This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Lined up on my desk, like a row of high-fashion magazines or brochures for condominiums in Palm Springs, are thirty slender volumes brimming with compound Latinate sentences. I have been reading these compound sentences for two weeks now, navigating the shoals of garbled syntax and the reefs of technical obscurity like Ahab stalking the white whale. It hasn’t been easy going. For these are the annual reports of the biggest oil companies in the USA, and they yield up information only in fragments, and then only grudgingly.

I began this marathon of exegesis with the instinctive feeling that somewhere in all this verbiage—waiting for me like an oil field in the depths of the Baltimore Canyon—were riches undreamed of. Like virtually every citizen of the republic, I have been assaulted almost daily with impassioned attacks on the oil industry and equally self-righteous defenses. Are the oil companies getting rich at the expense of the rest of us? At the conclusion of a New York Times editorial, I tend to believe they are, but after hearing the well-reasoned manifesto of an oil executive addressing the International Trade Conference in Houston, I’m inclined to say oil companies need all the help they can get. The statistics used are the same on both sides, and yet on every major issue—How much oil is left? How feasible are synthetics? Just how incompetent is the Department of Energy? Is Jimmy Carter hindering the search for energy?—any kind of reasoned analysis breaks down into polemics.

That is what the oil industry has been telling us all along, of course. To them the American mass media constitute little more than a cauldron of superstitious folk wisdom. The networks have an antibusiness bias, the newspapers ridicule the companies’ quarterly profit reports, and the Congress—shamelessly fearful of bucking the tide of misinformation—capitulates by invoking the strong arm of punitive taxation. No wonder most of these companies have retreated into a protective cocoon of high-minded press releases and occasional expert testimony before predatory committees of the Senate.

But at least once a year the oil companies vault into the ring for one good round of sparring against the onslaught of misinformation. And most of them lavish on an annual report the kind of care and attention usually reserved for meetings with the outside directors or presentations for the Council on Foreign Relations. An oil company report is more than facts and figures, charts and graphs. Judging by the heft, texture, paper quality, artwork, color photography, and graphic design of this genre, these documents are intended to be no less than works of art. And so they should be. After all, this is the only coherent picture we have of life beyond the boardroom door. If the officers and directors of the Gulf Oil Corporation want to explain the new thermal regenerative cracking process used for the manufacture of olefins in a plant at Cedar Bayou, I figure the least we can do is listen. If the elusive goal of energy independence is essentially a technical issue—and the oilmen maintain it is—then this is where we should go to resolve it. Perhaps, like the detective in Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Purloined Letter,” we will find the solution to the energy mystery in the most obvious of all places.

Here, then, is the world as seen from the other end of the gasoline hose.

How Big Is Big?

Few corporations are coy about promoting cash flow figures, but then few corporations are larger than most nations. For example, Exxon Corporation’s 1979 revenues of $84.8 billion are equal to the gross national product of Switzerland. Mobil is only the size of Austria; Texaco, roughly the size of Norway; Standard Oil of California, a few billion larger than Greece; and tiny Gulf, the size of a mere Malaysia.

It was not easy, by the way, to find a precise figure for Exxon’s revenues, since it doesn’t appear in the “Milestones” on page 1 or in the letter to the shareholders. By carefully scrutinizing a column of figures in the “Financial Highlights” section on page 4, I finally located the magic word “revenue.” Since Exxon is the only oil company that did not advertise its revenues, you may be unaware of just how big the company is. Think of it this way: Exxon takes in $10 million every hour. It is also probably the world’s largest taxpayer, having paid out $23.1 billion last year in more than a hundred countries. And its 1979 profits of $4.3 billion represented an increase of 55 per cent over 1978.

The pictures of Clifton C. Garvin, Jr., the chairman, and Howard C. Kauffmann, the president, on pages 2 and 3 of the report emphasize the firm jaws and furrowed brows of men who supposedly don’t have time for humor. This is hardly the case. Their joint letter to shareholders begins, “Exxon’s earnings in 1979 were up sharply . . .” “Up sharply” is their droll way of saying they made more money in a single year than any corporation in the history of American industry.

What, Me Worry?

Mobil Corporation edged out five other contenders for the best explanation of why its profits are not very good. Since annual reports are ostensibly written for the benefit of stockholders, this is a commendable display of candor. After all, stockholders want to hear that profits were better than ever. Therein lies the genius of Mobil’s achievement. For its profits were better than ever—a total of $2 billion after taxes—but Mobil came up with four reasons, supported by statistics and charts, why they were worse than they looked.

So Mobil’s profits were up 78 per cent? Doesn’t mean a thing. First look at the graphic illustration on page 7, showing how a dollar of Mobil revenue is divided among suppliers, government tax collectors, employees, and finally—that lone penny down at the bottom—its shareholders. Then turn to page 29, under the heading “Earnings in Perspective,” and note that Mobil earned only 4.4 cents on each gallon of product sold. Who’s going to begrudge Mobil a few pennies? Those two figures—the shareholder’s penny and Mobil’s 4.4 cents—collectively represent a mere 252 billion cents.

Next, says Mobil, we must look not at profits but at “profitability,” otherwise known as return on investment. Here we are on more familiar turf. After the third-quarter profit reports of 1979 produced figures that Senator Henry Jackson labeled “obscene,” every oil company in America issued a press release noting that its return on investment was lower than the average for American industry and in some cases lower than the rate of inflation. Return on investment, put simply, is the number of cents earned by the company for every dollar invested, and the manufacturing industry average is 16.7 per cent. Last year Mobil’s return on investment was 20.5 per cent. But don’t pay any attention to that. Instead, look at the figures for the past six years, as Mobil instructs us to do, and you will see that Mobil’s return has fallen below the industry average in three of those years.

The third Mobil argument calls our attention to the massive sums that the company is reinvesting each year. The key phrase here is “capital and exploration expenditures.” Whereas the company earned only $2 billion in profit last year, it invested $3.8 billion. Presumably this proves that Mobil is out there drilling thousands of holes, looking for oil all over the globe. But the only figure that would tell us that for sure—amount spent on wildcat wells—is nowhere to be found in “Earnings in Perspective.” That was wise. For you can find that number in a column of figures at the back of the report: it is $499 million—25 per cent of the profit figure and 13 per cent of total capital investment. The other 87 per cent was spent on working the oil fields that have already been proved and developing such projects as the Mei Foo condominiums in Hong Kong and a new line of microwave ovens at Montgomery Ward.

