Our state may be changing at warp speed, but pockets of the past are everywhere— if you just look around. We’ve waltzed at dance halls and skated at roller rinks, sipped homemade root beer and even had our hair cut in search of the places and pleasures on the following pages. So slow down, turn off your cell phone and come along on a trip to days gone by.

ICEHOUSE

Looking for fruity little foo-foo drinks with paper umbrellas in them? Then JIMMIE’S PLACE is not for you. The beverage of choice here is beer. Cold beer. Cold bottled beer. That’s because Jimmie’s is a true icehouse, a distinctly Southern subtype of neighborhood bar that features an inside counter and outside tables and is especially prevalent in areas with sticky, icky weather—areas like the Heights in HOUSTON, where Jimmie’s has been reviving scores of wilted residents daily since 1950. How does it do that when, in classic icehouse tradition, it has no air conditioning? Well, cooling comes mainly from a quartet of sources: the canopylike roof over the picnic tables out front; the open garage-style doors, which facilitated truck-loading back when Jimmie’s sold more ice than beer; a couple of outsized floor fans, both orange because owner Frank Murray—son of Jimmie—was on Darrell Royal’s first-ever University of Texas football team, in 1957; and of course, the beer, which isn’t just refrigerated but submerged in ice, a practice that, regulars swear, makes it not only colder but tastier too. The heterogeneous clientele favors Budweiser and Miller longnecks; the interior decorator chose hardy-har-har bumper stickers and a giant inflatable crab. Jimmie’s Place, 2803 White Oak, Houston (713-861-9707). Anne Dingus

STEAKHOUSE

Picture a queen-size mattress atop a full-size frame. That’s the way your 22-ounce T-bone will look draped across the platter at the rattletrap LOWAKE STEAK HOUSE, a bastion of beef that was established in 1949 and is located some 28 miles east of San Angelo. (Actually, the tee-ninesy burg of LOWAKE—rhymes with “flaky”—is easier to find if you head southwest from Ballinger and avoid the zigzagging farm-to-market roads.) The tasty 22-ouncer is the medium-size T-bone, by the way; it comes with Texas toast, a salad-bar run, and a big ol’ baked potato and will set you back $18.95. The steaks—there are fourteen cuts to choose from—are unapologetically retro: griddled, not grilled. That’s just fine with the clientele, which at a recent Friday lunch was 85 percent male and arrayed variously in dress shirts (oilmen), T-shirts (truckers), and Western attire (ranchers). The left side of the menu offers non-beef items (chicken gizzards, for example), but why bother to come all this way and not down some cow? The decor consists of beer signs (one appears to depict George Washington contemplating a Jax), a dozen or so sets of cow horns, and an 1892 dehorner that resembles a nutcracker on steroids. Lowake Steak House, FM 1929 and Texas Highway 381, Lowake (915-442-3201). A.D.

ROADSIDE PARK

Politically correct they’re not. But the three TEPEE SHELTERS along the scenic River Road between Presidio and Lajitas in Big Bend are popular sites for picnics and for taking in the dandy view of the winding Rio Grande. Built of steel and plaster in 1967, the tepees shade rock tables—and stand as icons of a mythical Wild West that still captures the imagination. Tepee roadside park, south side of the River Road (Ranch Road 170) ten miles southeast of Redford. Kathryn Jones

