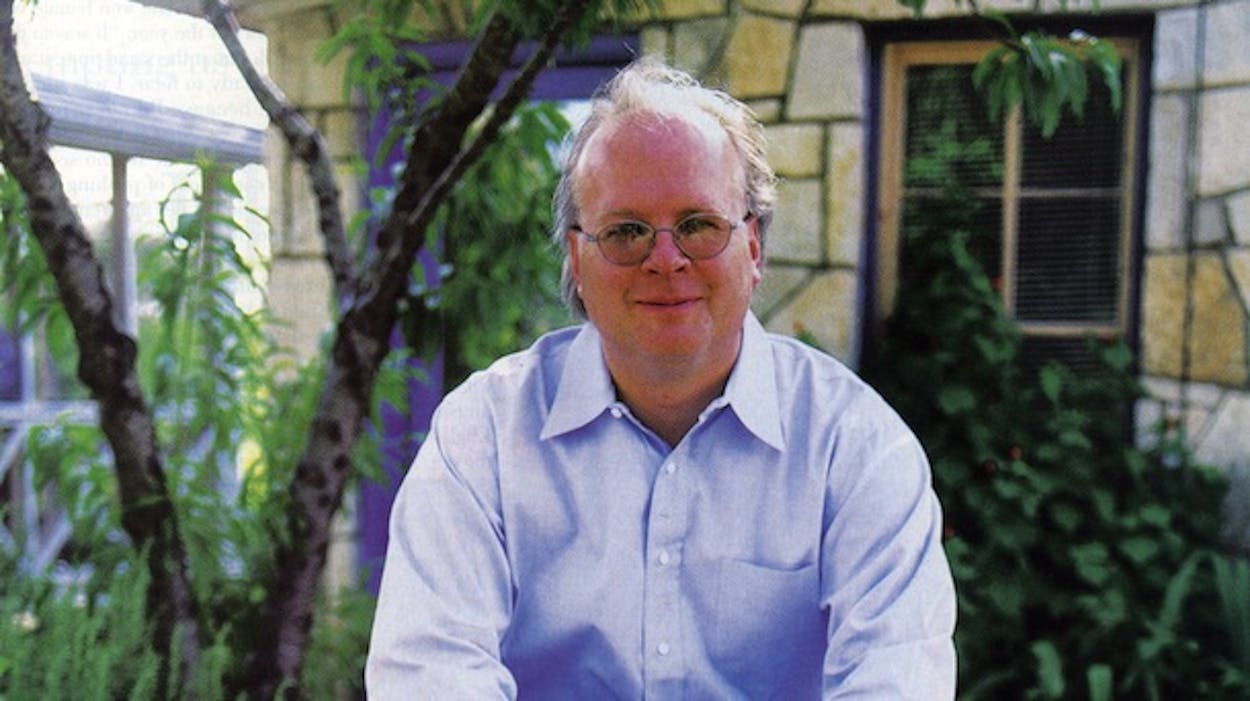

My mental picture of Karl Rove is of him sitting with his back as straight as if he were wearing plywood instead of a shirt, his torso tilted forward with forearms resting on his desk, head erect, hands clasped with fingers interlaced, treating an interview as a quiz for which he is supremely confident that he will have the right answer. As the longtime political director for George W. Bush and the architect of the governor’s presidential strategy, Rove is famous for the discipline he imposes on the campaign, and he is not about to let his own body language be the exception. So it was startling one day this spring to see him end a telephone conversation—he had been barking out instructions about how to deal with yet another stupidity committed by yet another Republican functionary—by slumping over, holding his head by the temples, squeezing his eyes shut.”You can’t get tired now,” I said. “It’s only May.”

“That’s not bad news,” Rove said. “That’s good news. It’s been this intense since January of last year. Seventeen months down, only five to go.”

Now it’s only two to go—two months that will determine the fate not only of Bush but also of Rove. No other noncandidate involved in the presidential campaign has so much at stake. If Bush wins, Rove will stand at the apex of the political consulting profession, a status achieved first by a gent named Machiavelli and most recently by James Carville on the Democratic side and the late Lee Atwater on the Republican side. Rove’s singular achievement was to design and execute a game plan for seeking the presidency that broke the mold. During Texas’ 1999 legislative session, he orchestrated a parade of Republican politicos and fundraisers to Austin that amounted to a draft-Bush movement, crowding every rival off the stage and keeping Bush at home, away from premature national scrutiny. He successfully gambled that the campaign could raise enough money to fund the primary races without the help of federal matching dollars, thereby avoiding the spending restrictions that come with government largesse. After the GOP nomination was safely won, he unleashed a blitzkrieg of issue pronouncements by Bush, catching Al Gore by surprise and propelling the governor into the national convention season with a solid lead.

Once, American politics was run by backroom bosses who knew the secret of how to find good candidates and the votes to elect them. Today, after reform, television, and suburbia have decimated the big-city machines, consultants like Karl Rove have emerged as the new bosses—and are treated as such by the media. National reporters have probed his record and his psyche. He has been described as a “control freak”; he has been accused of running a dirty-tricks school for aspiring Republican operatives in his youth; his upbringing has been combed for clues to his personality; his failure to earn a college degree never escapes mention. Around the state capitol, he is regarded as a Rasputin whose ghostly presence explains every scenario: why a bill was vetoed, or an appointment made, or an issue embraced or rejected by the governor. (In fact, Rove seldom gets deeply involved in legislative business.) He is the elephant—the perfect metaphor for a Republican—and the rest of the political crowd are the blind men of Indostan in John Godfrey Saxe’s poem,each groping for a different part but none seeing the whole. I caught up with Rove during a rare break from the rigors of the campaign over the long Fourth of July holiday. He was staying at River Oaks, a combination bed-and-breakfast and personal retreat overlooking the Guadalupe River between Kerrville and Hunt that he and his wife, Darby, bought four years ago. At first they acquired two cottages, and two years later they added the lodge. “This was built in the thirties by an eccentric from Corpus Christi,” he told me as we toured the property. Rove’s political reputation as a control freak stems from his obsession with details, and the same quality was evident in his conversation about the history of the lodge. Everything seemed to stimulate a story: the oil-pipe fence that had once served as an irrigation system; the dappled limestone floor that had been cut from the riverbed long ago; the high-water point of the 1936 flood, when a piano had washed down the river.It is not surprising that he acquired a B&B; next to politics, his favorite conversational subject is travel. Growing up in Utah, he toured the Southwest with his father, a geologist, before his parents’ marriage ended in divorce. His family was apolitical. Rove was just the opposite; the first book he remembers reading was Great Moments in History. His involvement in Republican politics began in high school, where he served as youth chairman for a U.S. senator from Utah. He went on to join the College Republicans and rose through the ranks of operatives to become the group’s chairman. Later, in what turned out to be a crucial connection for himself and for George W. Bush, he was a special assistant to the elder George Bush at the Republican National Committee during the height of the Watergate scandal. In 1974 he quarterbacked his first campaign, a congressional race in Nebraska. He came to Texas in 1977 to do fundraising for Bush’s 1980 presidential bid. Soon he was the deputy chief of staff to Bill Clements, newly elected as the state’s first Republican governor since Reconstruction.

After two years with Clements, Rove was contemplating going out on his own as a political consultant specializing in direct-mail marketing. Clements brought the issue to a head by asking for Rove’s commitment for the next five years, through what everyone expected would be a successful reelection campaign. Rove replied that he had decided to go out on his own, just as Clements had when he was about Rove’s age. Then Rove asked his boss to be his first client. The answer was yes. Rove handled the mailings for Clements’ 1982 race, but the Texas economy faltered and Clements was upset by Democrat Mark White. Rove was 32 years old, without a major client, and his nonpolitical customers, he says, began to get calls from Democratic operatives who suggested that they might want to find a mail expert who was not associated with an ousted Republican governor.

In the crush of defeat, it was hard to predict that he was the right person at the right place at the right time—the best-known, the best-connected (and nearly the only) Republican consultant in a major state that was still Democratic but tilting, albeit slowly, to the GOP. “I didn’t see it at the time,” concedes Rove, “but it’s clear in retrospect.” With the help of the Reagan White House, Rove picked up Phil Gramm (then a conservative Democrat on the verge of switching parties) as a client. In 1986 he was the head strategist for Clements’ rematch with Mark White. This time a bad economy proved to be White’s undoing and Clements won.

It was about this time that Rove began showing up at the Capitol with a young, personable political neophyte named George W. Bush. Terral Smith, now the legislative director for the governor’s office but then an Austin legislator, recalls Rove escorting Bush to receive briefings on state issues from GOP lawmakers. Rove envisioned Bush as the party’s nominee to succeed Clements as governor in 1990, but when the father won the presidency in 1988, the son’s political career was put on hold. Rove had to be content with two significant downballot victories, Kay Bailey Hutchison as state treasurer and Rick Perry as agriculture commissioner. When President Bush lost his reelection bid in 1992, the way was clear for George W. to challenge Ann Richards in 1994.

When did it first occur to Rove that Bush might be a presidential contender? “Sometime during the ’95 [legislative] session, it dawned on me,” he said. “He was a fabulous candidate, but I didn’t know how he was going to govern. To see him walk onto a stage with such a complicated cast of characters—Bullock, Laney, Democrats in all the major positions—and difficult personalities and win them over was a revelation. The lesson was that leadership sets the tone.”The ability to look into the future and see where politics is headed—as he did by recognizing Bush’s potential, first as a governor and then as a president—is foremost among the three assets that have propelled Rove to the top. More recently, he (and Bush) have tried to get the message out to Republicans that unless the party reaches out to Latinos, it will lose Texas and ultimately America.

Rove’s second strength is breadth. “He is a master of everything,” says Mark McKinnon, who is responsible for the campaign’s media advertising. “Most great political minds can understand strategy, media, and polling, but not all the little parts—budget, scheduling, mail, fundraising. It’s the difference between driving the car and being able to take apart the engine and put it back together when something goes wrong.” In other words, Rove is involved in every aspect of the campaign. (He even uses a mathematical formula based on such factors as the number of electoral votes in a state and who is ahead there to determine where Bush should go and how much time he needs to spend there.) Is he indeed a control freak? “No,” says Rove. “I’m not totally immersed in the details. But there has to be a plan, and you have to follow it. You don’t just discard it on a whim.”

Rove’s third strength is his closeness to the GOP establishment, especially in Texas. This translates into money and credibility for his chosen candidates. With Rove behind him, a candidate is assured of ample funds, and potential opponents in the Texas Republican primary are left with little to no financial support. Every Rove and Bush ally who has gotten on the state Republican ticket represents the thwarted ambitions of unnamed and unknown political hopefuls.

One does not become a highly successful political consultant without stirring up controversy. A lingering question is how the Bush team managed to lose New Hampshire to John McCain by so much. “We fell into focusing on getting out the vote,” Rove says, which doesn’t explain why anyone thought that was the way to win in a state where voters want to meet the candidates personally. The New Hampshire debacle was followed by the flap over Bob Jones University. Rove went on Meet the Press to get the lecture of his life from a visibly angry Warren Rudman, McCain’s campaign chairman, who felt that the Bush campaign had slurred him. “I was scared to death,” Rove remembers, “but I was determined not to leave a charge unanswered. I think I did all right.” His objective was not to look away when the inevitable tongue-lashing came but to look Rudman in the eye—which he did.The charge of dirty tricks has also lingered; it is part of the burden of success in Rove’s chosen profession. He calls the published reports that he ran dirty-tricks seminars “totally inaccurate.” The seminars, he says, featured such benign topics as how to run a recruitment table and how to organize a voter-registration drive. He does confess to one prank: distributing invitations to the opening of a Democratic headquarters in Illinois to skid-row types, complete with notices promising free beer and free food. Rove’s relationships with his fellow Texas consultants in both parties have often been rocky. Several say (though not for the record) that Rove tried to do to them what Rove says that the Democrats once tried to do to him: chase off clients.

Most of the controversy is behind him now. From here on there are only two people who matter, Bush and Gore; only one winner; and such an immense difference between winning and losing. I looked at Rove in the late-afternoon Hill Country sun, and I saw how thin his hair had gotten in the past six months and how far his hairline had receded. “Nothing prepares you for this,” he had told me earlier. If Bush wins, Rove could have all the consulting business he wants; however, he has never been motivated primarily by money. It is easier to picture him serving Bush in a major political post—probably outside the White House, where he would have a freer hand, possibly as chair of the Republican National Committee.

And if Bush loses? Rove is 49 now, and promoting Bush has been the great work of his life. It is hard to envision him going back to managing races for agriculture commissioner. Perhaps he would spend his time trying to get that elusive college degree, writing a book, and reviving the course he taught a few years ago at UT-Austin—the American Political Campaign. He should have plenty of fresh material.