There are things about women that most men would just as soon never discuss. The stirrups in a gynecologist’s office, for one; the tampon aisle at the grocery store, for another; and pretty much any matter involving words like “cervix,” “uterus,” and “vagina.” At least, that’s how it was until March 2, 2011. Back in January of the same year, at the start of that legislative session, Governor Rick Perry had pushed as an emergency item a bill requiring all women seeking an abortion to have an ultrasound 24 hours beforehand. As Sid Miller, the legislator who sponsored the bill in the House, put it, “We want to make sure she knows what she is doing.”

At a public hearing on the bill the following month, Tyler representative Leo Berman took the mike and insisted that 55 million fetuses had been aborted since Roe v. Wade—or, as he called it, “a Holocaust times nine.” The author of a book on abortion rights gave a somewhat overwrought speech about the differences between “a zygote and a baby.” A woman named Darlene Harken described herself as “a victim of abortion” because, she maintained, she wasn’t warned about the mental and physical fallout from the procedure; Patricia Harless, a representative from Spring, thanked her for her “bravery” and “strength.” Alpine’s Pete Gallego countered by expressing his resentment of “people who stop caring after the child is born.”

In March the bill reached the House floor, where debate raged for three days, as much as ten hours a day. Tensions ran high in the chamber, which was lit by a benevolent winter sun that glinted off the manly oak desks and supersized leather chairs. On the first day, March 2, Miller, a burly man with white hair and a sun-lined face that wrinkles into a bright, inviting smile, explained the legislation. A former school board member from Stephenville, he has a loamy Texas accent and favors a spotless white Stetson. If you stare at him long enough, you might easily forget that it’s the twenty-first century.

As Sid Miller, the legislator who sponsored the bill in the House, put it, “We want to make sure she knows what she is doing.”

Miller described his bill in a matter-of-fact tone, as if he were pushing a new municipal utility district. “What we’re attempting to do is to provide women all available information while considering abortion and allow them adequate time to digest this information and review the sonogram and carefully weigh the impact of this life-changing decision,” he began. Miller then listed everything his bill would require before an abortion could be performed. A woman would have to review with her doctor the printed materials required under the 2003 Woman’s Right to Know Act. While the sonogram image was displayed live on a screen, the doctor would have to “make audible the heartbeat, if it’s present, to the woman.” There was also a script to recite, about the location of the head, hands, and heart. Affidavits swearing that all of this had been properly carried out according to Texas law would have to be signed and filed away in case of audits. A doctor who refused could lose his or her license.

As soon as Miller finished, Houston Representative Carol Alvarado strode up to the podium. There could have been no clearer contrast: her pink knit suit evoked all those Houston ladies who lunch, its black piping setting off her raven hair. Her lipstick was a cheery shade of fuchsia, but her disgust was of the I-thought-we’d-settled-this-in-the-seventies variety.

“I do not believe that we fully understand the level of government intrusion this bill advocates,” she said tersely. The type of ultrasound necessary for women who are less than eight weeks pregnant is, she explained, “a transvaginal sonogram.”

Abruptly, many of the mostly male legislators turned their attention to a fascinating squiggle pattern on the carpet, and for a rare moment, the few female legislators on the floor commanded the debate. Representative Ana Hernandez Luna approached the back mike and sweetly asked Alvarado to explain what would happen to a woman undergoing a transvaginal sonogram.

“Well,” Alvarado answered helpfully, “she would be asked by the sonographer to undress completely from the waist down and asked to lie on the exam table and cover herself with a light paper sheet. She would then put her feet in stirrups, so that her legs are spread at a very wide angle, and asked to scoot down the table so that the pelvis is just under the edge.”

At this point, if there had been thought bubbles floating over the heads of the male legislators, they almost certainly would have been filled with expletives of embarrassment or further commentary on the carpet design.

“What does this vaginal sonogram look like?” Luna asked, ever curious.

“Well, I’m glad you asked,” Alvarado answered, “because instead of just describing it, I can show you.”

And so the state representative from Houston’s District 145 put both elbows on the lecturn and held up in her clenched fist a long, narrow plastic probe with a tiny wheel at its tip. It looked like some futuristic instrument of torture. “This is the transvaginal probe,” Alvarado explained, pointing it at her colleagues as she spoke, her finger on what looked like a trigger. “Colleagues, this is what we’re talking about. . . . This is government intrusion at its best. We’ve reached a”—she searched for the word—“climax in government intrusion.”

Those who could still focus gaped at Alvarado. No one spoke. The silence seemed to confirm for Alvarado something she had long suspected: most of the men in the House chamber didn’t know the difference between a typical ultrasound—the kind where a technician presses a wand against a pregnant belly and sends the happy couple home with a photo for their fridge—and this. She locked Miller in her sights. “What would a woman undergo in your bill?” she asked.

Miller seemed confused. “It could be an ultrasound, it could be a sonogram,” he began. “Actually, I have never had a sonogram done on me, so I’m not familiar with the exact procedure—on the medical procedure, how that proceeds.”

“There are two different kinds of sonograms,” Alvarado said, trying again to explain. “The abdominal, which most of our colleagues may think [of as] ‘jelly on the belly’—that is not what would be done here. A woman that is eight to ten weeks pregnant would have a transvaginal procedure.” Miller stammered a response, but Alvarado was not done with him. She continued the grilling for several more minutes, keeping Miller on the ropes with a sustained barrage of icky female anatomy talk. Ultimately, however, the room was stacked against her.