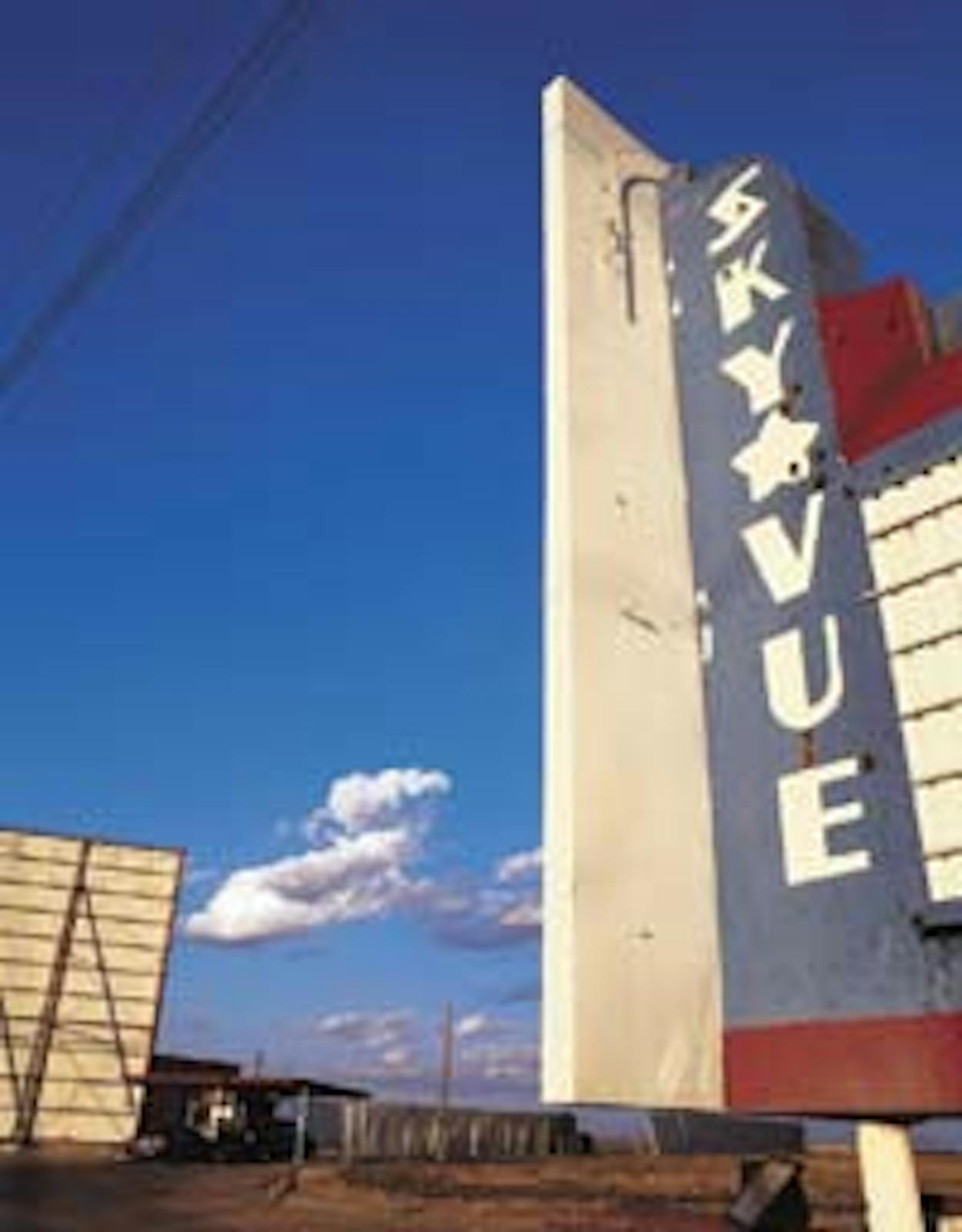

DRIVE-IN THEATER

At first glimpse, with the sun still high, the SKY-VUE DRIVE-IN THEATRE was distinctly unprepossessing— after all, it’s been here in Lamesa (“La-mee-sa”) since 1948. Of course, there’s not much to any drive-in theater (Texas now has only a dozen or so) other than a gravel parking lot, rusty trash barrels, and the looming screen. But as dusk fell, the Sky-Vue was transformed into quite a social scene. While waiting for Shrek to start, boys tossed footballs, children squabbled over the swings, families lined up lawn chairs, and high-school honeys smooched in pickup beds facing the screen. Part of the attraction for locals is the concession stand, housed in a cinder-block building; the specialty is the Chihuahua, a sandwich of two crisp corn tortillas enclosing chili, melted cheese, and fresh onion and cabbage—messy but good. Be warned that the munchies attract flies, which are a problem because moviegoers opt, in time-honored fashion, to leave their car windows down, even though tuning the radio to FM 91.9 has replaced using the outdated hook-on speakers. Finally, the theater lives up to its name: Overhead I spotted the Big Dipper and Scorpio among a plethora of non-Hollywood stars. Sky-Vue Drive-in Theatre, just south of town on U.S. 87, Lamesa (806-872-7004); Friday, Saturday, and Sunday nights; $4 per person. A.D.

FRIED PIES

Most mornings, Shirley Rooney and her daughter Francene Taylor rise before sunup to start making fried pies. Rooney, a former longtime cook at the Gage Hotel, has been making them for years. But it wasn’t until she opened SHIRLEY’S BURNT BISCUIT BAKERY—“the best little bake shop west of the Pecos,” as she calls it—in May 1999 that she discovered just how much folks still like the old-fashioned treats. Now Rooney, a wavy-haired, bespectacled 66-year-old who usually has a black apron tied around her waist, and Taylor often fill special orders for dozens of fried pies. They sell only three flavors—peach, apricot, and apple—for 75 cents each. The hole-in-the-wall bakery, on MARATHON’s main drag just a block from the Gage, also makes brownies, cookies, polvorones (Mexican wedding cookies), banana nut and zucchini bread, cinnamon rolls, and of course, biscuits. I’ve logged hundreds of miles (and consumed thousands of calories) researching fried pies, and the Burnt Biscuit’s—lusciously stuffed with fruit, deep-fried in vegetable shortening, and dusted with sugar—beat the competition hands down. What’s Rooney’s secret for the perfect pie dough? “Well, for years I didn’t get it right,” she says with a laugh. “And then I discovered that it’s ready when it feels like a baby’s bottom.” Shirley’s Burnt Biscuit Bakery, 506 E. First (U.S. 90), Marathon (915-386-9020). K.J.

