The abiding image of America is not the farming aristocracy of Thomas Jefferson or the bustling hubbub of today’s cities. It is the small town, where birth flows into death amid the steady rejuvenation of generation passing into generation, where, as Lyndon Johnson used to say, “they know when you’re sick and care when you die.” Texas is urban now, the third most populous state in the nation, with three of the ten largest cities. This urban growth, however, has come almost entirely since World War II. It has come so quickly that most of us, even if we live in those cities, remember a different Texas, the Texas of the small towns, the thousands of country centers that drew like a magnet from the surrounding farms just as the cities would soon draw from the towns. The small town was everything, all our virtues, all our memories, the backbone of America. In our cities we tend to idealize it, to make the small town more than it was, to forget its narrowness and its limitations; we remember only that convivial flavor of the courthouse square on a Saturday, when everyone came to town.

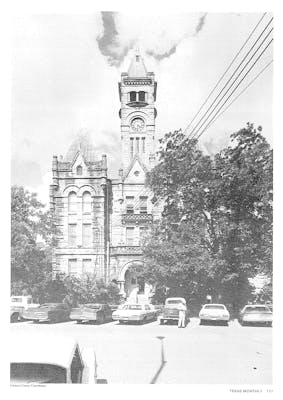

Even in the Texas of Houston, Dallas, and San Antonio, that small town remains, and people still come to the courthouse square on Saturdays. We chose Hallettsville as our typical small town, although we soon discovered that it was typical only to outsiders. To the people who live in Hallettsville, there is no place like it. The town is on U.S. 90-A, midway between Houston and San Antonio. Founded in 1836, the year of Texas Independence, Hallettsville was named for Mrs. John Hallett, who gave the land on which it stands. The town has a distinct Bohemian flavor but also draws from German, Anglo, and black traditions. Around Hallettsville the countryside is lush rolling farmland with fields of maize and grazing cattle. The Lavaca County Courthouse, a magnificent Romanesque structure, sits on a hill in the middle of the town square. On a clear day, the metal spire on top of its central tower reflects the sunlight like a beacon guiding a traveler toward town.

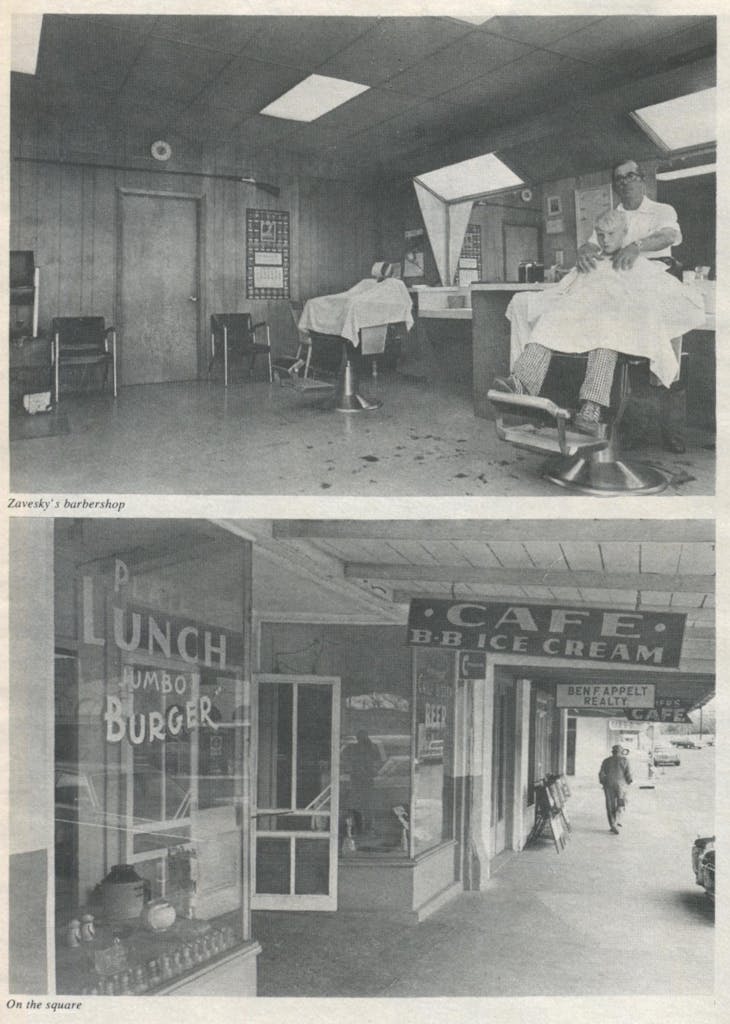

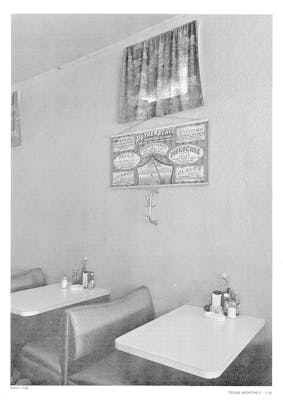

On the square’s northeast corner are two cafes, Rehak’s and Rother’s. Either is a good bet for a fine cup of coffee and a real homemade hamburger. Step inside and McDonald’s will seem thousands of miles away and 50 years in the future.

The town motto of Hallettsville is a quote from William Jennings Bryan: “Destroy our farms and grass will grow on the streets of our city.” In Hallettsville, at least, farms are still alive, if with a little government help. On any Saturday morning, particularly if the weather is pleasant, the courthouse square comes alive with farmers coming in to market. George Bucek, who’s been a merchant in Hallettsville all his life, tells how Hallettsville’s economy works: “In this town we got poor, damn poor, rich, and damn rich. And we need ’em all. You can’t pick a pecan with a machine. The poor man and his family goes to pick ’em. And you get a family of four pickin’ at thirty, maybe forty cents a pound, gettin’ half, and they got money to spend. You can feel it all over the square. Besides, if it’s the first Saturday of the month, they got their blue checks, the social security and welfare. Some folks say we spend too much in this country on welfare, and I agree. But you gotta help the poor man as long as he’s helpin’ himself. When you got no pecan crop, the small town can’t live without blue checks.”

Just a block east of the square is Vic’s Tavern. Vic’s place is a classic Texas domino parlor and a worthy host each year to the State Championship Domino Tournament, Every regular customer has his own special spot, informally reserved, and a stranger who enters is looked over from head to toe: is he a visiting hustler, or only a lost and woefully ignorant city slicker?

Just a block east of the square is Vic’s Tavern. Vic’s place is a classic Texas domino parlor and a worthy host each year to the State Championship Domino Tournament, Every regular customer has his own special spot, informally reserved, and a stranger who enters is looked over from head to toe: is he a visiting hustler, or only a lost and woefully ignorant city slicker?

In addition to the domino championship, Hallettsville hosts the State Championship High School Rodeo and the State Championship Fiddler’s Contest. These events are the source of considerable local pride. They happen in Hallettsville because people have worked to make them happen there. It is also a source of pride that the population of the town, after many years of slow decline, has begun to grow. The 1960 Census placed the population at 2808. The 1970 figure was 2712. Now Hallettsville has well in excess of 3000 residents. That’s not exactly booming, but the decline—so typical of America’s small towns—has clearly been reversed.

