At about noon on June 13, the feast day of Saint Anthony, four actors carried an eight-foot statue of San Antonio’s namesake and brought it to rest in front of the Alamo. They were under the direction of Rolando Briseño, a 58-year-old artist and impresario with closely cropped dark hair and inquisitive, darting eyes. Briseño’s forehead was beaded with sweat, and he wore a crisp, short-sleeved guayabera and a triumphant smile as he led a procession of more than two hundred revelers in the staging of a fiesta designed to, in his words, “reconceptualize the Alamo as a space for celebrating the confluences of cultures—Native American, African, Mexican, and Anglo—rather than a shrine to Anglo dominance.”

On Briseño’s mark, the bearers flipped the statue upside down. “In Catholic tradition, people pray to saints for help,” he said earnestly. “The statue of Saint Anthony is turned upside down when praying for favors. Many of us have asked for years that Mexican Americans, heirs of the builders and descendants of the original people of this city, share in the Alamo legacy.”

Soon the fiesta began. A Native American shaman blessed Briseño and the crowd of mostly Mexican American scholars, artists, and writers and waved a seashell filled with incense as halos of sweet-smelling sage floated through the air. Finally Briseño declared the event a success. For a day at least, Hispanics had participated in the story of the Alamo. With another swift flip, Saint Anthony stood right side up against the backdrop of the mute and immobile facade of the mission. Everyone cheered, including the usual herd of tourists who had gathered in the plaza.

Less than a week later, when the news broke that the state’s attorney general had launched an investigation into the Daughters of the Republic of Texas for failing to fix the cracked and leaky roof in the nearly three-hundred-year-old chapel, some in San Antonio speculated that the public spell cast by Briseño may have supernaturally contributed to the DRT’s troubles. In addition to finding themselves under official scrutiny by Greg Abbott, the powerful matriarchs, who have been the custodians of the Alamo since 1905, are also at loggerheads with Governor Rick Perry for attempting to acquire a federal trademark on the words “The Alamo.”

But that is only one front in the battle for control of what most people revere as the shrine of Texas liberty. As the stewardship of the starchy old guard of the DRT is being threatened, many aspects of the myth of the Alamo are crumbling under the weight of rapid cultural change. And just as in the original battle, no one is backing down. The DRT won’t give an inch. Modern-day secessionists routinely hold rallies in front of the Alamo. Petitions are circulated in support of Arizona’s anti-immigration laws. And activists such as Briseño and Rosie Castro, the mother of San Antonio mayor Julián Castro, have fired back. Complaining of the mythologizing of Anglo heroes at the battle of 1836 and the disparaging of Mexicans, Rosie was quoted last May in the New York Times Magazine as saying this of the Alamo: “I can truly say that I hate that place and everything it stands for.”

The tension has been building for generations. Fifty years ago this month, on October 24, 1960, John Wayne’s The Alamo premiered at San Antonio’s Woodlawn Theatre. As Davy Crockett, Wayne personified the rugged ideal of Texans as an independent breed. Wayne swaggers and says in the film, “ ‘Republic.’ I like the sound of the word. Means people can live free, talk free, go or come, buy or sell. Some words give you a feeling. ‘Republic’ is one of those words that makes me tight in the throat.” For many, Wayne’s speech describes not only the dream of the Alamo but the dream of Texas itself.

“I was in elementary school when the movie premiered,” said Virginia Van Cleave, the chairwoman of the Alamo Committee of the DRT. “It was a huge event for the city. John Wayne came, and the celebration lasted for days.” This year, to commemorate the anniversary, the cash-strapped Daughters have planned a fund-raising gala on the stone plaza in front of the Alamo. Wayne’s daughter and granddaughter will be on hand to accept the Daughters’ first Spirit of the Alamo award, which will be posthumously given to the actor. Once again, the legend of Crockett, dying as Wayne did in the movie, surrounded by an army of Mexicans led by a tyrant, will be celebrated.

On a recent morning Van Cleave was working in the DRT’s inner sanctum, which is located behind the gardens of the Alamo. Her desk was stacked high with papers, architectural drawings, and photos of cracks in the roof of what the DRT calls “the shrine.” Van Cleave is a large, softly shaped woman with a sweet, distinctly Southern disposition. She wore a gold necklace strung with charms of San Antonio’s five Spanish missions. As she leaned forward, the Alamo charm dangled directly over her heart. Since the Alamo has lost two directors and a marketing director—all professionals with deep résumés—in less than two years, Van Cleave, a volunteer, now runs the day-to-day operations. “The DRT is doing its work,” said Van Cleave wearily. “We are under scrutiny, but we believe our good work at maintaining the Alamo for one hundred and five years at no cost to the state speaks for itself. We will protect the Alamo.”

The current battle with the state began with infighting at the organization, whose 6,700 members all meet this requirement: They are lineal descendants of a man or a woman who served the Republic of Texas prior to annexation, in 1846. Feuds among the Daughters are legendary. In 1908, three years after the DRT took control of the Alamo, Adina de Zavala, a zealous San Antonio Daughter, barricaded herself in the convento for three days and three nights to keep another faction of the DRT from tearing it down.

Today’s dispute centers on money. In 2006, faced with a costly list of preservation repairs, the DRT launched an unprecedented $60 million fund-raising campaign. Erin Bowman, a tall, attractive sixty-year-old blonde with a track record of raising significant money for other causes in San Antonio, was named chairman. Though Bowman was herself a Daughter, she did not play by the DRT’s rules. Traditionally most of the DRT’s money has been raised through the sale of tourist trinkets in the Alamo gift shop and through the sale of “Native Texan” license plates. Bowman had other ideas. She chose to meet with potential donors on her own but refused to share her list of contacts with the group.

Madge Roberts, the DRT’s president general at the time, and the other 23 members of the governing committee were infuriated. A wise move might have been to retreat and let Bowman, who had quickly raised $1 million, continue to collect the cash. But as everyone knows, retreat at the Alamo is not an option. In May 2008 Bowman was fired. Undeterred, she and Dianne MacDiarmid, another well-connected Daughter, started the Alamo Endowment to raise money for preservation. Seven months later, the two women were summoned to a hearing at the exclusive Barton Creek Resort and Spa, in Austin. Both were expelled. “It didn’t bother me,” said Bowman, who continues to raise money for the Alamo through her organization. “The women in charge don’t know anything at all about business. They are living in the dark ages. My blood makes me a Daughter, not them.”

Troubles deepened last September when the San Antonio Express-News reported that of the $213,452.30 the DRT had spent from the sale of “Native Texan” license plates from 2005 through 2008, only a little more than $37,000—or 17 percent—had gone to support the Alamo. State officials, from the governor on down, immediately sounded the alarm. (The Express-News, for which I write a weekly column, has published editorials calling for the removal of the DRT; it has responded by calling the coverage “rabid.”) State senator Leticia Van de Putte, whose district includes the Alamo, was particularly miffed when she learned that the DRT had spent $50,000 of the money on the French Legation Museum, an 1841 house it maintains in Austin. “That was a defining moment for me,” said Van de Putte. “I don’t understand how the Daughters justify spending so little for the Alamo, which attracts two and a half million visitors a year and is in desperate need of repair.”

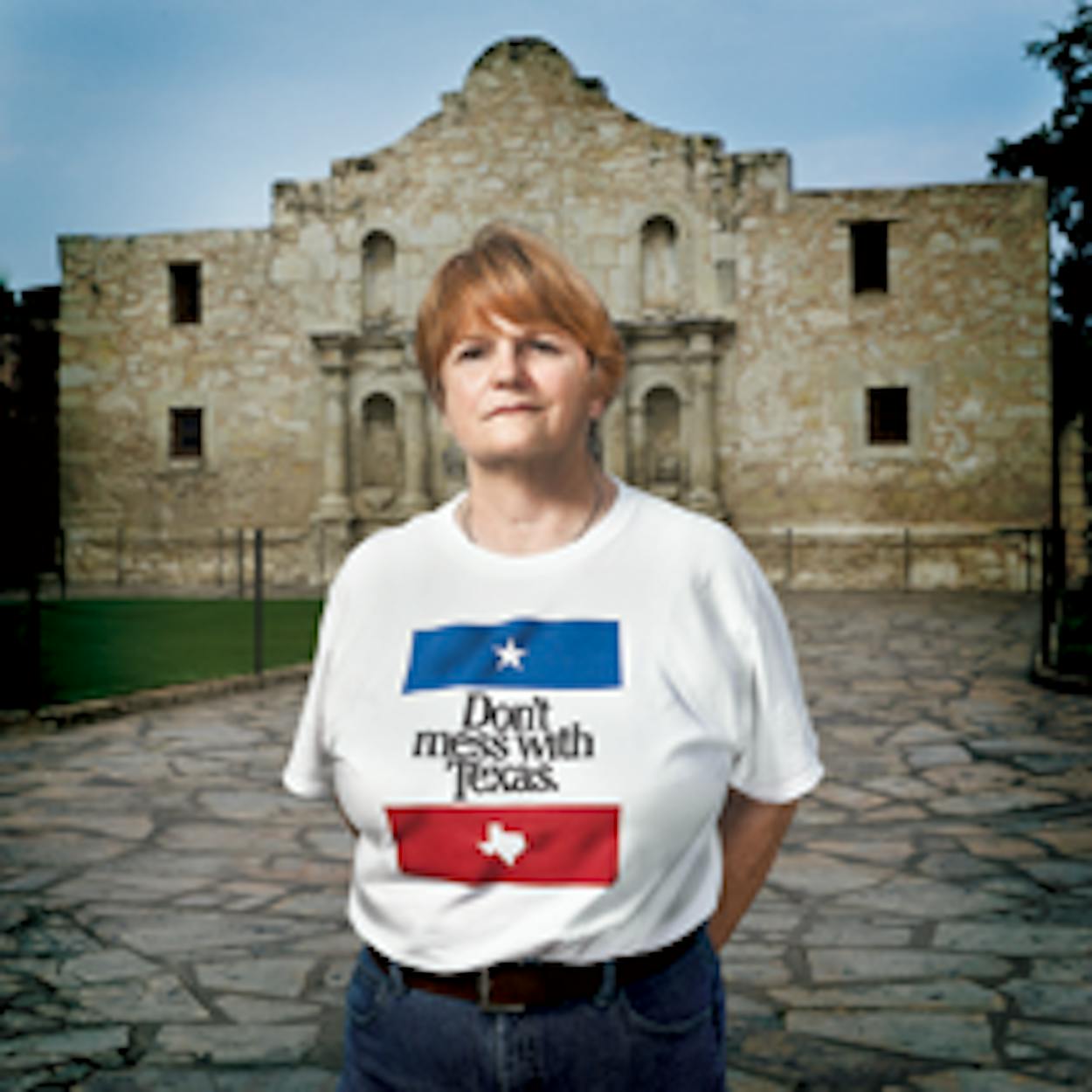

On a muggy morning in June, Sarah Reveley, a 65-year-old renegade member of the DRT, sat on the couch in her cozy bungalow in Alamo Heights, an affluent neighborhood north of downtown San Antonio. She was dressed in jeans and a “Don’t Mess With Texas” T-shirt. “I think the DRT is toast,” she said with a vintage Texas good-ol’-girl accent. “Nobody—not the governor, the attorney general, nor the Legislature—can ignore their mismanagement of the most revered historic site in Texas.”

Last fall, Reveley hunkered down with her computer in her study. Surrounded by books, financial documents, and minutes from DRT committee meetings, Reveley slowly compiled research. On February 1 she did the unthinkable: She formally requested that the DRT be removed as custodian. She filed a two-page official complaint with the attorney general’s office, with 34 documents attached, accusing the DRT of failing to preserve the Alamo. She went back through thirty years of master plans to outline the lack of follow-through on preservation efforts. Most damaging, she reported that the DRT had failed to act when a 2007 report identified leaks and cracks within the vaulted roof of the chapel. A few days later, small bits of plaster fell from the roof, and barricades were erected to protect tourists. “I may appear to be wacko,” said Reveley, a sixth-generation Texan of German descent, “but believe me, I am studious, and like my ancestors, I do not give up a fight.”

Van Cleave insists that the DRT has not neglected the roof. In July a new engineer’s report identified rainwater seepage into the chapel as the primary threat to the roof, not the cracks, and suggested that the 73-year-old copper, lead-coated exterior be replaced. “The roof has been and is now our number one priority,” said Van Cleave. “We have the money to fix it, and we’ll get it done.”

But it didn’t take long for the DRT to push back against Reveley. She received an official notice in late August that she too faces expulsion. Reveley said she won’t fight her removal, which would bring the total number of women expelled from the DRT during its entire history to four—three of them casualties of the current battle.

The line in the sand over who controls the Alamo was drawn in April, when state officials learned that the DRT had applied for a federal trademark to register the words “The Alamo.” From the isolation of the fortress within the Alamo’s compound, the idea made perfect sense. The Daughters weren’t trying to prevent the use of the words “The Alamo” for any of the thousands of businesses that utilize the name, from Alamo Fire Works to Alamo Cafe. The DRT wanted to trademark the words “The Alamo” so it could sell official T-shirts and merchandise. In late July lawyers for the state filed a brief with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office formally opposing the DRT’s application. In essence, Perry and his lawyers said, the Alamo belongs to Texas, not the DRT.

Though bills were routinely filed in the Legislature during the nineties to remove the DRT as custodian on the grounds that its interpretation of the Alamo’s history was racist, the culture wars hadn’t yet heated up and the group’s power was impenetrable. Now the iron grip of the DRT has weakened thanks to the latest round of controversies. Van de Putte, among others, may file a new set of bills in the upcoming session. One of two scenarios is possible. Either the insular culture within the DRT itself will have to change or the state could name a new custodian, such as the Texas Historical Commission. “We must protect the Alamo,” said Van de Putte. “I no longer have full confidence in the DRT’s ability to ensure the shrine’s structural integrity.”

Yet it may be difficult for some to imagine a future without the DRT. Many Texans have always viewed the Alamo through the organization’s lens or have projected onto it Wayne’s interpretation that it is a worldwide symbol of freedom over tyranny. Year after year, those who live in San Antonio see the Alamo as a combination of holy shrine, battle site, tourist attraction, and political carnival. They see the martyrdom of Bowie, Crockett, and Travis, as well as the Alamo’s shadowy side: the relentless pitting of Anglos against Mexican Americans, the obsession with blood lineage, and the confusion between sentimentality and realism.

If there is a change in the DRT, the two sides of the myth may at long last be resolved. What many Hispanics want is not a simple, one-sided story of Mexicans versus Texans but a more complete history. In 2001 independent filmmaker Jim Mendiola, a San Antonio native, and Rubén Ortiz-Torres, a contemporary artist from Mexico City, created an art installation that included two hologram prints of the iconic facade of the Alamo. As the viewer approached, the building slowly disappeared, as if it were an illusion. In many ways, the Alamo functions as a Rorschach test for Texans: What you see depends entirely on who you are.

Van de Putte, for example, is eligible by blood to be a Daughter herself. Like most Hispanics, she believed the John Wayne version of the Alamo’s story for most of her life. “It wasn’t until I was in college that I learned that Susanna Dickinson wasn’t the only woman who survived the battle,” said Van de Putte. “Eleven Tejano women and eight children also survived. Their history has been erased.”

How would someone like Lionel Sosa, an advertising guru who has designed political advertising campaigns aimed at Hispanic voters for every Republican presidential candidate since Ronald Reagan, explain the Alamo story? “Healing with Latinos is definitely possible but only when the full story is told,” said Sosa, a trim, elegant man with a gentle, soft-spoken demeanor. “The Mexicans were trying to get back the land they lost when the immigrant Texans reneged on their deal with Mexico. They were given the land in exchange for populating Texas, then decided it was theirs. Does that make them heroes? Most people who visit the Alamo today go home with the impression that the Mexicans were the bad guys and the defenders of the Alamo the good guys. There are no good guys or bad guys here, only the two sides defending their territories.”

Early one morning this summer, as the DRT readied its defenses, two hundred noisy teenagers, many with earbuds dangling from iPods, wandered around Alamo Plaza. They were from nearby YMCA camps, and about half were Anglo and the other half Hispanic. In other words, the group represented the population of Texas in the near future.

“It sure is small,” said one.

“Not much to see here,” said another.

Whatever the Alamo is or is not, it remains the central symbol of Texas, one of the places that define us. In the end, the current battle is about not only how the Alamo will be remembered but whether more than half of Texans will remember it at all. The fight—in 1836 and now—is for the future of Texas.