FIVE-AND-TEN

At the VARIETY FAIR 5 & 10 in Houston, the variety is more than fair—it’s fantastic. Crammed inside 2,500 square feet is a wondrous hodgepodge of merchandise, from candy and cosmetics to paper dolls and party hats (including lampshades!). Exactly how many items stuff the store is uncertain: “You and I do not know how to count that high,” says 47-year-old Cathy Irby, whose parents, Ben and Alice Klinger, launched Variety Fair in 1948. The five-and-ten lives up to its name—you can get, say, a tiny paper replica of the Texas flag for a nickel or a miniature plastic hot dog for a dime. Inevitably, in these costly times, most wares will set you back a bit more, but you’ll still find plenty of good deals, including a few things that you haven’t seen in years (or, depending on your age, that you haven’t seen, period). As a test, I ask Irby if she stocks those little gizmos your grandma used to stick in the top of a water-filled Coke bottle to dampen her ironing. “Got it!” Irby says with a grin, holding up the $1.39 laundry sprinkler, then adds, “It’s plastic, though; you can’t get the cork-and-metal kind anymore.” Other delightful throwbacks include a spool of “darning cotton,” $1.39; a $1.59 “bra extender,” in case your bust exercises are doing the trick; and name-your-color hairnets, like the beaded Jacqueline Decorated Glamour style in black for 89 cents. One of the store’s charms is its practice of retaining and selling old merchandise—without updating the price tag. Thus, you can score Ghostbusters gum for 39 cents or a plaster wall plaque (your choice of swan or fruit motif) for $2.99. But the real bargain here? Time travel, absolutely free. Variety Fair 5 & 10, 2415 Rice Boulevard, Houston (713-522-0561). A.D.

CHICKEN-FRIED STEAK

The big draw at BILL AND ROSA’S KK STEAKHOUSE AND SALOONIN D’HANIS is the chicken-fried steak, the state’s number one favorite fried meat. At a weekday lunch recently, eleven other diners within discreet peeking distance were forking up bites of CFS. My younger son, Parker, boldly took on the full-pounder ($13.99) for three reasons: He loves chicken-fried steak, he’s a teenager with the requisite Texas-size appetite, and his brother bet him $2 that he couldn’t finish it. But he did, despite its being roughly the size of an issue of Texas Monthly but considerably thicker. The $4.95 lunch special was a mere TV Guide-size portion but had the same tender meat, crisp, ungreasy crust, and peppery cream gravy (with mashed potatoes, a vegetable, and salad on the side). Said our sassy blond waitress to Parker when she brought the check: “You gonna take a nap now?” Replied Parker: “Zzzzzzzz.” Bill and Rosa’s KK Steakhouse and Saloon, 7400 County Road 525, one block north of U.S. 90, D’Hanis (830-363-7230). A.D.

ROLLER RINK

When I told my mother that I was going to visit a roller rink in SAN BENITO that was built in 1947, she immediately declared it to be the same one she had gone to when she was a little girl. The adobe-brick-and-wood building, which was the venue for a performance by a young Johnny Cash in 1958, still has the original wood floor (give or take a few boards). The new stuff? Flashing disco lights instead of flags hanging from the ceiling and, since 1985, air conditioning. Cynthia and David Cook bought the rink three years ago from Cynthia’s parents, who had taken over from the original owner back in 1971. The Cooks have kept things simple. Admission is $4.50, which includes quad-skate rentals (kids can bring in their own quad or in-line skates). A bag of popcorn or a one-ounce cup of frozen pickle juice—a new item—is 25 cents. Of course, the action is on the rink, where kids still do the hokey pokey and the chicken dance. David has prerecorded most of the pop music, but you can request a tune at no charge, and for 50 cents you can dedicate a song to that special someone. Skate Center of San Benito, 944 E. Stenger, San Benito (956-399-6500). Patricia Busa McConnico

BAR

There are no last names at the DEEP EDDY CABARET, a friendly tavern just south of Austin’s well-heeled Tarrytown neighborhood. Most nights the line between friends and strangers, customers and employees starts to blur. Becky, Inger, Ralphie, Jack. Some customers have been coming in for close to thirty years and can justify the “Cabaret” in the Eddy’s name by recalling the two-week topless experiment in the seventies that ended when the regulars complained that their old ladies were going to make them stop swinging by. Others don’t know if the bar opened in ‘51 or ‘91 (the former) or who the pretty lady is in the photograph behind the bar (the Eddy’s late matriarch, Mickey) or why the place banned cell phones for so long (because of Andy’s pacemaker). On a recent evening the Monday bartender played dominoes with a couple of regulars while the Sunday bartender kept score and W. C. Fields fell down on TV. “We give some people names to show how they’ve chosen to waste their lives away from the Eddy,” said Yuri. “UT Jerry, Motorola Bob ” “That’s ‘ex-Motorola Bob!’” said Bob as he slammed down a double five. “Gimme a dime, Susan.” The more things change, the more the Eddy stays the same. Deep Eddy Cabaret, 2315 Lake Austin Boulevard, Austin (512-472-0961). John Spong

