AFTER HALF A YEAR OF AMBIVALENCE about running for president, George W. Bush came back from his 1998 Christmas vacation in Florida with his mind made up to seek the White House. He had talked to his parents, to his wife, to his children—the younger the generation, the more restrained the enthusiasm—but one more person remained whose approval he felt he needed before he made his decision public: his 42-year-old communications director, Karen Hughes. Sitting in his Capitol office, with its portrait of Sam Houston and cabinet stocked with autographed baseballs, he told Hughes of his plans. “If you have any doubts about this,” he said to her, “we need to talk about it right now, because I’m not doing this unless you’re coming with me.”

Hughes did not respond with a perfunctory “Sure, Governor, I’m with you all the way.” Instead, she expressed her doubts about getting involved in a national campaign. She was facing the same issue Bush himself had faced earlier—how to maintain one’s personal life in the face of the seductions of power and the most intense scrutiny and pressure imaginable. “We talked about how all this fit in with my family and my faith,” says Hughes, a soccer (and baseball) mom who is an elder in her Presbyterian church. “Washington’s values are not my values. Everyone you meet is always looking over your shoulder for somebody more important.”

The conversation was intensely personal, touching on their Christian identities, and when it was over, Hughes felt reassured. It is, of course, hard to envision that she ever would have said no to Bush, or that he would not have gone on without her. Even so, the episode captures the essential nature of the Bush candidacy: the deep antipathy of the governor and many of his top advisers to the political system that they hope to take over, the evangelical strain of the campaign that is both religious and political (Bush as savior of the Republican Party), and above all, the indispensable importance of Karen Parfitt Hughes.

Hughes’s job is to oversee the crafting, polishing, and presentation of Bush’s message, which is more than a series of positions on issues; it employs a few consistent themes to tell the public what kind of person and politician he really is. The development of Bush’s national message started on election night last year, when, at Hughes’s urging, he used the phrase “compassionate conservative” several times in his victory speech. In those two words Bush successfully distanced himself from the strident right wing of his party without entirely divorcing himself from it.

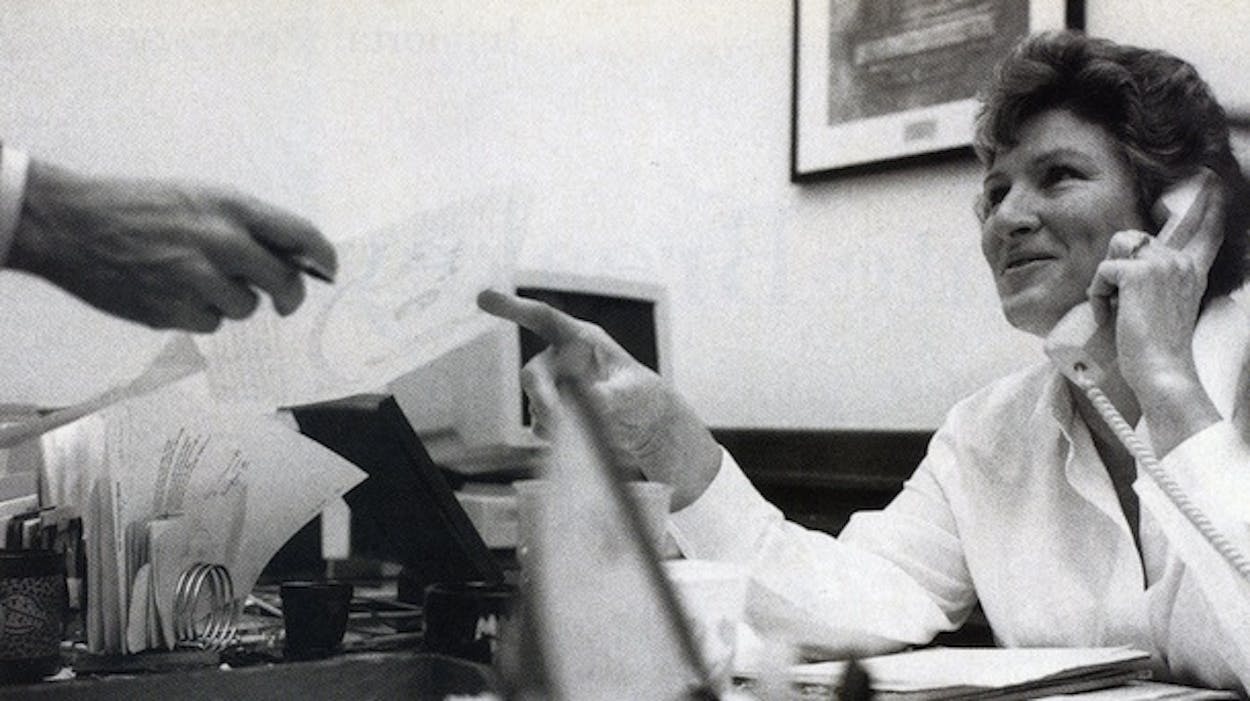

Hughes is one of three longtime Bush hands at the apex of the campaign organization, the others being Karl Rove, whose sphere is politics, and Joe Allbaugh, who runs the business side of the campaign. They constitute a troika of equals; Bush wants no repeat of the czarlike role in his father’s White House played by chief of staff John Sununu, whom he is reputed to have fired. There is an unmistakable culture in this Bush campaign. Its elements are loyalty (far beyond what you would find in a campaign filled with Washington mercenaries); discretion (no leaks to the press); an almost mystical belief in the candidate’s ability to avoid being infected by, and perhaps even to cure, the sickness of Washington; a commitment to focus entirely on the Bush campaign (Rove had to give up his lucrative political consulting business to come on board as a campaign employee); and the absence of competition among the co-equals. And yet Hughes, more than anyone, has Bush’s ear. She is his political alter ego; whether she is giving advice or writing a statement, she has the knack of turning a phrase in a way that appeals to him. In her campaign office at a downtown Austin office building, a few photos of her with Bush rest on a windowsill. One is inscribed, “Without you, it could not happen”; another reads, “By my side—always right.”

“She’s one of the most extraordinary people I’ve ever met,” Bush says. “She’s totally honest; she doesn’t play games with you. She’s got great instincts and judgment.” Bush hands who have watched her in meetings describe her as a kind of irresistible force. She bursts with activity: walks fast, talks faster, reacts instantly, interrupts her own conversation with ironic commentary, and provides her own laugh track. She is tall, just short of six feet, but seems taller and usually wears suits that enhance her air of authority. Her hairdo, which she describes as “low maintenance,” complements the impression of energy; cut short, it has layers that deliberately head off in different directions, reinforcing the sense of energy. When she gets excited during a discussion, she stands up and opens her blue eyes so wide that it seems as if she has grown an inch.

IT SHOULD COME AS NO SURPRISE, then, that her whole life has been one of constant movement. She grew up an Army brat: born in Paris, raised in Pennsylvania, Missouri, Florida, Kentucky, Canada, and Panama, where her father, a major general with the Corps of Engineers, was the last American governor of the Canal Zone. Eventually the family landed in Dallas, and when her father was reassigned again, to Virginia, she stayed behind with a neighbor to complete her last year of high school. Hughes went to Southern Methodist University, expecting to go to law school—“I’ve always been an arguer,” she says—until she took a course in journalism and another in radio-TV newswriting. Her first assignment: Pick an address from a list prepared by the instructor and write about what you find there. She drew the It’ll Do Club. “It was a lonely hearts bar,” says Hughes. “I realized there was a lot of the world I had not seen.”

In 1976 she took a course from Lee Elsesser, then the news director at Channel 5, the Fort Worth—based NBC affiliate, and prevailed on him to give her an internship the next year. At first her main duty was “the meet”—to connect with Dallas-based reporters at the Six Flags exit on the turnpike and speed the tape back to the Fort Worth studio in time for the newscast. She noticed that news was hard to come by on weekends and began suggesting stories that she could cover. When the internship was over, she says, laughing, “everybody wanted me to stay on so that they wouldn’t have to work weekends.” She was hired as a night and weekend reporter, Mondays and Tuesdays off. “It was probably the last time anyone got hired straight out of college to do major-market news,” says Hughes.

The skills Karen Parfitt developed as a reporter are the same ones she makes use of as a Bush adviser: size up a situation quickly, ask the right questions, present information succinctly, and turn a good phrase. She found herself drawn to covering politics, doing stories that ranged from interviewing a young dairy farmer who had just been elected to the Legislature to covering the elder George Bush’s unsuccessful presidential race in 1980. In 1983 she married Dallas attorney Jerry Hughes and acquired an instant family, as he had a ten-year-old daughter. A friend who worked in the Dallas office of then—U.S. senator John Tower asked Hughes if she might want to leave TV for politics. The pay was wrong—“I took a huge cut,” she says—but the timing was right, and she went to work for the Reagan-Bush reelection campaign in Texas. For the next seven years Hughes did a variety of political jobs, sometimes working with a firm, sometimes working out of her home. “It was the grass roots of politics: mayor’s races, bond campaigns, a county judge’s race,” she says. “I wrote campaign brochures, did news releases, and handed out leaflets at the park-and-ride when I was pregnant.”

It was not the fast track to the White House. What changed Hughes’s life was a phone call from state Republican chairman Fred Meyer in 1991. Meyer was looking for someone to be the voice of the party in Austin. At the time, Ann Richards was riding high as governor, Democrats held substantial majorities in both houses of the Legislature, and the only Republicans in statewide offices were agriculture commissioner Rick Perry and treasurer Kay Bailey Hutchison. Meyer offered the job of executive director to Hughes, who had worked in his unsuccessful race for mayor of Dallas in 1987. She and Jerry liked the idea of raising their son, then four, in Austin and decided to move.

Hughes knew how to get attention. “News is contention,” she says. “If you’re willing to criticize, newspeople are willing to let you start a fight.” She developed a style that involved constantly taking the offensive against the Democrats without being offensive. Soon, whenever Richards made any official announcement, reporters called Hughes for a response. A sharp wit was her main weapon. When aides gave Richards a parrot for her sixtieth birthday, Hughes observed that the governor’s staff had grown by 68 percent and said, “I trust they’ve taught it to say, ‘Polly wants a bigger staff.’” Democrats arriving in Fort Worth for their 1994 state convention were greeted by a Hughes stratagem—a billboard, featuring a comment attributed to the Democratic U.S. Senate nominee Richard Fisher while he was still an independent: “The Democratic Party is dead in this state.”

When Bush challenged Richards in 1994, he asked Hughes to join the campaign. Her biggest crisis came two months before the election, when Bush went on a dove hunt and, in full view of reporters, shot a killdeer (pronounced “killdee”), a protected species. The victim’s identity did not become clear until later, but when Hughes and Bush learned what had happened, their reaction was the same: Tell the truth. Bush immediately paid a fine, and the campaign called every reporter who was present to confess. That forthrightness, Hughes believes, limited the damage.

Her development of Bush’s message, throughout his governship and into the campaign, begins with listening to him. Once an interviewer kept pressing the governor to describe his ideology, and Bush, after resisting, finally said, “Call me a conservative with a heart”—which she turned into “compassionate conservative.” She saw how deeply he was affected when, during a visit to a juvenile detention center, one of the boys asked him, “What do you think of me?” That led to “Leave no child behind.” The objective is to have every word that comes out of the campaign—every speech, every press release, every media response—sound like George W. Bush, or at least like Karen Hughes sounding like George W. Bush. That she has mastered the latter art became clear when Al Gore attacked the notion of compassionate conservatism. Hughes fired back a devastating response: “Which is it he has a problem with: compassion or conservative?”

Her own political beliefs are similar to Bush’s. Her conservatism comes from her upbringing in a military family and is rooted in God, family, and country rather than economic dogma or social zeal. In the cultural civil war between urban and rural Republicans, she is more firmly in the urban camp than Bush is, with sympathy for the symbolic importance of hate-crimes laws and a soccer mom’s fear of guns—two issues about which, according to other Bush aides, the governor did not take her advice during the legislative session, to his detriment. (Any mention of their differences makes Hughes very uncomfortable. “I feel free to disagree with him internally,” she says. “We have no external disagreements.”)

SIX MONTHS AFTER BUSH OPENED HIS CAMPAIGN with the formation of an exploratory committee, Hughes has put her doubts behind her. Her concern about keeping her values was eased when she was able to make an early exit from a Bush campaign trip to Iowa so that she could see her son play baseball. There were doubts about Hughes too; skeptics in the national press predicted that she would be too controlling, too protective, too reluctant to grant access—in short, that someone from the provinces wouldn’t know the rules of the game. In the spring the Bush campaign added another spokesperson, Washington veteran David Beckwith, who had worked for Dan Quayle and Kay Bailey Hutchison—but not every word out of his mouth sounded like Bush, and he committed the sin of leaking as well; in July he was gone. By then, so were any questions about whether Karen Hughes is up to the job.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy