BACK IN THE FIFTIES, WHEN TEXAS was still a Democratic state and the party’s conservative and liberal wings fought bitter battles over issues like segregation and labor unions, it was often said that the Capitol, with its high ceilings and tall columns, was “built for giants but inhabited by pygmies.” That witticism long ago passed into oblivion, but it’s worth resurrecting for its architectural rather than political significance. Erected in the 1880’s to inspire the people’s representatives to be worthy of their workplace, the Capitol is our grandest public building. Its pink-granite exterior is rough and uneven and unyielding, rather like Texas itself, and its interior was meticulously restored a decade ago to its early-twentieth-century appearance. Now in its 119th year of service, it still fulfills the prediction of Judge A. W. Terrell at the dedication ceremony in 1888: “Whenever, in all time, a son of Texas shall behold its vast proportions, pride will come around him like a mantle and crystallize devotion to his State.”

As the Texas Legislature meets in regular session for the eightieth time, tens of thousands of Texans will descend upon the Capitol to watch our lawmakers at work. Some will come as supplicants, some as tourists, and some, like me, as observers and chroniclers. Buses from every city and town will unload the schoolchildren who sit in the House or Senate gallery and wait to be recognized by their elected officials. A legislative session is a great spectacle in a great setting; whatever visitors might think of the lawmaking process—often described by legislators themselves as the making of sausage—they can at least appreciate the edifice where it takes place.

The best way to do this is to take the 45-minute guided tour that is offered from eight-thirty to four-thirty on weekdays, with abbreviated schedules on Saturdays and Sundays. The tour service is located in the old treasurer’s office, just inside the south entrance (the cell-like bars that once protected the state’s money are still in place). You will visit the entrance hall, the rotunda, and the House and Senate chambers and finish in the underground extension, which was added in the nineties.

But the tour is only the beginning. There is much more to see if you know what to look for, and I’m going to tell you precisely that. I’ve been roaming the halls for 42 years now—5 as a staffer, the rest as a reporter—and I’ve come to know the building as a home away from home. My intention is to give you a sense not only of what you see but also of what you don’t see.

WE’LL START THE TOUR OF MY FAVORITE PLACES at the point where the guided tour stops: in the extension. Before you is an open-air rotunda that rises up to ground level. The nickname for this spot is the “shark tank,” so called because cell phone reception is not reliable in the extension’s subsurface corridors, and during the session, while committee meetings are taking place nearby, this small rotunda is sought out by lobbyists trying to transact business with their clients.

Before the extension was built, all 150 House members officed in the Capitol. Larger rooms were chopped up into warrens of tiny offices with makeshift walls and low ceilings that fostered a sense of claustrophobia; in some cases, half a dozen or more legislators would be housed behind a single door on the main corridor. As cramped as these quarters were, they enabled a sense of camaraderie to develop, because lawmakers were always dropping in to chat with their colleagues. The unforeseen consequence of building the extension was the decline of that camaraderie. It was evident in the first session after the extension opened, in 1993. All House members had individual offices with space for several staffers. When they weren’t on the House floor or in committee, they were closeted in their offices on long hallways, not schmoozing with other members. The loss of visiting time is one of the factors that has contributed to the increasing partisan divide in the Legislature. Members simply don’t know one another as well as they used to.

Next stop: the Capitol basement. Before the restoration, the ceiling was a maze of pipes and the wide corridor was narrowed by stacks of boxes and random pieces of discarded or broken furniture in transit to their final resting place. Notice the open space in the middle of the building. Many visitors know that standing on the star in the center of the rotunda on the main floor and speaking in a soft tone of voice will produce an amplifying effect; surprisingly, the same result occurs here too, notwithstanding the Italianate terrazzo floor above.

Today’s visitors can dine in a cafeteria in the extension, but before the extension existed, the only sustenance in the Capitol, other than in vending machines, could be found at a cheerless snack bar near the stairway on the House side of this basement rotunda. In those days, lobbyists took favored lawmakers off the Capitol grounds to private clubs—the Austin Club, the Deck Club, the Citadel Club—during the lunch recess, while the rest of us had to endure microwaved hot dogs and canned soups at the snack bar, whose sardonic nickname, inspired by the flooring, was the Linoleum Club. Its Formica tables and plastic chairs are memorialized in a sketch that is in the possession of the head of the tour guide service.