CATFISH PARLOR

Build a friendly, family-run restaurant, put down-home Southern-fried catfish on the menu, and you’ll have customers hooked for generations. That’s certainly true of CATFISH HILL, a little bare-bones place off a country road in GARFIELD, just east of Austin. It was opened in the late sixties by Clarence Washington, a sharecropper’s son who was born in Bastrop in 1913. When Washington died, in 1987, his son Alvin took over. Today Alvin, his wife, Barbara, and their daughter Vanessa still serve just-caught catfish (from one of the little ponds on the premises) every weekend, fried whole (but headless) in a delicate cornmeal crust, with standard sides like coleslaw and hush puppies ($8.50). “Some people have been coming here for thirty years,” says Alvin. “And they come from all over.” Handwritten entries in a notebook on the counter attest to that. Austin’s notable, quotable J. J. “Jake” Pickle is a longtime fan. In a letter congratulating the elder Washington on his seventieth birthday, the then-congressman wrote, “May the Lord keep and bless you both and may the catfish farm go on forever.” Amen to that. Catfish Hill, 5100 Wolf Lane, Garfield (512-247-2528). Open Friday and Saturday nights from 6 to 10. Eileen Schwartz

DANCE HALL

Texas has no shortage of venerable dance halls with that classic honky-tonk look and good live music. The special appeal of PORT ARTHUR’S RODAIR CLUB is authentic Cajun music in a genuinely funky, no-frills setting—the kind big-city folks find so endearingly quaint. A waitress named Dolores serves you a beer with a smile, while the other customers make it clear that you’re among friends. The Rodair takes pride in its Texas Cajun culture, handed down by local descendants of French Canadians who originally settled in Louisiana. Sadly, the Cajun culture in Texas has begun to fade. “When I tell people I’m Cajun, they say, ‘I thought that was a spice,’” says Kara McCaw, a 24-year-old bartender at the Rodair whose grandparents Joe and Dioris Thibodeaux began holding Cajun dances at the little club on a rural highway in 1965 (it was originally built as a rock and roll venue in 1957). Live bands play that distinctive, spirited Cajun sound (typically accented by an accordion and a fiddle) on Saturday nights. Couples waltz and two-step on the beautiful oak floor, and everyone dances with the little kids. The Rodair Club, from U.S. 287 near the Jefferson County Airport in Port Arthur, take FM 365 southwest for about six miles (409-736-1721); $4 cover charge. E.S.

HARDWARE STORE

Randy Carter leads the way through the CARTER-IVY HARDWARE COMPANY, the store his great-grandfather, T. S. Carter, founded in WEATHERFORD in 1902. A fourth-generation Carter, he began working in the store forty years ago, when he was five. “My granddaddy had me down here marking prices on hoe handles with a grease pencil,” he recalls. The two-story brick building, with its high wood-slat ceiling, pine floors, and jammed shelves, is a true hardware store. Old Winchester shell boxes line the long shelves and hold assorted clamps. Revolving wooden storage bins, also original fixtures, hold screws, bolts, nuts, and washers. Name an obscure part—for a windmill, water well, treadle sewing machine—and chances are Carter can go right to it. In addition to hardware, he stocks crockery dishes, weather vanes, butter churns, chicken feeders, oil lamps, and iron cookware to round out the product line. And although he sells popular modern tools, like Makita power drills, he also still offers “people-powered tools” like reel lawn mowers. But you won’t see a computer. The store keeps track of its sales the old-fashioned way. Money goes into a 1910 cash register. Receipts are handwritten. Charges are recorded by hand on ledger cards. Says Carter: “We’ve had ranchers whose families have had accounts here for almost one hundred years.” Carter-Ivy Hardware Company, 120 N. Main, Weatherford (817-594-2216). K. J.

HOMEMADE ROOT BEER

The best deal in Texas for a dollar is a mug of freshly made root beer at SCHILO’S in SAN ANTONIO. Sweeter than a stolen kiss, this dark amber brew comes to your table in a frosted mug with an inch of foam on top. The first sip puts you in mind of Norman Rockwell, Little League teams, and oompah bands in the park on Sunday afternoons. Should you happen to visit Schilo’s on a Friday or Saturday night and work up an appetite listening to the lederhosen-clad accordionist sing “Ghost Riders in the Sky” in German, supplement your root beer with one of the deli’s sausage plates and a cup of its nonpareil split-pea soup, which it has been serving since it opened in 1917. Schilo’s, 424 E. Commerce, San Antonio (210-223-6692). Patricia Sharpe

