When my father was told he was going to die soon, he declared he would not die in our house. It was the home where he and my mother had raised my brother and sister and me. “This has been a happy place,” he told us. “Your mother will probably live the rest of her life here. If I die here, then every time you go into the room where it happened, that’s what you’ll think about.” He made plans to move to Corpus Christi to a house my mother had recently inherited, and he and my mother walked out of their home together, knowing that she would come back and he wouldn’t.

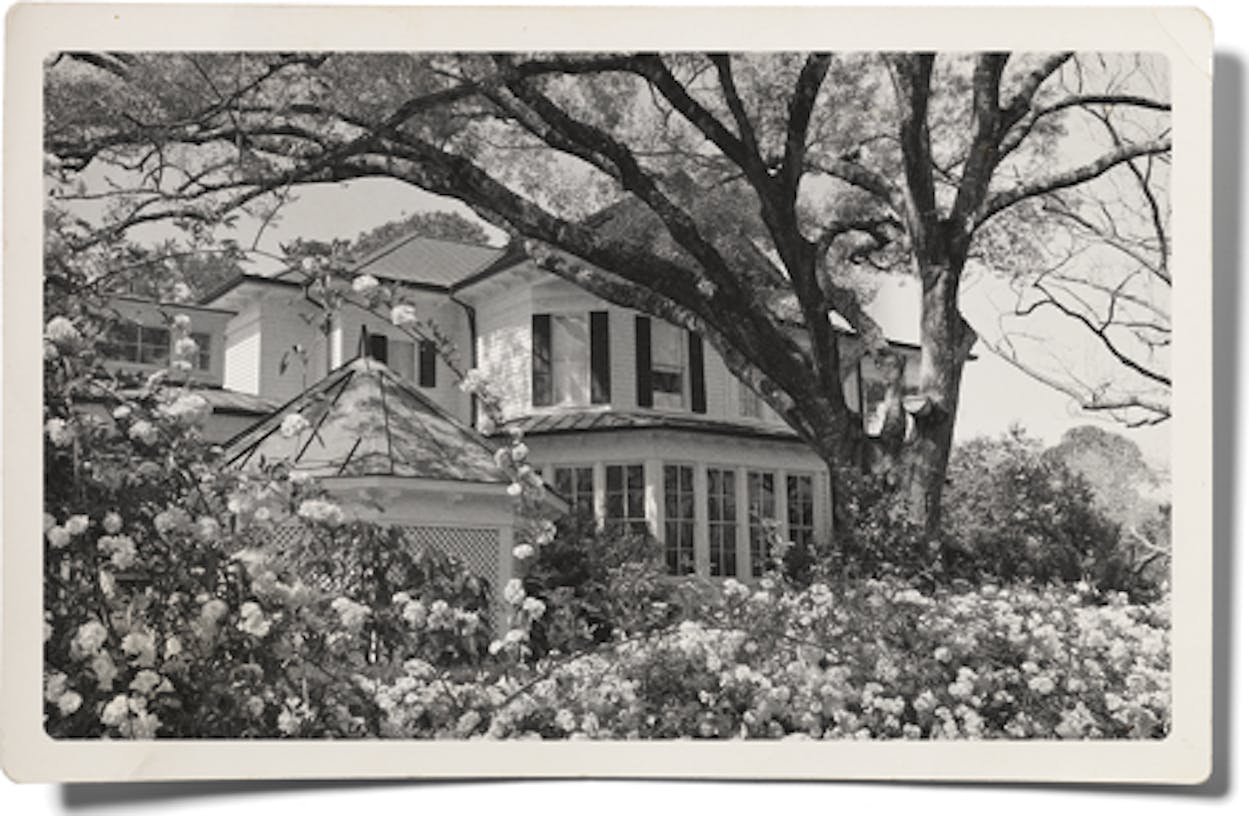

The first time they had seen our house was in 1961, when I was two years old. My father had resigned as minister of the First Baptist Church in Nacogdoches to run for Congress on a civil rights agenda, and lost, and accepted the job of president of San Marcos Baptist Academy. He scouted out the house and took my mother to see it, a huge old structure that inhabits almost a whole block in the historic district of San Marcos, just down the hill from Wonder Cave. She sat in the car looking at it. “What do you think?” he asked her.

