One of the best ways to get to know the area is to cruise west along I-10 from Balmorhea to Fort Hancock, passing, in order, the Davis, Apache, Wylie, Carrizo, Beach, Quitman, Malone, and those Finlay Mountains, as well as the Sierra Blanca and Devil’s Ridge. At first sight most of these ranges, not high enough for the kind of bio-diversity you find up in the Guadalupes or Chisos, appear to be nothing more than sweltering piles of collapsing rock. But if you watch for a while, the patterns of stone and sky start to add up to a stark grandeur, and my hope is that you’ll begin to treasure the gaunt beauty of these parts. Then maybe you’ll find yourself jamming on two pairs of socks and hiking boots, ready to roam the canyons and trails high above the desert.

Guadalupe Mountains

Location: Northwestern Culberson County, 110 miles east of El Paso on U.S. 62/180

Highest points:

Guadalupe Peak (8,749 feet)

Bush Mountain (8,615 feet)

Shumard Peak (8,599 feet)

Bartlett Peak (8,497 feet)

Hunter Peak (8,258 feet)

El Capitan (8,064 feet)

Lost Peak (7,818 feet)

The camel may be the ship of the desert, but the Guadalupe Mountains loom like an ocean liner over the callous ranchland of Reeves and Culberson counties. Magnify this metaphor vertiginously when you stand three thousand feet above the desert floor on top of Guadalupe Peak watching as the storms blow in. That’s the hike that everybody wants to take, but there are in fact seventy more miles of trails traversing the 86,000 acres of the Guadalupe Mountains National Park (nps.gov/gumo; 915-828-3251). So while a trip to the top of the state is mandatory, it’s just scratching the surface of what you can find in the only legally designated wilderness in West Texas.

If this is your first time, stop at the Pine Springs Visitor Center to get your bearings. Once you’ve checked in, wander down the short Pinery Trail; the signs that identify various shrubs and trees along the way will bring you up to speed with desert flora. As to fauna, there’s great bird-watching right at the campsite parking lot where the trail to the Peak begins. If you want to explore deeper, this is also the southern end of the transmountain Tejas Trail, which starts with a grueling ascent to the Bowl, a forested lost world hidden behind the high pine tree—dotted ridges of Hunter Peak. You can hike this trail all the way to the campsite at Dog Canyon close to the New Mexico border, but I like to drive here and make this my base, rather than Pine Springs. The fall colors in this remote valley are just as beautiful as the more popular McKittrick Canyon. Those Carlsbad Caverns (nps.gov/cave, 575-785-2232) are a must-see, and you should also try to visit Sitting Bull Falls, the only place for many miles around where your body can be immersed in water. From Dog Canyon, try the Bush Mountain Trail, an exercise in stamina and solitude that follows the western edge of the range, where backcountry campers will enjoy exceptional views of the sunset, or hike up to McKittrick Ridge for the view into McKittrick Canyon. This vista is at its best in October, when the maples put on their colorful display, but the only season to avoid is spring, when winds of more than one hundred miles an hour are common. In summer the high country stays cool, and in winter frequent snowfalls turn the pine forests into a real-life Narnia. If you own a horse, you can take advantage of the corrals at Dog Canyon and Frijole Ranch—sixty percent of the trails are open to riders. Backpackers don’t have to stay on the trails, but there’s no rock climbing or mountain biking allowed. Whatever you do there, what you’ll find in the Guadalupe Mountains is seclusion surrounded by nature in all its glory, from tiny hummingbirds to the grandest peaks. Despite the ravages wrought by accidental fires and the ongoing drought, these mountains are a unique paradise. Stay a week or more and let the world wash off you.

Hueco Tanks

Location: El Paso County, 32 miles northeast of El Paso, 4 miles north of Texas Highway 62 on Ranch Road 2775

Highest point (in the Hueco Mountains): Cerro Alto (6,787 feet)

Out on Texas Highway 62 El Paso never really ends. Sprawling junkyards give way to sun-bleached signs promising heaven in subdivisions that are nothing but geometric patterns carved on the featureless desert sand. The Hueco Tanks, entirely different from the dusty mountains that surround them, lie next to one of these sparsely developed grids as though some lazy Hercules had swept the plateau’s debris into three untidy piles. Years of erosion have sculpted these volcanic rocks into an unlikely oasis of shallow pools and shade; plants, animals, and humans have always been attracted to the food and shelter they provide.

From the early Jornada Mogollon people to the Tigua and Kiowa Indians—who fought each other and the Mexican Army among the boulders—the tribes that lived here left not only pottery and rock paintings that archeologists prize as an irreplaceable record of their cultures but also a spiritual imprint that the Tigua still cherish and defend. More recent visitors—travelers, picnickers, and rock climbers—have left their mark as well, and often in a way that showed little respect for the area’s artifacts or its aura. As a result, Texas Parks and Wildlife, which took custody of Hueco Tanks in 1969, has placed most of these hills off bounds to unsupervised visitors. The climbing community, for whom the Tanks are a world-class attraction, have loudly protested these restrictions. But since this is a State Historical Park (tpwd.state.tx.us/spdest/findadest/parks/hueco_tanks, 915-857-1135), the TPWD is obligated to find ways to protect the cultural and natural resources of the Tanks, and everybody who comes here is required to watch a ten-minute orientation video that underscores the importance of this mission.

A tour of the petroglyphs will convince you that they are worth preserving. Among the nearly three thousand pictographs, there are more than 240 masks from the Jogollon period, the largest collection from this era in the country. Later artists depicted sheep and deer, and then horses, people, and churches, documenting the shift from cave dwelling to an agrarian culture. “Water is life,” the saying goes, and as the once-lush grasslands gradually turned to desert, it’s easy to see how Hueco Tanks came to be considered a sacred refuge.

The climbers have a point, though. Like a puppy must be petted, the Tanks cry out to be explored. There are small and large surprises: caverns and crevices and green valleys, where you might see a bobcat, as I did on a recent misty morning. Mountain lions have been spotted here; gray foxes, prairie falcons, and golden eagles are common, as are snakes, who love the shady cracks in the rocks. The North Mountain is the only self-guided area. There is a limit of seventy people at any time, so a reservation is recommended. To experience the best of the park, take one of the official tours: choose from hiking, bouldering, birding, or a tour of the pictographs. There are campsites and RV hookups in the park, but I think it’s more fun to hang with the climbers at the Hueco Rock Ranch (huecorockranch.com, 915-855-0142), where it’s only $5 a night for a tent site. If you’re serious about climbing at the Tanks, the folks at the ranch have lots of information on park access and run commercial tours to the off-limits areas.

Franklin Mountains

Location: El Paso

Highest points:

North Franklin Mountain (7,192 feet)

Anthony’s Nose (6,827 feet)

South Franklin Mountain (6,791 feet)

Indian Peak (6,512 feet)

Mount Franklin (6, 135 feet)

The Franklins bask in the desert sun like a big lizard with its nose in downtown El Paso and its tail stretching into New Mexico. From this creature’s high sharp spine the bustle of the transborder metroplex seems a long way away, but most of the range is within city limits, so it seems right to start at the nostrils, so to speak, in the city streets, and work up to the spine. At 37 square miles, it’s still the largest urban park in the United States. This is the route I recommend: from Mesa take E. Robinson northeast and keep going as the road makes a sharp right turn at the foothills and becomes Mina Perdida and then Scenic Drive. At the southernmost tip of Scenic Drive—four thousand feet above sea level—pull into the viewing area and study the twin cities through one of three funny-face telescopes.

When you leave the viewing area follow Scenic Drive as it turns north along the eastern edge of the range. Turn left at Alabama and left again onto McKinley Avenue, which zigzags up the mountainside to the Wyler Tramway. Ride the tram to Ranger Peak, which is 5,632 feet above sea level. From here you can see all of El Paso and Juárez, and depending on the visibility, many square miles of Texas, New Mexico, and Mexico.

When you’re ready, drive back down to Alabama and continue north for less than a mile. Turn left into McKelligon Canyon, at the end of which are the State Park Headquarters (tpwd.state.tx.us/spdest/findadest/parks/franklin/, 915-566-6441). If you plan to camp, this is where you get your permit. Rock jocks will want to stay and explore the canyon, with its three established climbing areas: Flower Power Ledge, Picnic Rock, and Peacepipe Arroyo. The adventuresome can attempt the trail from here to Transmountain Drive over South Franklin Peak—it’s really tough, though, and you’ll probably want to have a friend meet you at the other end rather than have to make your way back to McKelligon Canyon. Tent and RV sites—and easier hiking—are on the other side of the mountain, in the newer Tom Mays Unit. At this location hikers can choose from several shorter trails, including the steep climb up to the Aztec Caves, or make the more difficult nine-mile trek to North Franklin Peak. Bring your bike and ride the Sunset Trail—fifteen miles of treacherous cactus-strewn single track with a tough hill at the finish. Be careful not to do what I did, which was to fly over my handlebars onto a rattlesnake laying in a prickly pear.

Davis Mountains

Location: Fort Davis, Jeff Davis County.

Highest points:

Baldy Peak (8,323 feet)

Mount Livermore (8,378 feet)

Brooks Mountain (7,759 feet)

Paradise Mountain (7,723 feet)

Pine Peak (7,680 feet)

Sawtooth Mountain (7,654 feet)

Richman Mountain (7,595 feet)

Whitetail Mountain (7,484 feet)

Sheep Pasture Mountain (6,929 feet)

The Davis Mountains are the angel food cake of the Texas ranges, an airy confection of pinkish rock laced with ribbons of bright green, where cottonwood-lined creeks run through steep canyons. A storm can turn the grassy foothills into Ireland overnight. The area is blessed with our mildest climate—summers barely get into the nineties—and boasts the darkest, starriest skies in the United States, which is why it is home to the University of Texas at Austin’s McDonald Observatory (mcdonaldobservatory.org, 432-426-3640). Fort Davis itself, at the same altitude as Denver, is our only true mountain town, and to my mind, quite the prettiest city in Texas. No doubt it’s the place to be during the dog days of summer.

Fortunately, or unfortunately, depending on your opinion (both points of view flourish in Fort Davis), most of the Davis Mountains are privately owned. Baldy Peak and Mount Livermore, the highest points, are on Nature Conservancy Land. Fort Davis Stables (fortdavisstables.com, 800-770-1911) organizes horseback rides into the Conservancy, with the option of camping overnight, and shorter rides into the historic Sproul Ranch, which runs along Texas Highway 118 from the stables all the way to the observatory. If you want to hike Mount Livermore, you’ll need to wait for one of the Nature Conservancy’s open days or scheduled events. It’s a giddy scramble up steep rocks from the end of the hiking trail to Baldy Peak, but once there, you can see all the way from the Chisos to the Guadalupes.

Chinati Mountains

Location: Near Shafter, forty miles south of Marfa, in Presidio County

Highest Points:

Chinati Peak (7,723 feet)

Sierra Parda (7,185 feet)

Cerro Orona (6,273 feet)

When I saw the map of the long-anticipated Chinati Mountains State Natural Area, I felt as though I had stumbled across the Holy Grail of the Trans-Pecos. It was leaning against a pile of stuff in a back office in Fort Leaton, where a helpful ranger was showing me pictures of the Big Bend Ranch State Park. In 1996 Texas Parks and Wildlife was given 40,000 acres in the Chinatis, but since then there’s been no news about when and if this area might ever be open to the public. Now I was looking at an actual map of the new park, with roads and campsites marked. My ranger friend explained that improving Big Bend Ranch had been first on the to-do list, but now attention is being turned to the Chinatis. Currently, the only part of the range that you can get to is in the swanky Cibolo Creek Ranch (cibolocreekranch.com, 432-229-3737). At this high-end resort, rock stars and industry leaders arrive via private airstrip and are spirited away to the most remote of three guest houses, where a personal chef prepares their meals. Recently, I stayed in a room at the main house, an old Indian fort that has been beautifully restored. Cibolo Creek offers various modes of transportation into the back country—bike, horse, or Humvee. I selected a mountain bike and puffed my way across a couple of miles of grassland into the mountains proper.

Bofecillos Mountains

Location: Southwestern Brewster and southeastern Presidio counties, twenty miles southeast of Presidio

Highest Points:

Oso Mountain (5,072 feet)

Fresno Peak (5,066 feet)

La Mota Mountain (5,016 feet)

Bofecillos Peak (4,974 feet)

Panther Mountain (4,925 feet)

Eagle Mountain (4,819 feet)

Solitario Peak (4,652 feet)

Needle Peak (4,514 feet)

Cerro de las Burras (4,334 feet)

There are no easy trails to obvious peaks in the Bofecillos. The attraction is the rough and rugged landscape, and with it, the opportunity to witness man’s arduous struggle with this harsh environment. The scenery is grand but intimidating—and littered with abandoned stone cabins and rusted machinery, laborious attempts at making a living on the rocky terrain. The 300,000-acre ranch was acquired by Texas in 1988 and is now a state park (tpwd.state.tx.us/spdest/findadest/parks/big_bend_ranch, 432-358-4444). The Sauceda Ranger Station, the park’s headquarters, is still a working cattle operation, and home to the state’s official Longhorn herd. In fact, there’s a biannual Longhorn Cattle Drive, which is headed up by cowboys Ruben Hernandez and Raul Martinez. Hernandez, who was born in a village across the Rio Grande, has camped on the range for months at a time, following the herd from one pasture to another. But scouring the washes and creek beds for scattered cattle, rounding them up, and driving them to Sauceda takes more than a couple of hands, however experienced. Participants will earn their supper and sleep as they learn what it’s like to be a real cowboy. And yes, they get to wear chaps.

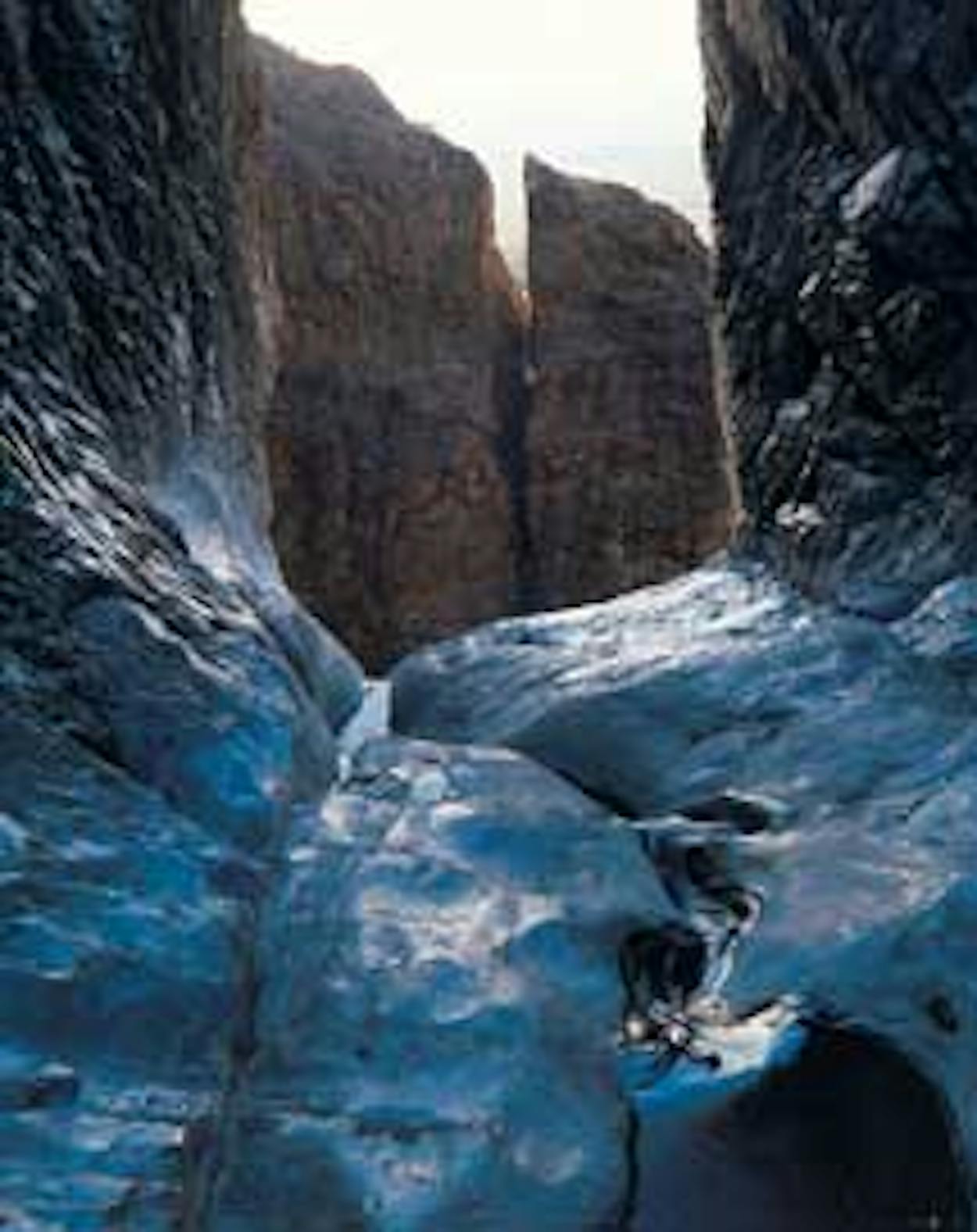

For the first few years of the park’s existence the only access was via sponsored bus tour, but by the time of my first visit in 1997, Texas Parks and Wildlife had added a few campsites. My partner and I spent five cold nights at South Leyva, and during the day, we wandered around the Solitario, trying to make sense of the wrong topo map. To get to legendary beauty spots like Rancherias Canyon and the Madera Falls you had to ride in a Suburban with a ranger or hike for miles across the empty backcountry. But now everything has changed, the result of a ten-year-long improvement program. The combination lock at the Casa Piedra entrance has been replaced with a landscaped portal, and there are more than twenty vehicle-accessible campsites scattered along the new roads that crisscross the park. Keep in mind that these new roads are rough, requiring nerves of steel and tires of high clearance. I stayed at a campsite on the edge of Rancherias Canyon, and even in a Jeep it took an hour and forty minutes of intense concentration to drive the ten miles from the main park road to my destination. At the end of the trail, though, I found a view over the canyon—shared only with a few bees—that I will remember for a long time.

Chisos Mountains

Location: Big Bend National Park, southern Brewster County

Highest points:

Emory Peak (7,795 feet)

Townsend Point (7,599 feet)

Lost Mine Peak (7,421 feet)

Toll Mountain (7,398 feet)

Casa Grande Peak (7,103 feet)

Crown Mountain (6,995 feet)

Ward Mountain (6,890 feet)

Pulliam Peak (6,814 ft)

Vernon Bailey Peak (6,621 feet)

Mount Huffman (6,293 feet)

Sue Peak (5,854 feet)

Carter Peak (5,518 feet)

Rosillos Peak (5,373 feet)

The jagged ring of the Chisos Mountains is probably the state’s best-known natural landmark. And even though Big Bend (nps.gov/bibe, 432-477-2251) is one of the least-visited of our national parks, that still means that every year 350,000 people—most of them Texans—drive out here. I’m sure that nearly everyone makes it up to the Chisos Basin and hikes the paved Window View Trail to watch the sun set between Amon Carter and Vernon Bailey peaks. By the way, cabin 103 at Chisos Mountain Lodge (chisosmountainlodge.com, 877-386-4383) has the only unobstructed view of the Window, but is often booked up to a year in advance.

