JANE NELSON IS A CHEERFUL, BLOND MOTHER OF FIVE who got her start in politics the same way most Republican women of her era did: stuffing envelopes for U.S. senator John Tower, a trailblazer for the Texas GOP. Elected to the Texas Senate from Flower Mound in 1992, she has spent the past eight years loyally promoting her party’s conservative causes with a certain Doris Day perkiness. But since July 24 she has been on the political warpath. And who is the target of her wrath? Spendthrift liberals? Misguided do-gooders? Partisan Democrats? None of the above. Try Attorney General John Cornyn, comptroller Carole Keeton Rylander, and land commissioner David Dewhurst—all Republicans.Cornyn, Rylander, and Dewhurst formed a three-member majority of the Legislative Redistricting Board who voted to eviscerate Nelson’s district in drawing the new boundary lines for the Texas Senate that, unless a court intervenes, will take effect for the 2002 elections. “Oh, I’m mad. Believe me, I’m mad,” Nelson says. “Things that are so blatantly wrong just drive me nuts. I have never been so mad about anything in my entire life.”

Nelson is not alone. Nine of the sixteen Republican senators strongly object to the new map. Some are angry about their own districts. Others object to the secretive process used by the mapmakers. Many are willing to speak for the record in blunt language seldom heard from politicians, particularly in a party whose Eleventh Commandment, promulgated by Ronald Reagan, is “Thou shalt not speak ill of a fellow Republican.”