On March 7 Miller’s bill passed 107–42.

Over the next few months, as the Senate passed its version of the bill, which was sponsored by Houston senator Dan Patrick, and as Governor Perry signed the legislation into law at a solemnly triumphant ceremony, the exchange between Alvarado and Miller stood as a glaring reminder of the peculiar way in which women could be largely boxed out of decisions that were primarily concerning them. (A number of female Republican legislators supported the bill too, but the overwhelming majority of the votes cast in its favor were from men.) Of course, women have rarely held the reins of power in Texas, but there has also seldom been a season as combative on the subject of women’s health as the one we have experienced in the past eighteen months.

Miller’s bill was only the beginning of what turned out to be the most aggressively anti-abortion and anti-contraception session in history. In the words of one female reporter who covered the Legislature, “It was brutal.” Not only did the sonogram law pass, but drastic cuts were made to statewide family planning funds, and a Medicaid fund known as the Women’s Health Program was sent back to Washington, stamped with a big “No thanks.” When the dust settled, Texas had turned down a $9-to-$1 match of federal dollars, and the health care of 280,000 women had been placed in jeopardy. And that wasn’t all. Earlier this year, around the time that the new laws began to take effect, an epic, if short-lived, fight broke out between Planned Parenthood and the Susan G. Komen Foundation, pitting two of Texas’s most powerful women against each other and highlighting the agonizing, divisive nature of the debate over women’s health. No sooner had this conflict subsided than the Legislature’s decision to kill the Women’s Health Program was dragged into the courts for a series of reversals and counter-reversals that is still not resolved.

These conflicts could all be seen as the latest in a long struggle, as women in Texas try to gain control over not just their own health care decisions but their own economic futures and those of their families. This is the state, after all, from which the modern abortion wars originated in 1973 with Roe v. Wade, a case, let’s not forget, that pitted a 21-year-old Houston woman and two upstart lady lawyers from Austin against formidable Dallas County district attorney Henry Wade. It’s a decades-old battle between the sexes over who knows best and, more importantly, who’s in charge. And over the past year, the fighting has intensified. On the one side are the Carol Alvarados of the world; on the other, the Sid Millers. The outcome will determine nothing less than the fate of Texas itself.

For most of Texas history, even during the seemingly halcyon period that was Ann Richards’s governorship, the goal of Texas women to achieve parity with Texas men has been out of reach. The men who settled the state were a tough bunch. They had to survive a harsh, unforgiving climate; murderous Comanche; soil that was in many places relentlessly resistant to cultivation; rattlesnakes; bandits; long, lonely cattle drives; and more. But women—to paraphrase Richards—had to do most of that barefoot and pregnant and without any of the liberties or rights that men enjoyed. As the saying goes, “Texas is heaven for men and dogs, but it’s hell for women and horses.”

Many frontier women learned quickly that they were effectively on their own—the downside to hooking up with a rugged individualist far more comfortable with his cattle than with his wife. They bore, raised, and, too often, buried their kids. They figured out how to make do in the face of cruel poverty. Women had to contend with a challenging contradiction: on the one hand, the clearly defined sex roles of the nineteenth century dictated a courtliness and paternal protectiveness on the part of Texas men that survives to this day. On the other hand, the state was settled in most cases by force, fostering a worship of physical strength and a visceral contempt for anyone too weak to make it on his or her own.

Modern Texas history is filled with stories of women who were held down by what academics like to call “the patriarchy” and the rest of us might simply call “macho white guys.” When trailblazing federal judge and legislator Sarah Hughes ran for reelection to the House in 1932, for instance, her opponent suggested that her colleagues “oughta slap her face and send her back to the kitchen.”

Governor John Connally’s Commission on the Status of Women, established in 1967, found numerous inequities in education and the workforce—but also noted that “overly enthusiastic soapboxing oratory can do the feminine cause more harm than good.” It has been frequently pointed out that Kay Bailey Hutchison, one of the most successful females in recent Texas history, became a television reporter in the sixties because, after finishing law school, she couldn’t find work as an attorney. During Barbara Jordan’s entire term in the Legislature, which lasted from 1967 to 1973, she was the only woman in the Senate; across the hall, there was only one female in the House: Sue Hairgrove, followed by Sissy Farenthold.

What their male counterparts seemed slow to grasp was that, having endured the same adverse frontier environment as their husbands, fathers, and brothers, Texas women developed many of the same characteristics: the indomitable independent streak, the persistent optimism in the face of lousy odds. But instead of speculating in cotton or oil or real estate, women focused on sneaking power from men.

The pseudonymous Pauline Periwinkle campaigned for improved food inspections in 1905 by suggesting that a woman lobby her otherwise uninterested husband after he “has broken open one of those flaky biscuits for which your cuisine is justly famous.” During the Depression, when contraceptives were among the obscene materials the Comstock law deemed illegal to send through the mail, one Kate Ripley, from Dallas, used boxes from her husband’s shirt company to disguise the contents of illicit packages that she shipped to women all over Texas.