Popular day hikes like the Lost Mine Trail, the South Rim, and Emory Peak give a sense of the ecological transition from desert to mountain, but the best way to experience this is to hike the Juniper Canyon Trail from the desert floor all the way to the top of the Chisos. Those who want to spend the night in the wild should reserve one of the two campsites along the dirt road to the trailhead. The trail starts with a long slog along Juniper Canyon before ascending steeply to the forested pass north of Townsend Point. As you climb, look out for rare birds, such as the Colima warbler and Mexican jay, and unusual orchids like the saprophytic coralroot or the Hidalgo ladies tresses. By the time you reach Emory Peak, you might well be walking through misty clouds. Enjoy the best view in Texas—you can see over the rim of the range and across the desert for hundreds of miles in every direction.

Although none of the other ranges in Big Bend are quite as noteworthy or as accessible as the Chisos, the park’s hinterlands are an open invitation to more experienced adventurers. You can camp almost anywhere, and though the views may be less dramatic, you won’t have to share them with anybody. (I’m certain that less than ten people climb Rosillos Peak each year.) Try the 11-mile Dodson Trail through the aptly named Sierra Quemada (or Burned Mountains), the southern foothills of the Chisos. This trail joins the Juniper Canyon Trail mentioned above to form part of the Outer Mountain Loop, a 31-mile trek that usually takes three days. The most remote (and maybe the toughest) trails in the park are the Strawhorse and the Telephone Canyon that go deep into the secret peaks of the Sierra Del Carmen and Sierra del Caballo Muerte. This series of mostly parallel ridges runs northwest along the eastern edge of the park and is the northernmost extension of Mexico’s Sierra Madre Occidental. The nearest camp sites are along the Old Ore Road, a four-wheel drive trail that passes points of historical interest like the ore tramway and natural features like Ernst Tinaja, a rock pool that is one of the few reliable water sources for wildlife.

One look around you and it’s obvious that the Trans-Pecos is cut from a different bolt of cloth. It’s hard as nails and gorgeous, and there’s a take-it-or-leave-it attitude. Most folks live here because they love it. The culture is one of fierce independence allied with a strong sense of community. People out here do things for themselves and their neighbors, not for outsiders, but if you want to be part of it, you’ll most likely be made welcome.