FARMERS’ MARKET

The season’s colorful harvest is piled high on simple wooden tables inside this open-air market. When I visited in June, I couldn’t resist the fat, juicy blackberries just brought in that morning, baskets of ripe red tomatoes, and Parker County’s famous peaches (the annual peach festival in July draws thousands), not to mention the locally grown watermelons, which were featured at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. In WEATHERFORD, located about thirty miles west of Fort Worth, buying and selling the bounty from nearby fields and orchards has been a central part of life for decades. At first farmers brought their wares in horse-drawn wagons to the courthouse square. Then, in 1940, the federal Works Progress Administration built the town’s simple but striking Public Market building, with its arched doorways and stucco facade. Nowadays the Public Market is operated by Dunn Produce and buys mostly from wholesalers. That arrangement drove the local farmers to raise about $45,000 in 1988 to build a separate farmers’ market—almost exclusively for produce grown in Parker County—on the other side of the parking lot. About twenty farmers regularly sell at the market, which is open daily and, with prices like $5 for three big, perfectly ripe cantaloupes, is a buyer’s market too. Weatherford Farmers Market, 217 Fort Worth (U.S. 180), Weatherford (817-594-1273). K.J.

SADDLEMAKER

West Bros. Saddlery, about six miles west of Center in the East Texas Piney Woods, is a throwback to the days when saddlemakers did all their work by hand. Pattern pieces hang on the walls. A tree stump with holes carved into it holds tools for cutting leather. The smells of leather and saddle soap permeate the plain, utilitarian space. The small custom saddlery, in business since 1978, has had its share of fame recently. Last fall West Bros. won a “best of show” award at the annual Boot and Saddlemaker Round-Up in Brownwood. That caught the attention of the Texas Young Republican Federation, which in September commissioned a custom saddle as an inaugural present for George W. Bush. While it takes about six days to make a relatively plain saddle, the Bush saddle took nearly three hundred hours—and cost $12,000. Says Troy West: “We’re tickled to get to do it for a president.” Troy walked me through the painstaking process of making a saddle by hand. Brother Danny builds each saddle’s “tree,” as the underlying framework is called, by carving the shape out of a pine block. Then Troy cuts, stitches, and assembles the saddle’s leather pieces, tools it with intricate designs, and finishes it with silver that he engraves himself. “Most saddlemakers buy the trees and the silver,” Troy explains. “We do it so it’s all custom.” West Bros. Saddlery, 5536 Texas Highway 7 West, Center (936-598-2627; westbrossaddlery.com). K.J.

MOVIE THEATER

The things I do for this magazine—like sitting through the latest Sylvester Stallone machismo movie. But even the noisy and noisome Driven was dramatically improved by being screened in the charming little ODEON THEATRE, a fixture on MASON’S wonderful town square. The marquee’s curvy art deco lines, outlined in deep pink neon, and the claustrophobic ticket booth haven’t changed since 1928, when the theater was built. The world premiere of the Disney classic Old Yeller, based on the great dog story by Mason homeboy Fred Gipson, made the Odeon famous in 1957, and today a community volunteer group is restoring it bit by bit; there are water stains on the ceiling and plaster is missing from the walls, but the seats, screen, and sound system are all nice and new. Before the show, forty or so folks—about a fifth of the seating capacity—enjoyed affordable snacks from the tiny concession stand; some candies are only 75 cents, and the most expensive item is the $2 “double dog,” a bi-wienie treat. Odeon Theatre, 122 Moody, Mason (915-347-9010); Fridays at 7:30 p.m., Saturday through Monday at 7; $4. A.D.

BARBERSHOP

“You’ve got hair like Jason Robards,” Louis Ayala tells me shortly after I settle into his chair. Stepping into Ayala’s Fort Worth barbershop, you get the feeling it hasn’t changed since he first started cutting hair more than half a century ago. Whole families sit in the church pews against the wall, reading magazines or playing while they wait. A huge poster of Ayala’s nephew Paulie, the world champion boxer, adorns the wall along with photos of friends, family, and regulars. An older woman sitting inside the front door tends to a portable oven filled with homemade tamales. The 72-year-old Ayala works alongside Mary Moore and Floyd Rivera, his business partner, who started out as the shoeshine boy before Ayala sent him to barber school in 1955. As Ayala works on my hair, we exchange idle chitchat punctuated with laughs and yessirs; when he’s finished, he removes the chair cloth, shakes it out, and produces a mirror so I can inspect my $8 haircut. Then he pulls out a photo album with snapshots of himself with Robards, when he cut the actor’s hair during the filming of 1987’s Breaking Home Ties in Dallas. My cut is even better than his. Yessir. Ayala’s Barber Shop, 1537 North Main, Fort Worth (817-626-1672). Joe Nick Patoski