On the walls of the basement are composite photographs of the members of successive legislative sessions, senators and House members each on their side of the building. I have spent hours here looking among the individual photos for familiar names from the past. In the 1919 composite, on the bottom row, third from the right, Lyndon Johnson stares out at you. Actually, it isn’t LBJ; it’s Sam Johnson, his father, but the features—those ears! that nose! that squinty look!—are unmistakably those of the future president’s. Across the hall, in the 1911 composite, is Lyndon’s mentor, Sam Rayburn, the Speaker in Austin as he would later be in Washington. Baldness was a distinguishing feature of Rayburn’s, but in his 1907 photograph, he has a nice head of hair. By 1911, however, the hairline has severely receded, and by the time his official photograph as Speaker was taken, in 1913—you can see it in the Speaker’s Committee Room, just off the House chamber, on the second floor—he was bald. Another composite worth tracking down, in the hallway behind the House gallery, is the one from 1957. Look for the young Bob Bullock, just a freshman but already displaying the mirthless I-know-your-darkest-secrets grin that would make the blood of so many run so cold for the next 42 years.

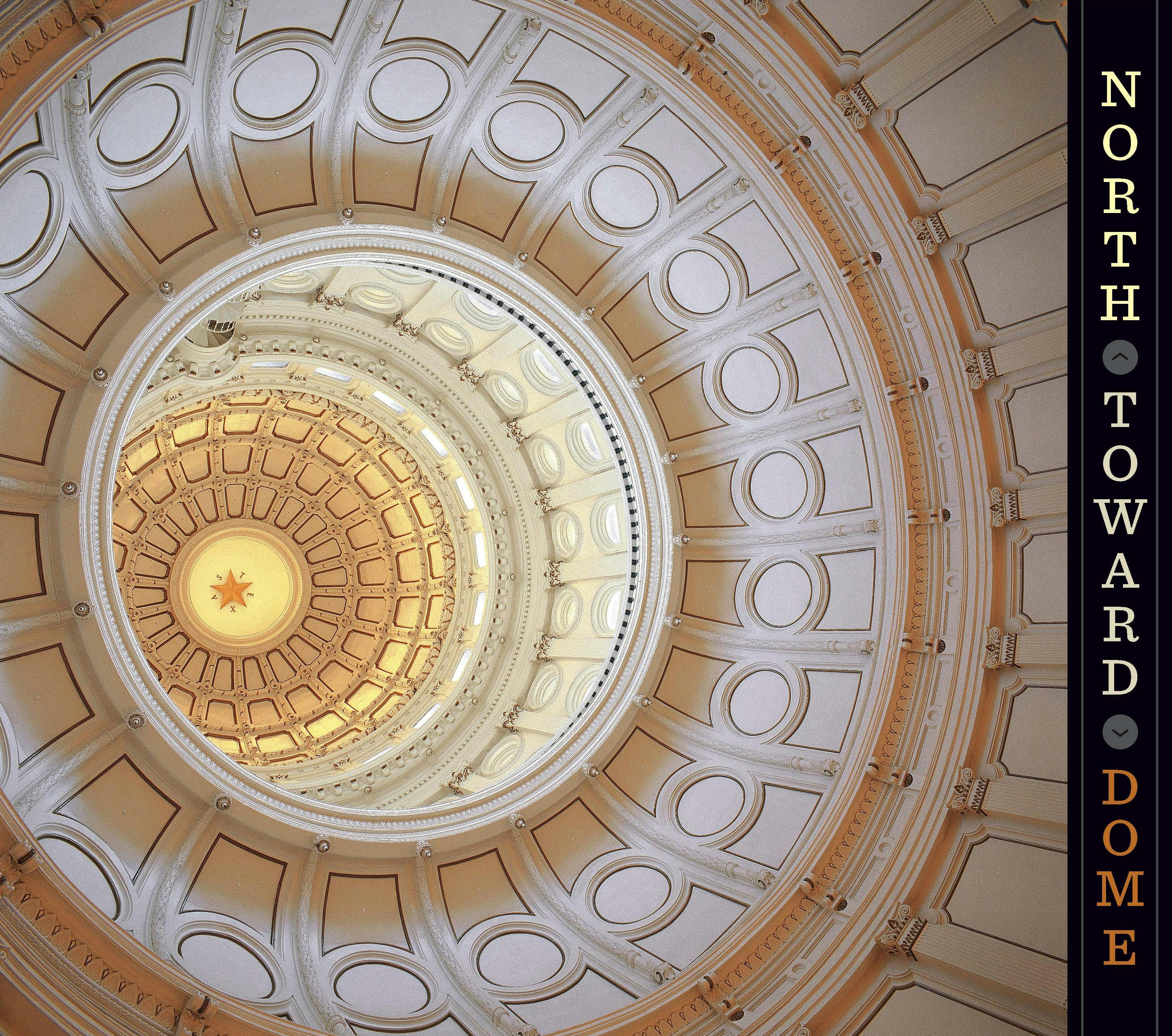

AT THIS POINT YOUR CHOICE is whether to start at the first floor and work your way toward the dome or start at the top and come down. Because the dome is such a focal point, start there, which means the fourth floor—the highest level most people are allowed to access. Many visitors ask about going higher, but the answer is no: It is a dizzying, difficult climb, which legislators (who are permitted to make the trek) have described to me as “hot” and “cramped.” You can get a sense of the challenging ascent from the narrow stairway—roped off—on the House side that leads upward to the fifth level, which is the last one that has a walkway around the rotunda. Then, from the Senate side, you can get a good look at the spiral staircase that goes up to the dome.

