The attorney general gazed out across the Bosque River Valley, took a deep breath, and raised his Remington 12-gauge shotgun. “Okay,” he called out. “Can I see one?” An orange clay pigeon flashed across the sky before disappearing into a field some forty yards away. He turned and laughed: “Can I see one more?”

It was a bright-blue mid-May afternoon, and Greg Abbott was relaxing with some of his old classmates from Duncanville High School, Billy and Buzzy and Randy and Rickey and Kevin and Joe. If those names sound like they come from Ward Cleaver’s America, that’s because they do. Abbott had a classic small-town upbringing; these are the friends he stayed up late with playing cards and dominoes before drifting off to sleep on backyard trampolines. The men have remained close over the years, happily recalling the times when they first tried chewing tobacco on a football trip to Corsicana or pulled an all-nighter while puzzling over the periodic table. The property, a gorgeous piece of land between Glen Rose and Hico, belongs to Rickey. Each year they try to gather here to swap stories, catch up on their families, and do a little hunting and fishing.

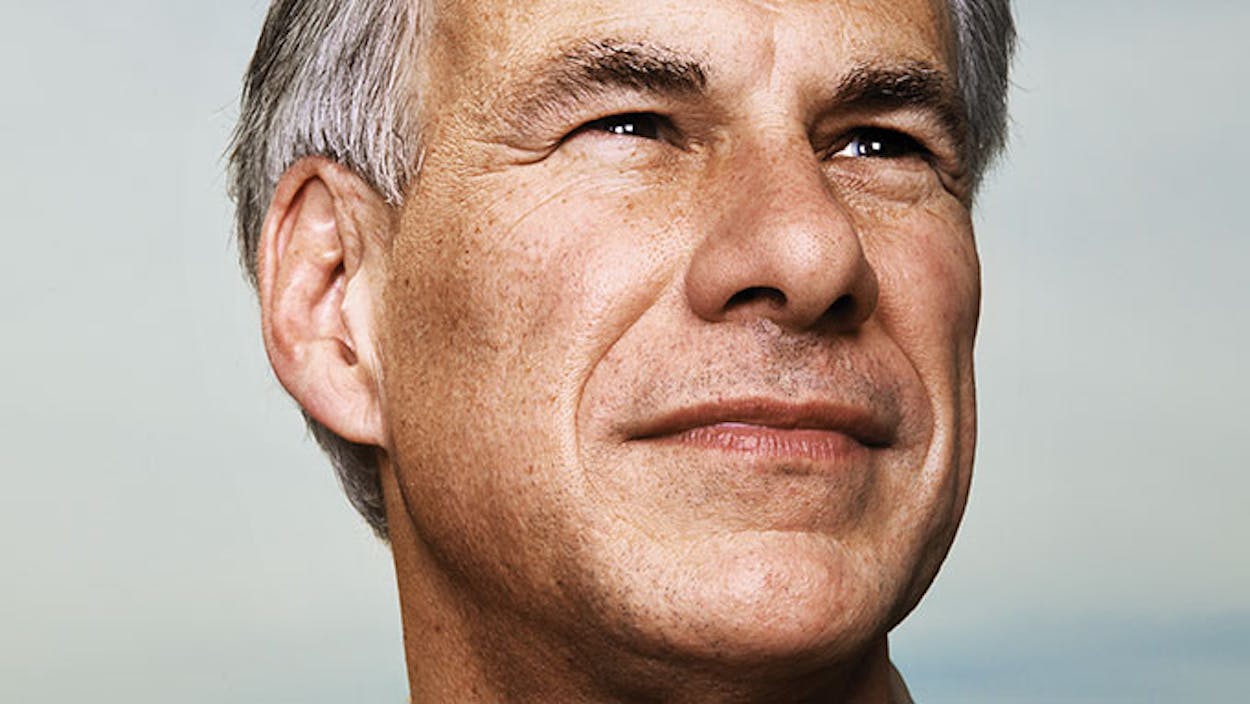

While one of the men adjusted the automatic trap, the 55-year-old sat in his wheelchair on a wide wooden deck and took in the view. He wore hunting boots, casual brown pants, and a gray short-sleeved shirt. “See that ridge over there?” he asked, pointing off into the distance. “Remember when we went out there and shot birds?”

“Well, shot at birds,” Rickey replied.

“That’s right,” Abbott said with a broad, easy smile. “A lot of birds went home happy that day.”