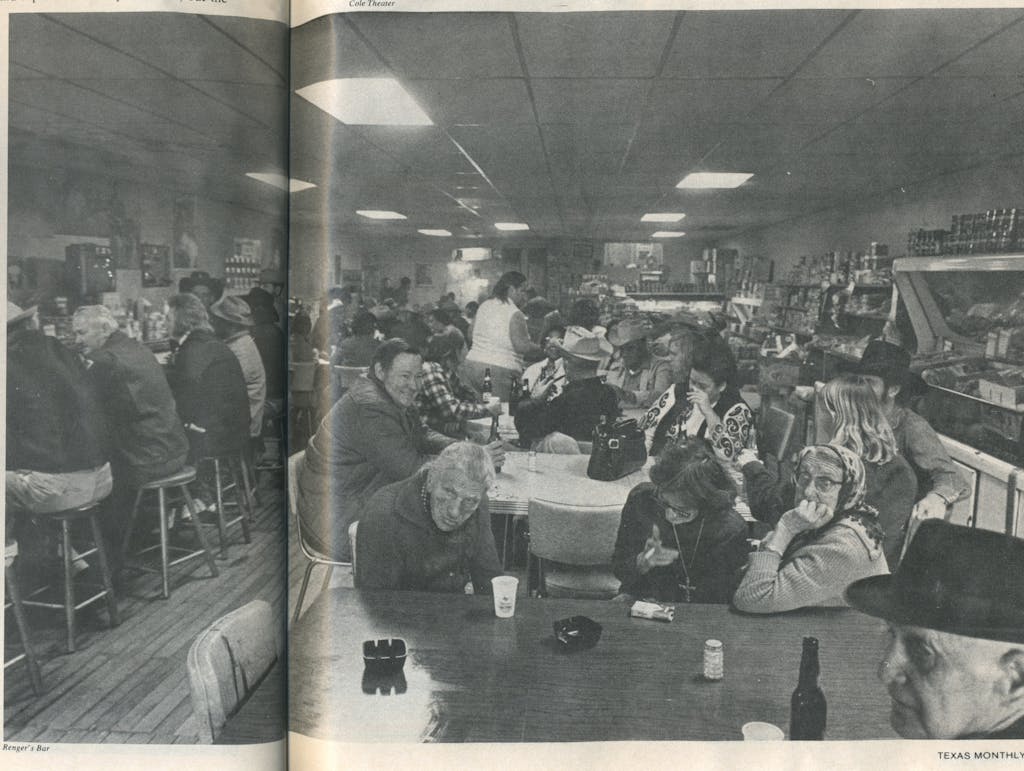

Bill Renger’s Bar on the northwest corner of the square is where to find a beer and a good time. Renger’s is a combination grocery store, meat market, bar, pool hall, and gathering place for people of all ages, black and white alike. If Hallettsville has a social center, Renger’s is certainly it. Bill himself is in charge, alternately slicing meat, serving beer, and sitting down at the tables for a little socializing himself.

On a sunny day, merchants around the square set out overalls, boots, potted plants, wing tip shoes, and a vast array of other items in front of their stores. Over at the Enco station, C. R. Hrncir will charge your battery, give you a wash job, or sell you a jar of his own special arthritis remedy, “Icee-Hot.”

Hallettsville’s movie theater, the Cole, sits on the north side of the square, offering the best of already-run-in-Houston movies. The management discovered years ago that what drew people to a local movie was whether they’d seen it advertised in Houston. So the Cole books any movie that has shown in the big city, even those with an R rating. There are classics, of course, movies which come again and again, never failing to draw the crowds. The two all-time favorites are Gone with the Wind and Blazing Saddles.

There are two barbershops on the square, but only Charles Zavesky’s offers guns as well as a haircut. The gun sales and repairs are strictly a sideline, but the shop is worth a visit just to see the proprietor’s personal collection, which is on permanent display.

Local people will nod and speak to you on the street, and it’s not that they think they know you from somewhere. It’s an example of simple courtesy, and the amazing thing for a city dweller is how well it works, how contagious it Is. You’ll find yourself blurting out a robust “Howdy!” to perfect strangers. The only problem is trying to pronounce proper names. Some of the Czech surnames look like the last line of an eye chart. Names like Hlavac and Hrncir are best left unspoken by the newcomer.

Copies of Hallettsville’s newspaper, the Herald Tribune, are normally for sale on the square. The paper is not so strong on world or national news, but it’s the only way to stay abreast of local events. Take, for example, this item in the Town Chatter column carried in a recent edition:

ERWIN HOLY relates an incident to us concerning BOB PESEK that continues to hold some mystery; ERWIN tells us on the cold, very windy day recently BOB PESEK’S hat was blown off his head and it rolled down the National Bank street to the south; this is not unusual, ERWIN says, for a man’s hat to be blown off his head, but PESEK chased the hat and could never find it; to this day the hat has never been found, HOLY said.

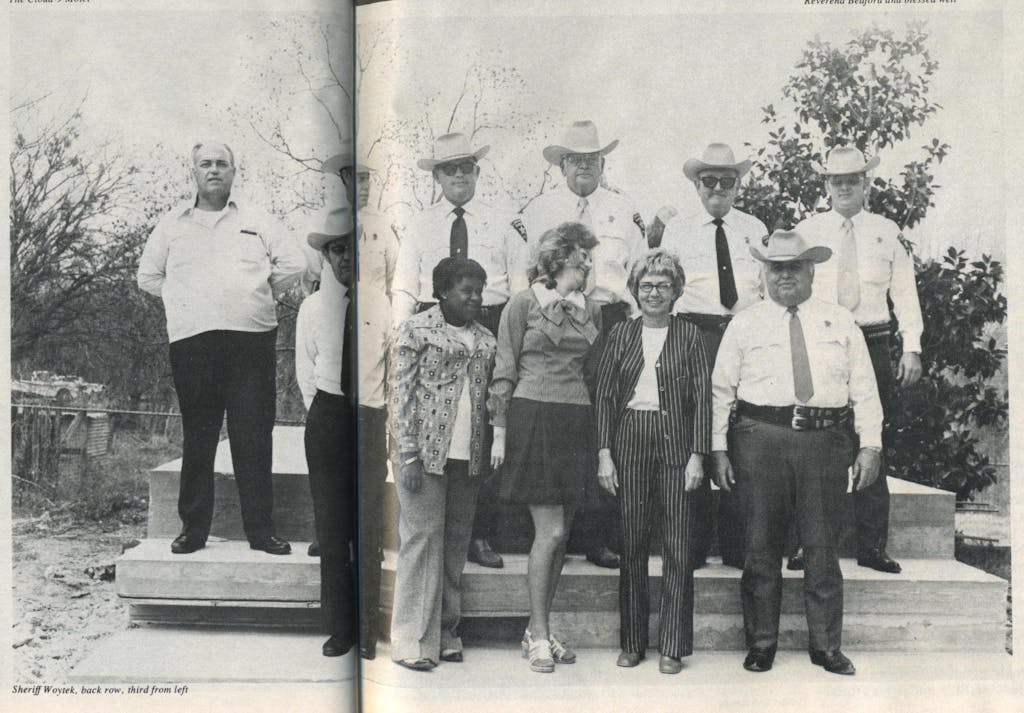

Some of the blessings of life in a small town are well known. For one, there’s less violent crime than in the big cities, and local law enforcement agencies tend to be relatively unencumbered by bureaucratic red tape. Sheriff Hilmer Woytek is from Sublime, a small community just east of Hallettsville; the word around Lavaca County is: don’t mess around with a man from Sublime. Lack of patience has proven to be a character trait indigenous to the region.

Citizens are provided detailed accounts of the activities of the Sheriffs Department in the local newspaper in Sheriff Hilmer Woytek’s Report. For example:

Thursday, February 19 Deputy attending to prisoners. Sheriff attending Hallettsville Chamber of Commerce meeting.

Deputy posting notices on bulletin board.

Deputies assisting Fayette County officers in looking for two subjects involved in armed robbery; subjects apprehended in San Antonio.

Sheriff on phone with subject on business matter.

Deputy in office serving capias and collecting fine in DWI case.

Sheriff on phone with District Attorney on business matters.

Deputy investigating report from subject reference some stray dogs trying to kill his sheep on FM 530.

