Dear Cormac,

A couple of years ago the Texas Book Festival “Bookended” you. (They will Bookend anybody, so it’s nothing to feel cocky about.) Since you famously do not appear in person to receive awards and over the years have kept yourself as invisible as some desert derelict living under a bridge near Lordsburg, New Mexico, I was asked to say a few words on your behalf. This required me to give up my regular Saturday morning muni golf match, but I reluctantly agreed. I did this out of the goodness of my heart, without expectation of any small thank you gift, such as a turquoise string tie, a Santa Fe Institute coffee mug, or a sleeve of Titleists. People who pray to Jesus don’t expect trinkets either. I trust, by the way, that you eventually received the tokens of the festival’s affection. You can’t miss them—two huge lumps of limestone weighing a combined thirty pounds, each one engraved with an image of a cowboy hat with a book for its crown. Hard to imagine what it costs to ship those suckers or what somebody like you would do with them.

In my remarks to the swells at the book festival I depicted you and me as buddies who e-mailed each other all the time. Maybe they believed me. I said that you always began with “Hi Don” and tried to pass yourself off as some macho dude just back from a weekend of tequila-crawling in Juárez but that I knew differently. I knew that you really spent your weekends peddling Blood Meridian T-shirts on the plaza in front of the cathedral in Santa Fe.

Turns out I wasn’t that far off.

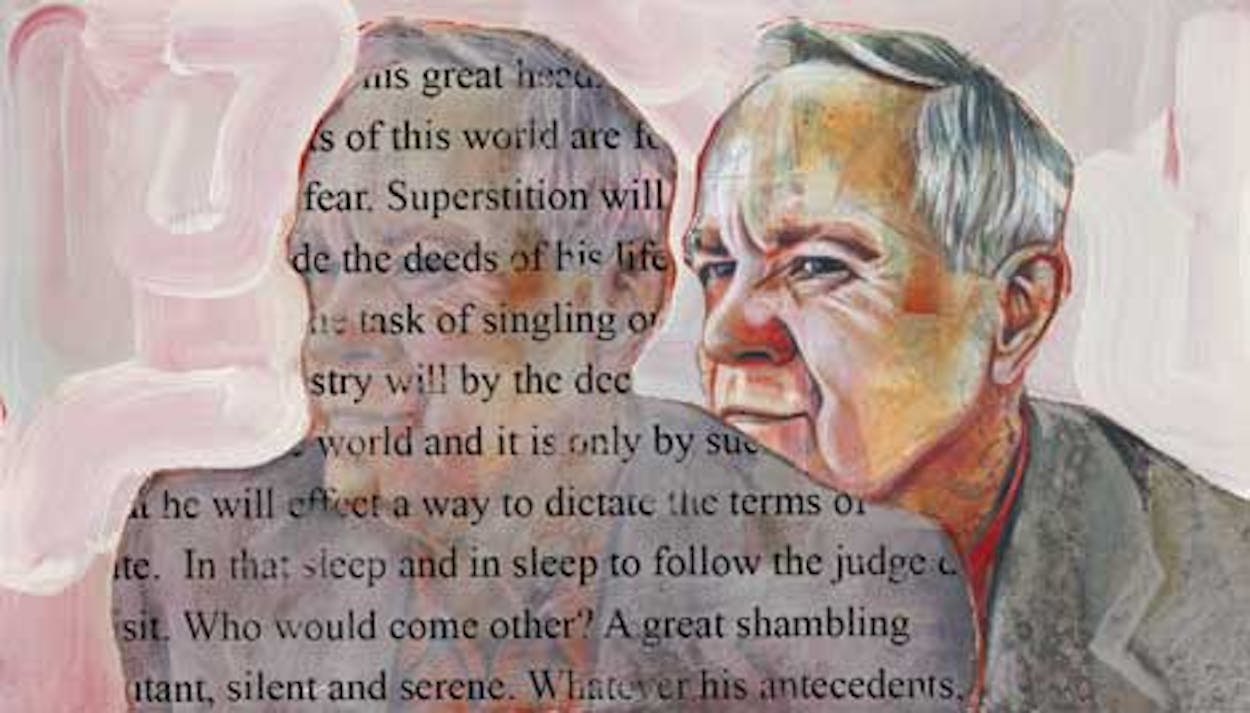

Don’t pretend you don’t know what I’m talking about. I’m talking about your sudden emergence as a visible celebrity, the kind that gets a cutaway shot during the Oscars. Where once your legion of fans could count on your artistic anonymity, now we see your phiz everywhere. For a long while, when I thought of reclusive American writers, three names came instantly to mind: J. D. Salinger, Thomas Pynchon, and Cormac McCarthy. The first managed to stay out of the public eye until a former lover wrote a tell-all memoir, permanently damaging his cult of secrecy. And although the second remains as little known as the Unabomber before he was captured, his work has deteriorated so steadily that no one even cares where he’s hiding anymore.

That left us with you, or it did until a year ago, when you appeared on Oprah. We all know the story. She made The Road one of her book club selections and gave you 48 hours to accept or decline her interview, and you said yes. She put you in a big, overstuffed easy chair and interviewed you till you purred like a kitten. You were cute and cuddly. You giggled, for Christ’s sake! When the horrifying spectacle was over, I half-expected you to crawl into Oprah’s lap and take a nap on her ample breasts.