Soon the trap was ready, and the group grew silent. The attorney general raised his shotgun again. “Pull!” he cried.

The clay pigeon took flight at a more leisurely speed, and he squeezed the trigger. Boom! The pigeon sailed on, undisturbed. Boom! The target landed gracefully in the tall grass, fully intact. The group erupted with the kinds of jokes that high school buddies love to make at one another’s expense, even when one of them is the state’s highest-ranking law enforcement official. “Who gave Greg the box of blanks to shoot with?” Randy asked. Buzzy laughed. “This is where we do the Dick Cheney,” he said. “Better run!”

Abbott brushed them off and reloaded. “Pull!” This time, the moment the clay pigeon came into view, it exploded into a shower of orange bits. “Great shot, Greg!” went up the chorus.

He missed a couple, endured some more jeers, and hit a few more. After a while he called for someone to join him, and the games of knockout began. On his first round, he hit the pigeon, and as it came apart, he fired again and hit one of the larger fragments, an impressive shot. A few friends cycled through, then they switched games and fired at ten pigeons in a row to see who could shoot the most. Thirty minutes went by, then an hour, then an hour and a half. Abbott never stopped shooting. Once his friends had all had a chance, he called me over to shoot. I acquitted myself respectably. He then asked if the assistant to the photographer, who was there to take his picture for the magazine, wanted to give it a try. She agreed reluctantly, saying she hadn’t shot since she was a kid, but once she started, she never seemed to miss. From the back, Randy called out, “He’s the attorney general—you’re supposed to let him win.” But Abbott was having none of it. He offered her a wide smile and shook her hand. “That was terrific shooting,” he said.

The attorney general’s own shooting was, as a Boy Scout leader once told me at summer camp, “not too bad for the range, not so good if you’re under attack.” What was notable was his endurance. Everyone else took breaks; Abbott just kept blasting away. His shoulder, I caught myself thinking, is going to be black-and-blue tomorrow. Like many Texas politicians, Abbott has made guns central to his identity, but the intensity with which he does so seems at least in small part an attempt to balance out the fact that he is disabled.

No one can deny his toughness, which has come to define his career. A former track star at Duncanville High, he was nearly killed at the age of 26 during a freak accident while jogging. Ever since then, he has willed himself to extraordinary heights. A lawyer by training, he became a state district judge in the early nineties, then a member of the Texas Supreme Court, and finally the attorney general, in 2002. In all that time, he has never lost an election. Now he looks almost certain to continue that streak. He declared his campaign for governor in July, and while knife fights have broken out in several down-ballot races—the battle for lieutenant governor features a three-term incumbent fighting for his political life against three current officeholders—Abbott has escaped the prospect of a bitter Republican primary, drawing only a single, poorly funded opponent, former state party chair Tom Pauken. And by mid-September, no Democrat had yet declared for the race either. Despite the fact that a recent poll showed that 51 percent of Texas voters have no opinion of him, barring an unexpected twist, Greg Abbott will be the next governor of Texas.

That means he has already become the de facto leader of the state GOP, as Rick Perry, who will not run for reelection, rides off into the sunset. This transition comes at a critical time: the party is pushing further to the right on issues both social and economic at the same moment that sweeping demographic change and a faint heartbeat in the moribund Democratic party have made the long-term prospects for Republicans less clear. Though they control all levels of government in what is an inarguably conservative state, the pressure will be on Abbott to maintain that grip. If it loosens, he’ll get the blame.

Over the years Abbott has staked out positions that clearly define him as a conservative’s conservative. As he tells anyone who will listen, the attorney general has sued the Obama administration no fewer than 27 times. Earlier this year he described his typical workday as “I go into the office in the morning, I sue Barack Obama, and then I go home.” Or, as he puts it on the campaign trail, “I didn’t invent the phrase ‘Don’t mess with Texas,’ but I have applied it more than anybody else ever has.” He has successfully defended the placement of a Ten Commandments monument on the Capitol grounds before the U.S. Supreme Court and has threatened to file suit against the City of San Antonio for passing an ordinance in September that prohibits discrimination against people because of their sexual orientation. He has filed a brief with the Supreme Court arguing that the Second Amendment provides citizens with an individual right to bear arms. And he has gleefully battled perceived federal overreach in matters of environmental regulation, redistricting, and voter ID.

