On Easter Sunday, David Arnold Jr., a thirty-year-old ranch hand who lives an hour and a half southeast of El Paso in the town of Sierra Blanca, received a call from his cousin in Mexico. Arnold’s cousin lived in Bosque Bonito, a tiny hamlet—just two families and their livestock—about a mile from the Rio Grande. Earlier that day, armed men in a black Suburban had dropped a note in the road, giving the families a week to leave their land. The war raging in Juárez, where rival drug trafficking cartels have been battling one another and Mexican authorities for control of the passage to El Paso, one of the most lucrative drug smuggling routes in the world, had finally reached this bucolic hideaway one hundred miles downstream from the city. There was virtually no police presence in the rural farming towns between Bosque Bonito and Juárez, and in recent weeks cartel thugs fighting for control of the area had developed a kind of scorched-earth policy, aiming to drive every last person out of the small towns and remote ranches that lined the Mexican side of the river. Dozens of people had been murdered, and numerous homes and businesses had been torched. Armed men had even tried to burn down the Catholic church in the nearby town of El Porvenir. Arnold’s cousin decided to take his family and head for the rugged mountains on the south side of the valley to wait out the trouble.

A week later, Arnold got another call: They were running out of food. Bosque Bonito was fifty miles down a dirt road from the nearest town, and there would be no escape from the narcos if they were spotted on that stretch. So Arnold loaded up a box with supplies and headed for the river, through ranchland owned by a friend, to a narrow, steel-cable-and-plank walking bridge once used by Mexican hands when the ranch was still a going concern. The Border Patrol had wanted it torn down for years, but luckily it remained standing. Arnold had been crossing here all his life for family reunions on the Mexican side, and the bridge had once been among his favorite fishing holes.

Now, as he watched the thick brush on the other side for signs of movement, he was worried he was going to die here. Eventually he spotted someone—his cousin, on horseback, looking drawn and exhausted. Arnold would have taken the whole family in if they had wanted to come to Sierra Blanca. But without papers, that would have meant a life in hiding on this side of the border too. “They’re honest people,” he told me. “They don’t want to get into trouble over here.”

Violence in Juárez has been in the news before—the unsolved murders of hundreds of young women began making headlines in 1993—but in recent years the city has descended into an unprecedented level of chaos. The killing began in earnest in 2008, when the world’s largest drug trafficking organization, western Mexico’s Sinaloa cartel, began muscling in on territory long controlled by the local Juárez cartel. The United States is the world’s biggest market for illegal drugs, and the cartels move billions of dollars’ worth of Mexican marijuana and Colombian cocaine through El Paso every year. Authorities in Juárez have been powerless against the warring factions, or worse: After promising to root out public corruption, Mayor José Reyes Ferriz was obliged to replace half of the entire municipal police force, which was largely in league with the Juárez cartel. In March 2008 Mexican president Felipe Calderón sent federal troops to the city, but this only escalated the violence, leading to almost daily shoot-outs that have killed not just cartel henchmen and law enforcement officers but also a growing number of bystanders.

Meanwhile, faced with a loss of drug trafficking revenue due to the mayhem, cartels and their affiliated street gangs have turned to other lines of business, like kidnapping and extortion, making life unbearable for the average city resident. More than 10,000 of the city’s businesses have closed, and most Juarenses don’t go out after dark. And yet as bad as life in Juárez has become, it is just one flash point in the ongoing trouble throughout Mexico. Major cartel battles are under way for control of smuggling routes in and around the Mexican border towns of Nuevo Laredo and Matamoros, and Calderón has also been obliged to send troops to cartel strongholds in southern and western Mexico. Since December 2006, when Calderón first deployed the army, more than 23,000 people have been killed nationwide in cartel-related violence. Political candidates, including the front-runner in the Tamaulipas governor’s race, have been assassinated, drawing comparisons to the situation in Colombia in the eighties and nineties, when drug lords openly battled the government for control of broad swaths of the country. Mexico is undergoing the biggest threat to public order and the rule of law since the Mexican Revolution, in 1910.

Faced with the alarming prospect of a failed state on our southern border, the U.S. has backed Calderón’s efforts with the $1.6 billion Merida Initiative, the lion’s share of which has gone to providing helicopters and other equipment to the Mexican military. On this side of the border, the focus has been on preventing “spillover violence,” a term that seems to have originated in congressional debate and quickly become ubiquitous without ever really being properly defined. In March, Texas senators John Cornyn and Kay Bailey Hutchison sent a letter to President Barack Obama urging action on border security. “The spillover violence in Texas is real and it is escalating,” they warned. In a subsequent conference call with reporters, however, Cornyn was unable to name any actual examples of the phenomenon he was urging the administration to take seriously. “I should have said the threat of potential spillover violence,” he explained.