Actually, there are two domes, inner and outer. The inner dome holds the Texas star, situated 218 feet above the rotunda; the outer, much higher, is what you see from the street. Several more staircases must be negotiated to reach the “lantern,” a slender, columned cupola capping the dome, and the narrow exterior walkway that circles it.

I have never tried (or wanted) to make it to the top, but I do know someone who has made the trip. In 1997 state representative (now senator) Kyle Janek arranged with then-Speaker Pete Laney to take the woman he had been dating to the top of the Capitol. Laney’s wife, Nelda, had an aide put a small table with flowers and a bottle of champagne on the walkway outside the lantern. Spotting them, Janek’s date said, “We have to leave right away. Somebody is having a party”—and turned around to see Janek holding a ring. They returned to the dome to celebrate their second anniversary, with Shannon Janek cradling her new baby; now, she says, she’s not going back until all three of her children can make the climb.

Before you leave the fourth floor, walk over to the atrium in the north hallway. If it’s a sunny day, look up at the skylight for shimmering streaks of blue light. These are cast by 24 glass windows, known as oculi, with a white snowflake-like pattern. You can see a couple of them through perforations in a large hemispheric bauble hanging from the ceiling. Why the architect chose to put these gorgeous cobalt windows in a place where no one can see their full effect is one of the mysteries of the Capitol.

NOW START TO HEAD DOWNSTAIRS, after making the rounds of the rotunda, looking at the portraits of the governors as you go. Notice in the fourth-floor rotunda that portraits of early governors take up all but seven panels on the wall. After Rick Perry, that leaves room for just six more governors before the Capitol runs out of space. Assuming that Perry serves his full term, until January 2011, and that the six succeeding governors serve two terms each, Texas faces a portrait crisis around 2059.