At the same time, he has tried to use his biography to soften those partisan edges. The pitch is simple: Because of his disability, he has a special understanding of the challenges facing all Texans—and the fact that he has accomplished so much is an indication that they can achieve great things too. Because his wife of more than three decades, Cecilia, is a third-generation Mexican American woman whose grandparents didn’t speak English, his family embodies the blending of cultures that is key to the future of Texas.

But does Abbott have what it takes to broaden the Texas GOP’s base and ensure its continued dominance? His daunting war chest of approximately $22 million provides ample evidence that many politically active people across the state think the answer is yes (Pauken, by comparison, has raised less than $250,000). Abbott’s fundraising totals, combined with a careful sequence of chess moves, have allowed him to capture the feeling that all politicians running for office desperately crave: inevitability. As the deliberate rollout of his campaign this summer made clear, he is both smart and cautious. “You know that scene in The Bourne Supremacy in which Jason Bourne uses his own passport and pops up on the grid?” says Jim Grace, an attorney for Baker Botts and an astute observer of the Capitol. “One of the agents tracking him says, ‘He’s making his first mistake.’ And another agent replies firmly, ‘It’s not a mistake. They don’t make mistakes. They don’t do random. There’s always an objective.’ Well, that’s how people think about Abbott and his campaign team. They don’t make mistakes.”

Still, the question remains: What should we expect from an Abbott administration? One afternoon, while traveling with him between campaign stops, I asked which Texas governors he would model himself after. He didn’t seem entirely comfortable with the question. In all the time I spent with him, he rarely paused to answer, but on this occasion there was a slight delay before he spoke: “My background is so completely different from previous governors that my administration will be unique.”

Long gone are the days when Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who contracted polio at the age of 39, worked diligently to conceal his paralysis from the public—and reporters covering him tacitly agreed not to write about his use of a wheelchair. Recently there have been several high-profile public officials who use wheelchairs, including current U.S. representative Tammy Duckworth, from Illinois, and former U.S. senator Max Cleland, from Georgia, both of whom were wounded during military service. But it is not all that common: the most recent governor in a wheelchair was Alabama’s George Wallace, the Democratic segregationist who was paralyzed by a gunman in 1972.

In speeches, Abbott refers to the accident as his toughest challenge: “What happened that day made it highly improbable that I would even be here today to get to speak with you.” It is also true, however, that in some sense the accident set him on the path to elective office. Had he never been paralyzed, he might well have ended up in the corner office of some Houston law firm, tallying up his billable hours and making reservations at the River Oaks Country Club. Instead, he became a man with something to prove.

Abbott was born in Wichita Falls in 1957, where one of his earliest memories is of playing in a sandbox in his backyard with his brother, Gary, when the tornado sirens went off. His father, Roger, was a proud University of Texas graduate who worked as a stockbroker and insurance agent; his mother, Doris, was a homemaker. His father’s father was a country preacher, and the Abbotts attended the First Christian Church.

At the age of six, Abbott moved with his family to Longview, where they lived for six years. Abbott played Little League baseball and Pee Wee football, joined the Boy Scouts, and fired a rifle for the first time. The sports memory that stands out the most was a game in which he was the starting pitcher. “I threw a one-hitter, but my team won by only a run, 10–9,” he says. “I lost track of the number of walks that day.” He celebrated the victory by getting a suicide with his teammates at a nearby snow-cone stand.

Roger and Doris enjoyed talking about politics; they were Republicans, and Abbott remembers a Barry Goldwater bumper sticker on the family car. The family moved again as he started junior high, this time to Duncanville, where he met the friends he has kept until this day. Abbott played football from seventh grade until tenth grade, but running track was his passion. He ran the eight-eighty (“This was back before the metric system,” he says with a laugh), and during his senior year he won every single track meet except one. He was also a strong student who participated in mock trial. When he graduated, he was voted Most Likely to Succeed.

The period had a dark spot, however. During Abbott’s sophomore year, his father died of a heart attack, which devastated the family. But it also gave him new admiration for his mother, who went to work in a real estate office to make ends meet. Abbott himself mowed lawns and worked at the local general store, where he stocked the shelves and cleaned the animal cages. After graduation, he headed to his late father’s alma mater, where he studied business and joined the Young Republicans’ Club. At the start of his junior year, he met a freshman named Cecilia Phelan, who had graduated from Thomas Jefferson High School, in San Antonio. Her parents, who greatly admired John F. Kennedy, were both middle school teachers. Cecilia also intended to be a teacher, and she had originally planned on going to Texas State University, in San Marcos. But she had been accepted to UT as well, and at the last minute she changed her mind. At the Castilian dormitory, in Austin, a late cancellation had opened up a room. Abbott was one of her new dorm mates.