MINATURE-GOLF COURSE

Miniature golf may be the realm of windmills, concrete dinosaurs, and other gimmicks, but at Cool Crest, such accoutrements would just get in the way. It was all about the game for Harold Metzger, a trucker who built Texas’ oldest and best mini-golf course in 1937 after he’d played a round at the Wee Saint Andrews in Dallas (now long gone) at the height of the mini-golf craze. The two-course, 36-hole layout emphasizes skill. Metzger chose the hillside location—a chip shot from Interstate 10—to catch the summer breezes blowing in from the southeast. Before air conditioning, there wasn’t a cooler place in San Antonio this side of the neighborhood icehouse. Today it’s the retro look that draws the crowds. The immaculate grounds—a tropical oasis with ponds, fountains, babbling brooks, banana and papaya trees, palms, and exotic flowers—maintained by Metzger’s wife, Ria, live up to the course’s motto: “Always Cool and Shady.” Cool Crest Miniature Golf Course, 1400 Fredericksburg Road, at Louise (exit 567B off Interstate 10), 210-732-0222; $4 per round. J.N.P.

CAESAR SALAD

Today you can waltz into any restaurant, cafe, or diner in the state and order a so-called Caesar salad. But those of us who can remember back a dozen or more years ago know that a real Caesar salad is never prepared in advance and is never loaded down with grilled chicken, shrimp, pumpkin seeds, tortilla strips, carrot curls, polenta croutons, or other extraneous nonsense. To have a pure and properly theatrical Caesar salad, the way it might have been prepared at Caesar’s Palace in Tijuana, Mexico, where the celebrated dish was invented in 1924, you must visit the Old Warsaw in Dallas. Here such things are done right and have been since the restaurant opened in 1948. The ceremony begins when a tuxedo-clad waiter arrives at your table with a rolling cart bearing a wooden salad bowl, chilled romaine, small silver dishes filled with Parmesan cheese, a lemon half, an egg, croutons, garlic, and anchovies, plus Worcestershire sauce and black pepper. He mashes the anchovies and garlic and, with great panache, cracks the egg and squeezes the lemon into the salad bowl. Then, amid much clacking of wooden spoons, he performs various feats of prestidigitation with the lettuce and remaining ingredients and ceremoniously places in front of you and your companion chilled white plates of honest-to-god Caesar salad. For a mere $12 for two, you have witnessed one of our culture’s vanishing rituals—and you get to eat the results. Old Warsaw, 2610 Maple Avenue, Dallas (214-528-0032; theoldwarsaw.com). P.S.

FRIED CHICKEN

In 1959 my family (mother, father, two brothers, and I) made a special trip from Austin to San Antonio to visit the Alamo and see Ben-Hur, an overwrought biblical blockbuster that was the Titanic of its day. We stayed at the historic Menger Hotel (big attraction for us kids: an irascible talking parrot in the lobby), and we ate lunch at my parents’ favorite restaurant, Earl Abel’s. Its streamlined forties look made us feel ultrasophisticated, and its all-American menu was like cafeteria fare, only better. For dinner, we all ordered the restaurant’s famous fried chicken: tender, juicy meat with a crunchy batter coating and “crackling gravy” that included crisp, salty scrapings from the bottom of the pan. When I recently made a sentimental journey to try the chicken again, it had not changed one iota, and although at $5.75 to $7 a plate it cost more than it did 42 years ago, it was still an old-fashioned bargain. Earl Abel’s, 4210 Broadway, San Antonio (210-822-3358). P. S.

GENERAL STORE

With an art deco stucco facade that sports the name “Weinzapfel” in raised letters, the Windthorst General Store stands out in this small dairy community a few miles east of Archer City. Native son Joe Zotz, 57, who owns the store with his partner and son, Russell, told me that the name on the facade refers to the family that established the original store in 1892 on another site in town and built the current structure in 1921. Zotz bought the store more than eight years ago after it had become run-down. He cleaned it up but left the original pressed-tin ceiling, pine floor, wooden counter, old scales, and hand-operated elevator for lowering heavy merchandise into a storage cellar. “Mr. Weinzapfel told me he used to buy two hundred sacks of flour at a time,” Zotz explained.While the store sells everything from Levi’s jeans and Wolverine boots to food, farm implements, hardware, washboards, and vet supplies like Udder Butter, Zotz has had to make a few concessions to modern times. Instead of cutting red-rind cheese by hand, for instance, he stocks packaged cheese because it keeps longer. It seems like a small thing, though, in a store that’s one of the last of its kind. Windthorst General Store, intersection of U.S. 281 and FM 174, Windthorst (940-423-6205). K. J.

BURGER STAND WITH CARHOPS

Veteran carhops who call you “hon” while taking your order, heavenly hamburgers (a thin meat patty on a lightly grilled bun with tomatoes, onions, pickles, shredded lettuce, and mustard, $2.35), and sublime root beer made on the premises and served up in frosted mugs (85 cents) make you feel like a king at the Prince of Hamburgers, a twenties-era establishment on a commercial strip two blocks west of the Dallas North Tollway. Shaded by its red-and-white-striped canvas awning, you can dine in the comfort of your car on everything from chili to fried pies. Turn on your lights for service. Prince of Hamburgers, 5200 Lemmon Avenue, Dallas (214-526-9081). J. N. P.