As the twentieth century advanced and women began to win seats at more influential tables, several distinct types emerged. For many years, before it was considered politically incorrect, a woman in the political arena was known as a good ol’ girl or a man’s woman. This complimentary description meant she could drink, cuss, and cut a deal and probably never cried in public. Many of these women were what today we’d call liberals, people like Jordan, Farenthold, Sarah Weddington, Richards, and Molly Ivins. They may have endured the hollow loneliness of public scorn, but they managed to get the Equal Rights Amendment ratified in Texas in 1972. It’s probably no accident that these particular heroines came from the liberal tradition—it’s the one that has been most likely to let women talk, even if they weren’t always heard.

But conservative women made their presence felt as well. The most successful ones, like Hutchison or Harriet Miers, played an inside game, making nice—or at least appearing to make nice—while quietly accumulating power. Beauty helped, especially when combined with a rich husband, as Joanne Herring has demonstrated. Barbara Bush took a page from sturdy Republican club women and made herself a common-sense heroine in low heels and pearls. In other words, there were various ways to get around men and grab the steering wheel, and over the years Texas women used them all.

Regardless of their politics, both Democratic and Republican women used their power to advance the cause of family planning. During the time when abortion was both dangerous and illegal—before 1973—volunteering for Planned Parenthood was a socially acceptable, even admirable, thing for many middle- and upper-middle-class women to do. It isn’t surprising that Farenthold and Richards were big family planning advocates, but so were the very social Sakowitz and Marcus families, the arch-conservative Hunt family, and George and Barbara Bush (at least until he joined the anti-abortion Reagan team in 1980). Partisanship just wasn’t in the picture.

“Over the years, everyone wrote a check,” said Peggy Romberg, who worked for Planned Parenthood in Austin for seventeen years. The issues seemed very different in the sixties and seventies: women had husbands who made them remove their IUDs, or who made them quit school to tend to their babies. A woman’s sexual history was allowed to be admitted in court during rape cases. Married women who wanted credit cards in their own name needed their husbands to cosign for them.

Then came that landmark moment in the history of women all over the U.S. The story of Roe v. Wade is, in many ways, the story of Texas women. Norma McCorvey (a.k.a. Jane Roe), raised in poverty in Houston, a high school dropout at fourteen, beaten by her husband, and pregnant with her third child in 1969, tried first to lie in order to get a legal abortion—she claimed she had been raped, which would have permitted the procedure in Texas—and then she tried to get an illegal abortion, but her clinic of choice had been shut down by the authorities. Eventually, two Austin attorneys, Weddington and Linda Coffee, filed suit on her behalf, arguing that her right to privacy included her right to have an abortion. (A San Antonio oil heiress, Ruth McLean Bowers, underwrote the legal costs of the case.) In 1973 the U.S. Supreme Court agreed that state laws banning abortion were unconstitutional. The vote was 7–2.

The story of Roe v. Wade is, in many ways, the story of Texas women.

Nearly forty years of legal abortion have followed, along with an endless stream of bitter arguments and toxic political strife. McCorvey, who wound up having her baby as the case progressed through the courts, later did an about-face, becoming an activist with the pro-life group Operation Rescue. Weddington went on to become an icon of the women’s movement. In time, the case they launched emerged as one of the most divisive and politically expedient issues in American politics. Maneuvering from the Governor’s Mansion to the White House, George W. Bush used it to successfully solidify conservative Republicans around his candidacy. Though Bush said he was against overturning Roe v. Wade, he talked about promoting a “culture of life,” signed the Abortion Ban Act, in 2003, and campaigned vigorously on the issue, using it to draw a sharp distinction between himself and both Al Gore and John Kerry.

In Texas the past decade has seen a sharp turn in the rhetoric of the issue. Some of it is the result of the ferocious GOP primary wars that are now a fixture in what has essentially become a one-party state. Since there is only one election that matters anymore, it has tended to become a contest over who can move furthest to the right. Being labeled a RINO—a “Republican in Name Only”—is a fate worse than death, and what better way to establish one’s conservative bona fides than by passing laws limiting abortion?

A parental notification law for minors seeking abortions passed in 1999 (later, legislators passed a law requiring that minors get permission from their parents before getting the procedure). The 2003 Woman’s Right to Know Act, sponsored by Representative Frank Corte, of San Antonio, required doctors to give pregnant women a booklet—tinted pink with a daisy on the cover—that includes information about the growth and development of “the unborn child” and color photos of the fetus from 4 to 38 weeks of gestation. (This booklet is also infamous for erroneously linking abortion with difficulties during future pregnancies and higher rates of breast cancer.)

By far the most important change came as a result of a 2005 lawsuit called Planned Parenthood of Houston and Southeast Texas v. Sanchez, which required the separation of all family planning facilities into two entities: one would distribute birth control and perform women’s wellness checkups and cancer screenings, while the other would provide abortions exclusively. Government audits were mandated annually to make sure that no state money—no tax dollars—could ever be used to fund abortions.

“I think we all thought this was harassment—it wasn’t going to improve public health. But we said okay, we’ll get through this too,” said Peter Durkin, who was the president and CEO of Planned Parenthood Gulf Coast for 27 years. Still, despite all the conflict over abortion, there remained some restraint in the Legislature over family planning. It was a given that reasonable people could differ over abortion, but most lawmakers believed that funding birth control programs was just good policy; not only did it reduce the number of abortions, but it reduced the burden on the state to care for more children.