The exterior architecture was perfect Greek Revival copied from a house on Peachtree Street in Atlanta, but the interior was a Victorian horror. The rooms were dreary, the woodwork coated in dark-red varnish, the walls covered with garish wallpapers.

“Who would wash all the windows?” she wanted to know.

It’s a testament to my father’s infectious enthusiasm, his foresight, and general bullheadedness that they bought the house. It needed to be re-plumbed, re-wired, re-floored, and re-roofed. For a year I toddled along behind the work crews, inhaling fumes of varnish remover and playing in lead paint sanded off the exterior. The paint was so thick on the ground it looked like snow, and I have always wondered if my slow reading and poor math skills are because of this remodel. We moved into the house when I was three and my brother was six; my parents named it Crookwood, because the previous owners were the Woods. My sister was born a year later, and was brought home and laid on the blue vinyl window seat cushion that my brother and I called the “mile a minute” because we used it to sled down the stairs. I lived there for all of my childhood except for two years away, when my father was in the Lyndon B. Johnson administration. Now when I think of my hometown, it’s the home, more than the town, that comes to mind.

The house, and the yard too, have changed over the years. What was an open stretch of grass in the back now has hedgerows and patios, a flower garden, a fishpond blessed by a mossy old statue of Saint Francis feeding the birds. The pond sometimes has fish and sometimes doesn’t, depending on whether raccoons have raided. An area where my dad buried our dogs is marked with a stone: “Our Faithful Dogs.” Pecan and oak trees have grown taller and wider. My father wasn’t a gardener, but he loved to cook up plans and stroll around, chewing on his cigar and overseeing the progress. It took him nearly thirty years to talk Mrs. Denny next door into selling part of her lot so he could attach it to ours. He turned it into a garden of native shrubs and trees with a marker reading “Garden of the Grandchildren” as a monument, by then, to his.

By far the most alluring structure of the property, for children, was an old carriage house we called “the barn.” It had horse stalls and feed storage rooms and a hayloft upstairs with chutes down to the stalls and two large plank windows we could shove open to look out over the yard. There was a grain bin with doors that opened like laundry hampers. It was unattached from the wall, and once, when my sister and cousin and I climbed into the compartments and poked our heads out simultaneously, the shift in weight toppled the whole piece over and we were nearly decapitated. We pulled our heads in like turtles before the doors hit the ground.

Our neighborhood had more boys than girls, and the barn was their main hideout. I was a tagalong, and in order not to include me officially in their club they dubbed me a “mascot” and made up ways to keep me out of their hair. They left me once in a feed storage room hiding from “Indians” they said would scalp me, and then forgot I was there. The tin walls had been painted with skulls and crossbones by someone years before, and I was scared of these but terrified of alerting the Indians if I yelled for help. I can still conjure up the silence, the dusty smell of that place, the exact shape of the painted skulls.

Later we kept some animals in the barn. I had a goat named Bilbo Baggins that lived in a pen at the back until he developed a taste for the poisonous oleander leaves. After rushing him to the vet a couple times to have his stomach pumped, we drove him out to my grandparents’ property near Kerrville. When he was gone, the barn seemed empty, so we got a pony named Banjo. But he turned crazy and mean, as horses will do when isolated from other horses, and chased me around the yard one day trying to trample me. We turned him loose at the Laity Lodge Youth Camp that my grandparents owned on the Frio River, and he lived the rest of his life wandering with a band of other retired, ornery horses.

