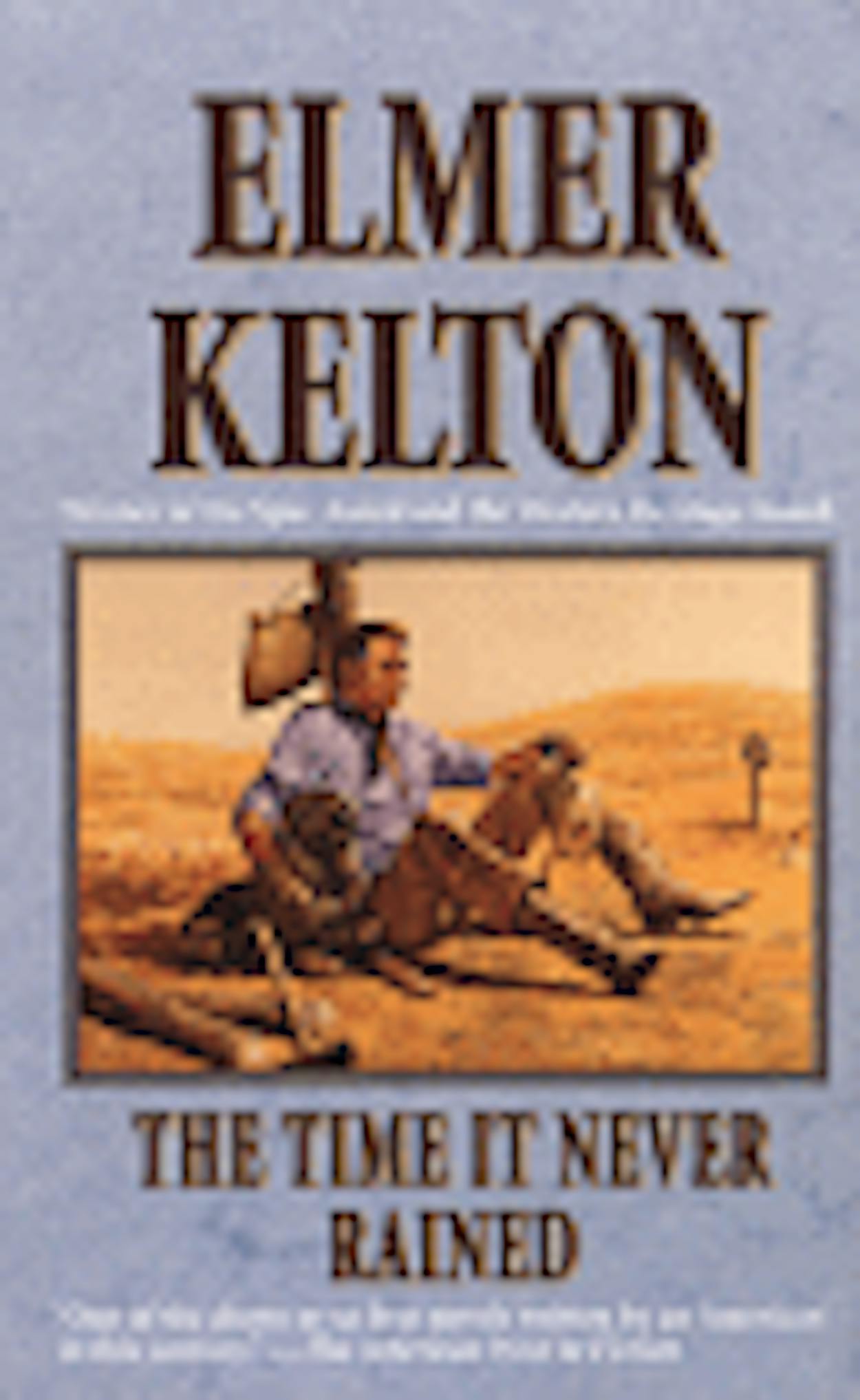

When I was in San Angelo earlier this year, the only thing people wanted to talk about was the prospect for rain. There was none, though heat lightning in the evenings buoyed hopes nonetheless. Hard-pressed ranchers were already taking drastic measures, burning prickly pear to supplement feed for their cattle. All of this should sound familiar to fans of Elmer Kelton, San Angelo’s favorite writer and the author of a book with one of the all-time great Texas titles, The Time It Never Rained. Asked today if that title still applies, 27 years after its publication, Kelton says, “Look out the window.”

The novel traces the actions of a proud and contrary Texas rancher named Charlie Flagg, who struggles to endure the biblical-style drought that devastated Texas agriculture in the fifties. Kelton, for many years a writer for such publications as Sheep and Goat Raiser Magazine and Livestock Weekly, possesses an expert’s knowledge of animal husbandry—for example, screwworms, their cause and cure—and he manages to fit into the narrative all of the workaday drudgery of running a ranch in hard country. About every hundred pages the reader feels like having a glass of iced tea (the drink of choice in West Texas) and wiping his brow from following the daily rounds of real cowboy work.

The Time It Never Rained is chock-full of sagebrush and sage-isms. Part of being a crank is having a lot of opinions, and Charlie’s expressions often sound as if they should appear on a bumper sticker on a Ford pickup: “Treat the land right and it’ll take care of you”; “A boy don’t get to be a man with clean britches on.” Unlike contemporary West Texas novelist Larry McMurtry, Kelton rarely transgresses any regional codes. He housebreaks even the most famous of sayings, writing “He couldn’t pour water out of a boot if the instructions were printed on the heel.” The way I always heard it, it was a four-letter word that somebody was too dumb to pour out of a boot.

Charlie’s stubborn tenacity and gritty integrity are what make him, finally, a convincing and memorable character. He loses a son to the glitz of the rodeo, a loyal Mexican American family to better prospects in town, and all of his heifers and bulls. It’s just one damned thing after another, until finally he is left with nothing but a bunch of goats to raise. Then, all of a sudden, a hard rain breaks the drought, but it causes the newly sheared goats to die from exposure. In the end Charlie, his wife, and two young hands are in the pastures trying to shelter their flock. His pride lies in never having taken a dime from a federal hand-out program, and his rock-ribbed self-reliance taps into one of West Texas’ most deeply cherished beliefs about itself.