Yet Cornyn and Hutchison’s letter seemed prescient ten days later, when a rancher named Robert Krentz was shot dead on his property in southern Arizona, apparently by a Mexican drug trafficker using the ranch as a smuggling route. Suddenly border security was at the top of the national agenda, and it seemed every news organization in the country was covering the lawlessness in Mexico. Long-simmering resentment over the federal government’s inability to stem illegal immigration—now cast as a matter of life and death for U.S. border residents—boiled over in Arizona, where the legislature passed the controversial Senate Bill 1070 into law, requiring police to check the immigration status of anyone they suspect of being in the country illegally. In Washington, conservatives announced that any discussion of comprehensive immigration reform—which would provide a path to citizenship for most people now here illegally, something both parties have said is a goal—could not begin until the security issue had been resolved. Obama, feeling pressure from elected officials in both parties, announced on May 25 that he was sending 1,200 National Guard troops to the border. In June, he asked Congress for an emergency appropriation to hire 1,000 new Border Patrol agents.

But was the shooting in Arizona a glimpse of the future or an anomaly? Lost in the debate is the fact that violent crime rates in southwest border communities are among the lowest in the nation. Violent crime actually declined in Arizona in 2009, according to the FBI, even as the situation in northern Mexico deteriorated. Two and a half years into the crisis in Juárez, El Paso remains one of the safest large cities in America. There have, of course, been incidents of violence related to the drug trade; drug trafficking has always been an inherently dangerous business, even before the current trouble in Mexico began. But efforts in some circles to catalog any incident of drug-related violence that occurs in the Southwest as evidence of spillover have been rejected by federal law enforcement officials. At a hearing in Washington, D.C., in May, at the height of the media frenzy about spillover violence, Anthony Placido, the chief of intelligence for the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, told senators that the violence in Mexico had “fostered a level of concern in the U.S. that is in our opinion disproportionate to the extent of violence that’s actually occurred on American soil to date.”

Even if gunfights in the streets don’t materialize, however, the chaos in Mexico is changing life on the Texas border, in ways sometimes counterintuitive and sometimes difficult to see. In places like El Paso, the story of David Arnold Jr.’s extended family is being repeated a hundred times a day all over the city. Elsewhere, some towns are thriving—much as border towns did during the Mexican Revolution, when merchants made a fortune selling supplies and ammunition to both sides—while others, deprived of essential cross-border commerce, are in danger of dying on the vine. And the violence is not the only worry. There is also a palpable ambivalence about the push in Washington for increased border security. Every Texas border town is really just one half of a larger community that straddles the river, joined by culture, blood, and commerce. Even before the violence in Mexico began, tensions over illegal immigration nationwide were already driving a wedge between these communities, symbolized by the controversial border fence. With several Texas lawmakers promising to introduce an Arizona-style bill when the Legislature convenes this winter, there are really two specters haunting our border towns: the mayhem in Mexico and the grim rhetoric it has inspired.