Next my father decided we should raise chickens. He acquired a couple of nesting hens through a friend named Pete Owen, and we awoke one morning to the magic of eight little chicks running around the stalls. I claimed the only brown one and named him Lancelot. We petted and loved the chicks, but as they grew they became aggressive, and Pete Owen confessed he had gotten the hens from a man who raised fighting cocks. My parents were puzzling over how to get rid of them when our silky terrier, Hobie, pushed through the gate behind my sister and me one day and killed them all. We chased after him with sticks, screaming, but he was faster than we were. We had nightmares about that slaughter for years.

My dad’s next project was the construction of a swimming pool beside the barn, under a huge Spanish oak tree. We perched in the limbs of the oak as the hole was being dug, looking down at the excavation, the smell of raw dirt giving us the sense of uncovering a new world. Our old blind Boston terrier, Mrs. Micawber, fell into the hole sometimes when she was making her usual rounds, and had to be gotten out. After the bottom was cemented, the fire department brought a truck over to fill the pool with water. Neighborhood kids came, and we ran in circles inside the pool while the water tumbled out of a yellow hose and got higher and higher. Finally we were swimming.

My mother was worried about the risk to my sister and Mrs. Micawber, so she installed a device that set off a buzzer up at the house whenever an object fell into the pool. But it went off with every leaf and acorn that dropped out of the oak tree, and we became nervous wrecks, running out to the pool numerous times a day expecting to find my sister or Mrs. Micawber sunk to the bottom. Finally my mother unplugged the device and put in a wrought-iron fence with a gate between the house and the pool.

When my sister was slightly older, she almost did drown one time. She wedged herself, underwater, between the ladder steps and the side of the pool, the glass of her swimming mask pressed against the cement. I heard her screaming from underwater and saw bubbles coming up, and since no one else was out there, I ran from the far side to pull her out. When I saw how stuck she was, I tried to push her down and under, but she thought I was trying to drown her and clung to the arms of the ladder, screaming in bubbling bursts. Finally I shoved her hard enough and dragged her up on the right side, her bony chest skinned and bleeding. Since then, I’ve often reminded her that she owes me her life.

In summers, there were days when we woke up in the cotton gowns we called “nighties” and ran straight to the pool, swam all day in our nighties, dried in the sun, slept in the same nighties. We left little bloody toe prints up to the house from the abrasive cement of the pool rubbing the skin off.

My parents later remodeled the barn into an office and guesthouse. When I was twelve years old, the movie director Sam Peckinpah stayed there with his British girlfriend, Joie, while he was filming The Getaway. Initially Steve McQueen was supposed to be our guest. There weren’t a lot of hotels in San Marcos, and the scouting crew had approached my parents with the request. But then my mother was told that McQueen was in a relationship with his co-star Ali MacGraw, who was married to someone else, and she thought this would be a bad example for us to see. So we ended up with Peckinpah. My mother was led to believe he was married to Joie, but he wasn’t.

McQueen came over a couple of times and was friendly to us, warning my brother to stay away from drugs. Peckinpah, by contrast, was irritable and had a drinking problem. He wore a bandanna around his head, and reflective sunglasses, and my sister and I were scared of him. He threw knives at the walls in the barn and brought in a king-size bed. My parents invited him and Joie up to the house for meals a few times. They came for our family Sunday lunch of roast beef and mashed potatoes and peas. He told us our barn was haunted. He said he had seen the ghost. He also asked if any of us would like to be in the movie.

He and his retinue helped themselves to our pool. We liked Joie, who was young and pretty and always gracious. My sister and I ventured out to the pool once while Joie was doing pull-ups on the diving board, and noticed that she had hair growing under her arms. We had never seen hair like this on a woman and didn’t know hair even grew there.

