This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Even over 300 miles of transatlantic cable a BBC voice is a BBC voice: calm, assured. “You see we’re doing this anniversary thing on the Assassination. We want you to interview Jackie Onassis, Nellie Connally, Lady Bird Johnson, Marina Oswald, Mrs. Tippett, Judge Sara Hughes, and oh, yes, Lee Harvey Oswald’s mother.” A job is only a job. This would be a career! I became excited. “You mean you want me to fly to the Greek islands and . . .” “No. Catch her in Central Park if you can. We’ve got our trace service in New York locating the others.”

The weeks passed. Jackie Onassis did not seem to be in Central Park. The trace service could locate no one. Not even Nellie Connally, even though McCalls had just done a big story on her. The voice from the BBC was turning testy. “No one? Listen. You’ve got to find four women. We’re planning this big feature. The Widows of Dealey Plaza. Go to Dallas. See what you come up with, and watch the expenses. We’re flying this photographer out from London to meet you there.” “You’re flying a photographer out from London, and you ask me to watch the expenses? There are photographers in Texas, you know.” The voice from BBC didn’t believe it.

The photographer came down from New York with me in the end. He was plump and like most pro photographers he liked to talk about sex. We rose above LaGuardia in the wet dawn. The photographer announced he wanted to lay the air hostess. And that girl three rows back. And that other one. We flew over Memphis. Nice girls in Memphis, said the photographer. We landed in Dallas. We checked into the Holiday Inn on Elm St. It was 10:30 A.M. The photographer beckoned to the bell boy. “Where can we get laid in this town?” It looked like a long week.

It got longer. Kenneth Porter, Marina Oswald’s second and present husband, said No. Then he said it again. No. Finally he seemed to be saying that an interview with photographers would cost $3000. The voice from the BBC indicated surprise and shock. “Three thousand dollars. That’s more than a thousand pounds.” “I know.” “So what you’re saying is, no Marina Oswald. Nellie Connally is in San Diego. Lady Bird won’t see you. And Mrs. Tippett, now Mrs. Thomas, won’t return your calls.” “I am saying that.” “So at a cost of about $5000 in expenses and air fares you have interviewed Judge Sara Hughes.” “Yes.”

It seemed time to play my one card. “I’ve got Mrs. Marguerite Oswald. I’m seeing her tomorrow. It’s costing $400, but she’ll be sensational. I’ll do a little round-up on the others, some atmospherics on Dealey Plaza, and you can center it round her.” There was along ruminative silence between room 1827, the Holiday Inn, Dallas and extension 2563, Broadcasting House, London. Finally the great British solution to all tricky problems: “Do the best you can.” The voice added that the pictures better be good. They were going to put Marguerite on the cover. If the pictures were good.

I didn’t tell the voice that Marguerite had specified One Pose, Three Pictures. Anyone who has horsed around watching magazines waste money will know that no picture editor worth his light box is satisfied with less than ten poses and a hundred photographs.

We drove nervously to Fort Worth. Even on the phone Mrs. Marguerite Oswald’s commanding personality had been evident. “You’re being paid to do the story. Your outfit will make money. What about me? I have no money, but I hold the cards. I am the mother of Lee Harvey Oswald. I’ve waited ten long years for this. I always said it would break in ten years. My son is supposed to have been the assassin. Yet he was never tried. He died legally innocent. Unless they prove to me that he killed President Kennedy, this is my opinion. All I want is the truth.”

By and large Marguerite Oswald has not done well out of publicity. Writers have described her as a ghoul. She has said she would like to sell Lee’s gravestone. She is as briskly businesslike about her son’s belongings as a medieval monk selling pieces of the True Cross. She has been married three times. Her second husband divorced her, saying she had knocked him about. Her third husband, Lee’s father, died in 1964. William Manchester, no friend of the simple fact, described “her heavy jaw, knotted neck muscles, and face the colour of burnished pewter.”

