In early 1994 Laura Bush wasn’t crazy about the idea of her husband running for governor of Texas. When he decided to run anyway, she made it clear that she wasn’t going to be one of those wives who are always by their husbands’ side. She liked being at home, reading books and taking care of their twin daughters.

It wasn’t that the former elementary school teacher and librarian was painfully shy; she just wasn’t all that interested in living a public life, nor was she used to one. Her husband, George W. Bush, had run for office only once before—he’d sought a congressional seat in West Texas in 1978—and he had lost. One day during that campaign, he had to miss a rally in the town of Levelland and begged Laura to go in his place. She reluctantly agreed. When she got there, she rose and repeated a line she had memorized earlier that day. “My husband told me I’d never have to make a political speech,” she said. “So much for political promises.” Then, forgetting the rest of her speech, she nervously mumbled a few words about George’s good qualities and sat down after only a minute and a half.

Fast-forward eighteen years to the Republican National Convention in San Diego. On August 12, 1996, Laura Bush strides to the podium to give a brief prime-time speech on the importance of literacy. “Reading is to the mind what food is to the body,” she says in calm, measured tones. “And in Texas, nothing will take higher priority.” Her husband, sitting onstage as a co-chairman of the convention, stares at her with what one of his aides will later describe as “a face filled with awe.”

Until Texas gubernatorial terms changed from two years to four years in the mid-seventies, most first ladies had little time or inclination to make names for themselves (Nellie Connally excepted). In the four-year era, however, they have become much more visible: Linda Gale White, the wife of Mark White, gained notice for promoting a program to keep kids in school, and Rita Clements, the wife of Bill Clements, made news by raising more than $2 million to renovate the Governor’s Mansion. Yet no first lady has received anything like the attention that Laura Bush has. “For as long as I’ve known her, this is someone who has steadfastly refused to pursue the limelight,” insists Regan Gammon, her best friend since the third grade. But there’s no denying Laura’s high profile. Just as some people are curious to see if George will become as prominent as his father, others wonder if she will turn out to be as popular as her mother-in-law, Barbara Bush, one of this century’s best-loved political wives.

