This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

In July 2011, more than five thousand miles east of Waco, an assistant designer at the Hermès silk factory, in Lyon, France, unfurled a ninety-by-ninety-centimeter square of the company’s famous silk twill. It was lushly illustrated with the plants and animals of Texas. “This is my favorite scarf,” she said, pointing out the highlights to those of us assembled at the factory for a tour. The scarf, called Faune et Flore du Texas, was designed for the state’s sesquicentennial and had all the romantic detail of a vintage encyclopedia illustration. The assistant designer ran her finger around a ring of prickly pear that encircled an enormous turkey. Her hand brushed over nests of mallards, clusters of raccoons, a rearing mustang, a wild hare, and a stoic-looking Longhorn. More than fifty native animals coexisted within a viny ivy frame that blossomed with firewheels, Texas bindweed, and a particularly lovely downward-facing sunflower.

There are few labels higher on fashion’s Mount Olympus than Hermès. The 175-year-old luxury goods company is known for its handmade handbags, such as the Kelly (which is named after Grace Kelly) and the Birkin (which is named after Jane Birkin, costs between $9,000 and $150,000, and once had a legendary multiple-year waiting list). But perhaps its most coveted and collectible items—and the reason for my visit to the factory—are its $410 silk scarves. Since 1937 the company’s scarf sales have exploded; it is estimated that Hermès now sells one every twenty seconds. Jackie Onassis used an Hermès scarf to hold back her hair, and Princess Grace slung her broken arm in one. Each scarf design is an original commissioned artwork, screened on 450,000 meters’ worth of mulberry moth silkworm thread, and the scarf’s hem is hand-stitched—a process, legend has it, that was once handled by nuns.

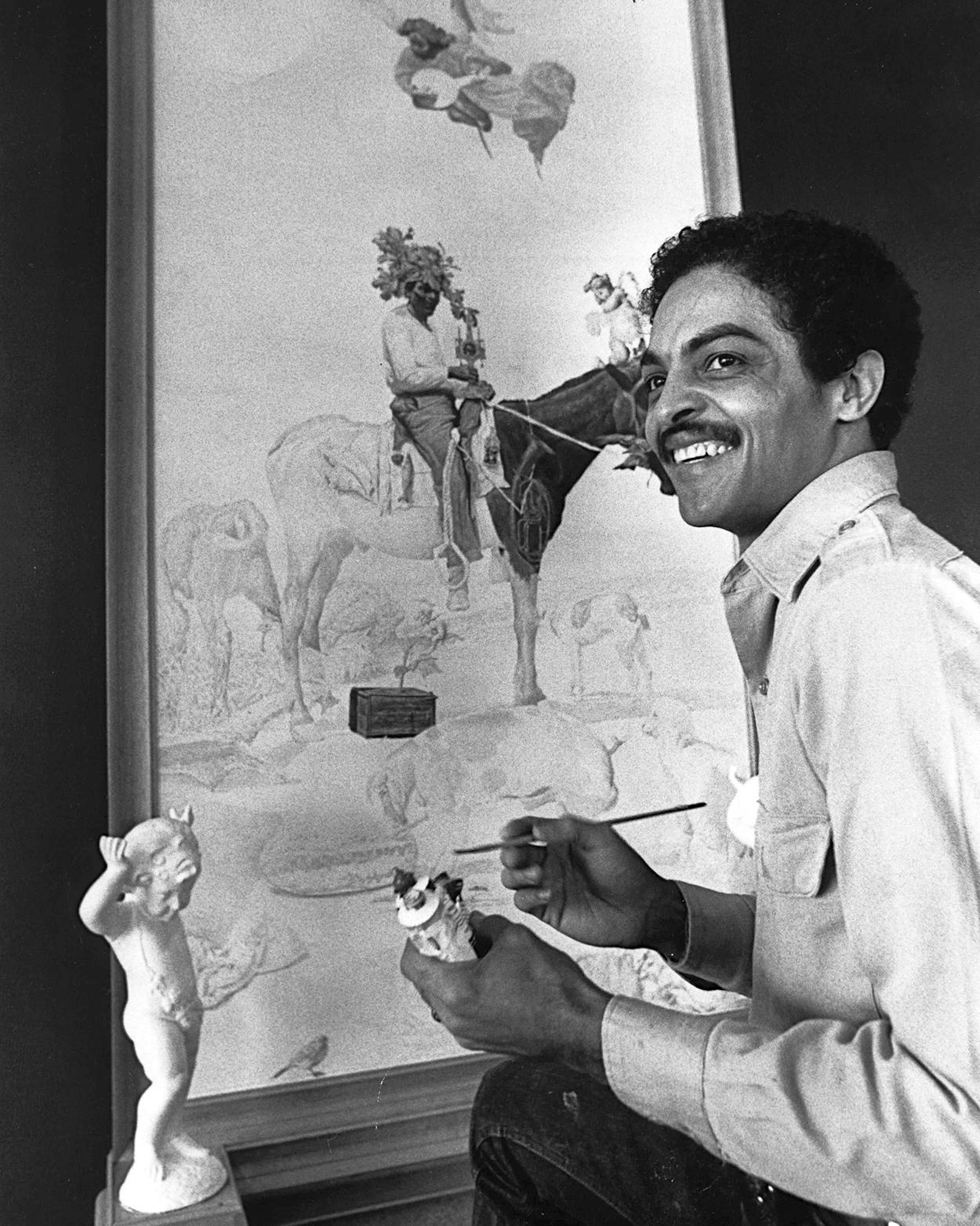

The artist behind Faune et Flore du Texas, said the assistant designer, first caught the attention of Hermès in the eighties. According to company lore, Jean-Louis Dumas, the CEO at the time, loved driving across the United States. On one trip, while visiting Texas, he encountered a painter whose work was so bold but simple, so impressive in its portrayal of animals, that Dumas immediately commissioned a scarf design. That scarf had since been reissued several times and always sold out. The painter’s style was so popular that in the past thirty years, the company had commissioned fifteen more original designs from him. He was the only American artist ever to have designed scarves for Hermès.

Who was this man? I asked the assistant designer. He was very special, she told me. His name was Kermit Oliver, and he was a postal worker in his late sixties who lived in Waco.

On a stormy morning this past April, I went to the rougher part of East Waco in search of Kermit Oliver. In the nine months since I’d first heard his name, I’d learned some more about him. Throughout the seventies, he had been an accomplished though somewhat eccentric painter in Houston, significant enough to have warranted a 2005 retrospective from the Museum of Fine Arts there. Still, very little was written about him—a couple of stories in the Houston papers, a brief 1989 profile in People, and that was about it. I called Kermit’s gallery, Hooks-Epstein, and talked to the owner, Geri Hooks, who gave me Kermit’s phone number (after getting his permission) but warned that he was not going to be easy to contact. She also told me that it was Lawrence Marcus (brother of Stanley Marcus, longtime president of Neiman Marcus) who had orchestrated the partnership between Kermit and Hermès, so I called up Lawrence’s wife, Shelby, who is the aunt of a friend of mine. She confirmed that he would be difficult to get to know (“Very few people can say they are close to Kermit Oliver”) and advised me to let him do the talking. After several calls to Kermit and his wife, Katie, they finally agreed to see me.

I drove south from Dallas under an overcast sky and made my way through Waco to Clifton Street. As I rolled slowly down the potholed road toward his turn-of-the-century white prairie house, two women walking barefoot and drinking beers in the middle of the street tried to wave me off. “Those people are crazy,” one of them said, gesturing toward the house. “They only come out at night.” Few in the neighborhood knew who lived in that white house behind the imposing red-brick wall, and even fewer knew about the art that was created inside. A customer at Jasper’s Barbecue, just down the street, said all he knew was that the house was always lit up at night.

Kermit’s wife met me at the door. She wore dish-washing gloves and an apron decorated with red chile peppers, and her hair was up in a turquoise bandanna. “You know,” she said, “we’re not visiting people.” But she welcomed me in, offered me some orange juice, and led me down the creaky plank floors of a dark, cramped hallway. The walls were covered with art: images of exotic animals, elegant ranch-life pastorals in vibrant colors, biblical allegories. We passed a framed scarf, Kermit’s first for Hermès. Displayed behind dusty glass, it was a portrait of a Pawnee Indian chief on a bright-orange background, surrounded by childlike drawings of galloping horses with flag-toting riders.

Kermit was sitting in the living room, in an armchair covered by a red-and-white quilt. He stood up when I arrived. He was small-framed, with salt-and-pepper hair combed off his forehead. Dressed in loose khakis and an untucked plaid oxford shirt, he gave the impression of a small-town surgeon who’d just gotten off the late shift. His eyeglasses were in his hands, which continuously fidgeted while the rest of him stood still. “Why do you want to talk to me?” he asked.

I stammered something about his story, how interesting it was. He looked skeptical. “Why don’t you tell me what my story is,” he said. I told him what they had said in Lyon, reciting the words almost like the first line of a fable: “There once was a postman who designed scarves for Hermès.”

“Well, it’s never that simple,” he said with a mysterious grin. He led me into his studio, a ten-by-twelve-foot room he called his “monk’s quarters.” It was crammed with artifacts. On a black chest of drawers, next to a shelf of alarm clocks that, in Kermit’s words, “had quit running,” was a macabre scattering of deserted turtle shells; an orange Hermès scarf box, still tied up with the company’s signature brown Bolduc ribbon; and a stack of books on insects and birds. A daybed stood in the corner, and an intricate parquet headboard made of inlaid pinewood hung on the wall above it. One of Kermit’s paintings was set into the center of the headboard—a stunning, circular storybook scene with two monkeys, luscious flowers, and an incongruous smiling cow. There was also a young boy in the painting, Kermit’s son Khristopher. Next to the headboard, there was a framed letter to God. Kristy, his oldest child, had written the note when she was very young. “Oh dear God,” it said at the bottom, in a childish hand, “do you really love me!”

“Painted collages” is how Kermit characterizes his work. Hooks, who has shown Kermit’s art since the late eighties, said the closest description she can think of is “representational.” “Everything represents something,” she said. “He paints everything from his mind, in settings that he thinks are the most appealing.” His paintings have sold at Hooks-Epstein for as much as $70,000 and have been collected by high-wattage Houston patrons like Bobby Cohn and Jack Cato. Of course, he also has a cult following among scarf enthusiasts, especially in Texas. Dumas, one gets the sense, instantly recognized his potential. In 1989 he told People, “When I saw his first design, I said, ‘Kermit, we must not stop here. We must go on.’ ”

So they did. The sixteen scarves that Kermit has designed for Hermès represent three decades of work. Kermit takes six months to a year to design each one, depending on the intricacy of the image and the research required. When he finally arrives at a finished composition, he paints it onto a ninety-by-ninety-centimeter square of watercolor paper, the same size as the scarves, and sends it by FedEx to Hermès in Paris. After the design atelier there approves it, it moves on to the production facility in Lyon, where each color in the painting is traced onto ninety-centimeter-square slides and, in turn, each slide is etched onto a silk screen. That is to say, every color requires its own screen, and because Kermit’s work is both so colorful and so intricate, his scarves are some of the most laborious to print. They are also some of the most beloved. T. Boone Pickens’s wife, Madeleine, and Chase Bank executive Elaine Agather are said to be huge collectors. And while there are thousands of scarves designed by Kermit in the world, they are so treasured that few are ever available for purchase at any given time, and the handful that do make it to eBay sell for $800 or $900. An employee of the Hermès store in Houston told me that when a new design of Kermit’s is announced, it usually sells out before it even hits the floor.

Yet it was hard to tell if this acclaim had affected Kermit’s daily life. His work space was modest, to say the least; for his easel, he had constructed a wooden frame and clipped a piece of heavy cardboard to it. (Reminders were doodled on the surface: “NUBIAN GOAT,” “Write thank yous.”) He told me that his acrylic paints come from Michaels. “I’m a garret artist,” he explained. “I paint very thinly, and it makes the paint last a long time.” The framed scarf I’d passed in the hall and several orange boxes scattered about the house were the only signs of his relationship with Hermès.

I tried to ask about this, but his entire body winced at the mention of fame or money. “That doesn’t interest me,” he said. “Painting is just something I do. I chose not to support my family that way.” Which is why, for the past 28 years, he’s sorted mail at the Waco post office. He works the night shift. His job is processing “hot mail,” the mail that can’t be handled by machines or must be delivered that day. For eight and a half hours—sometimes an hour or two extra if he can score the overtime—Kermit sorts these high-priority messages into a dovecote of cases so that they can be sent off to nearby towns for delivery. When he gets home he paints for a spell, then sleeps for two or three hours. “That’s the schedule we keep,” he said plainly, folding his hands in his lap.

What he paints during those sleepy daylight hours, however, is anything but plain. Kermit’s art exists in an otherworldly universe that reaches far beyond the confines of his dark house in Central Texas—a strange and surreal world where animals, plants, and humans interact in surprising scenes that seem freighted with a mysterious and complex significance. Sometimes his renderings are photo-realistic depictions of religious imagery. Other times they are subtly unusual: a cat sitting on the back of a white cow necklaced with a pomegranate garland.

After a while we headed back to the living room. Kermit sat down in his armchair. He was quiet and disinclined to speak about his art, but since it was literally surrounding him, the subject was hard to avoid. Gesturing toward a painting of a mustachioed black man astride a dull brown mule, he said with his eyes closed, “My work is a reverberation of memories. That’s my father and his mule, Deamon.”

Kermit’s father’s side of the family was brought from St. Louis as slaves in 1840 to work at ranches in South Texas, later settling in Refugio, a small Valley town about seventeen miles from Copano Bay. His father was a cowboy and instilled a strong work ethic in his four sons. “He was as close to a vaquero as you can be. He drove cattle closer to the bay for the winter.” Of the four brothers, Kermit was, he says, “the hoodlum, the bad child.” He stole BBs for a BB gun he didn’t even have. But he was frequently at church and developed a deep understanding of the Bible and a strong faith. He also learned a lot about God’s creatures. “I was constantly around sheep, goats, cows, horses, chickens—the elements I use.” According to an essay by the African American art expert Alvia J. Wardlaw, Kermit was deeply impressed by the animal slaughter he witnessed on the farm, later portraying it in his work “as a symbol of the crucifixion.”

Refugio was a melodic blend of black, Hispanic, and white cultures. “It’s very convoluted,” he said of his own racial background. (His great-grandmother was three quarters Irish, and his mother’s father was German American.) After high school, Kermit, who was skinny with long curly locks and light skin, went to Texas Southern University. But he found that he felt out of place there, in the politically charged atmosphere of a black university during the sixties. “It was hard for me to get into the civil rights movement,” he said. “I thought it was an urban thing. There wasn’t that conflict back home,” he said in his halting whisper.

Kermit majored in fine art and education. At TSU he met Katie, another art student. “He and Katie made a striking couple,” said a fellow TSU alum, Robert Jones, who today is a Houston attorney. “He rode an English bicycle. Katie wore artsy clothes.” (She also read Women’s Wear Daily.) Throughout college, Kermit was nurtured by a popular professor, John Biggers, a legendary mentor to many of the state’s homegrown black artists, and his junior year, he attended an artist seminar class conducted by Willem de Kooning’s wife, Elaine de Kooning, at Rice University. But Kermit was uncertain whether he could be an artist; his teachers had essentially told him that that door was closed. He assumed that if you were black, you weren’t going to create anything that would be wanted by a gallery. Black art students were there to be made into art teachers. And they were told not to be disappointed by this. Kermit remembers that the message was “You’re going to give other people a means to express themselves.”

After graduation Kermit taught at TSU, but only for three semesters, because in 1970 the most remarkable thing happened: Ben DuBose gave him a solo show at his namesake gallery in River Oaks. This made Kermit the first black man represented by a major Houston gallery, and soon he was one of DuBose’s most successful artists. His openings were events. More than a thousand folks turned out for them, the walls covered in “sold” dots by ten o’clock at night. Kermit became a favorite of the powerful Houston Post art critic Eleanor Freed, and his phone rang off the hook with Houston socialites wanting their portraits painted. Kermit Oliver was a smash.

But he couldn’t enjoy it. Despite appearing on the Post’s society page dressed in natty suits, despite the high-dollar sales and the insider access, Kermit never stopped feeling like an outsider, even on his own opening nights. “We would approach the gallery and stand on the other side of the plate glass windows until someone would come out to get us or motion for us to come inside,” he said. Kermit found the openings draining. “People want you to explain the painting they purchased,” he said. He and Katie were often the only blacks in the room. This was particularly true at fancy “meet the artist” dinners held after the openings. “One man, a decorator, said, ‘How do you get your hair like that? It’s like a head full of black pearls,’ ” Kermit recounted. “That’s what it was like.”

Kermit was, however, canny enough to pick the right friends. Shelby Sanders Stroope, the director of public relations for the DuBose Gallery in the seventies, was so charmed by Kermit’s personal panache and talent that she began to promote him on her own. “One of Kermit’s trademarks as an artist was that he often made his own frames,” she said. Frequently he created them even before he knew what he was painting. They were “intricate, carved wood borders, sometimes with wooden insects creeping at the corners,” said Stroope. “No other artist did that.”

At that time, Stroope was recently separated but had begun dating Lawrence Marcus, the executive vice president of Neiman Marcus. Kermit soon met Lawrence as well. One day, while delivering a number of paintings to the gallery for an upcoming show, he presented Shelby with one that was all wrapped up and told her not to open it until she got home. She rushed home to tear open a portrait of Lawrence next to a mannequin’s hand bound in a pink ribbon. On the back, in felt-tip marker, Kermit had scribbled, “He who wears a ring on his finger is bound for life. He who slips his ring on his middle finger is soon to be married. He who wears it on his index finger leaves his loved one at the door. He who puts it on his little finger is certain of pleasing. He who wears his rings on all his fingers, this is the white hand to behold. For Shelby and Lawrence, happiness. Kermit and Katie, 1978.”

Shelby was embarrassed. She immediately called Kermit and said, “Kermit! I’m not even divorced yet! Lawrence is not going to ask me to marry him.” Kermit just said, “He will.” Indeed, Shelby and Lawrence were married later that year. “Kermit’s a bit of a mystic,” Shelby insisted. In another portrait Kermit did, of Shelby’s two-year-old granddaughter and her toys and pets, Kermit painted the family dog exiting the frame. “My daughter was very upset,” Shelby said. “When I asked Kermit about it, he told me, ‘That dog is not well.’ And, well, a few weeks later the dog was dead.”

Given his premonitions, one wonders if he knew what was coming next. In 1980 Hermès asked Lawrence for help in locating an American painter to design a Southwestern-themed scarf. Lawrence immediately thought of Kermit’s portrait of him. It had hung outside his bedroom for two years, where he passed it daily, noting its composition and its frame. “Since Kermit either begins or ends his work with the frame being part of the design,” Lawrence said, “I realized he was thinking in squares.” Lawrence told Hermès about Kermit, and when Xavier Guerrand-Hermès, the president of U.S. operations at the time, visited Texas, he met Kermit at his home in Houston, where he was captivated by Kermit’s headboard painting. At a follow-up meeting at the Hermès in-shop boutique at Neiman Marcus, Guerrand-Hermès asked Kermit to select one of three subjects to paint: something Southwestern, the history of Neiman Marcus, or a Native American theme. Kermit chose the third option, and his resulting Pawnee chief scarf was enough of a success to warrant another assignment. Kermit’s career as an Hermès artist had begun.

And yet it was at this same time that he essentially retreated from the art world. He had a falling-out with Stanley McDonald, who inherited the DuBose Gallery when Ben DuBose died. In 1984 Kermit and Katie moved from Houston to Waco to care for Katie’s ailing grandmother at Katie’s childhood home. For seven years Kermit was not represented by a gallery and painted very little. He had started working as a processor at a Houston post office in 1978, and he was able to transfer to Waco. He assumed the life of a postal worker. There was no more walking to museums, no getting lost in a room of Renaissance paintings. The only works he was known to do were commissions arranged by art consultants, as well as the scarf designs. Other than that, he just sorted mail.

Four months after I visited Kermit in Waco, I spent an afternoon with Lawrence and Shelby Marcus at their Highland Park home. We spoke for several hours over cranberry juice and gingersnaps. I told them that despite the fact that Kermit had been warm and generous with his time, and unexpectedly forthcoming, he remained almost entirely opaque to me. (He also refused to be photographed for this story.) Shelby wasn’t surprised. She said that one of the last times she’d seen Kermit socially was about 25 years ago, at the opening of the Hermès store in Highland Park. There was to be a dinner in his honor at the Marcuses’ home following the event, with Hermès executives and VIP customers. Everyone wanted to meet the artist, and Kermit had promised to attend. But he never showed. “We weren’t offended,” Shelby said. “We knew Kermit.” He later mailed an apology letting Shelby and Lawrence know he’d had to get back to Waco for his shift at the post office. Before I left the Marcus home, Shelby asked me if I’d spoken to Kermit about his son Khristian. “When you understand what happened to Khristian,” she told me, “you will understand Kermit.”

The story is tragic. Kermit was understandably reticent on the subject, but I managed to learn most of the details from Katie; their daughter, Kristy; Geri Hooks; one of Khristian’s lawyers, Winston Cochran; and various newspaper reports. Khristian was Katie and Kermit’s youngest child. He was seven years old when the family moved from Houston to Waco. He didn’t look like his brother, Khristopher, who was three years older than him, or like his sister, Kristy, who was twelve years older. He had blond hair and blue eyes. As a child, he loved to draw, like Kermit, and he was steeped in religion. When the winos and druggies outside the house made too much noise, he went out and preached the 23rd Psalm to them. As Khristian got older, he started eating dinner in his room. He shaved off all his hair and listened to Benedictine monks chanting and visualized being one of them. During his junior year, he fell in love with a girl and got engaged. But her parents disapproved and sent her away. Brokenhearted, Khristian transferred to public school for his senior year, fell in with the wrong crowd, and began fighting with his parents and referring to the home with the red-brick wall around it as his prison.

He also started going out with another girl, named Sonya Reed, and on a March night in 1998, they ended up in Nacogdoches County, smoking weed in a truck with two brothers, Bernardo and Lonnie Rubalcana. At some point, they decided to break into a house that looked unoccupied. Khristian was carrying a .38 caliber pistol. Sonya, who was three months pregnant, and Bernardo stayed in the truck, with instructions to honk the horn if someone came home. Khristian broke a window and made a lot of noise to make sure the house was vacant, which it was. But when the owner, Joe Collins, came home, there was no honk to alert Khristian and Lonnie, so the 64-year-old caught the boys off guard. He was carrying a rifle, and the situation quickly turned deadly. Collins shot Lonnie, and Khristian shot Collins five times. Then Khristian is alleged to have beaten Collins on the head with the butt of his rifle. He escaped out the front door, dragging Lonnie with him.

Khristian and Sonya took off for Waco, while Bernardo took Lonnie to a nearby hospital. It didn’t take long for the police to put it all together, and after a search of Kermit’s house, Khristian and Sonya were found hiding out in a Waco motel. Khristian was charged with killing Collins, and the trial was held in Nacogdoches. The Olivers drove the four hours each way every day. They hired a top defense attorney, Mike DeGeurin. The fees for the trial and appeals alone cost nearly half a million dollars.

Though Kermit had maintained only a long-distance relationship with the art world, it rallied to his side. Geri Hooks sent out letters announcing that Kermit would paint portraits at “greatly reduced prices,” and she published two editions of Kermit’s prints and two editions of Katie’s prints to raise money for attorneys’ fees. Shelby called a summit in Dallas around the Marcuses’ 24-person dining room table. A deal was struck with representatives from Hermès. They ordered fifteen additional color variations on existing scarves from Kermit for half a million dollars. Hermès would keep all the rights, allowing for Kermit’s work to appear on everything from boxer shorts to ashtrays. About the deal, Kermit said, “You have to trust people.”

Bernardo and Lonnie Rubalcana, who took plea bargains and testified for the prosecution, got 5 and 10 years in prison, respectively. Sonya was sentenced to 99 years. Khristian was sentenced to death.

It is difficult to know the suffering that Kermit and Katie endured over the next ten years. They visited their son once a week at the Terrell Unit (later renamed the Polunsky Unit), outside Huntsville. Khristian and Kermit exchanged work. Khristian painted watercolors—oftentimes, like his father, depicting animals. Between visits, Kermit would send Khristian photos of his own paintings, challenging his son to replicate the composition. During these periods, Khristian also illustrated children’s books for the daughter he’d had with Sonya—using whatever rudimentary art supplies were available on death row. Finally, on November 5, 2009, in front of his family and the family of Joe Collins, Khristian was executed by lethal injection. As the poison flowed into his veins, he began reciting the 23rd Psalm. He got as far as “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow . . .”

The terrible reality was hard for the family to accept. “We watched him take his last breath,” Kristy told me. “But when we were at the funeral, [my mom] thought it was somebody else in the casket. Or that his body was made of porcelain.” Kristy works as a mail carrier in Houston. She talks to Katie and Kermit on the phone every day. “My mother thinks Khristian is still alive,” she said. “She’ll ask me if I’ve talked to him. She’ll tell me to tell him to come home. She’s told people that Khristian’s in Paris.” Kristy believes that her mother, who is obsessed with Kermit’s scarves, has placed him there in her mind because of a vacation they took to the Hermès factory in 1988, a trip that remains one of the family’s happiest memories.