A bright, outgoing girl, Cecilia had been playing classical piano since the age of six, and there was a mini grand piano on the main level. Playing in the evenings, she caught the attention of Abbott, whom she recognized as the guy who always carried a football around with him. “For some reason, Greg thought I was good,” she says with a grin.

Instead of dating, however, they became friends. In fact, in those first few weeks of the semester, Cecilia ironed his shirts before he went out on dates with other girls and coached him about what to say. When they realized that they shared the same birthday, November 13, their friends threw a party for them both, and that’s when the relationship began. Abbott started attending Mass with her at the University Catholic Center, and within two years, they were engaged. After Abbott finished his bachelor’s degree, they were married at Our Lady of the Lake, in San Antonio, in 1981 (Abbott would formally convert to Catholicism in 1987). He was accepted to Vanderbilt Law School, in Tennessee, and Cecilia put her degree on hold. Abbott proved once again to be an outstanding student, and after he earned his law degree, in 1984, he received a job offer from Butler and Binion, in Houston. The couple looked forward to starting their new life back in Texas.

On the steamy afternoon of July 14, 1984, Abbott took a break from studying for the bar exam with his friend Fred Frost, who had also graduated from Vanderbilt. They decided to go for a jog through River Oaks, one of the most affluent neighborhoods in the state. The crape myrtles were in bloom, and majestic live oaks and Southern magnolias filled the lawns of the stately homes. Along one section of Inwood Drive, the trees were so thick they formed a canopy over the street, providing a spot of shade to beat back the relenting heat. Only five minutes or so into their run, as Abbott and Frost approached the intersection of Inwood and Chilton Road, Abbott heard what he describes as a “loud explosion, like a bomb going off.” He had been running a few yards ahead of Frost, and the next thing he knew, he was down on the ground, having been struck by an oak tree that had snapped near its base. “It hit me in the back and knocked me down,” Abbott says. “It broke bones in my vertebrae, which pierced my spinal cord. I had fractured ribs, which poked into some of my organs. The pain was incomprehensible.” A few feet away, the tree had also crushed a parked Cadillac.

Frost dashed off to get help. Abbott lay on his back, unable to move. As he waited, he tried his best to cope with the pain. A single thought ran through his head: “This is what paralysis is like.” He felt as if rigor mortis had already set in. He had the sensation that his legs were frozen in the air, as if they were still in the runner’s position, so he reached out to try to push them down, only to realize they were flat on the ground. He was convinced that his career as a lawyer was over.

The paramedics drove him to nearby Twelve Oaks Hospital, but his ordeal was just beginning. As Abbott explains it, “Twelve Oaks at that time wasn’t so much a hospital as it was a clinic.” He says the doctors didn’t know what to do with him because they weren’t equipped to handle such serious trauma cases. He waited for five hours before he was finally transferred to Memorial Hermann Hospital—all the while going without any pain medication. At Hermann, the doctors quickly realized that their patient was now close to death, so they took him to the ER to stabilize him. Time was critical, so even before administering anesthesia, they performed a peritoneal lavage to determine the extent of his internal bleeding. “The nurse took my hand and said, ‘This is going to be bad. Turn your head,’ ” Abbott says. As they opened him up, Abbott felt sick and tried to vomit, but he didn’t have anything in his stomach, so he could only gag.

The doctors saved him, but they weren’t able to perform the surgery to repair his back for several days. “I had to live with these bone fragments in my spinal cord during that time,” he says. “If you took needles and poked them in your eye and lived like that for days, what was happening to me was even more painful.”

Eventually, the doctors reassembled his vertebrae, fused them together, and inserted two steel rods along his spinal cord. He stayed in the hospital for about six weeks before transferring to the Institute for Rehabilitation and Research. After spending another six weeks flat on his back, he was fitted with a body jacket—what Abbott refers to as his “turtle shell”—which he had to wear for several months.

“In my mind I could see what we were not going to have,” says Cecilia, who had always wanted a large family. “There was a grieving process for what was lost, for everything that went away. It’s funny, because looking back, I remembered that before the accident we had watched a television movie together starring John Ritter. His character fell off a horse and was disabled, and I very clearly remember Greg saying, ‘I don’t think I could do that.’ It shows how strong you can be when you have to.”