What did we learn from seeing you that day? That you consider yourself a person with luck. That you don’t care who reads your books. You seemed like any other sentimental, middle-class guy, altogether pleased with how things had turned out. I thought I could hear cash registers spitting out receipts all over America as Oprah’s followers rushed out to get their kicks on Cormac’s Route 666.

Pre-Oprah, the thing I loved about you was that you were a true cipher. You didn’t give readings or do signings or appear in public; you didn’t attend writers’ conferences; you didn’t even take visiting writer positions at universities, the easiest money there is. You were a ghost who wrote like a dream, a Bartleby who preferred not to show himself, and I respected you for it. Authors are the opposite of children: They should be heard and not seen. That’s why Norman Mailer wore out his welcome long before he died. He marched on the Pentagon, made the tabloids for stabbing his second wife, made them again for getting a convicted murderer out of jail who then stabbed an actor to death, ran for mayor of New York, wrote the New York Times complaining about negative reviews, and seemed to be on TV once every week or so. He was like that member of the family who won’t shut up about anything.

Not you, Cormac. You were different. God! Remember how it used to be? In the beginning, you were mostly rumor, some unknown plowman working the burned-over ground not finished off by Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor, some faceless hewer of prose and spiller of blood. In 1976 you moved to Texas, to El Paso, and nine years later, without much fanfare, out popped Blood Meridian, the novel that most critics consider your greatest. Harold Bloom, no slouch he, thinks it belongs right there in the pantheon with Moby Dick and As I Lay Dying. But you didn’t take a victory lap or give us a curtain call. Of course, that could’ve been because the book didn’t sell. It hit the same year as Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove, probably the all-time favorite novel of Texas readers, and James Michener’s solemn, unreadable tome Texas, which was supposed to be—the governor said so—the big book to celebrate the state’s sesquicentennial. Each of those books sold millions of copies, but Blood Meridian sold only about 1,200 in hardback. I guess I wouldn’t have doffed my cap either.

But you stuck to your guns, even as your Border Trilogy started piling up sales in the nineties and your reputation and readership grew. You still never gave any readings, still refused to appear at conferences; you remained out of view, and goddammit, I admired that. I admired it so much that in 2000, at a meeting of a Texas Writers Month committee to select a writer to be honored—a very amateurish promotional idea in the main—I nominated you. Someone asked if you were a “nurturer.” I nearly choked. I told them you had better things to do; you were a writer, not a uniter.

In my class at the University of Texas on Southwestern lit I purveyed such sparse anecdotes as were shared by Cormackians on CormacMcCarthy.com or by other interested parties. I explained how there were two sides to your mysterious person—the tough hombre, who could describe massacres so coldly and eloquently I wanted to see more dead babies hung by their lips on cactus thorns, and the purist, the last high priest of modernism, heir to Joyce’s robes. The only person of my acquaintance who has met you is Tom Staley, the director of the Harry Ransom Center, at the University of Texas. You may recall that what you talked about over dinner was Dubliners. That’s all you would talk about. You quoted sentences from Joyce’s great collection of stories and queried Tom, a Joyce scholar, on what this word meant, what that word meant.

Those were the good years. You just wrote. That was all you needed to do; it is what you were born for.

Why wasn’t it enough?

Before Oprah, you had given exactly one interview—in 1992, to the New York Times. After Oprah, you began to appear regularly in print and on TV, and each public appearance downsized your legend. There you were in Time again, being interviewed alongside the cute little Coen brothers. How depressing. You said you really liked their film Miller’s Crossing. Great. I don’t want to know that. Couldn’t you have mentioned Blood Simple? At least that would have evoked your greatest novel, reminding us that you were, after all, a writer.

And then there was the Rolling Stone article about life at the Santa Fe Institute, the interdisciplinary New Mexico think tank where you’ve been in residence off and on since 1988. Let me tell you something: The rest of us losers are tired of hearing about this place. I don’t care what cutting-edge scientists think. I’m trying to make a living. Leave me alone about quarks and plagues. I’ll deal with them when they show up. The worst part of that article was learning that you bus the food trays after those scintillating lunches. Are you kidding me? Let the goddam scientists bus their own trays.

Also, it was sobering to learn that you haven’t had a drink in thirty years. That’s a long time. So now you’re a teetotaler too?

The coup de grâce, for me, was seeing you at the Oscars. Sure it was only for a microsecond, but there you were, with Jack and Clooney and Jessica Alba. Just another celeb. Beside you, your boy. How heartwarming. The son also rises.

Cormac, please listen to me. Watching your emergence into public celebrity, I’ve rediscovered something I already knew at some level: Most writers fail to impress when they talk about anything other than their writing. They turn out to be no smarter or wiser or better informed than the average joe who listens to talk radio or gets his paranoid politics off the Internet. No one wants to hear about a living author. It’s the dead authors we want to get to know—Hemingway, Plath, Shakespeare. Knowing too much about the living lessens our interest in their words. Not always, but more often than not. To hear Allen Ginsberg read, for example—or even worse, to see him—was quite enough, thank you.

Cormac, it’s not too late! Take my advice. Return to your roots. Crawl back under a rock. If you don’t have one, you could always use that thirty pounds of limestone from the Texas Book Festival.

Your pal,

Don