Finally, no explanation of disappointing record profits would be complete without a reference to inflation. Mobil devotes an entire page to the subject and adjusts its earnings to the consumer price index by using constant 1967 dollars. We are invited to look at price increases for six years—since 1974—and to notice that what appear to be profit rises of 90 per cent amount to only 29 per cent when adjusted for inflation. It might not occur to us to ask two questions that aren’t answered by Mobil. The first: why does this earnings report begin in 1974? The answer might be that the Arab oil embargo occurred in 1973, doubling gasoline prices and making 1974 the most profitable year in the history of the oil industry. Compared to 1974, 1979 doesn’t look bad. The second: how much did profits increase last year in constant 1967 dollars? The answer might be 59.5 per cent.

No one else is quite as creative as Mobil in accounting for profits, but several of the runners-up deserve mention. Standard Oil of Ohio had a 164 per cent increase in profits last year. But 1979 was the first year that Sohio’s huge oil reserves in Alaska really started to flow, after the company had spent ten years pumping money into that state with no appreciable return (a mere 6.9 per cent since 1970). The $1.2 billion profit in 1979 amounted to a whole decade of earnings achieved all at once. So defending these profits was a simple task for chairman Alton W. Whitehouse, Jr., and president Joseph D. Harnett, who merely pointed out the right figures.

The Sun Company (profits up 69 per cent) went to some trouble to squelch the rumors of “excessive profits.” Pictured on page 9 are four stockholders—two male and two female—seated around a cozy hearth with chairman and president Theodore A. Burtis. These stockholders have a lot of tough questions for the chief executive. “Are Sun’s profits excessive?” asks Anne M. Reilly of Haverford, Pennsylvania. “No,” replies Burtis with conviction, “our profits are not excessive. Not by any measure.” And then he launches into an explanation of Sun’s average return on investment—about 20 per cent, which he finds “eminently reasonable, considering the risks of the energy business.” Reilly is smiling in the picture, and she doesn’t ask a follow-up question.

Texaco’s modest profit increase of 106 per cent would sound equally reasonable if you were to read “Texaco in Perspective,” a two-page question-and-answer dialogue between an anonymous interrogator and an omniscient respondent. Texaco’s perspective is, oddly enough, similar to Mobil’s perspective, with a slightly heavier emphasis on return on investment (17.7 per cent) and a conspicuous allusion to Texaco’s tax burden ($6.9 billion).

Glossing Over Alleged Billion-Dollar Crime

Exxon devotes one paragraph on page 34 to the Department of Energy’s claim that the company has overcharged its customers from 1973 to the present in amounts that total at least $1.3 billion. The pricing regulations, says Exxon, are “vague and ambiguous.”

The Minority Opinion

Exxon displays not one but two Indians on page 23 of its annual report—a Pueblo woman studying economics at the University of New Mexico (thanks to Exxon’s contribution to scholarship funds) and an Oneida identified as the chairman of the scholarship committee of Arrow, Inc. Arrow is one of several minority foundations receiving grants from Exxon, despite the fact that only 8 per cent of Exxon’s managers and professional employees are members of minority groups. (No figures were given for percentage of Exxon American Indians.)

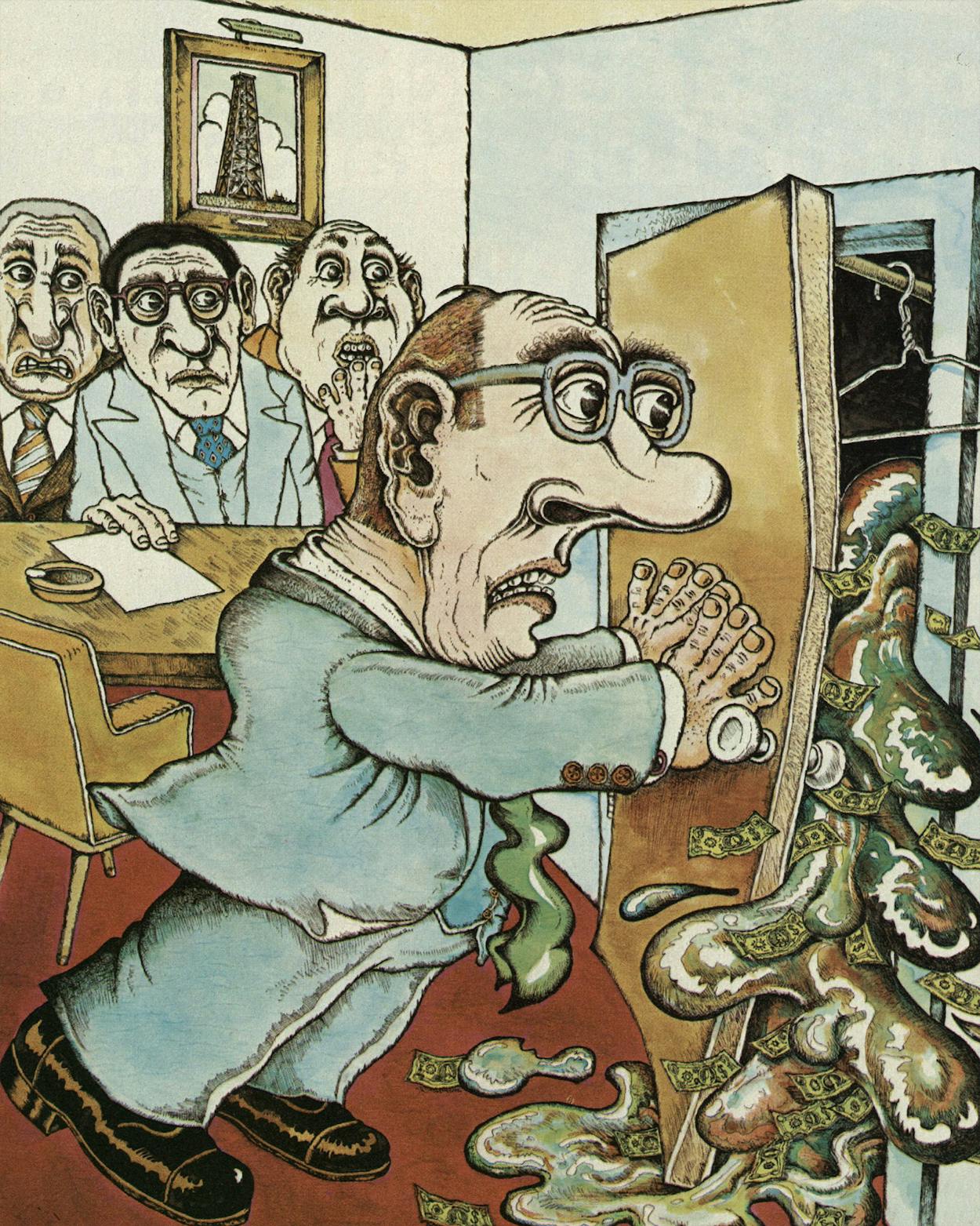

Pictures of smiling minorities are de rigueur in oil company reports, second only to heavy equipment in popularity. The same goes for women. Judging by the Sun Company’s cover, a collage of twenty happy faces in the style of a 1960 social studies textbook, the business is run entirely by women, blacks, Mexican Americans, Chinese Americans, and blue-collar workers with sun-creased faces and hard hats. Contrast that picture with the inevitable back-of-the-book portrait of the board of directors, usually seated around a conference table at least twenty feet long, and you may notice a preponderance of middle-aged Anglo-Saxon males. Still, there are notable exceptions. Eight companies have women serving on their boards, and Phillips Petroleum has two.

In truth, the presence or absence of large numbers of minorities on the payroll matters much less in the oil industry than it does in most American businesses. General Motors, for example, employed 853,000 people last year, whereas Exxon, a company worth $17 billion more, employed only a fifth of that number. Since energy is a capital-intensive—as opposed to labor-intensive—business, the more important criterion is how much cash a company pumps into the minority community through purchases of raw materials or through joint ventures. Only six corporations made a nod in this direction. The most notable were Standard Oil of Indiana, which did business with 1100 minority vendors last year (spending $75.4 million), and Standard Oil of Ohio, which invited several corporations owned by Eskimos to participate in Standard’s bidding for offshore leases in the Beaufort Sea. The other companies with “buy minority” plans were Texaco, Shell, Union Oil of California, and Atlantic Richfield.

How Pistachio Nuts Fight OPEC

A year ago Jimmy Carter coined the phrase “windfall profits” with a caustic reference to oil companies that appeared more interested in “department stores and circuses” than in finding oil. The sarcasm was not lost on Mobil, which had purchased Montgomery Ward, or Gulf, which had considered buying the Ringling Bros, and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Carter’s implication was that any company with spare cash for ladies’ undergarments or the salaries of lion tamers didn’t have its heart in the job at hand.

Once again, the president was sorely misinformed. For had he been reading his annual reports, he would have learned that oil companies as we know them are no more. Instead, the operative term is “diversified energy concern,” with an emphasis on the word “diversified.” The theory is that a plant making widgets in Akron contributes just as much to energy independence as a million-barrel refinery in Port Arthur. When the demand for gasoline declines, as it did during the notorious “gas glut” of late 1978, the widget factory can continue to pump those profits into expensive drilling projects going on around the world. Hence, anything that makes money is a blow to the OPEC cartel.

It should be no surprise, then, that the fastest-growing oil company—or, more properly, “diversified, multi-industry corporation”—is also the most imaginative deployer of capital. The Charter Company, based in Jacksonville, Florida, reported profits last year of $365 million, up 1469 per cent from 1978, and its return on investment of 56.5 per cent was the best in the Fortune 500 list. (By the way, you will find no apologies for profits here. Charter’s is the bubbliest, most joyous annual report of them all, full of smiling and laughing faces that are obviously proud to be rich and eager to get richer.) Charter needed four pages of fine print to list the several dozen products and services it provides, but the ones that got my attention were direct-mail seafood (through a subsidiary called Charter Ocean Products), Alaskan salmon ranching (through a subsidiary called Anadromous, Inc.), and porcelain plates and “medallic art” for collectors, sold by another of its divisions. Charter also owns Ladies Home Journal, Redbook, and Sport magazines, not to mention radio stations in five cities.

Mobil made the most conspicuous contribution to American culture—the manufacture of the cardboard boxes used to package Burger King’s Whoppers. Not to be outdone, Standard Oil of Indiana dominated the market last year in polyester beverage bottles (lightweight throwaways now used by Coke, Pepsi, and all the other big soft-drink companies), with six factories going full tilt in an effort to make the glass soft-drink bottle obsolete. Cities Service and Atlantic Richfield both did a brisk business in trash-can liners, while Tenneco led the world in the manufacture of a specimen of digging equipment called the loader-backhoe. Ashland Oil gets an honorable mention for the wide-ranging exploits of its construction arm, which specializes in highways and parking lots throughout the South, including the Woodall Rodgers Freeway, a giant mess just north of downtown Dallas.

Other companies demonstrated a special proficiency in farming. The leader by far, weighing in with more than 800,000 acres, is Tenneco, which donned bib overalls last year to cultivate pistachio nuts, almonds, dates, raisins, and wine grapes, most of them grown in Southern California. Tenneco also has a chain of retail stores called House of Almonds. Murphy Oil, which is the only major American oil company with headquarters in the backwoods of Arkansas, has 261,000 acres of timber, soybeans, cotton, rice, and wheat. (Judging by its annual report, Murphy hasn’t drilled for oil in Arkansas for years, but it is one of the largest players in the North Sea, Canada, Gabon, and the Gulf of Mexico.) After Murphy comes Getty, with 109,000 acres of almonds, grapes, and citrus fruits in the San Joaquin Valley; Superior Oil, yet another pistachio, almond, citrus, and grape purveyor; and Standard Oil of California, which also farms the San Joaquin Valley.