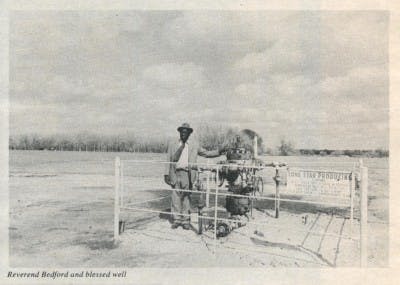

Other local blessings might come as a surprise. Reverend Morris Bedford, pastor of Good Hope Baptist Church, has lately extended his fold to include some of Hallettsville’s most prominent citizens, who are convinced that his blessing, properly and ceremoniously bestowed upon their oil and gas wells, virtually guarantees a gusher. Word of the Reverend’s percentage of return on blessed investments has traveled swiftly about town, but then all word seems to travel swiftly about town when the town is the size of Hallettsville. When Chuck Wedgeworth moved to town from Houston and innocently bought the other motel, the Bel Air . . . well, people noticed. Some of the more imaginative local gossips even suggested that organized crime might have found its way to Hallettsville.

The family of Sam Devall, or Colonel Sam Devall, as he prefers, has lived in Hallettsville for the past three generations; he “learned to walk toddlin’ through the courthouse,” The Colonel served in three wars and was discharged as a “full colonel of armor in the Army of the United States.” He then returned to Hallettsville, where he has been city attorney, county attorney, postmaster, and a member of the Texas Legislature. In the Legislature, the Colonel, as most anyone in Hallettsville can tell you, introduced a bill that made the present Texas flag the official state flag. As if these accomplishments weren’t enough, the Colonel is an Admiral in the Texas Navy and an Honorary Texas Ranger.

Colonel Devall waxes most eloquent when he talks about the brave soldiers, and in particular the generals, which Hallettsville produced in the Civil War. Yet he is quick to remind you that the people of his town are peace-loving folks, very thoughtful, and rather like a big family, especially in times of need. When asked if there was anything unique about the town, the Colonel thought for several moments, then replied: “In nineteen and thirteen, when ol’ Ripley started his column, he wrote ‘Believe It or Not, Hallettsville, Texas, has thirteen letters in its name, has thirteen saloons, has thirteen churches, has thirteen newspapers, and thirteen hundred population.’ And I never heard anything like that before.”

In the back of Mikulenka’s Store, nestled in his office between files and stacks of invoices will likely be George Bucek and his dog Omar. George used to own and operate Mikulenka’s, a dry-goods store that has been in business in Hallettsville since 1929. The store was started by George’s father-in-law, and George himself joined the business in 1940 when a flood wiped out his own grocery business. In 1972, George’s son Laddie returned from Viet Nam and borrowed money from the bank to buy his parents out. Now George keeps the books for Laddie and serves as credit manager. No credit cards are accepted at Mikulenka’s. George says the profit margin is too small to allow for the percentage taken by the card companies. Instead, Mikulenka’s encourages open charge accounts. When people apply for an account, George interviews them personally, tries to find out “who’s hustlin’, who’s settin’, and who’s muddlin’.” There are very few bad debts incurred at Mikulenka’s. If somebody gets stow on their account—which means 90 days behind—George will call them in and “advise them to stay at home more and get a bigger garden.”

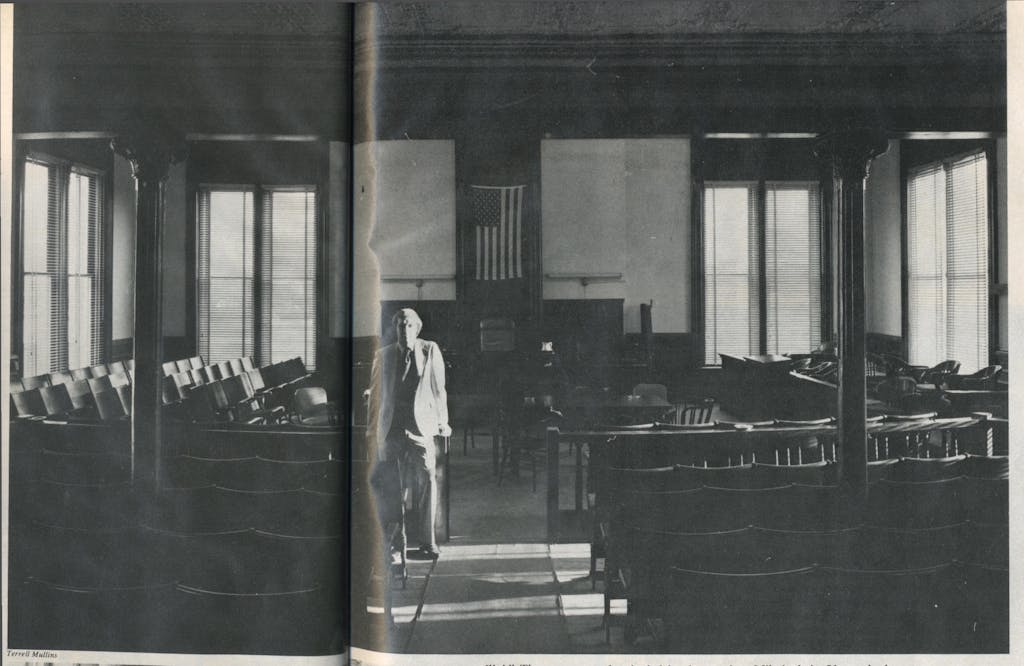

An elevator was installed in the courthouse several years ago, but most of the older Bohemian citizens clearly prefer the physical rigors of two flights of stairs to the hazards of mechanical levitation. Upstairs is Terrell Mullins, 30, county attorney for three and a half years now. Terrell’s father, Claude Mullins, was superintendent of schools in Hallettsville for many years and later served as county judge. Terrell spent two summers clerking for a Houston law firm while he attended the University of Texas Law School and could easily have prospered in the city. But when he received his law degree, he decided to return to Hallettsville. Why? “Because,” he says, “of the way you can deal with people here. It can be more personal. The volume of work required of a lawyer in a big city firm makes it virtually impossible to deal with people personally.”

As county attorney, Terrell’s responsibilities include trying such charges as driving while intoxicated. There are a very large number of DWIs in Lavaca County, sometimes a dozen or more each weekend. One of the obvious difficulties of prosecuting these cases in a small town is that Terrell is dealing with acquaintances, not to mention friends, people he encounters and speaks to on the street every day. “You absolutely can’t let these things drop,” Terrell remarks. “If I let a fellow go, just dropped the charges because I know him and think he’s a good guy, then the next day or the next week, everybody would know. They’d all know because you can’t keep those things quiet in a small town. I treat everyone with the same rules. It’s really the only way I could ever operate.”

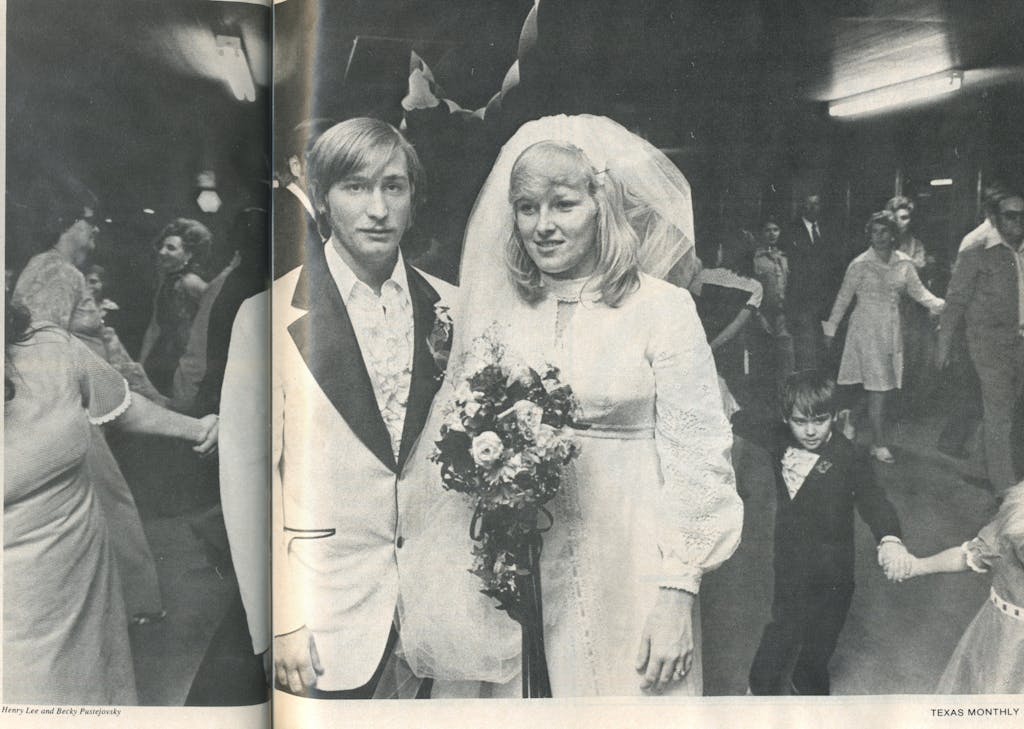

Many of the Czech and German customs which were once so much a part of life in Hallettsville have faded away. Laddie Bucek, for example, can vaguely remember a custom practiced by his grandparents which they called “butzen,” a gesture of gently bumping heads upon greeting. But he can’t remember just how or when it was done, or when it stopped. However, one very grand tradition survives: the Czech wedding. More than any other event, weddings are the focus of social life for people of all ages and all social classes.

In February, welder Charlie Reeves announced the intended marriage of his daughter Becky to young Henry Lee Pustejovsky. Invitations went out to 450 families for the wedding and reception dinner. As is customary, the public was invited for beer and dancing after dinner. The wedding was to be at one o’clock in the afternoon at the Sacred Heart Church. The reception was set for Blase’s Place, out west of town, a tiny beer tavern adjacent to an enormous dance hall.

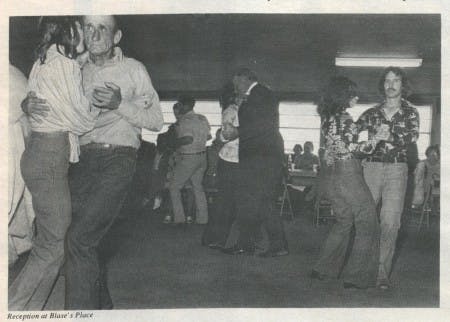

More than 850 guests attended the reception, or more than a fourth of the population of the town (and there were two other large weddings that day). Music was provided by the Rondells, a group from Yoakum. Early in the afternoon, 450 pounds of sausage and 250 chickens went on the grill. Nobody got a figure on the total volume of beer that was drunk, but the 200-gallon mark was passed about seven o’clock that evening, before the grand march began.

The grand march is the high point of the wedding, and everyone who can still get to their feet after an afternoon of drinking may take part. The march is led by an elder Bohemian couple who knows its complex movements. They begin in a stately fashion, leading two single-file lines, and wind around the hall. Lines merge, become couples marching together, then rows of couples, turning and twisting together in increasingly complex patterns. Stateliness yields to frolic as the music swells in volume and gains tempo. Five hundred people are following, more or less, an old Bohemian couple and a pair of giddy newlyweds. Somehow the entire procession forms concentric circles, turning in opposite directions around the bride and groom in the center of the hall. Then, the march music stops, and everyone watches as the newlyweds dance to the bride’s favorite tune. On this night, for Becky Pustejovsky, the Rondells broke into a fine rendition of Freddy Fender’s “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights.” Couples move onto the floor for dancing, beer flows, children play, and Charlie Reeves allows as how he’s pleased that Becky has chosen to marry a local boy.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Photo Essay