SODA FOUNTAIN

The hardy little Nederland pharmacy has endured for exactly one hundred years, and its soda fountain is such a local institution that it now takes up almost half the premises and boasts its own name, Nederland Lunch Counter. Outside, the brick mercantile is painted a soft buff with red trim, and the tidy but faded lettering helps the building retain its been-there-forever look. Inside, the centerpiece of the soda fountain is the original counter, elaborately inlaid with tiny square tiles of black, white, tan, orange, and aqua; on the shelves behind it are an ancient cash register (just for display), miscellaneous notes (“Call Shirley with pie count!”), and a collection of dishes including fluted sundae glasses and babies’ tippy cups. The menu is basic cafe fare, but the grill artist ignores standard meal parameters; he’ll cook you eggs or pancakes any time of day, and he cheerfully fixed me a hamburger at ten in the morning (hey, I’d been up since five). Favorite classic treat: a root-beer float. Favorite moment: overhearing the waitress ask another customer, “You want those biscuits regular or grilled?” Sated, I moseyed into the drugstore half for some ibuprofen (hey, I’d been up since five). Besides modern health and beauty items, you’ll spot plenty of evidence of the store’s past, such as an antique oak case with retro medicines like “German powder wafers” and “dentalgia drops.” If you have any questions about the store or Nederland in general, ask pharmacist Kenneth Sheffield, who’s worked there a mere 54 years. Nederland Lunch Counter, 1100 Boston Avenue, Nederland (409-729-3807). A. D.

MENUDO TO GO

“Menudo para los crudos” (“Menudo for hangovers”) goes the old saying, so it’s no surprise that the tripe-and-hominy stew has long been a weekend-only specialty at Mexican restaurants all over the state. In fact, so popular is menudo—even for the headache-free—that many places provide take-out service for families who bring their own containers (and who thus keep their houses free of the strong smell of cooking tripe). In El Paso the original Delicious Mexican Eatery has been dishing up its garlicky, chile-spiked menudo for neighborhood regulars since the mid-seventies. Says manager Velia Apodaca: “People bring in cooking pots, Crock-Pots, all kinds and sizes of pots. We charge by the scoop—two dollars a sixteen-ounce scoop.” The Delicious cooks its menudo all night long, so it’s tender and tasty by morning—just about the time those jackhammers are starting up in your skull. Delicious Mexican Eatery, 3314 Fort Boulevard, El Paso (915-566-1396). A. D.

HOMEMADE PIES

Pie are square, according to some folks; it’s a dessert that will never have the glamour of tiramisu or crème brûlée. But since chuck-wagon cooks and the like rarely had the milk and eggs required for cake baking, pie reigns as the most venerable of Texas sweets. And the choices at Utopia’s temple of pie-ety, the Lost Maples Cafe, would alone explain the town’s optimistic name. For two bucks a slice (a sixth of a pie), you can sample eight kinds, all handmade daily in the cafe’s kitchen: coconut cream, the best-seller; hard-to-find, supersweet buttermilk; two meringue choices, a non-tangy lemon and a creamy chocolate; classic pecan, apple, and cherry; and the crunchy, fudgelike chocolate-pecan. All go well with a hot cuppa joe. The pastry crusts are especially admirable, flaky and hand-fluted. There’s an extensive menu of fried stuff too, if you want an entrée to follow your dessert. The seating includes cedar benches as well as vintage dinettes, and the walls are decked with rusty farm implements and old advertising signs, as is entirely fitting—which your shorts won’t be when you depart. Lost Maples Cafe, Main Street, Utopia (830-966-2221). A. D.

POST OFFICE

The filling station burned down in the eighties, the cafe is now a storage shed, and Freitag’s General Store was sold several years ago to a Houston antiques dealer who stripped the 1880 mercantile to its bones and sold off its character to the highest bidder. But you can still detect a heartbeat in the tiny town of Kenney—at the diminutive post office, relocated from Freitag’s store to the Kenney State Bank building, built in the early 1900’s. Customers don’t have to wait in line—much less take a number—whether they’re buying stamps or picking up a dozen eggs from postmaster Katherine Johnson’s mother’s hens. Locals regularly stop by to drop off used paperbacks, spread the word that they need a deck built, or catch up on gossip with relief postmaster Norma Richter. “We had to build a wheelchair-accessible ramp a couple of years ago,” says Richter, “but hardly anybody uses it. We have one handicapped customer and she just drives up and honks and we go out to the car to take care of her.” U.S. Post Office, 707 Loop 497, Kenney (off Texas Highway 36 between Brenham and Bellville), 979-865-5197. Suzy Banks

VOLUNTEER FIRE DEPARTMENT BARBECUE

In the tiny town of Shelby, near Brenham, the volunteer fire department has been putting on two annual barbecues, on Memorial Day and Labor Day, since 1958. The May feast benefits the fire department, while the Labor Day event is for the town’s historic dance hall, Harmonie Hall. Usually anywhere from eight hundred to one thousand meal tickets are sold for each one, at $6 a pop. In addition to the beans and other sides donated by local supporters, the barbecue committee generally cooks up eight hundred pounds of beef and an equal amount of pork.