In the movie, my mother and sister and I walked into the bank shortly before the robbers burst in and ordered everyone to get down on the floor. This was scarier than we anticipated. “Keep your heads down!” they shouted at us, through take after take, pointing their guns. My sister was seven years old and kept lifting hers. “CUT,” Peckinpah said. “CUT.” One of the robbers once pulled off his ski mask to wink at me reassuringly, but Peckinpah kept us on edge. During one take, my mother, grabbing my sister to drag her down to the floor, knocked over an ashtray filled with sand and cigarette butts. Peckinpah lost his temper. “CUT!” he shouted. “AGAIN!” My sister lifted her head from the floor and giggled nervously. “Lift it again,” Peckinpah told her, “and I’ll barbecue your dog.”

He meant this to be a joke, but my sister believed him. We kept the dogs on leashes after that.

Shortly after Peckinpah vacated our barn, we learned that he had married Joie in Mexico while filming the end of The Getaway in El Paso. I saw the movie on VHS for the first time decades later and freeze-framed my two seconds on-screen. There I was, in polyester bell-bottoms, clutching my mother, reaching for my sister, throwing my hands up over my ears.

But it was the house and not the barn where our lives were centered. My mother didn’t believe in making even the formal rooms off-limits, so we had free run of the place. A Chippendale table in the front hall got its leg knocked off so many times by children running past that my mom didn’t bother to fix it until after we were grown. She just kept propping it back up.

My first bedroom was near my parents’ and overlooked the front porch. Later my sister moved in with me. It was noisy in there: Trains on the track not far away blew their horns all night long, dogs down the street barked, pigeons strutting in the tops of columns on the porch cooed loudly in the mornings. A pair of barn owls nested in the roof eaves, beating their squealing prey to death beside our windows.

At some point when I was in middle school, my parents allowed me to move to the “guest” room across the hall, next to my brother’s room. My brother’s loud music came through the air vent, so I fell asleep to the wailing sirens of Bloodrock’s “D.O.A.” One of the windows in this second bedroom opened onto the roof over the dining room; I often climbed out and sunbathed on the asbestos shingles. A time or two I climbed to the very top of the highest chimney and saw the whole town. By the time I was in high school, I had a boyfriend down the street and started sneaking out the window at night to go see him.

Just outside the door of my bedroom, a wide stairwell led down to the front hall. We called these stairs the “red stairs” because the carpet was red, as opposed to the “blue stairs” down to the kitchen. Both stairways now have neutral carpet, but the names have stuck. It was the red stairs I crawled up the only night of my life I was ever too drunk to walk straight. After losing both of my contact lenses vomiting in the front yard, I stumbled inside and dragged myself up the red stairs and into my parents’ room, where I crawled to my dad’s side of the bed to ask him if he would help me get into my bed.

Many years later, when my first marriage was coming apart, my father came to New Braunfels to help me move out of my house and haul my belongings back to San Marcos for temporary storage. The day happened to coincide with a tour of Crookwood by the heritage association. My father and I hauled load after load of boxes and bedding and a large mattress through crowds of tourists, up the blue stairs, through the hall and up to the attic. I was humiliated and deeply depressed, but Dad just barked at the docents in an authoritative voice. “Excuse us, please. We’re coming through,” he told them. When we got to the attic with the mattress, I didn’t want to go down again. “Neither do I,” my dad said. We sat on the edge of the mattress, staring at a bank of windows and waiting the time out. I thought of how I had climbed out those windows as a child and tramped around on the flat, pebbled roof over the front porch. How I had dared myself to the edge. How my father on Christmas Eves used to go out there with jingle bells and stomp around so we would think we’d heard Santa Claus and his reindeer. I thought of how my brother once got in serious trouble for dropping water balloons from that roof on trick-or-treaters, and how my life had horribly come down to hiding out in the attic of my childhood home. And suddenly it seemed funny. I started laughing, and after a while my dad and I were hooting like children.

There were drawbacks to living in our house. For one thing, it seemed to me a little pretentious to live in a house with a name. It was one of the biggest houses in town, and I felt apologetic about that. And there were flea problems, rat problems. Raccoons in the roof, dead squirrels in the walls. Strangers had their wedding photos taken in our front yard. There was never a chance to be alone—people were always around. Dogs were underfoot; our female silky, Adelaide—given to us by President Johnson when we had moved to Australia—enjoyed mating with Hobie in front of all our friends. We needed to have her spayed, but Dad vetoed the plan. “He loves her so much,” he said, and talked the vet into giving Hobie a vasectomy instead.

But at every painful juncture in my life, I have headed for that house. Divorce, miscarriages—every failure—I have packed up and gone home. When I traveled with my boyfriend—now my husband—to India and found myself on Christmas Eve in the holy Hindu city of Rishikesh, I was so woefully homesick I hired an open rickshaw to haul me outside town in freezing weather to buy a bottle of Bonking Whisky. I stood two hours in line the next day drinking the whiskey and waiting to call home.

My father’s final project on the house involved transforming the outdoor patio off the kitchen, where my sister and I had held our wedding receptions, into what he called the Orangerie, after the art museum in the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris. It was finished shortly before his death, and he sat in that huge, glass room, surrounded by potted orange trees, listening to opera at full volume for weeks before he moved to the house in Corpus Christi. “If I get to a point where I’m not lucid,” he told us when he was settled in Corpus, “and I ask to go home, don’t take me.”

The hardest part was that he did ask, a few days before his death. He was not lucid, but he knew enough to know he was not where he wanted to be. But we stuck to our promise. We didn’t take him. He died in Corpus Christi.

I have had a relationship with that house, on its sloping acre of the Balcones fault line, now for nearly half a century. I took my husband there on our first date and later married him there. I was introduced to Lyndon Johnson in the dining room when I was five, and as an adult attended dinner parties in that same dining room with James Michener, Lady Bird Johnson, and a host of other powerful and fascinating people.

But it’s the smaller memories that confront me at unexpected moments. If I open a certain closet, I remember a tiny mummified kitten, still in its birth sac, left there in one of my shoes by the mother cat and undiscovered by us for nearly a year. If I open a different closet, I see scribblings where my parents backed us up to the door frame and marked our heights as we grew. In the closet of my second bedroom are blue footprints from the time I dipped my feet in paint and walked them up the wall by holding on to the clothes rod. They become paler, and more smudged, the higher they go.

I now watch my children and nieces and nephews empty their Christmas stockings on the same stairs where my brother and sister and I emptied ours. There’s talk sometimes that some of us, during these family gatherings, might like to branch out into hotel rooms, but none of us ever has. We overflow to the barn, to the bed Sam Peckinpah left us. We inflate air mattresses in the study. Sometimes there’s mild disgruntlement about who should get which rooms, but never enough for any of us to clear out. The farthest we ever go is to the room beyond the garage. We call it “Esperanza’s room,” in spite of the fact that Esperanza, our beloved nanny and cook, hasn’t lived there in 25 years.

But all of us know that nothing can last forever. Last summer my mother sent an e-mail to my brother and sister and me. She was grief-stricken. The giant Spanish oak tree over the pool, which we had climbed in, and played under, throughout our childhoods and which still seemed to be thriving, had crashed to the ground that morning. An arborist was bringing in experts—he had never seen anything like it. “Every branch and leaf healthy,” my mother wrote, “shining, and the crater where huge roots should be virtually empty. There’s an allegory in there somewhere, but not one I want to think about this morning.”

She sent pictures of the broken trunk, its massive spread of limbs submerged in the swimming pool and crushing the roof of the barn. The removal took weeks; repair of the pool and the barn went on for months. The local newspaper featured a photo of bulldozers dragging parts of the tree away. “Come see it before it’s gone,” my mother told us.

But I didn’t want to go see it. The strange and sudden death of the tree had brought to our house that taint of mortality that my father, through his act of will, had forestalled thirteen years ago. Nature was proving its point. Eventually it would have its way. And for the first time in my life, I didn’t care to go home.