The result, in Texas and beyond, was a full-scale assault on the existing system of women’s health care, with a bull’s-eye on the back of Planned Parenthood, the major provider of both abortions and family planning in Texas and the country.

That changed dramatically after 2010, when Republicans won 25 seats in the House, giving them a supermajority of 101 to 49 and total control over the law-making process. (The male-female split is 118 men to 32 women.) As the Eighty-second Legislature began, a freshman class of right-wing legislators arrived in Austin, determined to cut government spending—a.k.a. “waste”—and push a deeply conservative social agenda. At the same time, Governor Perry was preparing to launch his presidential bid, burnishing his résumé for a national conservative audience. It wasn’t a good time to be a Democrat, but it wasn’t a great time to be a moderate Republican either. Conservative organizations turned out to be as skilled at social media as your average sixteen-year-old, using Twitter and Facebook to chronicle and broadcast every move of the supposed RINOs. A climate of fear descended on the Capitol. “Most people in the House think we should allow poor women to have Pap smears and prenatal care and contraception,” an aide to a top House Republican told me. “But they are worried about primary opponents.”

The result, in Texas and beyond, was a full-scale assault on the existing system of women’s health care, with a bull’s-eye on the back of Planned Parenthood, the major provider of both abortions and family planning in Texas and the country. As Representative Wayne Christian told the Texas Tribune, in May 2011, “Of course it’s a war on birth control, abortion, everything. That’s what family planning is supposed to be about.”

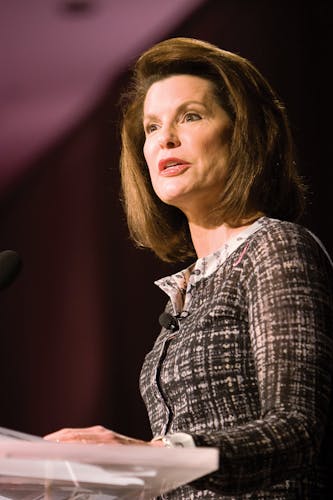

For those with institutional memory, the most striking thing about Cecile Richards is how unlike her mother she is. The president of the Planned Parenthood Action Fund possesses none of the folksiness and none of the bite that helped make Ann Richards an icon, maybe because neither quality is really necessary or useful anymore (and could actually be considered a hindrance for the head of a national women’s organization in 2012). In fact, on the rainy day I met with Richards at Planned Parenthood’s headquarters in Manhattan, she looked like someone who had come into her own. Long gone was the awkward perm she once sported. Tall and willowy, she wore a deep-purple sheath with matching peep-toe heels, a combination of chic understatement with just a hint of flash.

Clearly, she had learned her political skills not just from her mother but also from her father, labor lawyer David Richards. Before coming to Planned Parenthood, in 2006, Cecile was a labor organizer and the founder of two progressive groups: America Votes, a nonprofit designed to promote liberal causes, and the Texas Freedom Network, an organization designed to combat the Christian Right. In other words, to Planned Parenthood’s opposition, she’s the Antichrist.

Richards long ago learned to modulate her anger for public consumption. But when she gets to talking, she can be extremely frank. “The equity that women have now in education and wages is because of family planning,” she told me, leaning forward, her voice hardening just a little. “For women, it’s not a social issue. It’s not political. It’s fundamental—fundamental to their economic well-being.” She went on, seemingly unable to believe that she was being forced to restate the obvious: birth control enables women to stay in school instead of dropping out, and to get a degree that boosts their economic status for life. It allows them to control the size of their families so that they can afford the kinds of futures they envision for themselves and for their children. A woman who once had five kids might now only have two—and send them both to college. And so on.

But why, I asked, should taxpayers be on the hook to pay for it?

“Why should we pay for Viagra?” she responded. “Why should men be treated differently? We pay for all other medications. Birth control is the most normative prescription in America. Ninety-nine percent of women use birth control. It’s 2012, for God’s sake!”

As for the changes in Texas, she was deeply disappointed. She had worked on the border with women who have since lost access to cancer screenings. She didn’t think Governor Perry was taking the majority of Texans where they wanted to go. “It’s hard to go back home,” she told me. “That heartlessness does not track with the Texas I grew up in.”

Indeed, in the Texas of Richards’s youth (she was born in 1958), lieutenant governors like Bill Hobby and Bob Bullock worked with Planned Parenthood to set up a network of clinics all over Texas, in both small towns and big cities. Texas Health and Human Services offered funding through a federal grant for communities willing to open new clinics for the underserved, and Planned Parenthood provided everything from breast and cervical cancer screenings to abortions. “We were encouraged to open new locations,” Durkin recalled, “and the state sat right next to us when the extremist furor erupted—and it always died down.”

One reason for the tolerance, Durkin said, was that 25 years ago there was a greater tendency to “keep out of a lady’s business.” “In the good old days,” he explained, “the Texas Department of Health was managed by retired military doctors who focused more on afternoon golf than reproductive health care issues. And the governor’s office didn’t interfere either.”