Both Greg and Cecilia agree that the tragedy made them more determined. “The accident brought out the work ethic my parents had instilled in me,” Abbott says. “I was still wearing the body jacket and learning how to move around when I went to work at the law office. I wasn’t even able to wear a suit. My bosses loved that, because just think what it did for anyone with an excuse for not getting their job done. But I’ll tell you this astonishing fact: Cecilia and I believe our lives are better after the accident than before. I think there’s a greater appreciation for life.”

When I asked him whether he ever replayed the moment in his mind, he answered firmly, with a hint of defiance: “Not once. I have never thought, ‘What if I’d been a minute faster? Or a minute slower?’ There were people at the rehab center whose sole focus in life was that they were going to walk again. But the doctors told me, ‘Here’s the reality: it’s not going to happen.’ So I made a real quick adjustment. Instead of grasping for hope about walking again, I immediately started focusing on being as good as I could be without walking.”

When Abbott’s gubernatorial campaign kicked off this summer in San Antonio, the location was full of personal meaning. Cecilia’s parents still live in the house she grew up in, and Plaza Juarez, where the announcement was held, is not far from a bridge on the River Walk where Abbott proposed to her back in college. But the most important part of the announcement was the date. It was July 14, exactly 29 years after the accident.

Abbott’s announcement demonstrated that he intends to make his disability a cornerstone of his campaign. For that strategy to work, the candidate and his family have to find the right pitch between seriousness and humor or risk having the wheelchair make him seem unapproachable. Abbott and Cecilia, along with their sixteen-year-old daughter, Audrey, whom the couple adopted when she was born, all seem genuinely comfortable with the subject. At a recent stop in Duncanville, Audrey told an overflowing crowd that her father had dressed up in some “outrageous” Halloween costumes over the years, including a grocery cart and an Army tank. Even the accident itself is fair game. When talking to supporters at another rally, Abbott remarked, “You must be wondering how slow I was jogging to get hit by that tree.”

It’s sometimes the case that other people are more sensitive about it than Abbott is. During an anti-abortion rally at the Capitol on July 8, Jason Whitely, a senior reporter for WFAA-TV, in Dallas, tweeted, “Greg Abbott says he’s here ‘standing for life’ even though he’s in wheelchair.” By that evening Twitter was pulsing with irate Republicans accusing Whitely of insensitivity, including consultant Rob Johnson (who is working on state senator Glenn Hegar’s campaign for comptroller) and Erick Erickson, the editor of the conservative website RedState.com, who fired off a post called “@JasonWhitely of WFAA-TV: Jackass of the Day or Jackass of the Year?” The anger didn’t subside until Abbott, who is more active on Twitter than any other statewide official, jumped in to defuse the situation, tweeting, “Hey Friends, it was me who said ‘I may be in a wheelchair, but I #Stand4Life.’ @JasonWhitely was just quoting me.”

Abbott does not use a motorized wheelchair, so, like FDR, he has a strong upper body, which comes through in a powerful handshake. At the San Antonio event, he wheeled himself across the stage effortlessly, and he is incredibly skilled at moving from his chair into a vehicle, for example, or negotiating uneven ground. In 2008 he gave the commencement address at Prairie View A&M University. That day marked the largest graduation class in the university’s history—more than eight hundred students—and what the faculty and administration remember is that Abbott chose to participate in the photos as well, rolling his chair back each time a name was announced and then forward for the photograph. He moved his chair more than 1,600 times over the course of several hours.

Still, the disability presents obvious difficulties. Earlier this spring, after a tornado ravaged the Rancho Brazos Estates subdivision, in Granbury, I watched Abbott tour the damage with Governor Perry, Hood County sheriff Roger Deeds, and other officials. A lectern was positioned in the middle of a road—or what had been a road 48 hours earlier. Lecterns pose a problem for Abbott because they tend to hit him at chin level. So after Perry spoke, Abbott had to come around to the side to address the media, saying what has become a signature line for him: “Texans may get knocked down, but they always get back up.”

Afterward the group inspected what was left of the homes, and a telling scene unfolded. Perry, who is often at his best in situations like these, was embracing people he encountered, even kissing a Red Cross official on the forehead. With Abbott, however, the wheelchair created a cushion of space around him that few people penetrated. He greeted everyone warmly and expressed sincere concern, but there was often a noticeable distance between him and the group.