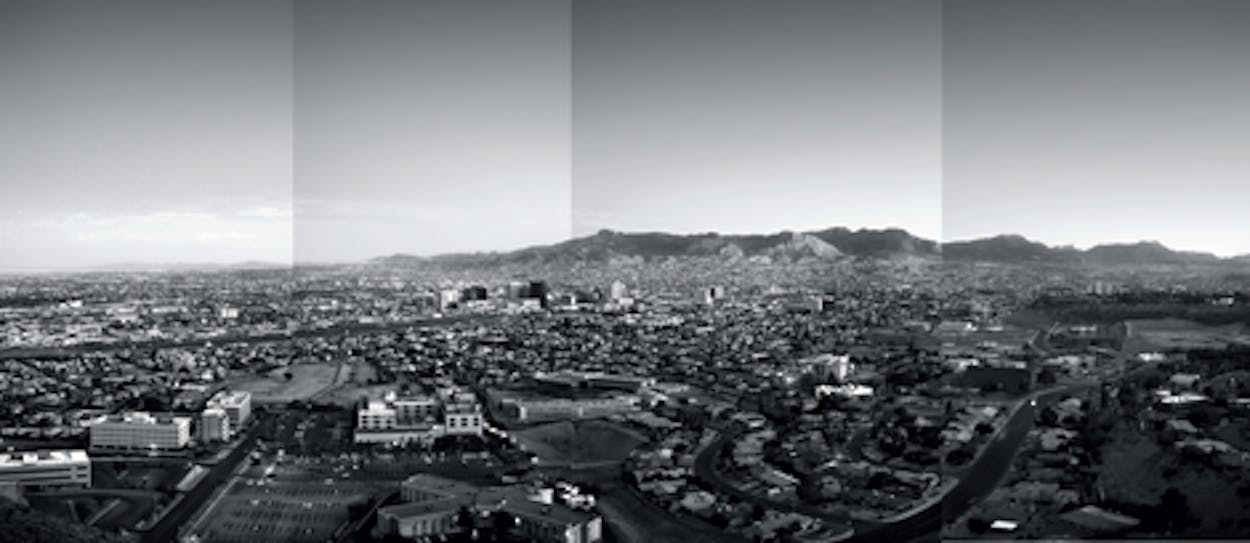

El Paso

It is hard to find a law enforcement official in El Paso who is worried about the trouble in Juárez crossing the river. As of May 26, the day I spoke with Joe Arabit, the special agent in charge of the El Paso division of the DEA, the annual tally of murders in the city of Juárez had reached one thousand. “In El Paso, we’ve had one,” Arabit said, and that killing was not related to drug trafficking. In Juárez, cartel hitmen, or sicarios, as they are called, can kill with impunity. Convictions for any sort of crime are extremely rare in Juárez, as they are in Mexico generally. A recent report from the Mexican attorney general revealed that only 5 percent of murders attributed to organized crime since 2006 have ever been investigated, even though 1,100 of the victims have been cops, soldiers, or government officials. But the traffickers know that targeting anyone in El Paso, much less a law enforcement officer, would prompt a massive reaction from the city’s considerable contingent of local and federal officers. “This is a business for these people,” Arabit said, “and they are not going to do anything to jeopardize their cash flow or disrupt their supply chain.”

Because many of the killings in Juárez are meant to send a message to government officials or rival cartels, the crime scenes can be spectacularly gruesome. The buzz this particular week in May was about the bodies of three headless men that had been found dressed in women’s underwear. The buzz in El Paso, meanwhile, was about the world’s largest women’s bowling tournament, which had filled the city’s hotels with middle-aged women in matching T-shirts and practical shoes. Less than a mile from the most dangerous city in the Western Hemisphere, downtown El Paso felt about as ominous as a busy afternoon at a Sam’s Club in Wichita, Kansas. “Is there a possibility of violence spilling over? I suppose so,” Arabit said. “But we haven’t seen it.”

It takes only a few days in El Paso, however, to realize that this is largely beside the point. Implicit in all the vigilant waiting and watching for “spillover violence” to materialize is the idea that there is a difference between violence that occurs in Mexico and violence that occurs in the U.S., and this is why the term is not considered very useful the closer you get to the border. As far as most El Pasoans are concerned, the violence is already happening to “us,” since “us” in this part of the state has always included loved ones who happen to live on the other side of the river. The worry here is not first and foremost keeping the trouble confined to Mexico; it’s getting people you care about out of Mexico, however you can. That is why, for many El Pasoans, making the border harder to cross is not part of the solution, it is part of the problem.

According to an estimate recently floated by the El Paso chief of police, 30,000 Juarenses have already made the move to El Paso, though nobody really knows for sure if that number is accurate. Officials in Juárez believe the number is much higher, since according to their count there are more than 100,000 empty houses in Juárez. (Many of those, it should be noted, belonged to former maquila workers, some 75,000 of whom have been laid off since the global recession began, in 2008.) The first to cross were U.S. citizens or legal U.S. residents living in Juárez, who had always been able to relocate at will. Then came wealthy Mexicans, those who could obtain an investor visa by putting $100,000 or more into a business venture on the U.S. side. Next were children and spouses of U.S. citizens or legal residents, who can apply for residency through a family reunification program, if they have the money for a lawyer. And then there are those with laser visas, also known as border crossing cards, which permit a thirty-day visit to the U.S. and are generally used for shopping or running errands near the port of entry. The number of people living illegally in El Paso on an overstayed laser visa is probably in the tens of thousands. Immigration officials have begun cracking down on abuse of the visas, but they have always been out of reach for most people in Juárez anyway. U.S. consulate officials will not give them to people they suspect might be coming to the U.S. to work, so if you don’t have a bank account or own a home in Mexico, the chances of getting a laser visa are slim.

“If you have money, you can get out,” said Carlos Spector, an immigration attorney in El Paso. “If you don’t, you’re on your own.” Like all of the immigration attorneys in town, Spector, who has a modest office about a mile from downtown, has been inundated with calls seeking help. “My cousin, my aunt, my grandma—you’ve got to help me get them out of Juárez.” More often than not, Spector tells them there is nothing he can do. In the summer of 2008, he took on the case of Emilio Gutiérrez Soto, a reporter for a Juárez newspaper whose life had been threatened after he reported on a series of crimes allegedly committed by Mexican soldiers. Gutiérrez and his son drove to an international bridge in a nearby town in New Mexico and presented themselves to immigration officials, requesting political asylum in the United States. They were put into a detention facility in El Paso. After two months, his son was allowed to move in with a relative in El Paso, but Gutiérrez was kept in custody while authorities investigated his claims. This was standard operating procedure at the time for anybody expressing fear for his life at a border crossing. Spector, who has a knack for media work, got his client’s story on television in El Paso, and the international group Reporters Without Borders began pressuring the Department of Homeland Security to let him go. After seven months in jail, Gutiérrez was abruptly released.

After the embarrassment of the Gutiérrez case, Homeland Security officials announced that such detentions would no longer be standard policy. Yet officials have remained skeptical about Mexicans seeking asylum. More than 9,000 have applied at border crossings in the past three years, but only 183 have been allowed to stay in the United States. Spector sees a bureaucracy that has not come to terms with the magnitude of the crisis on the other side of the river. “What they need is a team of twenty asylum judges, down at the bridges, ready to take cases as they come in,” he said. “It’s like nobody is in charge.”

Spector and other advocates concede that refugees fleeing the violence in Mexico do not fit neatly into any of the protected categories identified by existing asylum law, which is meant to apply to people who are being persecuted by governments because of their race, religion, nationality, political opinions, or membership in a particular social group. “It’s difficult to protect people caught in the crossfire under asylum law,” said Barbara Hines, an immigration expert at the University of Texas School of Law. If refugees can show that the government in their home country is unwilling or unable to shield them from violence, however, they may have a case. The Obama administration could also grant something called “temporary protected status” to people fleeing the violence in Mexico, as it did for Haitians in the country illegally following the devastating earthquake there, to prevent them from being immediately deported.

Ruben Garcia, who runs a refuge for immigrants called Annunciation House, likens the situation in El Paso and Juárez to the situation at the border in the eighties, when thousands of Central Americans came north, fleeing the civil wars in Guatemala and El Salvador. Their requests for political asylum were routinely rejected, in part because many of them were claiming repression by governments that the Reagan administration was supporting with counterinsurgency aid. “Accepting their claims was bad politics here in the U.S.,” Garcia said. In 1991, however, the federal government settled a lawsuit alleging that the requests had been improperly denied, and thousands of people were allowed to reapply.

“In order to start granting asylum cases now, we would have to admit that Calderón’s plan isn’t working, and nobody in Washington wants to do that,” Garcia said. And then there is the anti-immigrant political climate to consider, with midterm elections coming up. “Creating a form of relief for Mexican nationals to remain in the U.S. on a long-term basis is a nonstarter in Washington,” said El Paso immigration lawyer Kathleen Campbell Walker, a past president of the American Immigration Lawyers Association.

Nevertheless, local officials continue to push for it. At noon on a blisteringly hot day in June, a small group convened a press conference in an empty lot near the Texas side of the Santa Fe Bridge to call for reforming the asylum process. Among them were three El Paso city council members, including Beto O’Rourke, an earnest and affable young man in a dark suit. “We’re here for Juárez, because nothing the federal governments have done on either side of the bridge has decreased the violence,” O’Rourke said.

The group had another demand as well: legalizing marijuana, which accounts for at least half of cartel profits. Legalization, O’Rourke argued, would remove the underground market for the drug, which would mean a “giant step toward resolving the problem in Juárez.” This is not a fringe position in El Paso, where the city council has taken up the legalization issue in the past. O’Rourke and his compatriots were armed with an Associated Press article that had run the week before to mark the fortieth anniversary of the drug war in the U.S.; it was headlined, “U.S. Drug War Has Met None of Its Goals.”

El Paso congressman Silvestre Reyes, a former Border Patrol sector chief, was not in attendance, but he had sent his press secretary, Vincent Perez, to deliver the anti-legalization argument, which he gamely did for the news cameras. As the press conference was winding down, Perez, a soft-spoken man in his late twenties, was accosted by Oscar Martinez, a University of Arizona professor who had helped organize the event. “Why don’t you get on the right side of this?” he asked a wide-eyed Perez as the cameramen suddenly renewed their interest. “Why don’t you listen to what is real?” He waved the AP story in Perez’s face. “Don’t you know what’s going on over there?”

Later, in a phone interview, I asked Congressman Reyes if he thought something like temporary protected status was in order for drug violence refugees in El Paso. “If the situation gets to the point of people being driven out of Juárez, that’s something we would have to consider,” he said. I asked him about the chief of police’s estimate of 30,000 refugees already in the city. Reyes told me he had been unable to substantiate that number, though he would not say whether he thought it was too high or too low. “We have to separate fact from supposition,” he said. As long as the Mexican government was working to solve the problem, he said, we had to let them handle it themselves. When would we know, then, that the situation in Mexico had reached a crisis? “We will know it when it happens,” he said. “If it happens.”

McAllen

A crisis of sorts was unfolding in McAllen on the morning I arrived in early June. The front page of the local paper, the Monitor, announced the bust of Hernan Guerra, the police chief of Sullivan City, a small town twenty miles to the west. Guerra, who was arrested along with more than two dozen other residents of Sullivan City, McAllen, and surrounding towns, was allegedly on the payroll of both the Gulf cartel, based across the river in Reynosa and nearby Matamoros, and the Zetas, a cadre of former Mexican military commandos who once served as muscle for the Gulf cartel but have since entered the smuggling business for themselves. The two rivals have been locked in a bloody battle for the past eighteen months, and the Valley was still digesting news of a shoot-out the night before in Matamoros. A group of heavily armed Zetas had attacked a police station after officers had inadvertently arrested the teenage son of a Zeta member, only to be set upon themselves by Gulf cartel gunmen coming to the aid of the police.

It was all a little hard to imagine, standing in the balmy afternoon sunshine in front of the Sullivan City municipal building, a low white structure with cheap siding and crudely framed windows. A skinny palm tree partially covered a mostly straight hand-lettered sign over the entrance that read “City of Sullivan City.”

Inside, city manager and municipal judge Rolando Gonzalez, a portly man with a friendly, gap-toothed smile, seemed remarkably sanguine, considering that FBI agents had been down the hall ransacking the police chief’s office just 24 hours earlier. The cartels have always had men in Sullivan City, he told me, as they do in all Valley towns, and he listed for me a roll call of prominent law enforcement officials who had been busted over the years, including, most recently, Starr County sheriff Reymundo Guerra. None of it was new, and none of it meant that the Valley was becoming an unsafe place to live. “There’s no goddam spillover violence,” he said.

In fact, an argument could be made that there has never been a better time to live in the Valley. McAllen had been booming for years before the recession hit, and it was the first large metro area in the entire country to bounce back to prerecession employment levels. David Guerra, the president of IBC bank in McAllen, told me over dinner at a local steakhouse that the reason was a tremendous infusion of cash from Mexico. In recent years the city has evolved into the retail hub for a region that extends all the way down to the Mexican industrial metropolis of Monterrey, two and a half hours away by car. Shoppers driving in from Mexico account for a third of the purchases at McAllen’s mall, and McAllen’s new hospitals are also heavily patronized by Mexicans paying cash for services they cannot receive in Reynosa or Matamoros. More recently, Guerra said, Mexican nationals fleeing the violence and turmoil from Matamoros to Monterrey had been buying homes and moving their families into McAllen. Many were starting businesses as well. “I hate to say it,” Guerra said, “but the effect of the trouble in Mexico on McAllen has been more good than bad.”

The same might be said of drug trafficking in general, which has for decades been a reliable provider of capital for the Valley, one that has proved to be remarkably immune to the recession. In 2009, as credit markets froze around the globe, Antonio Maria Costa, head of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, told reporters that cash generated by illegal drug trafficking had become one of the only sources of liquidity in the global economy. In other words, when banks stopped spending money, narcos didn’t: Drug cash laundered into the legitimate economy was building hotels, buying sports teams, paving parking lots, and putting people to work all around the globe. It’s difficult to overstate the importance of drug trafficking to the Mexican economy. In 2009 oil exports—Mexico’s largest official source of revenue—brought in roughly $31 billion; some estimates put the value of the drug trade at twice that amount. Even the most conservative estimate, $19 billion per year, is still equivalent to the total yearly income of all the farms and ranches in Texas.

How much of that money stays in border towns like McAllen and Reynosa is difficult to say. How do you calculate the economic impact of an industry in which nobody admits to participating? It’s safe to assume, however, that the number of people on the payroll of the cartels who are, for example, within a day’s drive of the mall in McAllen runs in the thousands. How much drug money makes it into the banks? Very little on the Texas side, according to David Guerra. “You wouldn’t believe the reporting requirements we have now on cash deposits,” he said. “When somebody from a foreign country wants to do business with me, I ask them, ‘Okay, where did this cash come from?’ We do enhanced due diligence to determine that the source of the funds is legitimate.”

Guerra scoffed at the suggestion that drug money was propping up the economy in McAllen, but if he was offended by my question, he didn’t show it. After dinner he took me downtown to a four-block stretch of South Seventeenth Street, where at least a dozen new bars and restaurants have opened to accommodate both Texans and Mexicans no longer willing to risk partaking in Reynosa’s once popular nightlife. At Le Rouge Luxury Club, a nine-piece Dominican band played Latin dance music to a respectable Thursday-night crowd. Co-owner Joe Olmeda told me that on Friday and Saturday nights, high rollers from Mexico reserved tables for $500 per night. A bouncer ran his metal detector wand over everyone who walked through the door, though Olmeda told me he’d had little trouble. If cartel men were drinking here, they were keeping a low profile.

The next morning, there was more essential reading on the Monitor’s front page. It seemed that a McAllen developer named Marin Herrera had been among those picked up by federal authorities in the same sweep that caught the Sullivan City police chief. He was accused of having laundered millions in drug trafficking proceeds by building and selling homes in his Villa Real Estates development in Mission, on the west side of McAllen. (Herrera, for the record, banked with one of Guerra’s competitors.) As luck would have it, I was already headed toward Mission, where a real estate agent named Sally Cuellar had promised to give me a tour of Sharyland Plantation, a high-end subdivision favored by Mexican nationals immigrating to McAllen.

Cuellar, who wears her hair in a bouncy ponytail and has a disarming giggle, is a top seller at Sharyland Plantation, which is owned by the Hunt family in Dallas and was named for John Shary, a pioneer in the citrus business. With us in Cuellar’s Honda minivan was a sales agent for one of Sharyland’s builders named Nan Coghill, a round-faced South Carolina transplant who moved to McAllen five years ago when her husband was hired as a maquila plant manager in Reynosa. The Mexican national team was playing a World Cup match that morning, and both women wore team jerseys.

With 3,200 houses, Sharyland Plantation is like a town unto itself, six thousand acres of palm-tree-lined avenues and man-made ponds garnished with beautiful bougainvillea bushes. The subdivision has its own elementary and junior high schools, said to be the best in the county. Cuellar wanted me to see Antigua, a gated community inside the subdivision where the most expensive homes were being built, virtually every one owned by a recent transplant from Mexico. We followed a freshly laid road across a treeless plain planted with enormous homes, some in the Mediterranean style, some starkly modern. “Mexicans love the modern look,” Cuellar explained.

About half of the homes in Sharyland Plantation as a whole are owned by Mexican nationals. Some are used as vacation homes, but more and more are occupied year-round. “Since the recession, they’re the only ones buying here,” said Coghill, who is the head of the Maquila Women’s Association but hasn’t sold a house to a maquila manager in quite some time. Some of her clients have literally arrived on the run, with hastily packed bags and harrowing tales. “One couple told me their son had been beheaded,” she said. “It’s just horrible.” Many of them also arrive with huge sums of cash. “They walk into my office with $300,000 in a bag,” Cuellar said. There is no bank involved in many of the sales at Sharyland Plantation, nor is there much of a paper trail concerning the legal status of the buyers or the provenance of the money that changes hands.

As we finished our tour, I pulled out my copy of the Monitor and asked if either of my guides had heard of Marin Herrera, the developer who had been arrested earlier in the week. “Oh, that loser,” Cuellar said, looking at the paper as if it had been on the bottom of a birdcage. Neither woman had heard of Villa Real Estates, which was reported to be on Glasscock Road, not far from Sharyland Plantation, but they were game to search for it. “Let’s go see what they’re going to confiscate,” Cuellar chirped, and Coghill laughed heartily. “Not uncommon around here!” We drove north through older subdivisions until the street signs started to thin and we entered citrus groves. The road seemed to go on endlessly. “I’m telling you, it’s not out here,” Cuellar said. Finally we found the neighborhood in question. We looked around at what Herrera had wrought with what the feds said was dirty money: a square plot of land perhaps twenty acres in size, with half a dozen modest houses surrounded by empty lots arranged along a single U-shaped road. On adjoining lots in the rear of the development, work was under way on a large brick house with brutal angles and small windows. Men in long-sleeved shirts with ball caps shading their darkly tanned faces looked up as we passed. “Somebody better tell them they’re not getting paid,” Coghill quipped.

We slowed to watch them. They were hard at work supposedly making dirty money clean, though they did not know it. As far as they were concerned, it didn’t matter anyway. And on this side of the river, out of sight of the shoot-outs and the kidnappings and the mayhem, it was hard not to wonder why we were supposed to care either. Wasn’t Herrera helping build McAllen, just like the Hunt family? A realtor, a banker, a general contractor, an insurance agent—the list of people who had gotten a piece of even a modest project like this one was impressive. And now the government was going to seize all this land and sell it once again, laundering Herrera’s alleged drug money a second time and eventually returning the proceeds, as the feds do, to the agency that made the bust, so that more agents can be hired. Some of those new agents would likely work right here in the Valley, where the demand for investigators is great. They’d buy houses and go shopping at the mall with their families—another win-win for McAllen.

The next morning I visited with McAllen mayor Richard Cortez in a nicely appointed conference room at the accounting firm where he is a retired senior partner. I asked him if he was worried that any of the newcomers flocking to the safety of McAllen were in the smuggling business themselves. “The great majority of people here are good, honest people,” he said. “Then there is the other kind, and I’m sure we have some of them coming over. So far we have had a peaceful coexistence with them,” he said. More troubling to Cortez was the public policy response to the violence in Mexico, specifically the possibility that the State of Texas or the federal government would take the same tack as Arizona, conflating the problem of illegal immigration with the threat that drug traffickers pose to public safety. “If we have a plan that doesn’t distinguish between the two, then we have a plan that will fail,” he said. The majority of farmworkers in the Valley, Cortez said, were undocumented, and increased security on the border was making it difficult for growers to keep their operations running. As the prospects for comprehensive immigration reform grow dimmer in Washington, Cortez said, some Valley growers are starting to relocate their operations to Mexico. “We’re spending all this money to put people out of work,” he said. “How is that keeping drugs and thugs out of our country?”

Del Rio

Spending time in a town like Del Rio, it’s hard to miss a fact that tends to get lost in the national debate over border security: Even before the current round of violence began in Mexico, the U.S. government had already assembled an army of unprecedented size on our southern border. Following 9/11, the Border Patrol doubled the ranks of its agents, from 10,000 to 20,000 in just five years, in what has been called the largest peacetime recruiting effort in U.S. history. In Del Rio, there are now roughly 1,600 agents in the sector, up from about 900 just three and a half years ago. The majority of them live in Del Rio itself, a steadily growing town of about 40,000, where the green-and-white pickups and SUVs of the agency are ubiquitous. Now that border security has become the watchword in Washington, the future for rural Texas border towns could look a lot like Del Rio: Long celebrated by conservatives for its tough approach to illegal immigration, it has become in essence a kind of Homeland Security company town. For better or worse, Del Rio may be a harbinger for a new kind of border economy, one that revolves around security.

“That federal check coming in every month has sure helped this town,” said Charlie Bruce, who retired in 2000 after twenty years as Del Rio’s chief of police. As we drove past sage-covered hillsides and rugged bluffs on a friend’s ranch near the Rio Grande, Bruce told me that when he was first hired by the police department, in 1957, the Border Patrol was a tiny presence in town, and he knew every agent. “Now they come from all over the country to work here,” he said. “Some of ’em get here and decide spending all day out in this heat chasing Mexicans isn’t for them,” he laughed. Those who stay buy comfortable new homes on the north side of town and take their boats out on nearby Lake Amistad on the weekends. They have essentially added a middle class to this traditionally hardscrabble town, albeit a largely imported one. New agents start at a salary of $42,000; after three years, agents willing to work overtime can earn more than $70,000. (For comparison, a new airman fresh out of high school at nearby Laughlin Air Force Base, which for decades had been the town’s main economic engine, earns less than $18,000.)

As we topped a steep hill, we spotted a Border Patrol truck coming toward us on the narrow gravel road, and Bruce slowed to a stop and rolled down his window. Agents were always cruising the privately owned ranch roads near the river, and Bruce knew a few of them by sight. This one, a young Hispanic man with dark sunglasses, was new to him. The agent started to mutter something officious, but Bruce cut him off with a jolly greeting.

“I didn’t know you guys worked out here in this heat,” he said. “You need to get you a night shift!” The agent laughed, apparently deciding to skip the official script for a backcountry encounter, which inevitably includes some form of the question “What are you doing here?”

“My name is Agent Roldan, and I’ll be in the area for the next couple of hours,” he said instead.

“Where you from, Roldan?” Bruce asked.

“Originally, Puerto Rico,” he said. Under the circumstances, it came out sounding like an admission of some kind, and both men laughed a little nervously.

“If we see anything, we’ll call you,” Bruce said, and we drove off.

Like McAllen, Del Rio has weathered the recession better than most towns its size, but the savior here has not been Mexico—it has been Washington, D.C. The annual payroll for Del Rio sector agents is roughly $100 million, and that does not include support personnel or the hundreds of officers employed by other immigration agencies under the aegis of the Department of Homeland Security, such as Customs and Border Protection, which checks vehicles and people crossing at the ports of entry, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement, which conducts investigations farther from the border. “Homeland Security is the only thing keeping us afloat,” said Blanca Larson, the president of the chamber of commerce and the manager of Del Rio’s Plaza del Sol mall. Trouble across the river in Ciudad Acuña, while not nearly as bad as in Juárez or even in Reynosa, has hurt the tourist industry on both sides of the river, which in turn has put a dent in the number of Mexicans coming across to spend money at the mall. Layoffs in the maquila industry have added to the downturn.

Border security, however, has proved to be a recession-proof industry, as has an ancillary industry that has sprung up in Del Rio: the for-profit detention of illegal immigrants caught at the border. Under a program called Operation Streamline, pioneered here five years ago, illegal immigrants are no longer immediately deported. Instead they are held in the Val Verde Correctional Facility, a 1,344-bed jail owned and operated by a publicly traded company called the Geo Group, and charged with a misdemeanor in federal court, punishable by up to 180 days in prison. Only after serving their sentences are they deported; if they are caught crossing again, they can be charged with a felony. The expense to the federal government is considerable, but the violence in Mexico has renewed calls for expanding the program to the entire border.

One morning I sat on a bench behind the witness stand in U.S. Magistrate Collis White’s courtroom, the only seat I could find in a room packed with undocumented immigrants captured crossing the river in the previous week. They sat hip to hip, with handcuffs on their wrists attached by a chain to shackles around their ankles and earphone cords dangling under their chins so that they could hear the translator standing next to the judge’s dais. They wore the same jeans and T-shirts and cheap tennis shoes they had been wearing when they were caught, in most cases after lengthy walks through the desert, and the courtroom had the salty smell of sweat. Fifty men, along with a handful of women, were being tried at the same time, all represented by the same court-appointed attorney. Each person stood in turn when his name was called and glumly listened to the charge against him and then to the brief defense offered by his attorney, a hefty man with a voice like a children’s librarian, who read from notes without looking up from his binder. “Your honor, the defendant is from Chiapas, Mexico. He is a bricklayer by trade. He went to school to the third grade. He is married, with four children, and he came to the U.S. for economic reasons.” Everyone pleaded guilty, and then Judge White pronounced sentence, in most cases ten days in jail, unless the defendant had previously been caught and convicted.

As the hours went by, the proceedings took on the feel of factory work. Two federal marshals circled the room, making sure nobody fell asleep or removed his earpiece. Only the defense attorney’s lines changed, and even then the story was always a variation on the same theme: “elderly mother,” “two sets of twins,” “daughter’s eye operation,” “no work.” One grim-faced twenty-year-old from El Salvador had been deported the previous winter and had made the long, expensive, and dangerous trek back across the entire length of Mexico. Now he would be sent all the way to Central America again, after he served the ninety days Judge White gave him.

Operation Streamline, which has also been implemented to varying degrees in Laredo and in parts of the Valley, has turned illegal immigrants into a kind of commodity for the border communities in which they are caught. Fees for the court-appointed attorneys who work at the mass trials in Del Rio, held five days a week at the federal courthouse, are calculated using wholesale discounts: $100 a head for 1 to 14 clients, $75 a head for 15 to 49, and $50 a head for dockets over 50. The federal government pays Val Verde County about $50 per day to house each immigrant awaiting trial, and the county contracts with Geo to do the actual work. With the jail averaging 90 percent capacity, the county is earning at least $60,000 per day, less what it pays Geo. Known for its low wages, the company, which employs three hundred people at the detention center, occupies the bottom rung of the security economy in Del Rio, where it has become a sort of employer of last resort for locals who cannot make the grade as federal agents. If the immigrants ever stopped coming, the dent in the economy in this town would be considerable.

Expanding Streamline would require the federal government to double down on the enormous investment it has already made in border security. It would also accelerate the already unprecedented transfer of wealth from U.S. taxpayers to one of the poorest parts of the country; in that respect it may be the only stimulus program amid the current call for fiscal austerity that conservatives in Congress can get behind. But would it work? Apprehensions of illegal immigrants in Del Rio, considered a generally reliable indicator of the volume of people trying to cross, have decreased dramatically, which is why border security hawks often point to the sector as an example of what can be done with the proper will and resources. But how much of the decline in crossings here is due to Streamline is unclear, since apprehensions along the entire border have plummeted in recent years, from 1.2 million in 2005 to 556,000 in 2009. Most analysts believe the decline has been caused by the recession more than any other factor—fewer jobs mean fewer people coming north.

And then there is the more fundamental question about Streamline, the same one raised by SB 1070 in Arizona: Does cracking down on illegal immigration make us safe from the violence in Mexico? When I asked Blanca Larson, the mall manager and chamber of commerce president, for her opinion on Streamline, she gave me a blank look. I reminded her what it was and that it was said to have drastically lowered illegal immigration here. She shook her head. “I don’t think we really noticed the difference,” she said. “People are coming across to look for jobs. They’re not criminals.”

At the border patrol sector headquarters, Deputy Chief Patrol Agent Dean Sinclair told me that he didn’t really need any more Border Patrol agents, though he knew that Obama’s emergency appropriation meant another round of hiring was coming soon. What Del Rio really needed were more inspectors at the port of entry, where a new emphasis on searching Mexico-bound vehicles for drug cash and guns bought in the U.S. on behalf of the cartels was causing long delays up and down the border. The ports of entry are where the action is for northbound contraband too, since cars and trucks have always been the preferred method for moving drugs into the U.S. But border security advocates want to see more agents in the field, in the desert scrub in places like Val Verde County and southern Arizona, where the border seems most porous and the threat of gun-toting traffickers most real.

After an hour touring the bustling headquarters, it was hard not to conclude that the army of agents here is ready for anything. Near the end of my tour, Agent David Toothman took me into a locked closet filled with automatic weapons and high-capacity shotguns with short, menacing barrels. “They know they can’t win if they start a war with us,” he said of the traffickers. But he didn’t expect to see one. The guns that narcos sometimes brought across the river in the backcountry were to protect drug loads from bandits and rival cartel men, he said. “They’re not for us.”

Still, with so many guns on both sides of the border, trouble is never far away. On June 7, a Border Patrol agent in El Paso shot and killed a fifteen-year-old Mexican boy after the agent reportedly came under attack from rock throwers on the Mexican side. Three weeks later, at least seven stray bullets from a shoot-out in Juárez hit the city council building in downtown El Paso. This last incident prompted Texas attorney general Greg Abbott to send a heated letter to President Obama warning that Texas “is under constant assault from illegal activity threatening a porous border.”

You don’t have to be a cynic to infer that inaction by the federal government on border security has clearly become a Republican talking point in advance of the midterm elections and the coming debate over immigration reform. It is hard to imagine what Obama or anyone else can do about stray bullets in the air over El Paso or how more boots on the ground will help someone, such as David Arnold Jr., with family members on the other side of the river, where the violence is all too real. After Mexican federal police and army units began extending their patrols into the tiny towns southeast of Juárez, Arnold’s cousin took his family back to their home in Bosque Bonito. The patrols didn’t last, however, and the family was forced to flee again, this time to a secluded village near the river, far enough away from the road to avoid detection. I asked Arnold what his cousin’s plan was, but there was no plan, he said. “They’re just going to wait and see what happens.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Mexico

- Juárez

- Crime

- Border Patrol