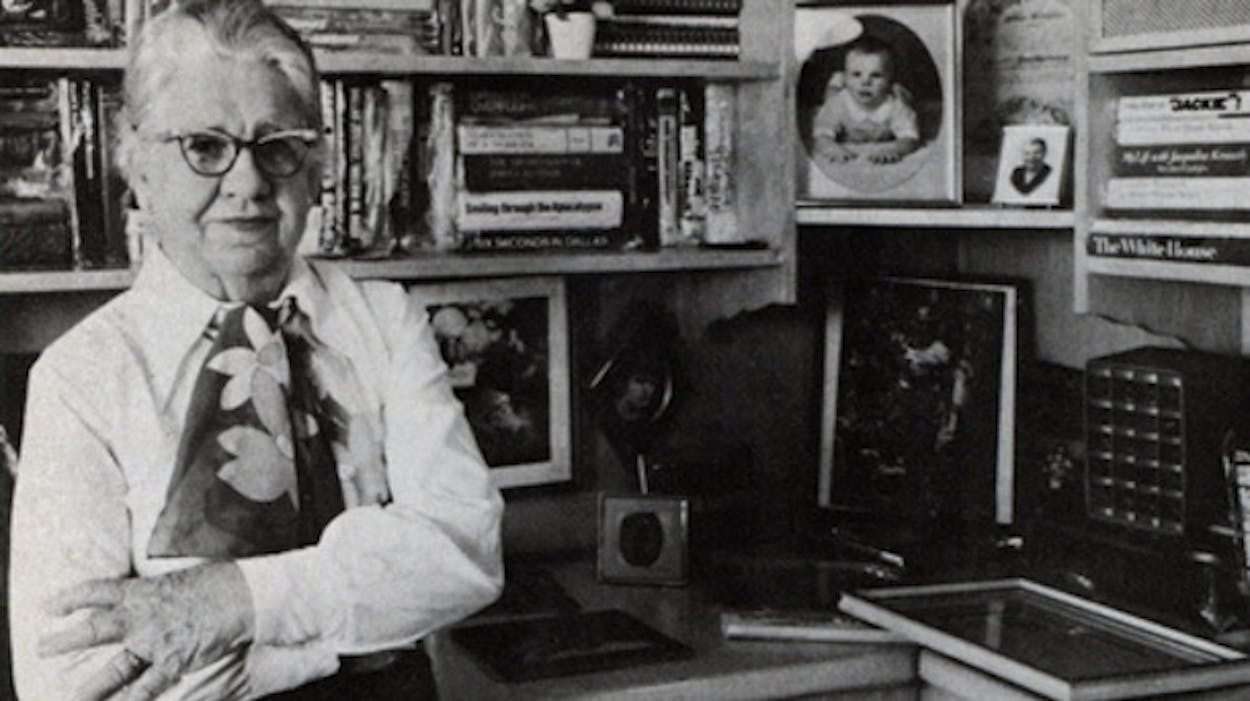

The homely countenance that peered through the door seemed flesh-colored to me. Her eyes do pop a little. Her neck seemed normal. Her house is modest, but pleasant. A little study is crowded with Oswald relics and the bulk of the 350 or so books written on the assassination. Also photos of Lee, and of Marina. A blackboard has chalked on it with deliberate, camera-catching provocation, “They are all making the same mistake.” She lives alone, with two large dogs.

The photographer rose to the occasion. Separated momentarily from access to potential lays he threw himself into his role: the distinguished artist asking “as a privilege” for a few portraits. He sounded like a bishop saying his prayers. He said, truthfully, that he had photographed the Pope. He let her peer through the camera. He erected umbrellas, strobe lights. He clicked and clicked. Sweat poured off him, as Marguerite graciously inclined this way and that. She changed dresses. Still he clicked. I rejoiced. Even the BBC would be satisfied.

Marguerite Oswald speaks with the passion and truculence of a woman with very little money and only one asset. She is the mother of the man many people think shot the President.

“I am the strongest person in this tragedy, because I have lost everything. But Marguerite Oswald fights the powers. She’s the one who speaks out. She believes there has been injustice. This woman [she tapped herself repeatedly] was left with no one and no money. Yet she took the bull by the horns and found a way to survive and support herself. Her attitude is correct, and she will rob Peter to pay Paul occasionally. And Marguerite Oswald has survived.”

From an even tone her voice rose sharply. “I’m going to fix Mrs. Kennedy and the rest of them. The Kennedy family has known the truth, and they let this family suffer. I would like in this interview to say something controversial about the Kennedys. Mrs. Kennedy bothered me. She was . . . in front of me . . . no, that’s not descriptive enough . . . it was as though she was there in person.”

“Like a ghost? Or was this a dream ?”

“No, I never dream. She was always on my mind, even though I had lots of work to do. When she remarried she disappeared entirely.”

We moved from the study to the sitting room, where Mrs. Oswald has hung a reproduction of “Whistler’s Mother.” I asked her if she was persecuted. “I must be careful. They want me to say I’m persecuted, so that they can say I’m a psycho, and that I only think I’m persecuted. This is what they do to me. The neighbors don’t invite me in for coffee, even though I’ve had them in my house. But I’ve waited. I’ve waited ten long years and it’s ready to break now. All I’m waiting for is the chance, the offer, to do my book.

“It’s all in my book. Ten years everyone said Lee was a Communist, a defector. That’s all changed now. If it had been a church man, or a politician of well known integrity would you have jumped to the conclusion that you had the right man. No, no, I said. It was only because he allegedly defected that they said he was the assassin. It took three years for the picture to change, for the critics to get into the Volumes.”

The “Volumes” are the Warren Commission findings, which Mrs. Oswald has ever ready to hand. “Imagine paying for this trash.” She seized a volume and started reading contradictory statements out of it. Her voice grew harsh and very loud.

“They’re all scum. I know what they have, and if I know all this I know I can survive. They framed him so good, but I’ll fix them in my book. That sustains me. I cry a lot. I can hardly pick up the 26 volumes without crying.”

She read some more and as she read, tears trickled down from under her spectacles. Then she said in a rasping cry, “If I know all this I can survive. I never see my grandchildren. I want to go away . . . to write my book . . . I want to be free . . . I’m alive, I’d like to get out. I’m stuck here with no money and no friends. My life’s not over. I’d like to disappear. Ten years has gone out of my life. I need to be taken out to dinner and dance. I’m not dead yet. I’m only 66. But I need the capital, and I hold the cards. Maybe a European publisher would like my book, so I could get away and be free.”

For a moment, in the little house on the edge of Fort Worth, it seemed that we were interviewing Emma Bovary, the passion so strong: so bitter the tears. The photographer sweated thoughtfully in a corner, and then to lighten the fraught atmosphere we suggested some exterior pictures. Mrs. Oswald brightened. “The neighbors won’t like it. But what the hell. I like you boys. I’ll put on my disguise, like when I go out researching. My Jackie Kennedy disguise, with the headscarf.”

She posed. He clicked. Then we made our goodbyes. “You see, I am the strongest,” she said as we left. “I have nothing and I survive. Be sure and tell publishers I have the book. And I know. Because I am the mother of the man they say shot the President.”

“She was terrific,” I shouted down the line to the voice. “Worth a whole feature. Put her on the cover. Call it “Mother of the Decade.” The BBC voice brooded for a moment. Then it brightened. “Well, you’ve done your best, haven’t you?”