There is another way in which Abbott’s disability could be a campaign liability. Among Democrats, there’s the lingering feeling that the attorney general is a hypocrite, or worse, for having supported tort reform in Texas after he himself did not hesitate to sue the homeowner in River Oaks whose property the oak tree was on and the maintenance company that had failed to determine that it was rotting. The tort reform movement began in earnest during George W. Bush’s 1994 campaign for governor, but it wasn’t until the 2003 legislative session—Abbott’s first as attorney general—that much stricter regulations were put into place, limiting, for example, the payout for noneconomic damages such as pain and suffering to $250,000 in medical malpractice cases. Abbott supported this reform, but his own suit—which was not for malpractice—was settled for roughly $11 million, adjusted for inflation. During the 2002 race, Abbott attacked his Democratic opponent, Kirk Watson, for being a trial lawyer; an attorney who had worked on Abbott’s settlement promptly lashed out at him for being unfair.

The facts are these: in his settlement, Abbott received a variety of tax-free payments: an immediate $300,000 cash award; monthly payments of $5,000 that began in November 1986 and increase each year at a rate of 4 percent compounded interest; and periodic payments that began in November 1987 and will continue until 2022 (the next such payment will occur on November 1 in the amount of $400,000).

For his part, Abbott flatly denies that there is any conflict between his own case and his efforts to limit frivolous lawsuits. He points out that he did not sue for punitive damages and that a person in the same situation today as he was back in 1984 would still have the opportunity to claim the same award. I sought out Southern Methodist University law professor Bill Dorsaneo, an expert in tort reform cases and the principal author of the 26-volume Texas Litigation Guide, for some perspective. Dorsaneo says he rarely agrees with the attorney general’s opinions about tort duties and causation, but he concurs with Abbott’s view of the settlement.

“General Abbott’s case is not a very good example of the differences between cases then and now,” he told me. “Except for the fact that insurance companies did not expect to get favorable treatment from the appellate courts until sometime in the nineties and were more inclined to settle weak liability cases then than now, there is not much about Abbott’s settlement that seems unusual under today’s legal standards.”

Abbott dismisses the controversy soberly: “I would give back every penny of that settlement if I could dance with my wife and walk my daughter down the aisle.” In fact, if there’s anything about his candidacy—and his potential governorship—that could wind up transforming his party, it’s the idea that he is, in a visceral, obvious sense, a victim. At a time when the Republican party is working to expand its appeal—to the booming Hispanic population, among others—his story of tragic loss and the perseverance that has enabled him to overcome it makes him more relatable than most major Republican candidates in Texas. With the exception of Ted Cruz (Hispanic, son of an immigrant), the candidates the GOP has recently put forward—Perry, Dewhurst, John Cornyn, Joe Straus, Susan Combs, and Kay Bailey Hutchison—present a familiar image of great good fortune and comfortable success. Greg Abbott does not. His message is that he has succeeded because of sheer will, and you can too.

As a young lawyer at Butler and Binion, Abbott became famous for the amount of hours he put in—and for the exacting detail he brought to his cases. “I worked so hard to prepare for a case,” he says. “And it would be so disappointing when I realized the judge hadn’t read any of my materials.” It’s telling that it was this disappointment that propelled Abbott into his first political race. In 1992, sick of underprepared judges, he ran for judge himself and won. On the bench he developed a reputation as a demanding jurist who strictly interpreted the law, and he soon caught the attention of then-governor George W. Bush, who appointed him to the Texas Supreme Court. Abbott ran successfully for reelection twice, then set his sights on the lieutenant governor’s office. In 2001 his campaign had been up and running for months, but then Cornyn, the attorney general at the time, announced he was going to run for an open U.S. Senate seat. Abbott changed course, in part because his legal and judicial experience suited him to the job and in part because he wanted to avoid a primary fight. Abbott was uncontested in his primary, and in November, along with the rest of the Republican ticket, he won handily.

His first order of business was public safety. He expanded the office’s law enforcement division from approximately thirty people to more than one hundred and created a new division called the Fugitive Unit to track down convicted sex offenders in violation of their paroles or probations. “We’ve taken thousands of them off the streets,” Abbott says. “It’s impossible to calculate how many women and children have not been raped because these people were locked up.” And he spearheaded the Cybercrimes Unit to respond to the growing number of child predators using the Internet to pursue their victims. “We have developed such a good reputation and skill set in criminal prosecutions that when accusations were raised about the sexual assault of children at the Yearning for Zion Ranch, in Eldorado, we were the ones to step in,” he says. “As a result, we successfully prosecuted eleven people, including the group’s leader, Warren Jeffs.”

But he is best known for his battles with the federal government. In 2003 he responded to a class-action lawsuit over waiting lists for services for disabled Texans by taking an unexpected position, arguing that a key component of the Americans With Disabilities Act was unconstitutional. (He lost that case.) In 2005 he fought a lawsuit contending that a Ten Commandments monument on the grounds of the Capitol was unconstitutional. The case made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where Abbott successfully argued that the monument did not violate the Establishment Clause of the Constitution.

The Obama administration has provided his greatest political piñata. Since 2009 he has filed suits against the president’s Environmental Protection Agency, his Department of Health and Human Services (including challenges to Obamacare), and his Department of Education, to name a few. To be sure, there is a clear political upside in taking on these fights; no Republican in Texas ever went broke defying Obama. But as former governor Mark White, who just happens to be the last Texan to make the jump from attorney general to governor, told me, “A lot of people misinterpret the attorney general’s office. They think he’s the lawyer for the people, but that’s not true in a direct sense. His job as a constitutional officeholder is to represent the State of Texas, so he becomes the lawyer for the governor, the lieutenant governor, and so on.”

It’s a role that has sometimes led him into treacherous waters. Tom Pauken, Abbott’s primary opponent, has taken him to task for his role in CPRIT, the embattled cancer fund that has come to be seen as the epitome of crony capitalism. “Abbott served on the oversight committee, but he never attended one meeting,” Pauken says. “There were all kinds of questionable grants, and then he turns around and gets millions in contributions from individuals who benefited from those grants? That is a huge breakdown in fiduciary responsibility.”

But the most explosive issue may come over voting. In 2011 Republicans passed new redistricting maps as well as a contentious voter ID bill that would require most prospective voters to show photo identification. Both got instantly hung up in the machinery of the federal courts, as everyone expected they would be. Because of a provision in the Voting Rights Act, states like Texas, with a history of discriminatory practices, cannot make any changes to their voting laws or procedures without the approval of the federal government, a process known as preclearance. In the case of redistricting, Abbott had a choice: he could seek approval from the Department of Justice, which had become the usual option over the years, or he could go before a three-judge panel in Washington, D.C. Abbott chose the latter, and the judges kicked the maps back, claiming that they hurt minorities, particularly Hispanics, whose numbers had increased by 41 percent over the previous decade. It was a major blow to the attorney general and the GOP’s new maps.

“There hadn’t been a finding of intentional discrimination since 1973,” says Michael Li, a Dallas-based lawyer who writes an influential blog called Texas Redistricting and Election Law (the site is more fun to read than it sounds). “The optics were bad because there were two Republican-appointed judges on the panel, so it looked like a neutral finding. If the DOJ had done it, Abbott could have said the ruling was political.” Abbott was incensed at the ruling, calling the decision “judicial activism at its worst.”

That set off a complicated chain of events involving multiple jurisdictions, several teams of lawyers, and countless headaches. A federal court in San Antonio drew a new set of interim maps that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where Abbott’s fortunes reversed. “I did something no one else has been able to do: I got Justices Sotomayor and Kagan to agree with Justices Alito and Scalia,” he says, referring to two of the high court’s most liberal and conservative members, respectively.

The state limped through the 2012 elections—the primaries were delayed by two months because of all the lawyering going on—but Abbott saw an opening to formalize the maps earlier this year. The Supreme Court was hearing a voting case out of Alabama that he believed would strike down Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, which provides for preclearance. If that provision fell, Texas would be free to make any changes it saw fit to its voting procedures without federal oversight. Abbott encouraged Perry and the Legislature to take up the maps in a special session, when parliamentary rules are relaxed and controversial bills have a greater chance of passing. Sure enough, the interim maps were passed in mid-June.

A few weeks later, Abbott relished the vindication: the Supreme Court struck down a key provision of the Voting Rights Act, and Abbott claimed victory, saying that both the maps and voter ID were in full effect. “Some people were critical of my decision to go before the district court in D.C. instead of the DOJ,” he says. “But the DOJ would have rejected the maps, and we would have found ourselves in court. My way saved us a step, and I’ll be the attorney general who got us the maps faster than anyone.”

Except that several weeks later, U.S. attorney general Eric Holder showed that he was just as willing to return fire. Holder now insists that Texas should be subject to federal preclearance for another ten years, and in late August he filed a suit to block voter ID from going into effect. The battle is joined, and Abbott is ready to lead yet another charge.

The long-running feud has opened a deep level of resentment among Democrats, who see Abbott as not defending the law but instead purposefully trying to suppress turnout by excluding voters—voters, it just so happens, that Democrats believe are more likely to vote for them. It’s an issue that the Democratic nominee—perhaps state senator Wendy Davis—will try to use against him. Yet all of this controversy, by and large, has been good for Abbott’s political ambitions because it energizes the conservative base. As White explained to me, “The attorney general’s office can be a springboard to the governor’s office for a couple of reasons. Most important is, you get to sue on behalf of the State of Texas, and usually that’s a popular suit. And when you’re defending on behalf of the State of Texas, usually you’re out there saying, ‘By God, I’m defending the State of Texas.’ And that’s a popular issue as well.”

Storm clouds were gathering outside the window of Abbott’s chartered jet as it approached Wichita Falls for a July rally on the front lawn of the house he lived in as a young boy. Sitting across the aisle, I pressed him for details about what kind of governor he would be. What previous governors did he admire? Instead of answering the question directly, he talked about overcoming the accident, then discussed his time as a judge.

I doubled-down: Is there a specific aspect of a previous administration that stands out to you? John Connally and his commitment to higher education? Allan Shivers and his defense of the

Tidelands? Pappy O’Daniel and the Light Crust Doughboys?

Abbott was not interested. Instead, he answered as broadly as possible: “I would hope there would be a common thread, a theme, if you would, about a commitment to the best interest of Texas. I think anyone who is governor has that attitude.”

He was no more specific when the conversation turned to Rick Perry, who has dominated state politics in a way that no other governor in Texas history has. Abbott is squarely in line with two of the main narratives of the Perry administration: provide a low-tax, low-regulation business environment to encourage economic growth and fight a no-holds-barred war against the perceived overreach of the federal government. When asked about differences between the two men—or perhaps even criticisms of the current governor—Abbott was careful, finally identifying two areas where he believed Perry himself had overreached: the Trans-Texas Corridor and the executive order that mandated that young girls in the state receive the HPV vaccine. The choices were not unexpected. In fact, they were downright safe, confirming what Jim Grace had said about how careful the campaign is. Then Abbott, acutely aware of the state’s Perry fatigue, moved away from the conversation entirely, saying, “I’m not inheriting the same state that we were a year ago. And I’m not going to be focused on what happened yesterday.”

Yet Abbott’s joint appearance with Perry in Granbury only fueled the belief that he had the governor’s backing. After Abbott’s remarks, delivered to the side of the lectern, Perry congratulated him and patted him on the shoulder, leaving his arm there for a short time as other officials addressed the media. A closeness has developed between the men over the years, and they talk weekly and get together about once a month. This summer they played a late-night game of cards on the porch at the Governor’s Mansion with other Republican officials and operatives, including U.S. senator Ted Cruz. Despite all of that, Abbott did not mention Perry’s name a single time during his announcement in San Antonio, a surprising fact when one considers this transitional moment in the state’s political history.

With Wichita Falls coming into view, I asked Abbott if he expected Perry to endorse him.

“I can’t play political pundit on stuff like that,” he said.

“Would you seek his endorsement?”

“I hope to get the endorsement of all Texans,” he said.

Still, most of his ideas sound awfully

similar to the current governor’s. Like Perry, Abbott complains that the border is not secured—and until it is, activity among the cartels will threaten not only the public safety but also the state’s economy. To address this “failure of the federal government,” he would support a bill in the 2015 Legislature to authorize more agents along the border. Like Perry, he wants to see transportation needs addressed, though he’s vague on the details. And like Perry, he wants the Legislature to be more transparent when it comes to

spending taxpayer dollars.

And of course, just like Perry, he also spends a great deal of his time fighting the federal government. This, in fact, may be the place where he’s willing to speak most openly about the transition. “We’ve been going through a process for the past four years that’s dangerously challenging,” he says. “We need to push back against unprecedented intrusion by the federal government. And so it’s a natural transition of going from being a general on the battlefield to pursuing the position of the commander in chief while waging that same war.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Rick Perry

- Greg Abbott