It’s not often that I have acid flashbacks to the old Southwest Conference—that shady enterprise about which our own Gary Cartwright once wrote “one of its member schools was usually on probation and the majority of its players free on bond.” But this summer, while savoring the latest bit of college-football chicanery, I found myself at a loss for words. The University of Oklahoma—which itself has an illustrious history of cheating—was hauled before the NCAA. As had been revealed last year, three Sooners players—including starting quarterback Rhett Bomar—had accepted money from a Norman car dealership for work they hadn’t performed. The dealership, the felicitously named Big Red Sports and Imports, was owned by one of the school’s boosters. This was a big no-no, and though OU’s punishment was hardly as draconian as some of the sentences handed out in the old SWC days (the Sooners lost a few scholarships and forfeited all of their 2005 wins), it provided no shortage of satisfaction for the schools in the lower half of the Big 12 peninsula. For it had been made official: The Sooners, the reigning conference football champs, were cheaters.

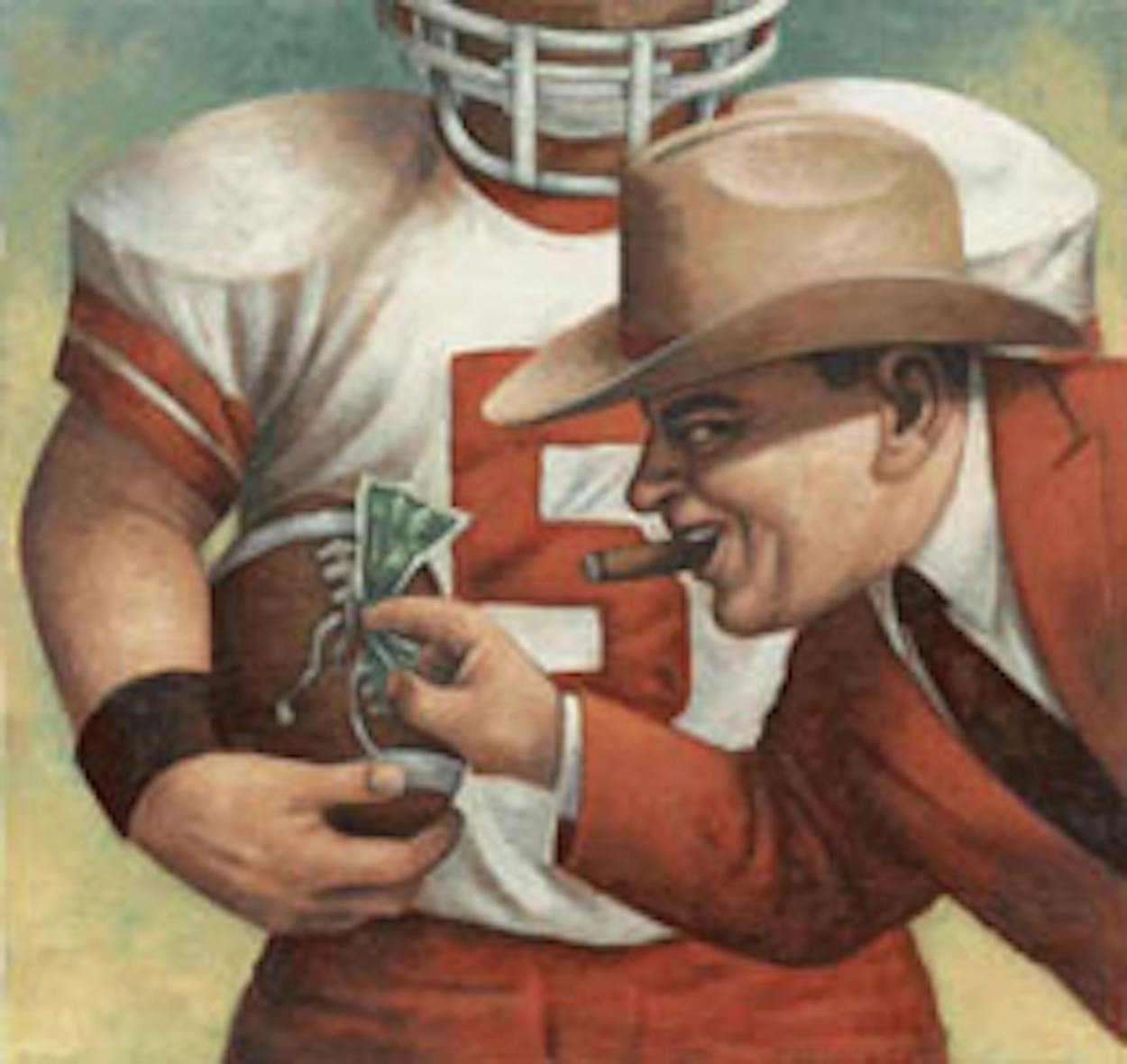

It’s been some time since a Texan could look northward with such intense schadenfreude (actually, about a year, when the Sooners basketball team was hauled before the NCAA for recruiting violations). And there’s good reason for that: The essential nature of cheating in college football has changed. Once you would shudder that a school’s boosters were lining the pockets of eighteen-year-old high school recruits to get them to play for State U. There were rumors of envelopes bulging with $100 bills, new cars parked next to off-campus apartments, unworked summer “jobs” of the Norman variety—and many of the rumors were true. But OU’s recent transgressions aside, college football has moved away from the classic style of cheating and into a different kind of money culture. And it’s worth asking: What does cheating mean these days, anyway?