The expansion of family planning was crucial to the general health and future of the state itself. Texas has the second-highest birthrate in the nation, behind California. Historically, it has also had one of the highest rates of uninsured women in the country. Today, more than half the babies born each year are to mothers on Medicaid. Since the cost differential between a Medicaid birth plus postnatal care and a year of birth control pills is huge (around $16,000 for the former versus $350 for the latter), the notion that publicly funded birth control was good public policy had never been a subject of debate in the past. Prior to the last legislative session, the state’s family planning program was serving close to 130,000 clients who had no form of health insurance, the poorest of the poor. And according to the nonpartisan Legislative Budget Board, the state’s investment in family planning saved $21 million a year by averting more pregnancies. Ironically, before the last session began the LBB advocated for more money to be spent on family planning in order to save on the cost of pregnancies and births, which last year totaled $2.7 billion.

But that’s not exactly what happened.

We’re going to be making bad decisions all day.” It was the morning of April Fool’s 2011, a day of important debate in the House over HB 1, the budget bill, and Wayne Christian was just getting started. Christian, from Center, is one of the more ebullient House members, and despite his grim prediction, his mood seemed upbeat. He knew that, thanks to his party’s supermajority, power would continue to rest in the heart of the Republican caucus, a place he felt very much at home. A past president of the Texas Conservative Coalition and a successful gospel singer, Christian qualified as a true believer, and on this day he was calm. He was, after all, a man with a plan.

The plan had emerged from several years of strategizing by Texas pro-life groups, and it had as its central goal the demise of Planned Parenthood. To those who oppose abortion, the separation of health care clinics and abortion clinics that the Legislature mandated in 2005 had not gone far enough. Even though organizations like Planned Parenthood are audited annually by the state to ensure that no taxpayer dollars go to pay for abortions, this arrangement remains suspect to pro-lifers.

“The separation agreement is not really enforceable,” said Elizabeth Graham, an attractive, sharp-tongued brunette who is the director of Texas Right to Life. “The Legislature has never been comfortable with giving money to 1200 Main Street and 1201 Main Street isn’t getting that money. The funds are fungible.” So Graham’s organization had been working with legislators like Christian, diligently preparing, waiting for the right opportunity. It had finally come. The tactic was to eviscerate Planned Parenthood through the family planning budget. Lawmakers, Graham later told me, “were prepared and understood where funds could go. They had assistance from agencies and information that helped them to redirect funds.”

House Republicans also had a clever procedural maneuver up their sleeves. Ordinarily, budget amendments are vetted by the Appropriations Committee, which may hold public hearings on controversial issues. This time, however, the GOP legislators kept mum, intending to present these amendments from the floor, circumventing the traditional vetting process. (Unlike his iron-fisted predecessor, Tom Craddick, current House Speaker Joe Straus has proved less inclined to prevent such tactics.) This meant the amendments would come with no advice from Appropriations, so members were left without guidelines on how to vote.

Indeed, on April 1, when the family planning section of the budget came up for review, conservative legislators began attaching a blizzard of new amendments, each one designed to shrink the size of the $111.5 million budget from which Planned Parenthood drew support. First up was Representative Randy Weber, who wanted to move $7.3 million out of family planning and allocate it to an organization that seeks alternatives to abortion.

In support of his amendment, Weber, a conservative Republican from Pearland, cited a journal article from 2002 that asserted that in addition to contraception not eliminating pregnancies, it also correlated to a higher rate of pregnancy among women who use it. (In fact, the article stated the opposite.) Representative Mike Villarreal, a Democrat from San Antonio, asked Weber if he thought that birth control simply didn’t work.

“Not for those that get pregnant,” Weber quipped.

“Have you ever used contraceptives yourself?” Villarreal shot back.

“Well, you know, I don’t think I know you well enough to go down this road,” Weber cracked.

Villarreal shifted tactics, insisting that Weber’s plan would do nothing to reduce abortions. Further, if they did what Weber asked, members would be moving money from programs that would save the state around $60 million into one that would not save it a cent.

Weber’s amendment passed 100–44. Next up was Christian, who proposed an amendment that would move $6.6 million from family planning into a program to help autistic children. After consideration of additional proposals, Christian’s amendment passed 106–34. Two more Republican representatives came forward and laid out amendments to move $20 million into early-childhood intervention programs and the Texas Department of Aging and Disability Services. Those passed too. Representative Bill Zedler asked to move funding from “the abortion industry” to services for the deaf and blind and those with mobile disabilities. Representative Jim Murphy wanted to move money to EMS and trauma care, which was operating with a $450 million surplus at the time. Representative Warren Chisum followed with an amendment to move family planning money to more-generalized medical clinics.

As the night wore on, tempers flared; sometimes it was hard to hear over the members’ shouting at one another. Even a staunch Republican like Beverly Woolley found herself moving to the microphone in solidarity with the Democrats. But on and on it went. By one in the morning, the House had slashed the family planning budget from $111.5 million to $37.9 million. The final vote passed with 104 ayes. On May 3, the Senate passed its budget, with the same cuts in place—partly because House Republicans had threatened to hold up the entire budget process if they did not.