Sex and the Single Fluid Catalytic Cracking Unit

Fluid catalytic cracking units were very popular last year. It seems that no refinery can do without one. In fact, baffling refinery equipment of all sizes and shapes was being installed along the Texas Gulf Coast as fast as the oil companies could get it built. There were basically two reasons for this. The first is that fewer cars on the road today use leaded gasoline, and so several of the major retail chains stopped selling leaded premium grades of gasoline altogether. Unleaded gasoline requires a more complex refining process, and most of the older plants didn’t have the capacity to produce enough of it. (This was one reason for the long gas lines of last May and June.) The second reason is that low-sulfur oil—so-called sweet crude found in northern Africa and the Middle East—grows more and more scarce as the OPEC countries cut back on their production. That means the oil companies had to settle for crude oil with a high sulfur content, requiring yet more extensive refining to break it down into usable form. The result was a banner year for photographers attracted to shiny silver machinery.

Macho machinery is what separates the real oil companies from the pretenders, and no one has the spirit like Conoco. Its full-page rendering of a new fluid catalytic cracking unit at the Lake Charles refinery fairly glows with white heat, its labyrinth of pipes and towers exposed to the heavens like the innards of a mechanical monster. That photograph is a throwback to the day when all you needed for an annual report were a few good shots of tankers, pumps, wells, derricks, and pipelines spread around a forceful letter written in the stentorian tones of a company that knew what it was doing: we made a big pile of money last year and we’re trying to do it again. In fact, there are still a few of the old warriors left. American Petrofina is a good example. You won’t find any golden sunsets or fancy artwork here. The cover is a fine photograph of a mass polymerization unit at a chemical plant in Calumet City, Illinois, and the rest of the report is devoted to derricks, computers, and refineries. In general these companies make no bones about profits either—Petrofina’s were up 157 per cent—and you will look in vain for any reference to public service, charity, minorities, or appeals to patriotic pride. Marathon (profits up 44 per cent) leads off with three pages of photographs of refinery equipment—including a fluid catalytic cracking unit on the cover—and moves on to offshore platforms, West Texas drilling rigs, the skyline of Garyville, Louisiana (which is much like the skyline of Port Arthur), supertankers, service stations, and laboratories.

Others in the macho photography category include the covers for Standard Oil of Indiana (a drilling crew about to heave a bit into the Overthrust Belt of Utah), Murphy (a massive New Orleans refinery looming in the distance), Crown Central Petroleum (the new Houston refinery bathed in a yellow glow), and Ashland Oil (a liquefaction plant seen from the base of a pile of coal).

Ayatollah Khomeini’s Persian Bazaar

In spite of the fact that 1979 was the year the West lost Iranian oil for good, the oil companies’ circumspect references to “political circumstances’’ in that country would seem to indicate that we all got worried for nothing. Four companies with large Iranian supply contracts breezily dismissed the loss in a few sentences. “Due to the current situation in Iran,’’ reported Texaco stiffly, “discussions with the National Iranian Oil Company have been suspended.” Similar statements emanated from Standard Oil of Indiana, Shell, and Atlantic Richfield.

But three other companies—Exxon, Amerada Hess, and Murphy—deserve a special citation for continuing to haul crude out of the country even while the Shiites were howling through the streets of Tehran. Exxon treats the whole thing as a simple labor problem—“oil-worker strikes” in some of the fields—that had been worked out just fine up until November, when “the Iranian government embargoed all liftings.” Note the lack of reference to the sitting American president’s well-publicized embargo on Iranian oil. The implication is that as long as the Iranians were amenable, Jimmy Carter’s orders didn’t matter, especially since Exxon could just as well have processed that oil through its refineries in Europe, thereby avoiding any ban on “Iranian imports.” Until the liftings were cut off, Amerada was taking 265,000 barrels a day, Exxon 70,000, and Murphy 10,000. How they managed to do this— when other American companies were cut off completely for the entire year—is nowhere revealed.

The Geological Formation Blues

I am speaking, of course, of the Baltimore Canyon, off the shore of New Jersey, which may set records for the expense of its dry holes. Two of the losers, Gulf and Shell, have written it off entirely. Sun hasn’t found anything yet but wants to drill awhile longer. In fact, the only company that seems at all enthusiastic about the place is Texaco, which has struck natural gas in the canyon not once but twice. Tenneco reported the only well to strike oil, but the quantities may not be commercial.

The real action last year was elsewhere in North America, and the sites were familiar: the Gulf of Mexico (still the hottest exploration area), the Beaufort Sea off Alaska, the Williston Basin of North Dakota and Montana, the Overthrust Belt of the Rocky Mountains, and the seemingly bottomless fields of Texas, Oklahoma, and Louisiana. Without being explicit, most of the companies gave the decided impression that they are becoming much less enthusiastic about Third World drilling, with the exception of politically safe areas like the North Sea (every company has a connection there), offshore Malaysia and Indonesia, offshore China, and the tiny country of Oman, perhaps the most staunchly pro-American nation in the Middle East. The exception to the rule was Texaco, which still gets 77 per cent of its oil from the Eastern Hemisphere. Texaco is literally going to the four corners of the earth, having struck oil in the Amazon Basin last year, and plans wildcats in 29 countries this year.

The industry’s top risk-taker, though, was Standard Oil of Indiana, which drilled a remarkable 622 wildcat wells, most of them in the United States. The only two companies able to increase production consistently over the past five years were Superior Oil and Tenneco, both based in Houston. The best luck belonged to Tenneco, which not only had record production last year but actually increased its reserves by 8 per cent through drilling. Other companies also increased their reserves, but usually through acquisitions instead of new discoveries.

Life Is Brief, But Film Is Forever

Unless you are twenty years of age or younger, you may not have seen a film series called American Enterprise. But more than a million people will see it this month, a million more the month after that, and so on into the foreseeable future. That’s because Phillips Petroleum, the producer, has a captive audience. American Enterprise, trumpeting the virtues of laissez-faire economics, has been shown in 62 per cent of all junior high and high schools in the United States, which makes it the most successful “educational” film series ever made. Phillips is so pleased that last year another series, called The Search for Solutions (titles are not one of Phillips’s strong points), was introduced.