Kristy told me that Khristian’s execution has changed Kermit’s work. She mentioned her father’s painting that hangs in Houston’s Trinity Episcopal Church, titled Resurrection. It’s a nine-by-six-foot altarpiece, painted in violent red hues, depicting Christ rising from his tomb, except that Kermit used Khristian as the model for Christ. In the electrifying and chaotic piece, white fabric billows up as Christ steps on a snake. An apocalyptic mushroom cloud explodes behind him. Christ’s head is crowned with white lilies. “It’s like a bomb blowing up and blood in the sky,” Kristy said. “What was going on in his head? I can’t imagine losing a child. He’s a changed man. What happened to Khristian pushed Papa further into his own work and his own mind.”

It was 107 degrees in Waco when I pulled into Kermit’s driveway this past August. He’d agreed to see me one more time. He was outside cutting down sunflowers. They’d grown too tall beside his studio window, and he said they were scraping against a railing and making too much noise. As he whacked the stalks, he threw them in the trash can.

We entered the house and walked through the serpentine halls to the studio in the back. A box fan blew, fluttering the frayed stacks of National Geographic and Texas Parks and Wildlife magazines by the window. Next to some crinkled paint tubes, a gold-colored clock ran 28 minutes fast. “That gives me some time,” Kermit said.

He sat down in front of a large, unfinished painting. At the center of the paper was a corpse covered in a white sheet, with a single pale foot showing. A Virgin Mary figure, who looked a lot like Katie, held the body, while a young blond girl offered the corpse a red poppy. Next to these figures stood a shrouded woman holding a meadowlark; to my eye, she resembled Kermit. (“Well, artists are self-referential whether they want to be or not, right?” Kermit said.) In the background stood Rick Perry, dressed in a crimson Western shirt and a bolo tie, clutching some sunflowers. Scattered about were also a few of Kermit’s trademark animals: a dog that resembled a pit bull stared at the girl, a moth perched on Perry’s sleeve, and a heron appeared to fly into the frame.

I asked if the body was Khristian’s. Yes, Kermit said. This painting represented “the betrayal, as well as the redemption and the Resurrection.” The girl was Khristian’s daughter, who is now twelve years old and lives primarily with her maternal aunt and uncle. The poppy she held was a symbol of sleep and death. The dog stood for “sin-eating”; the heron represented rebirth.

My presence that day seemed to make Kermit angry. He was more verbose; his eyes were open. I was an intruder, asking for explanations he didn’t want to give. He told me that the figure of Perry was meant to represent “the Western ethos, the cowboy ethos.” The sunflowers in Perry’s hands stood for Khristian’s life being cut short. “My son was executed, and the governor was out politicizing,” Kermit said, referring to Perry’s reelection campaign the year of Khristian’s death. He looked out the window where his own sunflowers once swayed.

“What was the purpose of everything that’s happened?” Kermit said, his voice rising. “Some ancient writings feel that the God of this world is not the God that created it.” He closed his eyes and paused. “Let me put it this way: Do you think God created tornadoes and hurricanes and tsunamis and everything as a punishment for people? Or is that just coincidence?” Kermit stopped, suddenly reticent. He sat still, but his long and weathered hands twisted and turned in his lap. He wrung them out like a dishrag. “Life is chaos,” he said. He looked out the window. “Some of us survive it. Some of us don’t.”

He turned back to his painting, his lined eyes seeming to narrow on Khristian’s foot extending from the sheet. “If God is love, why is he going to destroy his creations?”

I looked around the room, that tiny cell where Kermit spent all his free hours. Geri Hooks had said that she suspected Kermit was only ever truly at peace when he was painting. During the trial she had asked Kermit if he was okay. “ My needs are very simple,” Kermit had told her. “Give me a room with good northern light, my books, my art supplies, and a bed and stick some food under the door, and I’m the happiest man in the world.”

He stood up. It was time to prepare for his shift at the post office and time for me to go. Kermit walked me back through the quiet halls. I passed the Pawnee chief pressed beneath glass, the painting of his father, and a portrait of Khristian next to an Irish cross. Outside in the driveway, under the late-day sun, Kermit squinted at me and shook my hand. When he cut a few more sunflowers and handed them to me, I knew I would not be seeing him again.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Art

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Fashion

- Waco

- Houston