By this point, the tenor of the session was clear. As the chair of the Senate Democratic Caucus Leticia Van de Putte said, “Texas is going to shrink government until it fits in a woman’s uterus.” A little over a month later the sonogram bill went to the governor’s desk. “This will be one of the strongest sonogram bills in the nation,” declared an exultant Sid Miller. “This is a great day for women’s health. This is a great day for Texas,” said Dan Patrick, who had tried twice before to get such a bill passed.

Needless to say, not everyone agreed. “I went to an event with Senator [Kevin] Eltife,” Patrick told me some months later, “and I parked and a car pulled up behind me and a woman started screaming at me. I’ve never had that happen. I’ve had some interesting emails too. Just amazing. But I’m a big guy. I can take criticism, because this is the right thing to do to save a life.”

By his account, over time the sonogram bill will save up to 15,000 lives. “There will be people alive in ten to twenty years who wouldn’t be alive without this bill,” he told me. To Patrick, the legally mandated ultrasound isn’t an invasive procedure. Critics of the bill further contend that its ultimate purpose is to limit access to abortion, especially for low-income women who may not be able to take off more than one day of work to accommodate the 24-hour waiting period. Patrick rejects this argument too. As he puts it, “The purpose in sponsoring this bill was to improve women’s health care.” His political opponents, he says, “don’t know the facts. They are dealing from emotion.” He thinks the claim that most women have made up their minds long before they reach the door of an abortion clinic is “nonsense.”

“Most of these women don’t know,” he said. “No one is trying to embarrass them, but we are trying to save a life. You want the woman to have a choice to have a baby or not, but you don’t want them to have a choice to look at a sonogram? That makes no sense to me.” (In fact, prior to the sonogram bill, women seeking an abortion at Planned Parenthood could elect to look at a sonogram.)

As the session reached its halfway point, many female legislators grappled with the magnitude of what had happened. Democratic women could at least enjoy the full-throated support of their male colleagues, but moderate Republican women frequently found themselves all alone, treated to a front-row seat from which to view their own powerlessness. To speak up was to be targeted for defeat in the next primary, after all. They dragged through the Capitol with heads down, making apologies to staffers and colleagues for their votes. Ultimately, both Beverly Woolley and Florence Shapiro announced their retirements. The latter told a lobbyist, “These are no longer the people who elected me.”

Shapiro and Woolley weren’t the only veteran Republicans to find themselves in an awkward position. Take the case of Robert Deuell and the Women’s Health Program. Senator Deuell, a physician from Greenville who has held office since 2003, was known to be both pragmatic and conservative when it came to public health. He supported programs like needle exchange for addicts, but he was strongly opposed to abortion. In fact, he had worked tirelessly since 2007 to toss Planned Parenthood from the network of providers included in the Women’s Health Program, a Medicaid fund for poor women started in Texas in 2006. Yet unlike many of his new comrades-in-arms, Deuell favored taxpayer-supported birth control.

If the state doesn’t make birth control available, he told me, “we are going to be providing prenatal care. It’s the lesser of two undesirables, and that’s the point I’ve tried to make. Do I wish women waited? Yes, but they don’t.”

Deuell has always favored shifting the services provided through the WHP from Planned Parenthood to community-based health organizations and clinics known as Federally Qualified Health Centers. There were some obstacles to this, among them the question of whether the FQHCs could deliver the same quality of care. Many FQHCs were already overrun with very sick people. Jose Camacho, the head of the Texas Association of Community Health Centers, which oversees FQHCs in Texas, had insisted that, despite what Deuell wished, the FQHCs could not absorb the overflow, given Texas’s soaring birth and poverty rates along with the vast number of uninsured. “We served one million patients this year, at least,” he told me. “To think that any health system can ramp up to take, in effect, twenty percent more patients is not realistic.”

Deuell didn’t give up. The rules of the WHP had been written to exclude providers affiliated with organizations that perform abortions. This was in conflict with federal law, so in 2008, a waiver was granted that allowed Planned Parenthood to participate. In 2010 Deuell asked Attorney General Greg Abbott, who also fervently opposes abortion, to check on the constitutionality of the waiver, and when the Eighty-second Legislature rolled around, Deuell was prepared with a rider to the budget bill that would reauthorize the WHP while explicitly preventing Planned Parenthood from ever taking part in it. But by May, he had a problem. He could see a disaster looming—the health care of 130,000 women was already at risk because of cuts to the state’s family planning budget, and now, as a result of the political climate, he saw that he didn’t have the votes in the Senate to get his version of the WHP reauthorized.

“I guess what took me by the most surprise was an overall opposition to family planning,” Deuell told me. The fact that such programs were statistically proven to save money by the Legislative Budget Board was not enough to change hearts and minds, even in a budget-slashing session. “My feeling is that [‘the program will save money’] is what you hear every time they want to increase the size of government,” said Representative Kelly Hancock, the policy chairman of the Republican caucus. He added that the caucus’s opposition to such programs “had nothing to do with the women’s health issue.”

With time running out, Deuell found himself in the surreal position of joining forces with ultraliberal Garnet Coleman, who was trying to push a bill to save the Women’s Health Program in the House. (Back in 2001, it was Coleman, the son of a prominent Houston doctor, who first carried legislation to create the WHP, which Governor Perry vetoed.) This did not go over well, especially with the folks at Texas Right to Life. After a particularly nasty budget committee hearing, Elizabeth Graham compared Deuell to Margaret Sanger, the founder of Planned Parenthood.

Finally, the bill was saved at the end of May by some last-minute politicking—it was attached as an eleventh-hour budget rider. But the victory for women was a hollow one: Planned Parenthood was no longer allowed to participate. It promptly filed suit, as many who had kept their frightened silence in the Legislature had hoped it would. By then, nearly 300,000 Texas women were facing the loss of birth control, wellness checkups, and cancer screenings.

And Deuell, for his part, was still stinging from Elizabeth Graham’s attack. “For her to compare me to Margaret Sanger,” he told me, “it’s beyond the pale.”

This past January, one year after the start of the Eighty-second Legislature, the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the sonogram bill was legal and could stand. (The opinion was written by Edith Jones, a female judge from Texas who has never made her opposition to abortion a secret.) Many women in Texas who had perhaps not been closely following the moves of the Legislature were now discovering the fruits of their representatives’ labors. Others were beginning to realize that, because of the cuts to health care, they couldn’t even get in to see a doctor for annual pelvic exams. Clinics were already closing, or cutting hours, or charging fees for services that had previously been covered.

The session had made it clear that Republican legislators and pro-life groups were intensifying their fight against Planned Parenthood, not just in Texas but across the country. If there was anyone who still didn’t get it, the news of January 31 made it impossible to miss. That was the day that the Associated Press reported that Susan G. Komen for the Cure, originator of the pink ribbon, had decided to cancel the $700,000 annual grant it had been contributing to Planned Parenthood since 2005 for breast cancer screenings. (None of Komen’s money ever went to abortion services.)

The news erupted nationwide, but in Texas it detonated like an atomic bomb. Komen, after all, was based in Dallas and was worshipped there in almost cultlike fashion. What’s more, the organization’s founder, Nancy Brinker, was a role model for many Texas women, a radical reformer who back in the early eighties had, as one of her oldest friends put it, “brought breast cancer out of the closet.” Before she took on the cause, promising her dying sister in 1982 she’d find a cure, most people wouldn’t even say the word “breast,” much less “breast cancer,” in polite conversation. Brinker, a former PR woman originally from Peoria, Illinois, who had married well, to the late Dallas restaurateur Norman Brinker, built Komen into a $1.9 billion philanthropic powerhouse in a relentless, but very feminine, way. She was also a highly visible moderate Republican woman, and a friend of George and Laura’s who was rewarded with an ambassadorship to Hungary in 2001 and a position as White House chief of protocol in 2007.

What happened, in brief, was this: anti-abortion groups had been harassing Komen (and the Girl Scouts of America and Walmart) for years over its support of Planned Parenthood. A very vocal, if small, faction was alarming affiliates with threats to disrupt the footraces that have long been Komen’s major source of funds. John Hammarley, Komen’s senior communications adviser, found himself fielding more and more phone and email inquiries about the relationship between the two organizations. “It took up a sizable amount of my time,” he told me.

A few years earlier, Brinker, who is 65, began to step away from running the organization. She brought in a new president, who in turn brought in former Georgia Secretary of State Karen Handel. Handel, who is strongly opposed to abortion, was hired as chief lobbyist and asked to work on the problem of the protestors. Along with Hammarley, she came up with several options that included everything from doing nothing to defunding Planned Parenthood in perpetuity. Hammarley warned Komen that doing the latter would cause severe problems, so the board elected to cancel funding for one year and then reevaluate.

Komen notified Planned Parenthood, who issued a press release decrying the decision. Immediately, social media exploded with anti-Komen messages—1.3 million on Twitter alone—that ranged from irreverent to near homicidal. Komen seemed utterly gobsmacked by the response. A campaign called “Komen Kan Kiss My Mammogram” sprang up, designed to raise $1 million for Planned Parenthood to replace (and then some) what Komen had withdrawn. Someone hacked a Komen online ad and changed a fund-raising request to say “Help us run over poor women on our way to the bank.” What may have been worse were all the blog posts and mainstream media reports that exhumed negative stories about Komen’s business practices—how much it spent to aggressively protect its For the Cure trademark, how much of its money actually went to research, whether the organization was supporting the right kind of scientific research, whether its pink nail polish might contain carcinogens, and so on.

There was something very retro about Komen’s response—as if they didn’t know how to fight like modern women.

There was something very retro about Komen’s response—as if they didn’t know how to fight like modern women. First, they hid, shutting down all interview requests. Then they tried to cover their tracks, issuing a press release that claimed their decision regarding Planned Parenthood was part of their new “more stringent eligibility and performance criteria” that eliminated any group that was the focus of a congressional investigation. (At the time, Planned Parenthood was the only Komen beneficiary to have such a problem; it had been the focus of a trumped-up investigation, spearheaded by anti-abortion forces, that had come to nothing.) On February 2, a glamorous if somewhat stressed-out Brinker appeared in a video posted on YouTube. Even though stories of internal discord and resignations were already leaking to the press, she reiterated that her decision to end the funding for breast cancer screenings for Planned Parenthood was not political but simply a way of maintaining their standards. “We will never bow to political pressure,” she insisted. “We will never turn our backs on the women who need us the most.”