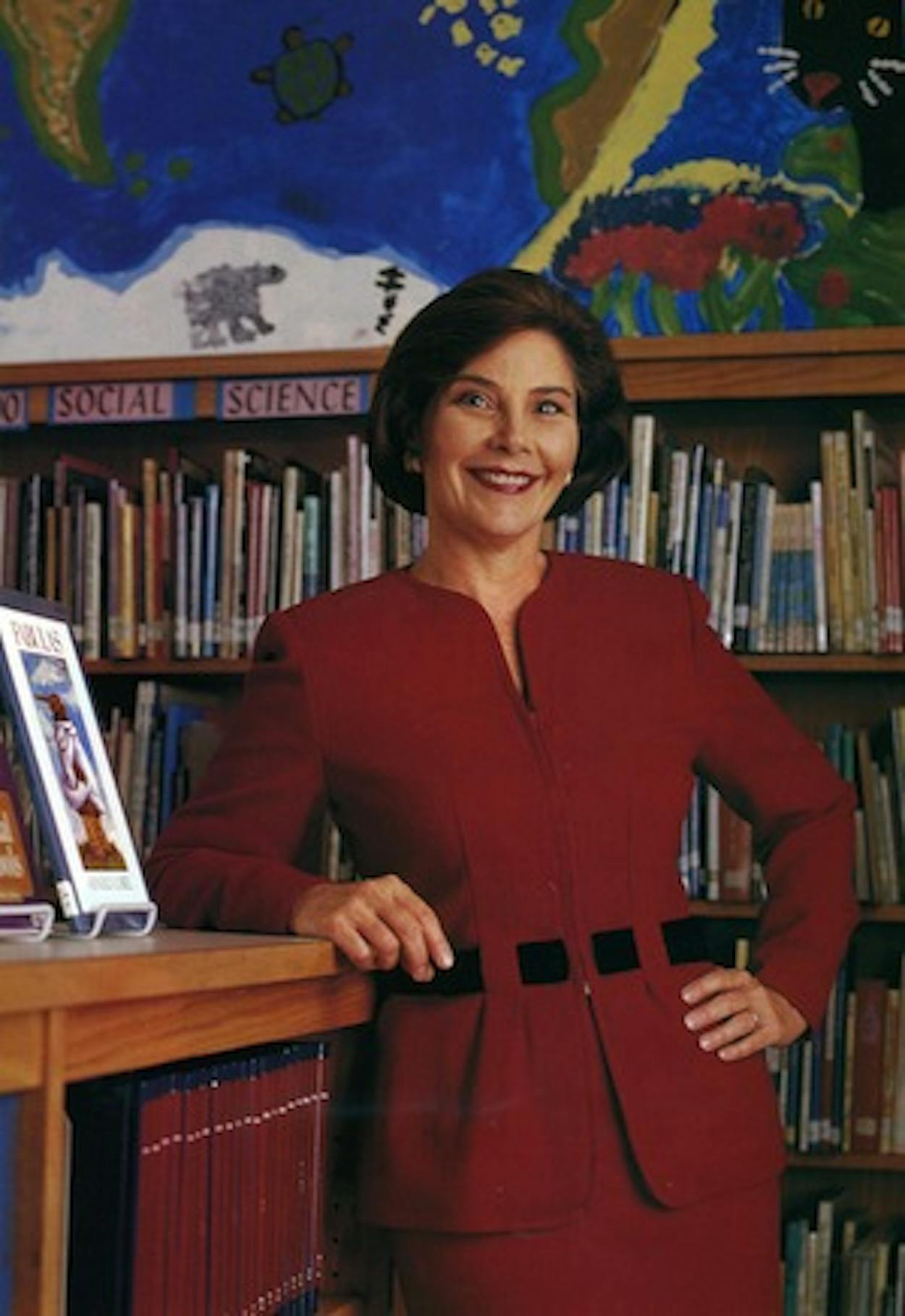

“Oh, please, Bar is very funny, very acerbic, very entertaining to listen to,” Laura recently told me as she sat with one leg folded underneath her in her small windowless office in the basement of the Capitol. “I’m, well, none of those things.” At fifty, she is a pretty woman with startling blue eyes who wears tailored suits that she buys at chic Dallas boutiques. But compared to her famously ebullient husband—when I walked into his office to interview him for this story, the fifty-year-old governor stood up behind his desk, pumped his fist in the air, and shouted, “Dude!”—Laura is unassuming enough that she is often overlooked in public. Watching her at a party at the Governor’s Mansion after the Notre Dame—University of Texas football game in September, I noticed that she preferred standing at the edge of the crowd, chatting quietly with friends. A few days earlier, at a large society gala at Dallas—Fort Worth International Airport, I watched her slip in so unobtrusively that people at the tables next to hers gasped in surprise when she was introduced and asked to stand.

Yet despite her innate reserve, Laura Bush has begun to transform herself into one of the most effective first ladies in Texas history. She is leading a statewide campaign to raise money to improve community literacy programs. She has become a vocal promoter of literary Texas, creating the first-ever Texas Book Festival (to be held this month in Austin) and personally soliciting the participation of more than one hundred Texas authors, including Larry L. King and Larry McMurtry. And she has forged an alliance with Jan Bullock, the wife of Democratic lieutenant governor Bob Bullock, and Nelda Laney, the wife of Democratic House Speaker Pete Laney, to persuade collectors of nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century Texas art to donate all or part of their holdings, which would be exhibited in the restored Capitol.

“You have to remember that this was a woman who used to think a good speech was putting her finger to her mouth in a school library and telling her students, ‘Shhhh,’” jokes George W. Bush. “To me, it has been remarkable—and I emphasize the word ‘remarkable’—to watch what has happened to her.”

So far, the only controversy surrounding Laura Bush is whether she and the governor knew each other when they were attending the same junior high school in Midland. Laura says she thinks George knew who she was. George insists that he knew who she was. But Laura’s mother, Jenna Welch, who lives in Midland, told me the governor “is just being diplomatic—I know he doesn’t remember her.”

When they were growing up in the early fifties, Laura’s father (who died in April 1995) was a credit officer and then a homebuilder. George’s father was an Ivy Leaguer who had come to Midland to make his fortune in oil. Although their homes were in adjoining neighborhoods, the two families didn’t cross paths. The Bushes went to a Presbyterian church, the Welches to a Methodist church. Nor did it seem that George and Laura had anything in common. According to his own mother, George was “incorrigible” and relentlessly sarcastic; Laura was a conscientious student who wore glasses.

Laura stayed in Midland through high school, then attended Southern Methodist University, where she majored in education. George was sent to the exclusive Phillips Andover Academy in Massachusetts and then to Yale University in Connecticut, where he majored in history. Although Laura and George both ended up in Houston in the early seventies at the Chateau Dijon apartment complex, they never ran across each other. Laura, who was teaching elementary school, lived in what she called the “sedate” side of the apartment complex. George, who was driving a snazzy Triumph sports car and flying jets for the Texas Air National Guard, lived in the “wild” side.

In June 1977 they finally met at a dinner thrown by mutual friends in Midland, where Bush, then 31, had moved to start his own oil business. Laura, then 30, was a librarian and teacher in Austin, having graduated four years earlier with a master’s degree in library science from UT—Austin. Why would anyone fix up two people who were so different? “Well,” Laura says with a smile and a shrug, “I guess it was because we were the only two people from that era in Midland who were still single.”

But not for long. Three months after that dinner, George and Laura stunned many of their friends by getting married. “I think it was a whirlwind romance because we were in our early thirties,” Laura admits. “I’m sure both of us thought, ‘Gosh, we may never get married.’ And we both really wanted children. Plus, I lived in Austin and he lived in Midland; so if we were going to see each other all the time, we needed to marry.” Regan Gammon thinks there was less of a practical motive at work: “We quickly realized that they were perfect complements to one another. Laura loved George’s energy, and George loved the way she was so calm.”

For the first fifteen or so years of their marriage, Laura continued to live a quiet life as Bush built his oil business in Midland, moved his family to Washington to work on his father’s presidential campaign in 1987, then to Dallas, where he became the managing general partner of the Texas Rangers. Except for a stint on the boards of several charity groups, she was little known in Dallas. George recalls that when he first brought up the idea of running for governor, she was “the very last one willing to get on that train.” She didn’t want politics disrupting the lives of their daughters, Barbara and Jenna, who were reaching their teenage years, and she wondered if her husband was only running to fulfill his family legacy. When George finally convinced Laura that he truly wanted to lead the state, she agreed to do some limited campaigning, which consisted of giving speeches to GOP women’s groups. Reading carefully from a prepared text—“The idea of ad-libbing scared me to death,” she says—she’d begin with that same old line about her husband promising that she would not have to give speeches. She always spoke briefly and not particularly demonstratively.

Even after George won, many of Laura’s friends expected her to maintain a low profile as first lady. “I knew she was uncertain about moving to Austin,” George says. “She was a little fearful, maybe, about whether any of this life would be to her liking. So my attitude was, ‘Laura, if you want to sit in the Governor’s Mansion during my term in office, that’s fine with me. You and the girls didn’t ask to be put in this position, and I promise I’m not going to make any of you do anything.’” Indeed, Laura has been committed to protecting the privacy of the twins (who turn fifteen this month). To this day, she refuses to allow reporters to interview them, and photographers are asked not to take their pictures. “The girls would be totally humiliated having to do a photo,” Laura says. “And I know this sounds strange, but I’m just not ready to have everyone know what they look like.”

Although it was one thing to maintain the privacy of her daughters, it was quite another for Laura to keep herself out of the spotlight. “I finally said, ‘Well, if I’m going to be a public figure, I might as well do what I’ve always liked doing,” she recalls, “which meant acting like a librarian and getting people interested in reading.” So in her first act as first lady, she invited a group of Texas authors—among them, self-described “flaming liberals”—to read at an inaugural week event. Then she began traveling the state to focus attention on literacy and encourage better reading programs for children. Of course, much was made of the fact that Laura was following in the footsteps of Barbara Bush, who had made literacy her cause when she was first lady of the United States. “I didn’t want to step on Bar’s issue,” she says, “but it had also been my issue long before I became a Bush. And I think Bar loved what I was doing.” In fact, the Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy has donated $150,000 to her literacy program, the First Lady’s Family Literacy Initiative for Texas, which awards grants to deserving nonprofit groups.

Laura says Barbara gave her only one piece of advice about being a politician’s wife: never criticize your husband’s speeches. “She said it would prevent a lot of marital fights,” Laura notes, “and she was right.” Even though she continued to use her George-promised-me-I’d-never-have-to-give-a-speech line, Laura’s own speeches got noticeably better, and she began to learn about the power of her last name. Whenever she showed up in cities or towns, it was front-page news. After meeting the first lady, a wealthy El Paso man named his racehorse Sweet Laura Bush. A businessman emblazoned her name on the gas tank of his Harley-Davidson. And when Laura asked Jan Bullock and Nelda Laney to join her in her project to acquire art for the Capitol, they readily agreed, creating a kind of bipartisan political wives’ club. One morning this summer, I watched them and a few other women visit the home of Dallas collector Claude Albritton, who owns several nineteenth-century bluebonnet paintings by Texan Julian Onderdonk. It was hard to miss Bullock, a striking, outgoing blonde, or Laney, who is charming in a flirtatious small-town way. But where was Laura? She had drifted to the back of the group, letting others take charge. “I think what people see in her is her ability to be just incredibly pleasant,” says Bullock. “In her nice, soft way, she says a few words, and people realize there is nothing phony about her.”

She doesn’t seem overly ambitious either. Laura has no political advisers; her entire staff at the first lady’s office consists of one person, Andi Ball, who does everything from answer the phone to travel with her around the state. Laura insists that unlike, say, Hillary Rodham Clinton, she has no interest in making policy decisions. When I asked her if she would ever lobby legislators to vote for a certain bill, she appeared startled. “Well, no,” she said, “the idea hasn’t occurred to me.” Although she believes teachers should be paid more and that more money should be spent on reading programs, she does not try to persuade her husband to increase state education aid. “She knows that the literacy problem is not so much about spending more money as it is focusing on how the money that we have is being spent,” George says. “Look, Laura and I read the paper together every morning, and we discuss different issues. She’s always asking what I’m going to be doing about this or that. But I think she trusts me to make the right decisions.”

Smart, genuine, independent without being inflammatory, a loving mother and supportive wife: Not surprisingly, Republican leaders see Laura Bush as precisely the kind of political spouse who can appeal to middle-of-the-road voters. And considering that George is already on several short lists as a Republican nominee for president or vice president four or eight years from now, it doesn’t hurt that she’s starting to get good ink. These days a potential first lady of the United States is often scrutinized as closely as her husband. In fact, all the press talked about during the month of August, it seemed, was Elizabeth Dole’s Oprah-style walk-and-talk in San Diego and Hillary Clinton’s defense of her it-takes-a-village message in Chicago.

George maintains that he had nothing to do with Laura’s speaking at the GOP convention—that it was party chairman Haley Barbour who made the decision after he heard her talk about literacy earlier in the year. But the afternoon before Laura gave her San Diego speech, George noticed a gaggle of reporters, cameras, and boom microphones enveloping her on the convention floor. The reporters were asking about her husband’s presidential prospects. She replied that all the attention was flattering, but if a decision were to be made about a White House run, it would not happen for a long time. She smiled sincerely, and the reporters smiled back.

“Right then I realized that the same thing was happening to me that had happened to my old man,” George later said. “I was already becoming less popular than my own wife.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Laura Bush