This being a family magazine, we needn’t get too deep into the sordid history of the Southwest Conference, other than to note that with each passing year the sum total, if not the brashness, of the cheating is staggering. In short: In the eighties, seven of the conference’s nine teams were put on some kind of probation, most memorably Southern Methodist University, which received the so-called death penalty (no football program for one year, no home games the next). In 1987 Bill Clements, a former member of SMU’s board of governors who had just been elected Texas governor, publicly confessed to approving the creation of a $61,000 slush fund to benefit Mustang athletes. Clements insisted that the improper payments would not be stopped but “phased out” over a period of years. Only in the Southwest Conference could one appeal to morality and insist that a defensive end keep receiving his ill-gotten recruiting money.

But the landscape has changed quite a bit since then, and not just because the Southwest Conference dissolved in 1996. The NCAA, too, has changed. The NCAA has become convinced it doesn’t have the legal power (it can’t issue subpoenas) or the manpower to review every single transaction that goes on between athlete and booster. It now primarily relies on institutions to police themselves and self-report their own infractions. This is a Faustian bargain many fans have scoffed at. They point out that when violations are unearthed at a major program, like Oklahoma or Southern California, the NCAA hands out only a meager penalty, if any. Moreover, when it does act, the NCAA is concerned mostly with niggling infractions—exactly when a coach can meet with a recruit, exactly when a coach can call a recruit, or, lately, regulating coach-to-recruit text-messaging. More and more, the NCAA seems like a paper tiger.

This would seem like an invitation to return to the free-for-all eighties but for two bigger changes. The first is what we might call the U.S. News & World Report effect, or the influence of academic rankings. While college presidents of old might have entertained a bit of trickery at the cost of the university’s prestige, the new breed will not. Robert Gates, the former Texas A&M University president who is now the U.S. Secretary of Defense, might view A&M as a more inclusive institution, but this vision would almost certainly not have room for coach Jackie Sherrill, who got the Aggies slapped with probation in 1988. Or note, for example, the four arrests this summer of University of Texas football players, like Robert Joseph and Sergio Kindle (alleged offenses ranging from robbery to driving under the influence). That had Mack Brown scrambling like Vince Young to preserve the program’s—and thus the university’s—image; he suspended some players and threw another off the team. Football might be king here, but it is no longer big enough to risk besmirching a school’s name.

The second change is more incognito: the rise of college-football message boards, which have affected the sport in ways that we are only beginning to understand. On Web sites like TexAgs.com and Orangebloods.com, a few thousand pseudonymous football fans gather each day to chatter about their alma maters. Another component of the Web is alma mater muckraking—the ongoing amateur sleuthing into the doings of one’s rival schools. Indeed, the first mention anywhere of the Oklahoma scandal was posted on TexAgs on January 30 of last year. A poster calling himself “aggiegrant06” reported that his girlfriend worked at a large car dealership and had seen paychecks intended for football players who didn’t actually work at the dealership. When Oklahoma self-reported its findings a few months later, it became clear that TexAgs had inadvertently broken the biggest college-football scandal since Barry Switzer roamed the earth. Though many of the charges aired on these sites turn out to be bogus, with the Web it seems less likely that a $500 envelope or new Cadillac SUV could change hands without arousing the antennae of a vigilant fan.

So if cheating has changed, what we should be worried about is the new money culture in college football. All over Texas, schools have begun to lavish money on recruits in a whole different way: by building athletic bunkers to house them in. It has become part of the recruiting ritual to show the athlete around campus and blow him away with affluence: UT’s athlete lounge has leather-paneled walls and big-screen TVs; A&M recruits have been marveling lately at the recently opened indoor practice facility. There is a reason for this new arms race, and it also comes from Oklahoma: Oil tycoon T. Boone Pickens has donated more than $250 million to Oklahoma State, much of which went to the athletics department; OU, for its part, has promised million-dollar upgrades to its facilities. The idea is that a visiting recruit will be getting monetary “value” by attending college, if not money-filled envelopes themselves.

The money comes from huge TV contracts, bowl payouts, and of course, generous boosters. In a sense, you have a dynamic similar to that of the Southwest Conference days: “amateur” athletes, many of them from poor backgrounds, surrounded by a culture of wealth. And yet instead of the booster handing an envelope to the recruit, the booster is handing a (much bigger) envelope to the university, which then buys a big-screen for the recruit and sets it up in a leather-paneled lounge. It’s not cheating, exactly, but nor can it be called amateurism.

I’ve never been particularly squeamish about college athletics, but it strikes me that as more money rolls in, the more gross the divide between athlete and university becomes. Perhaps it’s time to revisit the question of the paid college athlete—a small stipend, something. Otherwise, you might as well get the players jobs at car dealerships and call us Oklahoma.