In this particular fight, however, another Texas woman, Cecile Richards, would get the upper hand. As the head of an organization under constant attack, Richards was adept at keeping her emotions in check. At every press conference, she was the picture of empathy and calm. “Until really recently, the Komen Foundation had been praising our breast health programs as essential,” Richards told the New York Times. “This abrupt about-face was very surprising. I think that the Komen Foundation has been bullied by right-wing groups.” Meanwhile, Planned Parenthood was churning out fund-raising emails, eventually raising $3 million, far more than it usually got from Komen.

Just four days after it all began, Komen reversed itself, and Brinker, looking even more drawn, appeared before the cameras again, this time to apologize and say that the funding to Planned Parenthood would be reinstated. Handel subsequently resigned, berating Planned Parenthood for its “betrayal” in making public Komen’s decision to remove their funding. Both organizations now say they are very happy to be working together again.

Other battles have not turned out the same way. In February the Texas Health and Human Services commissioner—who works at the behest of the governor—signed a rule banning from the Women’s Health Program any organizations that provided abortions themselves or through affiliates. Perry declared that if the federal government didn’t like it, he would find the spare $30 million for poor women elsewhere, regardless of the state’s budget shortfall. In March Kathleen Sebelius, U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services, stood among Houston’s poor at Ben Taub General Hospital and announced that unless Texas relented, the WHP would not be renewed. Federal law required that women have the right to choose their own providers.

The Perry administration was still determined to stop women from being treated by abortion providers, however, so the Health and Human Services Commission distributed a flyer to clients in the WHP, saying they might have to find new places to go—even though there was an injunction in place at the time allowing Planned Parenthood to continue as a provider while the organization’s case against the state made its way through the courts.

In May district judge Lee Yeakel blocked Texas from keeping Planned Parenthood out of any women’s health program receiving federal funds. “The record demonstrates that plaintiffs currently provide a critical component of Texas’s family planning services to low-income women,” he noted in his 25-page opinion. “The court is unconvinced that Texas will be able to find substitute providers for these women in the immediate future, despite its stated intention to do so.” The state is currently appealing.

In June I went to a Planned Parenthood clinic in the Gulfton section of southwest Houston. Like most of the organization’s ten local affiliates, the Gulfton Planned Parenthood is a modest place. It sits in a strip shopping center near a 99-cent store, a pawn shop, and an appropriately bicultural restaurant offering “Sushi Latino.” Which is to say, it’s about as far removed from the clubby halls of the Legislature or the plush headquarters of the Komen Foundation as possible.

For more than a year, Planned Parenthood, and women’s health generally, had been the subject of withering attacks and intense controversies, but the scene inside the clinic was mundane. A television on a wall of the sun-streaked waiting room played some kind of Judge Judy variation. By eleven in the morning, the place was filled with people of all backgrounds—African, Guatemalan, Vietnamese, browns, blacks, and whites—as well as both sexes and multiple generations, not only mothers and their teenage daughters with toddlers, but mothers and their teenage sons. Almost everyone was wearing T-shirts and jeans and staring at their smart phones.

With its encouraging posters depicting happy couples and happy families, the clinic is supposed to be a cheerful place, but the atmosphere was like any doctor’s office where bad news might have to be delivered about an HIV test, breast exam, or pregnancy test. And lately, the information that clinic director Maria Naranjo has to share with her patients includes the fact that, because of the drastic cuts to the family planning budget, the clinic has had to raise its fees. The tab for a wellness checkup, formerly covered by state and federal funds, now costs $133—a prohibitive amount for someone having to choose between paying that or an electric bill. She explained to me that most people think the family planning funds have just run out until the next fiscal year, something they are accustomed to. Most do not understand they are gone for the foreseeable future.

Naranjo, who has worked for Planned Parenthood and other family planning agencies for 27 years, is a bustling, efficient woman with soulful eyes and a lined face. She is the child of migrant workers and was a mother at seventeen. “This is where I can do the best service,” she told me. “I know where they are coming from, and I know how difficult it is.”

Naranjo has established, on her own, a pay-as-you-go program to keep the clients from staying away entirely. But some do anyway. Those are the ones who keep her up at night—the young immigrant who wanted to get birth control for the first time after having her third child, and another, not yet thirty, who couldn’t afford to see a doctor about the growing cancer in her breast. “She doesn’t have anyone,” Naranjo said of the woman, who is also an immigrant. (Every patient has to present proof of legal status.) Naranjo found a private organization willing to provide treatment, but she doesn’t know for how long—or how many more she can continue to impose on their goodwill.

And, of course, there are all the teenagers who no longer have access to free birth control: they now have to come up with $94 for an initial visit and a month’s supply of pills. “That’s where we are seeing a higher incidence of pregnancy,” Naranjo said. She tries to work her sliding scale. She offers condoms, which are cheaper than pills, and then, she said, “you cross your fingers that their partners use them. You know they are going to be sexually active, no matter what you say.”

The cycle Naranjo predicts is this: the state government prevents poor women from getting affordable health care and birth control, so there will be more abortions, more Medicaid births, more expensive complications, and more illnesses caught too late. This doesn’t seem like a good outcome for anyone, much less fiscal conservatives or those who oppose abortion.

“We are going backward instead of forward,” Naranjo said with a pained shrug. And then, like generations of Texas women before her, she got back to work.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Planned Parenthood

- Longreads

- Abortion