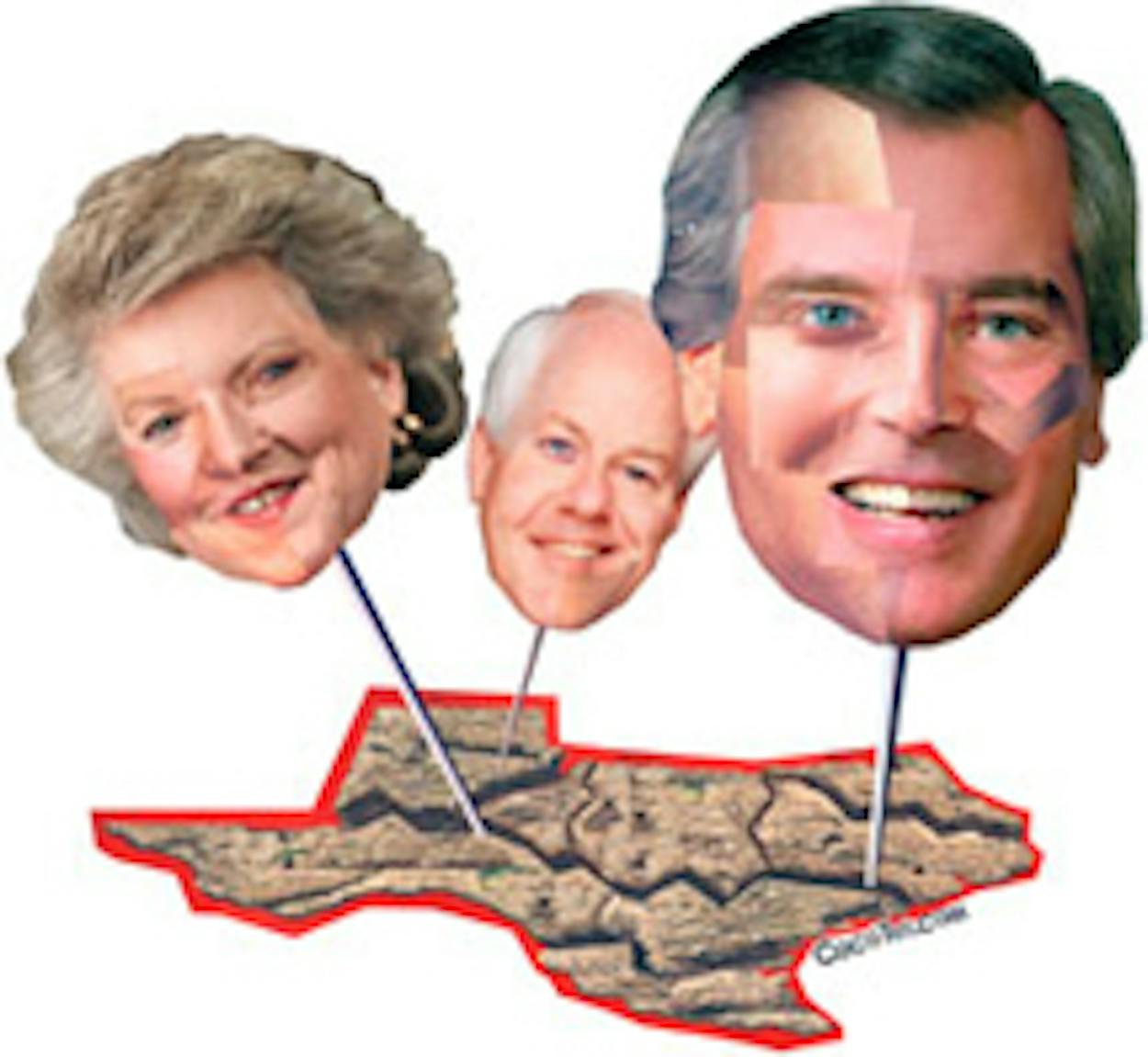

What should have been a moment of unvarnished glory for the Texas Republican party—its long-awaited takeover of the Legislature—has turned into a Shakespearean family feud, complete with charges and countercharges of greed, deceit, villainy, and vanity. The redistricting process lifted a veil on the behind-the-scenes power struggles within the state GOP since the ascension of George W. Bush to the presidency. Without Bush and his political architect Karl Rove to orchestrate Republican politics, a battle has raged between two loosely defined factions: the “grass roots” (legislators and their local GOP constituencies) and the “big shots” (statewide officials and the party’s major financial benefactors).

No one, least of all the GOP senators, foresaw that redistricting would turn Republican against Republican. Drawing political lines has traditionally been a process in which the dominant party (heretofore Democrats) attempts to maximize its electoral prospects through imaginative cartography. As the Legislature wound down last May, Republican senators killed a plan to redraw district boundary lines for that body. After all, they reasoned, why negotiate with their Democratic colleagues when, according to the state constitution, they could simply let the Republican-dominated Legislative Redistricting Board (LRB) do the job for them?

On July 24 that question was answered. Cornyn, Rylander, and Dewhurst voted for a Senate map—over the objections of the board’s other two members, Republican lieutenant governor Bill Ratliff and Democratic House Speaker Pete Laney—that was dramatically different from anything considered during nearly two years of debate and public hearings on the issue. Among the biggest losers: many of the Republican senators. “The plan was posted on the computer that morning. I was stunned. Never in any plan was this scenario ever discussed,” Nelson recalls. “I picked up the phone and called all three of them and said, ‘You can’t do this.'” But they could.

Many Republican voters in Nelson’s Ninth District (between Dallas and Fort Worth) had been sucked into the nearby Twelfth District to make that Fort Worth district more Republican. It didn’t take long for Nelson to figure out why: Dee Kelly, Jr., son of the Fort Worth attorney who is the longtime consigliere to the megawealthy Bass family, announced he would run in that district. An outraged Nelson decided to follow her voters and announced that she too would run in the Twelfth District—but not before airing her objections to Cornyn. The attorney general, she says, responded: “Don’t complain; you still have a safe [Republican] district.” But Nelson wasn’t mollified: Not only were her longtime constituents moved from her district, but 19 of the 25 small towns—including her hometown of Flower Mound—were split in two.

“This is not about me. It’s about the people I represent. You can’t divide these communities,” Nelson says. Had advance notice been given that the LRB was considering such a move, she adds, “people would have been down [to testify in Austin] in busloads. This was not done for partisan reasons; this was done because people with a whole lot of money had a whole lot of influence,” she says.

For the record, Kelly Junior has publicly denied exerting influence on the LRB to get the district that looks custom-tailored to his interests. And comptroller Carole Keeton Rylander says it is “hogwash” to suggest that big donors affected the outcome of any redistricting decisions. But Republican state senator Jeff Wentworth, of San Antonio, who chaired the Senate redistricting committee and failed to win enough votes for the Senate to debate his redistricting plan, says he had a cell phone conversation with Cornyn on the morning of the vote urging him to adopt an alternative map proposed by Ratliff. Emphasizing that he is a longtime friend and supporter of Cornyn’s, Wentworth says that the attorney general told him he was getting “significant pressure from major donors in Dallas and Houston” to adopt a map that guaranteed more Republican influence.

“I told him, ‘Don’t give in,'” Wentworth says. “I felt betrayed. I put my heart and soul into trying to avoid exactly this result—it will cost the taxpayers of Texas millions of dollars fighting over this map [in court] now.” He recalls that Republicans loudly complained when Democrats rammed through a highly partisan map in 1991; now his party was doing the same thing. “It is hypocritical, and it is sorely disappointing to me,” he says.

Cornyn’s political consultant, Ted Delisi, vehemently denies Wentworth’s account of the conversation, calling it a “grossly inappropriate and inaccurate statement. I am very surprised he would stoop that low.” He also suggests that Wentworth’s criticism of the LRB is grounded in his failure to win legislative approval of his own redistricting plan. “He fumbled it [the redistricting issue] badly,” Delisi says. As for the GOP senators’ complaints that they did not have the opportunity to comment on the map that was adopted, Delisi says, “Were they called in and invited to hold hands and sing ‘Kumbayah’? No, they were not.”

Instead, he insists, the lines were drawn to comply with the extensive body of law governing redistricting decisions. Under the Voting Rights Act and case law, the LRB had to ensure that districts didn’t dilute the strength of minority voters and were drawn compactly to keep “communities of interest” intact, among other considerations. “The legal requirements are what drove the train,” Delisi says.

And yet Nelson’s complaints about the apparent influence of the big shots are repeated throughout the state. In West Texas, state senators Teel Bivins, of Amarillo, and Robert Duncan, of Lubbock, held a series of meetings over several months with community leaders from their districts and drafted a plan for their area of the state. Duncan and Bivins testified in favor of their plan before the LRB on July 17 and assumed the issue was settled. Then, “Whack, out of the blue,” Duncan says, that plan was tossed out by the LRB in favor of one proposed by Rylander.

The effect of the new plan, which moved six counties from Duncan’s district to Bivins’, is to shift dominance of the district from Amarillo to Midland, home to many large GOP contributors. Duncan believes the change was engineered by state representative Tom Craddick, of Midland, who hopes to end Laney’s five-term run as Speaker and win the office himself. Craddick, Duncan says, “coordinates important fundraising efforts for the party. This is about political influence, those people who finance campaigns.”

Rylander says she offered the change to make the district “more balanced.” As for Craddick’s involvement: “I didn’t even talk to him about that district. No deal was struck anywhere by anybody.” But on July 18—two days before the LRB proposal was made public—Craddick told a gathering of Young Republicans in Midland that he thought “there was a good shot” the LRB would approve a plan giving more influence to the Permian Basin, by shifting six counties from Duncan’s district. He then described the plan that Rylander offered.

Local officials in the affected towns—like Big Springs and Amarillo—unanimously opposed the changes under the LRB plan, Duncan says. “My area of the state was arrogantly ignored, and I’m not going to get over that.” He’s not alone: Bivins’ mother promptly canceled a fundraiser she had promised to host for Cornyn.

In Dallas, Senator Florence Shapiro, of Plano, lost all of Highland Park and University Park—and some big-time GOP donors—from her district after Park Cities officials and longtime Republican contributor and power broker Louis Beecherl lobbied for a district representing primarily those wealthy Dallas enclaves. Beecherl contributed $10,000 each to Cornyn, Rylander, and Dewhurst in June. Though Shapiro says she ultimately was given “a great district,” she was “unhappy about the process” since the changes were sprung on her the day of the vote: “The process itself left a lot to be desired. The LRB chose for whatever reason not to listen to the concerns of legislators, who know and understand their districts. We were shut out of the final process completely.”

When asked if Beecherl influenced the map, Delisi declined to “speak about conversations that may or may not have happened. A great many people were interested in redistricting. Louis Beecherl is the patron saint of the Republican party, a benefactor of the Republican party. I’ll bet he’s interested.”

If it is any consolation to the Republican senators, the LRB treated Democrats even more shabbily. When Laney arrived for the first meeting, all of the members of the panel had nameplates at their seats—except him. On July 24 Dewhurst offered an amendment never before laid out in public that redrew Laney’s district to look like—in the words of one legislative aide—”an upside-down swastika.” It was approved by the Cornyn-Rylander-Dewhurst trio, once again over Laney’s and Ratliff’s objections. And when was this proposal first disseminated to the public? When it was posted on the LRB Web site at six-thirty that evening, a few hours after its adoption.

Delisi predicts the flap will blow over soon. But the healing process may take a little longer. Traditionally, statewide candidates have been able to count on a grassroots network of legislators to promote their campaigns. Just how enthusiastic will the bruised lawmakers be in 2002?

“I don’t have the zeal for it,” Duncan says. “I think it is going to hurt this election quite a little bit.” He is particularly pointed about Dewhurst, who, if he is elected lieutenant governor, will need the consent of the Senate to hold on to the office’s traditional powers. When the LRB considered Rylander’s proposal to help Midland, Duncan thought he had an agreement with Dewhurst to support leaving Big Spring in Duncan’s district. But Dewhurst voted “present” and the attempt failed in a 2-2 deadlock. “If that’s the kind of lieutenant governor he’s going to be—that he can’t make a decision or is so influenced by political concerns—then I have a real problem with that,” says Duncan.

When I started to ask Shapiro the same question about her enthusiasm for the GOP ticket, she interrupted me. “I know exactly where you are going,” she said. “I can’t tell you. I’d like to wait and see. I was very disappointed in the manner in which those three handled themselves.”

To Nelson, the family squabble shows that Texas Republicans are stuck in an awkward “adolescent phase.” “The party hasn’t matured,” she says reflectively. “There’s a real vacuum, and I think that is how this happened. Unfortunately it was being filled by sources that did not have the party’s best interest foremost.” Whose interests were foremost? Well, Cornyn, Rylander, and Dewhurst all had ambitions for higher office; since the map was adopted, Cornyn has announced for the U.S. Senate seat being vacated by Phil Gramm, and Dewhurst is trying to move up to lieutenant governor, succeeding Ratliff. By currying favor with the big shots, they could enhance their own ability to raise money. But a family feud has never been resolved by asking the question, What’s in it for me?