Phillips promotes its film ventures in a section of its annual report called “Corporate Citizenship,” a catch phrase used by oil companies to describe any activity that by its nature does not produce a profit. A typical “citizenship” report will include everything from number of speeches given by corporate executives (Phillips officers gave 250 last year) to advertising campaigns to car-pooling schemes to money spent for environmental protection (most of it mandated by the federal government). Phillips is a little old-fashioned in the citizenship department, since the industry custom of producing filmstrips titled How We Search for Oil is giving way to a trend toward High Art.

Exxon, for example, was one of the largest underwriters of the Public Broadcasting System last year. You may have heard of the plan to air all 37 of Shakespeare’s plays over the next six years—even the bad ones like Titus Andronicus. For that you may thank the nation’s largest company. Exxon also sponsors a series called Great Performances, a title that refers not to its 1979 consolidated financial statement but to performers like Joan Sutherland and the New York City Ballet. Exxon’s projects, unlike Phillips’s, fairly reek of the high cultural tone favored by the critics at the New York Times.

The only oil company with equally esoteric tastes is Occidental Petroleum, which maintains a dazzling collection of art through the Armand Hammer Foundation (Hammer is chairman of the board and chief executive officer). Last year the collection traveled to Stockholm and Houston, while an exhibition of the works of Honoré Daumier went on display in Los Angeles and, with considerable fanfare, at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington. Through Occidental’s close ties to the Soviet Union, the company was also able to bring an important collection from Leningrad’s Hermitage Museum to several American cities. But perhaps the most unusual expenditure of all was Occidental’s sponsorship of a French foundation called the International Institute of Human Rights, which held an international peace conference on Campobello Island last year. Campobello Island, off the coast of New Brunswick, was itself donated to the U.S. and Canadian governments by Armand Hammer.

Despite Texaco’s heavy commitment to oil from the Third World, its taste in the arts is confined to the U.S. For the fortieth year Texaco sponsored radio broadcasts (and one television broadcast) of the Metropolitan Opera, and it brought us yet another year of Bob Hope specials. Other dabblers in broadcasting were Gulf (National Geographic specials) and Conoco (a new PBS series featuring social scientist Ben Wattenberg). More traditional were a free-enterprise propaganda campaign, “Teachers in American Enterprise,” introduced into Ohio and Alaska schools by Standard Oil of Ohio, and a Standard Oil of California traveling museum exhibit called “Creativity: The Human Resource.”

The distinction of contributing the most money to the most obscure causes should be shared jointly by Exxon, for making a large grant to something called the University of Delaware Center for the Study of Values, and Getty, whose program for minority education consisted of scholarships at such academic giants as Whittier College, Pepperdine, and the Oklahoma State University department of elementary education. A special plaudit should go to Cities Service Company, whose idea of “corporate citizenship” is contributing $12,120 to candidates for the Canadian parliament and the Louisiana legislature.

Washington Besieged

Eddie Chiles is not the only guy who’s mad. Few oil companies passed up the opportunity to take potshots at the Congress, the president, or—most popular target of all—the Department of Energy. You won’t find anything original in all this, but the usual spiel bears repeating: The nation needs more energy from domestic sources, and we’re the most talented people in the world when it comes to finding and producing it. The trouble is, we can’t drill for oil because all the best places are held by the federal government and barred from exploration because of fuzzy-headed environmentalists. We could mine all the coal the country needs for the next hundred years, but the government insists on prohibitively expensive pollution equipment that no one can afford. The ground is full of uranium, but the nuclear building program has been pushed far behind schedule by irresponsible doomsayers with clout in Washington. Even when we do manage to produce a little oil or natural gas while our hands are tied behind our backs, the government rushes in to levy a tax, control our selling price, and reduce our profit margins to the point where we can’t afford to do much exploration. Now the government says it wants to decontrol oil—so that we can start exploring again—and then it turns around and levies a multibilliondollar “windfall profits” tax on oil at the wellhead. The saddest part is (and here’s the refrain that echoes through all of these reports) it’s the consumer who suffers most of all.

At least 28 of the companies used some version of that diatribe—American Petrofina passed up the opportunity, perhaps because it is run by Belgians, and Atlantic Richfield adopted a stoic attitude, even grudgingly admitting that the windfall profits tax won’t hurt that much—but the ones that seemed angriest were Phillips, Gulf, Standard of California, and Standard of Ohio. Notably tame were the comments of Mobil, which runs its anti-government campaign year-round on the op-ed page of the New York Times and other newspapers.

Odd Man Out

Perhaps the only oil company in America that actually supports the windfall profits tax is Ashland Oil, which spent a good part of last year selling off almost all of its oil and gas wells. The reason is that early in 1979, its officers put pen to paper and discovered that by their reckoning, any increase in the value of crude oil would be offset by taxes, especially the windfall profits tax that they now support. By selling all of their properties in the United States, Canada, and the North Sea, they received payments of more than $1 billion, which they now intend to use to buy companies that have higher rates of return than oil and gas do. This might lead you to believe that Ashland is no longer an oil company—but in fact it still derives 80 per cent of its income from petroleum. How? By using Department of Energy regulations to force other oil companies, including one that is smaller than Ashland, to sell Ashland enough crude to keep its refineries running at full capacity, its pipelines full, and its Save Mart and Superamerica service stations supplied with gasoline. Ashland also buys large volumes from OPEC countries.

The only oil wells Ashland is interested in are so-called stripper wells, those that produce less than ten barrels a day. Because the oil from stripper wells isn’t regulated, it brings up to $30 a barrel in the open market. “As a result of Ashland’s recent reorganization,” writes chairman Orin E. Atkins in his letter to shareholders, “the company is now in the strongest financial and operating condition in its history.” Ashland’s profits were up 24 per cent last year and its return on investment of 54.4 per cent was second only to Charter’s.

Following Ashland’s lead was Clark Oil and Refining, which reported its best performance in history, with profits up 418 per cent. Clark, too, discovered that there is no money to be made in producing energy, and so it sold 100 per cent of its oil and gas properties—most of them in the Gulf of Mexico—in order to “convert underproductive assets to cash for redeployment.” Like Ashland, Clark made a killing on its refining and retailing operations, and it plans to buy “diversified” properties with some of that cash.

Finally, American Petrofina participated in drilling only 39 wildcat wells last year but still had profits up 157 per cent due to the fact that 38 per cent of its oil comes from stripper wells.

Before you start to believe that there is no longer a profit to be made in drilling for oil, consider the case of Gulf, the nation’s fifth-largest oil company, whose profits were up 68 per cent. Gulf was also busy selling off assets last year, but none of them were oil reserves. For a total of $300 million, Gulf unloaded a half-dozen businesses, including an interest in ESAF, a big French oil company (sold to Exxon); an interest in Petronor, a refiner and marketer in Spain; a Montana coal mine; a propane business in the Southeast; and a real estate development in Reston, Virginia. Gulf is negotiating the sale of all its West Coast refining and marketing operations as well. But Gulf was also buying. The company spent $121 million for an unknown oil firm called Amalgamated Bonanza Petroleum, Ltd. All that company had was prime drilling property, most of it in Brazos County in the shadow of Texas A&M.

How Big Fish Get Bigger

There is nothing new about big oil companies devouring little oil companies. The difference last year was that big oil companies were devouring all kinds of companies, and some of them weren’t so little. The year began with Exxon’s announcement that it intended to acquire Reliance Electric Company, a major innovator in electrical motors that ranked in the Fortune 500. After a public outcry, a congressional investigation, and the introduction of a tough new antitrust bill in the Senate, the year ended with Exxon’s doing exactly what it had said it would do. In the meantime, Shell was engineering a less publicized takeover of Belridge Oil Company, which owned huge reserves of heavy oil in Kern County, California. When the deal was finally closed, it was the largest commercial acquisition in history. For $3.6 billion, Shell increased its domestic reserves by 44 per cent.

With so much action at the top, it was easy to overlook the fact that almost every other oil company in America was doing exactly the same thing. Mobil bought a company called General Crude Oil for $792 million. Charter spent $480 million for a bankrupt refinery in the Bahamas, and by year’s end had turned it into one of the oil industry’s best money machines. Standard Oil of Indiana paid $462 million for Cyprus Mines Corporation, an old, established copper-mining company. And when Ashland Oil started selling off its oil wells with such a mad passion, Tenneco and Mesa Petroleum of Amarillo were there to gobble them all up. Tenneco, Charter, and Crown Central Petroleum all bought life insurance companies, while Standard Oil of Ohio snapped up two obscure companies in Denver that together held more than a million acres of oil and gas leases in the Rocky Mountains.

It would be impossible to list all the companies that disappeared last year, but among the notable ones that vanished into the maw of the big oil firms were Rio Alta Mineral, a uranium company bought by Tenneco; Falcon Seaboard (coal) and S.A. Argus Chemicals N.V. of Belgium (polymer additives), both bought by Diamond Shamrock; Reserve Oil and Gas, acquired by Getty; and Carboline Company (industrial coatings), Elk River Resources (coal), and American Electric (fasteners and fluid power equipment), all purchased by Sun.

Memorable Understatements

It is sometimes necessary, in the preparation of an annual report, to use euphemisms. Nowhere in any of these documents will you find the word “money,” for example. You will find “revenues,” “earnings,” “cash flow,” “expenditures,” “funds,” “income,” and “disbursements,” which all amount to the same thing—money—but which somehow sound a little more elevated and dignified than the real item. In much the same way, there are certain delicate subjects that shouldn’t be brought right out into the open air of explicit lexicology. If the sentence is properly handled, the reader will need to review it at least three times to comprehend it. And the rule to remember is that the more important the subject, the briefer the treatment. The five most memorable examples:

Marathon (explaining why drilling has resumed in Egypt): “The operator has gained access to the Bardawil Block in northwestern Sinai which was previously blocked by political circumstances in that area.”

Standard Oil of Ohio (explaining why its retail service stations are being restructured): “The specter of divorcement legislation continues as a threat to efficient gasoline marketing operations.”

Diamond Shamrock (the last paragraph on page 41): “In 1979 the Company was named a defendant . . . in lawsuits alleging liability arising out of the manufacture and sale to the United States Government during the Vietnam conflict of a defoliant often referred to as ‘agent Orange’ . . . The lawsuits . . . allege that personal injuries have resulted from exposure to Agent Orange.”

Conoco (discussing the future of its mining operations): “An accident, which occurred at the Three Mile Island nuclear electric generating facility in March 1979, increased uncertainty of future uranium concentrate demand.”

Occidental (reviewing one of its subsidiaries, Hooker Chemical): “Substantial progress was also made in developing remedial programs for company-owned former chemical waste disposal sites in Niagara Falls, New York.”

The Bottom Line

I once knew a political science professor who spent two hours every morning assiduously going over the fine print in Pravda and Izvestia, an exercise I regarded as futile academic busywork. One day I asked him just what it was the Kremlin had to say that was so damned interesting. “I don’t pay attention to what they say,” he replied. “I’m looking for what they don’t say.”

In much the same way, it is possible to infer a great deal about the psychology of oil from what is never mentioned in annual reports. For example, I think an intellectually sound argument can be made for allowing oil companies to make maximum profits—even 200 to 300 per cent—under the theory that if we really turn the business of finding oil into a gold rush, then not only will we have more of it but we will have more than thirty or so companies looking for it. As the price of energy rose, conservation would take care of itself, and new ventures in the development of synthetics and renewable sources would burgeon all over the map. This is such a simple Adam Smith argument— greed works for us all—that I’m astonished no oil company is willing to make it. Instead, they defend their profits—repeatedly—from the position that they probably shouldn’t be much larger than they are, but just at the moment they aren’t “excessive.” They insist that all they want is a “reasonable return on investment.” And yet their own figures show that they already have a reasonable return, or at least one that is better than that of any other segment of American industry. By any standard—revenues, profits, return on investment—last year was the best the oilmen have ever had.

But since this remarkable year so far hasn’t produced much more energy than we already had, perhaps a gold rush is not exactly what they’re looking for. Historically, all of the great oil companies, from John Rockefeller’s original Standard Oil right down to the heyday of Standard’s most successful spin-off, Exxon, have not cared much for competition in its crasser forms. Competition is chaotic and disorderly. It leads to wild fluctuations in the market, periods of oversupply and depressed prices followed by bankruptcies followed by undersupply and high prices followed by new competitors followed by another cycle of oversupply, and so on and so on. The only way to avoid that mess is to control every cog in the oil supply machine, from the field to the gas pump, but especially the strategic “narrows” of the market—refining—and anything else that could challenge the preeminence of oil.

Could it be that this is the real purpose of the trend toward diversification? Department stores and circuses might attract headlines, but the truly significant acquisitions are other energy companies. It is nowhere explicitly stated, but the message is obvious: when the nation shifts to coal, or synthetics, or solar, or anything, any oil companies that haven’t made the shift are going to be left behind. That’s why more profits aren’t being spent to find oil; instead they are being used as insurance against the future, to acquire companies that hardly make a profit but have reserves in the potentially competitive areas. This doesn’t say much for Big Oil’s optimism—professed optimism, that is— about the future of exploration.

One further impression makes me doubt the sincerity of the oil companies, and that is the very tone they use to express themselves. At first I dismissed this as the kind of mediocre writing that you can more or less expect from executives trained as engineers or geologists or refinery managers. But then I compared it to every other aspect of the report—sophisticated financial analyses, the best graphic design, first-rate professional photography—and I began to wonder. Why do these things have to use a mealy-mouthed, constipated prose style when there are any number of talented wordsmiths for hire? Then I understood: it is precisely the kind of stuff you read in translations of official Soviet documents. Pravda and Izvestia! It is a style that reflects layer after layer after layer of tiny changes, alterations in wording, minuscule adjustments in tone, until every element of vigor and purpose has been excised completely. It is the work of a committee—judging by these reports, a committee of at least a hundred—who are oppressed by the nervous sensation that a word out of place or a phrase turned the wrong way might bring the world tumbling down around them. It is the style of calculated opacity, and of fear. It’s easy to understand what these companies have to protect. The mystery is what they’re so afraid of.

Oil Slicks

You can’t judge a book by its cover, but you can judge a corporation by its annual report.

An annual report is a corporation’s autobiography. And like most self-regarding art forms, it reveals far more than the author intended. Letting the eye wander to the graphics and prose between the facts, figures, charts, and jargon gives a fairly good idea of how companies see themselves and the world around them. The oil companies below, thirty of the biggest in the United States, are listed in order of their sales last year.

1. Exxon (sales $79.1 billion, profits up 55 per cent). Beginning with the Alaskan Arctic twilight on the cover, the report of America’s largest corporation is cast in muted tones, without superlatives, and with a prose style that could have been concocted by a committee of twelve junior-high textbook authors grown tired of life.

2. Mobil (sales $44.7 billion, profits up 78 per cent). The report of the industry’s self-appointed apologist would warm the hearts of the Contemporary Arts Museum’s board of directors, but its meaningless slogans (“Imagining tomorrow is our business”) and heavy-handed symbolism (including a bizarre drawing of a crumpled New York Times going up in flames) make it more entertaining than informative.

3. Texaco (sales $38.4 billion, profits up 106 per cent). A no-nonsense bunch (note the bleak offshore platform on the cover), the directors of the third-largest company are partial to deadening prose and pictures of macho equipment, but their report provides the most extensive survey of all operations around the world and a good summary of the company’s greater-than-usual interest in synthetic fuels and gasohol.

4. Standard Oil of California (sales $29.9 billion, profits up 64 per cent). One of the most thorough, attractive, and readable reports, with a minimum of drivel about the national honor, this one mixes the bad news with the good. For example, if you want to know why Socal’s Ortho lawn products aren’t killing as many of your weeds this year, it’s because the government banned Silvex, a potent herbicide ingredient.

5. Gulf (sales $23.9 billion, profits up 68 per cent). Of the major firms, Gulf is by far the most traditional, sticking to the basics of oil, gas, petrochemicals, and a few other minerals. So its annual report is almost a stereotype of the genre, right down to the cover shot of an oil derrick silhouetted against cloudy evening sky, the obligatory group photo of the company directors on the inside front cover, and a bar graph with the bars in the shape of gasoline pumps.

6. Standard Oil of Indiana (sales $18.6 billion, profits up 40 per cent). A bland, generalized survey of everything from plastic foamboard to exotic minerals all but obscures the fact that this company has the most active exploration program in the nation, with large plays in every major drilling region.

7. Atlantic Richfield (sales $16.2 billion, profits up 45 per cent). One of the few majors devoted equally to renewable energy and the dirtier forms of alternate energy, Atlantic Richfield allots a full page to solar. It is also the softest on government and a tireless promoter of such noble concepts as conservation, facts that qualify Arco as the closest thing to a liberal oil company known to man.

8. Shell (sales $14.4 billion, profits up 38 per cent). President John Bookout is apparently one of the few oil men who can write clean, declarative sentences, so Shell has the most readable report of them all. Its attention to detail provides a clear, coherent overview of all Shell ventures, large and small, including the intriguing news that the company sold the division that makes its most visible consumer product (next to gasoline), the No-Pest Strip.

9. Conoco (sales $12.6 billion, profits up 81 per cent). Conoco takes beautiful pictures of machinery and firmly believes it would have more machinery to take pictures of if the government would get off its back. Its only liabilities in 1979 were a surplus of uranium and seven “fatalities” in its coal mines, minor setbacks in what chairman Ralph Bailey describes as an “extraordinary” year. The company also changed its name from Continental Oil to Conoco, since that’s what everybody calls it anyway.

10. Tenneco (sales $11.2 billion, profits up 26 per cent). Perhaps the most diversified of all the majors, Tenneco leads us on a tour through the worlds of life insurance, shipbuilding, farm equipment, and chemicals—all of which is fascinating compared to its stolid laundry list of drilling tracts and leases, supported by hackneyed pictures of hardware and products spread on tables.

11. Sun (sales $10.7 billion, profits up 69 per cent). For a $10 billion oil company, the nation’s eleventh largest, Sun has put less hard information in its annual report than any other firm; it is filled mostly with smiling faces and paeans to freedom, goodwill, and the American way.

12. Occidental (sales $9.6 billion, profits up 8283 per cent). Occidental had such bad luck in 1978—the shutdown of two European refinery projects, a major coal strike, a major railroad strike—that its profit figures aren’t quite as exorbitant as they look, though the company feels no need to make apologies for them. But for a year that included the Love Canal fiasco (courtesy of its Hooker Chemical subsidiary) and a new cold war atmosphere (hampering Occidental’s extremely close ties with the USSR), the figures aren’t bad.

13. Phillips (sales $9.5 billion, profits up 24 per cent). Very thorough and thoroughly boring, this report contains everything you would ever want to know, and a lot you wouldn’t, about worldwide petroleum geology, cyclic chemicals, and gasoline additives, complete with fuzzy pictures of men at work that are enough to make the eyes glaze over.

14. Standard Oil of Ohio (sales $7.9 billion, profits up 164 per cent). Sohio, king of the Alaskan oil fields, has an eye for graphic design, demonstrated by the first successful picture of a pipeline (descending an Alaskan slope as though it were a ski lift) I have ever seen. By reading the fine print, you can learn that Sohio is now controlled by British Petroleum, which holds 53 per cent of the stock.

15. Union Oil of California (sales $7.6 billion, profits up 31 per cent). Unconventional Union is the world’s largest producer of geothermal energy (in Northern California and the Philippines), the world’s largest producer of rare earth products like europium and yttrium, and the largest real estate developer in Schaumburg, Illinois. One of the directors is Donn Tatum, chairman of the board of Walt Disney Productions.

16. Amerada Hess (sales $6.8 billion, profits up 265 per cent). Filled with warm tones and bright colors and printed on paper as thick as a redwood, Amerada’s annual report mildly castigates Carter for cutting off its bonanza of Iranian oil, launches into a blow-by-blow of drilling tracts around the world, and concludes with a dazzling spread of monster equipment called “Quest for Energy” that rivals National Geographic for technical brilliance.

17. Marathon (sales $6.7 billion, profits up 44 per cent). Thanks to more or less reliable contracts with OPEC countries and a half-interest in the fabulous Yates Field in Pecos County, Marathon was able to keep its customers supplied with 100 per cent of allocations even during the darkest days of the gas lines. The only picture involving identified humans shows the three top executives looking pleased as punch.

18. Ashland (sales $6.5 billion, profits up 115 per cent). Most of these profits came from the sale of oil and gas wells, which didn’t make enough money to suit Ashland. Things that did, richly illustrated in this colorful report, were refineries, aromatic-chemical plants, coal mines, highways (Ashland is building them all over the South), Mario Andretti (sponsored by Valvoline, one of Ashland’s top products), and doughnuts (now sold at Save Mart service stations).

19. Cities Service (sales $6.3 billion, profits up 72 per cent). This is the only company already producing synthetic fuels on a commercial scale (in Alberta), the only company to advertise its political contributions, and the only company affected by a six-week strike at a plastic housewares and trash-bag plant. The entire report is illustrated with watercolors of the type that can be purchased at any Stuckey’s gift shop.

20. Getty (sales $4.8 billion, profits up 83 per cent). In the world of Getty, everything is pictured against a dark, brooding background of blacks and deep blues, including a giant phallic pump nozzle pointed in the general direction of the camera and labeled simply with the word “Marketing.”

21. Charter (sales $4.2 billion, profits up 1469 per cent). This one gets an A for enthusiasm, an A-plus for candor. The picture of a hearty, laughing chairman of the board Raymond Mason is accompanied by a financial analysis making it clear that Charter will invest in anything that makes money, whether it be oil, widgets, or Iranian flags, and sell anything that does not.

22. Kerr-McGee (sales $2.7 billion, profits up 35 per cent). This company works quietly in the production and refining end, with only a few retail outlets, and its report might make fascinating reading for engineers and chemists. One interesting fact: Kerr-McGee’s chemical division is manufacturing an essential ingredient for rocket fuel.

23. Diamond Shamrock (sales $2.4 billion, profits up 28 per cent). A dry, straightforward report; the company’s extensive involvement in complex chemicals makes it tough on the lay reader. Diamond Shamrock nobly avoided any snide references to Cleveland’s ex-mayor Dennis Kucinich, the man partly responsible for its flight to Dallas.

24. Pennzoil (sales $2.1 billion, profits up 86 per cent). Much of its earnings came not from oil but from extensive copper mining in Arizona, part of a diversification strategy that has led Pennzoil into potash, gold, silver, sulfur (it owns the free world’s largest mine, near Culberson), and molybdenum, an element used in steel alloys.

25. American Petrofina (sales $1.6 billion, profits up 157 per cent). With pictures that look as if they were taken with a Polaroid, this report has nothing attractive about it except the bottom line, most of which was derived from record sales of gasoline.

26. Murphy (sales $1.6 billion, profits up 122 per cent). Involved primarily in production and refining, Murphy has managed to stay ahead by diversifying into timber, wildcatting very selectively in exotic locales, arranging supply contracts with OPEC, and keeping its refineries (the real vortex of profits) running full steam.

27. Commonwealth Oil Refining (sales $1.2 billion, profits up $135 million). Record earnings don’t mean much for a company that’s been in bankruptcy for two years and continued to lose money in 1978. Corco opted for the cheapest paper, two small black and white pictures, and a long and complex account of just how it got into this fix and how it intends to get out. Despite all the bad news, it was still one of the nation’s largest oil companies.

28. Clark Oil and Refining (sales $1.2 billion, profits up 418 per cent). A refiner and marketer making a fortune by processing imported crude and piping it to jobbers and 1300 service stations that are rapidly being converted into “grocerettes.” Obviously from a no-frills company, the annual report was printed entirely in black and white.

29. Superior (sales $1.1 billion, profits up 106 per cent). The gloomy photography—gray skies brooding over the bleakest of oil-field landscapes, like sets from Waiting for Godot— belies the fact that Superior is one of the few companies able to increase their oil and gas reserves over the past four years.

30. Crown Central (sales $1.1 billion, profits up 285 per cent). One of several companies getting rich through the use of imported oil, Crown is primarily a refiner and marketer. Its slim report is long on wholesome platitudes about “courteous service” and “financial foresight” but short on any real analysis of the energy market.

- More About:

- Energy

- Business

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston