them win their first game—huge smile.”

“That’s not an easy game,” Cole said. “I play it with one of my sons.”

“No, it’s not,” Randy agreed. “But the first time he won a game, he smiled, didn’t he?”

Finally, when their time was over, Cole rose from his seat. He was satisfied, or as satisfied as he would ever be, that Randy had been deserving of mercy. He was also struck, once again, by the thought that more than one life had been taken on the Belknap Creek bridge that night.

Randy could not shake Cole’s hand because his own hands were shackled, but he nodded his head in parting. “Thanks for being human,” Randy said. “Thanks for having enough—I don’t know what to call it—personality of your own to come back and say there’s things that you could have done different.”

“I wish you luck,” Cole said.

“Yes, sir,” Randy replied.

“Maybe we’ll see each other again,” Cole said. Then he turned and walked away.

Randy, who will become eligible for parole in 2036, when he is 57 years old, was escorted back to his cell.