The committee is serious business. “You are either born into it or married into it,” says Brian Powell, who mans the five oak-wood pits with his father-in-law and seven others. The day before the event, the crew seasons the meat (salt, pepper, and spices), then, around one-thirty in the morning, puts it on to cook. About nine hours later they start pulling off the meat, and when the job is done, they head home to clean up for lunch. After the meal—and before a local polka band tunes up for dancing—everyone sits on folding chairs on the covered patio and sips cold beer or soft drinks while an auctioneer rattles off item after item: a stained-glass window, home-baked oatmeal-raisin cookies, a handmade whip. In May, when the proceeds go for necessities ranging from pagers to fire trucks, the most coveted purchase is always a quilt stitched by Lydia “Granny” Weinert. This year’s went for $1,000—but, hey, it’s for a really good cause. Shelby Volunteer Fire Department Barbecue, Harmonie Hall, FM 389 at Voelkel Lane, Shelby (979-836-9625). P. B. M.

AMUSEMENT PARK

In this Disney-Universal-Six Flags World of multimillion-dollar theme parks, it’s nice to know there’s still a family-owned summer place like Wonderland. Fifty years ago Paul and Alethea Roads opened Kiddie Land, as it was then called, in Amarillo’s Thompson Memorial Park. Over the years the couple has expanded the spread into a full-blown amusement park with all the requisite rides and attractions: the Texas Tornado double loop and two other steel coasters as well as a trio of water rides to satisfy the thrill-seekers; tried-and-true standards like bumper cars and a Tilt-A-Whirl; a Midway-style arcade with games of chance and video games; and a kiddie area with a merry-go-round, a miniature train, and cars, boats, and planes that go round and round. Wonderland Park, 2601 Dumas Drive, Thompson Memorial Park (off U.S. 287), Amarillo (806-383-3344, 800-383-4712; wonderlandpark.com). Call for hours; $1.50 to $3 per ride (unlimited passes for most rides $9.95 weeknights, $15.95 weekends). J. N. P.

DOWNTOWN

Hico (pronounced “High-Co”) has a vibrant downtown historic district that’s charmingly free of overcommercialization. Locals still shop at the hardware store and buy jeans at the clothing store, but there’s also plenty for visitors to see and do on the main drag, Pecan Street. The string of limestone buildings, built in the Western territorial style, replaced wooden structures that burned down in 1890.

When the railroad was active, Hico had six hotels, an opera house, a mercantile store, cotton gins, and blacksmith shops. Now most of the downtown businesses deal in rustic antiques and “ranch-style” merchandise. But there’s still a working blacksmith, John Frederick. He turns out mostly ornamental and decorative ironwork like candleholders that he and his wife, Polly, sell in their store, Frederick’s of Hico. Drop by and you’ll likely find him in his workshop at the back of the store, hand-forging his creations on an anvil.

A small museum on Pecan explores whether Ollie L. “Brushy Bill” Roberts, who lived out his final days in Hico and died in 1950, was really the outlaw Billy the Kid, as he claimed. According to a marker near Brushy Bill’s statue a couple of blocks away, Hico residents believed his story “and pray to God for the forgiveness he solemnly asked for.” Hico, intersection of U.S. 281 and Texas Highway 220 (800-361-4426; hico-tx.com). K. J.

CHURCH

From the outside, St. Paul Lutheran is deceptively simple. Built in 1871, with a tall bell tower and thirty-inch-thick sandstone walls covered with white plaster, it rises high above the surrounding green fields in Serbin, a tiny rural community near Giddings that isn’t even on many Texas maps. The unadorned exterior makes the inside even more stunning. The wood-plank ceiling is painted sky blue and hand-stenciled with decorative borders. The chandeliers are the original kerosene lamps converted to electricity. The plain wooden pews and baptismal font are also original, and the huge pipe organ dates to 1904. Unlike most modern churches, St. Paul has two stories with an unusual wraparound balcony and a balcony-level pulpit, where the Reverend Michael Buchhorn preaches his traditional Lutheran service using the old liturgy. At Christmas, Easter, and other major religious festivals, services are held in German as well as English. The church draws members from miles around and boasts a congregation of six hundred people. Many are descendants of the original founders, a group of Slavs called Wends who immigrated to Texas from Saxony and Prussia in the 1850’s. “These are people who value staying together, staying close,” Buchhorn says. “It makes this a special place.” St. Paul Lutheran Church, 1572 County Road 211 (off FM 2239), Serbin (979-366-9650). K. J.