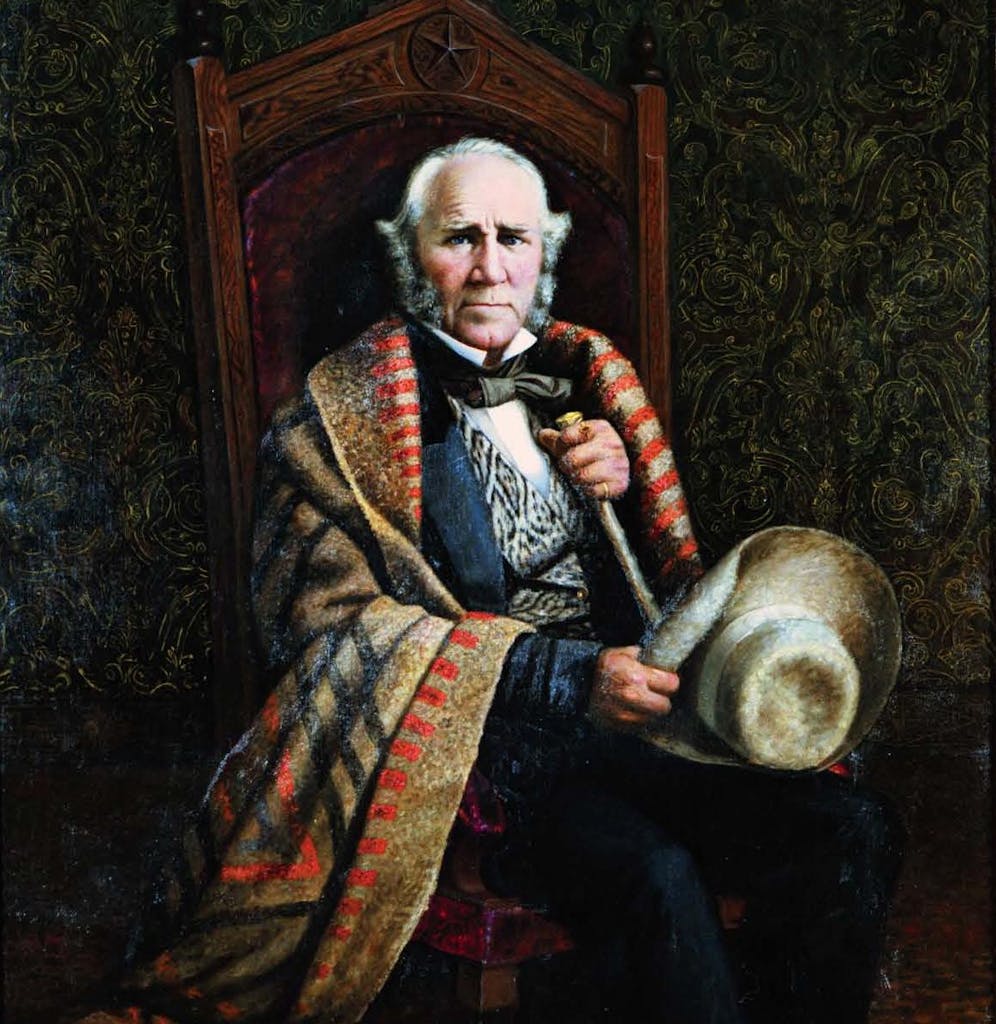

Every now and then, I like to take the time to look at each portrait. The last time I did this,

I came to the beginning of the Republic of Texas… but where was the portrait of Sam Houston, its first president? Later on, the mystery was solved. Houston’s portrait, without the Cherokee blanket draped over his shoulder that appears in another portrait in the Capitol, honors his election as governor in 1859 and also his two terms as president of the Republic. Okay, I’ll buy that, but then why does Miriam “Ma” Ferguson, the wife of the impeached James E. Ferguson, get two portraits for her two nonconsecutive terms while Sam warrants only one?

Few governors have been more obscure than S. W. T. Lanham, elected in 1902. Lanham was a congressman who came back to run for the statehouse and regretted it almost immediately. “Office seekers, pardon seekers, concession seekers overwhelmed me,” he said, describing himself as “broken in spirit.” A book called Governors of Texas, by the late Abilene and Austin newsman Paul Bolton, features sprightly two-page bios of Texas governors before 1950; the author describes Lanham’s portrait as revealing sadness in his eyes. To me, it seems more like a blank stare. The unhappy Lanham died soon after leaving office. Three portraits later, the disgraced James Ferguson casts an unrepentant gaze at passersby.

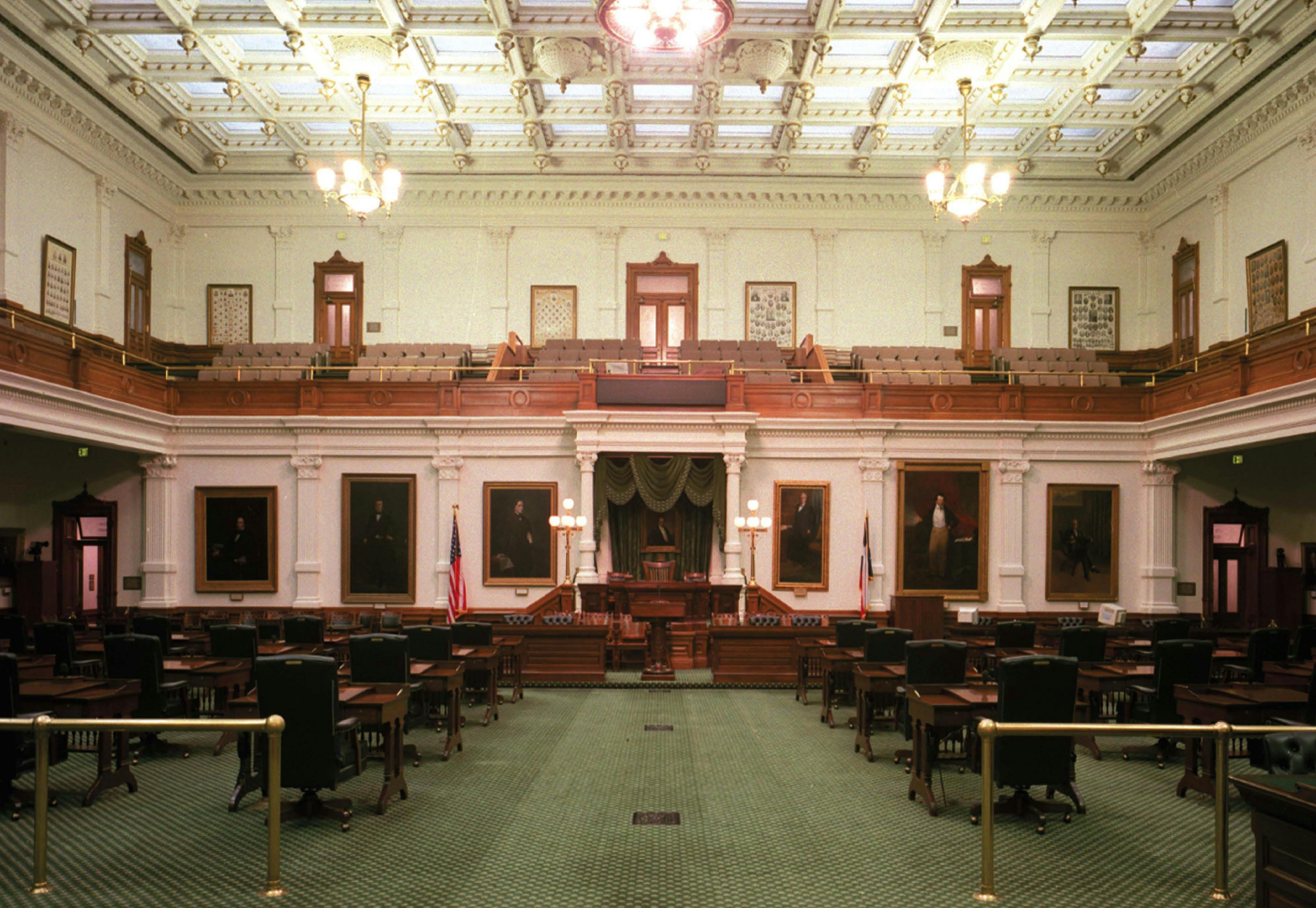

The third floor is mainly taken up by the House and Senate galleries. The House is crowded, noisy, unruly, and unpredictable. A long line of members waiting to speak at the back microphone indicates that a controversial bill is being debated; have a seat and watch the show. The Senate is sober and dignified. Its chamber was once described as resembling a mortuary parlor, befitting its role in the legislative process. On the way down to the second floor, take the House stairway as far as the landing between the floors, and an astonishing sight will come into view: a teeming mass of flesh packed into the area outside the chamber like cattle bound for market. Not a bad simile, because most of the people pressed up against one another are lobbyists, and who knows what they’re buying or selling or for what price.

Stand and watch for a moment. The lobbyists walk over to a desk and write down a representative’s name on a slip of paper, which is delivered to the rep inside. Keep your eye on the door to the chamber. In a minute or two or three, it will swing open and out will come the sought-after lawmaker. He’ll scan the area for the lobbyist who summoned him, and they’ll huddle against a column or a railing, out of the flow of traffic. Welcome to the abattoir, from whence sausage comes.

ONCE YOU ARE SAFELY ON THE SECOND FLOOR, walk into the Legislative Reference Library and head straight to the back wall. There you’ll see a handsome balcony but no door; the only egress is through a very large window. The Capitol has a number of concealed staircases, and one of them is in the library’s northwest corner. It’s behind a locked door that leads onto a small landing; you can glimpse it through clear spaces in an otherwise frosted glass panel. A smaller door in the wall at around shoulder level opens to reveal a cavity for a dumbwaiter. It was once used to send law books up to the Supreme Court, which met in an appropriately magisterial room above the library—now restored and viewable by the public, as is the former home of the Third Court of Appeals, across the hall—until both courts moved to an uninspiring building on the grounds northwest of the Capitol in 1959. See if you can locate an old wooden writing chair with a long arm in this part of the library. It was used by Santa Anna during the Texas Revolution.

Two more rooms on the second floor are open to the public. One is the Governor’s Public Reception Room. It has an odd chair for courting (two seats facing each other and connected by a single armrest), but I have never found this room as interesting as the other, the Lieutenant Governor’s Reception Room, known informally as the Great Room. To get there, take the passageway from the Senate floor to the hallway behind the chamber. At the other end of the hallway, a section of the modern wall has been removed to reveal, through glass, a segment of the original unplastered interior limestone wall. Some of the original furnishings in the Great Room were destroyed in a 1983 fire that started in the lieutenant governor’s apartment (the entire building could have been lost, as was the previous capitol in 1881). The Great Room has some of the best art pieces in the Capitol, including oils by Julian Onderdonk and Frank Reaugh (pronounced “Ray”), Texas’s version of Frederic Remington. Tim Mateer, who prepares food for receptions in the Great Room, is an authority on anything you might want to know about the room and will happily answer questions. The thing I love most about the Capitol is how Texan it is, on the inside as well as the outside. Even the way the state got the money to build it is a great Texas story; it sold a Chicago syndicate three million acres of state-owned land, which became the fabled XIT Ranch, along the western border of the Panhandle. As you walk the halls, on the second floor and elsewhere, you’ll notice that the builders found all sorts of ways to work Texas motifs into the design: lone stars, the outlines of the state map, even the state’s name in letters formed by lightbulbs in chandeliers high above the House and Senate chambers and etched into the door hinges. So coveted are those hinges by souvenir seekers that the state preservation board had to replace flat-head screws with two-holed screws that require a special tool to extract them.

Down on the first floor, most of the major features—the rotunda, the life-size statues of Stephen F. Austin and Sam Houston, the words and symbols in the terrazzo floor—are on the regular tour. But there is one thing you should be sure to see. In a nook behind the staircase leading to the Senate lobby is a plaque on the wall that most people who ply their trade in the Capitol don’t even know is there. “Children of the Confederacy Creed” it is titled, and it reads: “We … pledge ourselves to preserve pure ideals; to honor our veterans; to study and teach the truths of history (one of the most important of which is, that the War Between the States was not a rebellion, nor was its underlying cause to sustain slavery), and to always act in a manner that will reflect honor upon our noble and patriotic ancestors.” I don’t know which is harder to believe: that this plaque was erected as recently as 1959—or that it’s still here.

LADIES AND GENTLEMEN, this marks the end of your tour. Please be on the lookout for pygmies as you leave.