This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It was one of those hellish August nights when Priscilla Davis and her lover, Stan Farr, had their last drink and drove back to the Davis place. The Mansion it had come to be called, though mansion didn’t do justice to the eye-popping $6 million sprawl of trapezoids and parallelograms and oddly sloping white walls that multimillionaire Cullen Davis had built to immortalize his marriage to Priscilla eight years ago. It was more on the order of a museum, something cool and impersonal and unassimilable, yet awkwardly apparent to the heavy flow of traffic along Hulen Street. Arranged as it was on the knob of a windy hill adjacent to the Colonial Country Club golf course in the heart of Fort Worth, the silhouette protruded from the landscape like an ocean liner.

It was shortly after midnight when Stan Farr opened the heavy iron gates and they started up the hill to the garage. Five mongrel dogs tumbled at Priscilla’s feet as she looked for the key, then she noticed something wrong. Through the glass she could see the lights on the security panel, indicating that someone had opened the door during the three and a half hours they had been gone. Maybe it was Andrea, Priscilla’s twelve-year-old, or maybe Dee, her eighteen-year-old, had come home early. Anyway, the door that opened onto the breakfast room was unlocked.

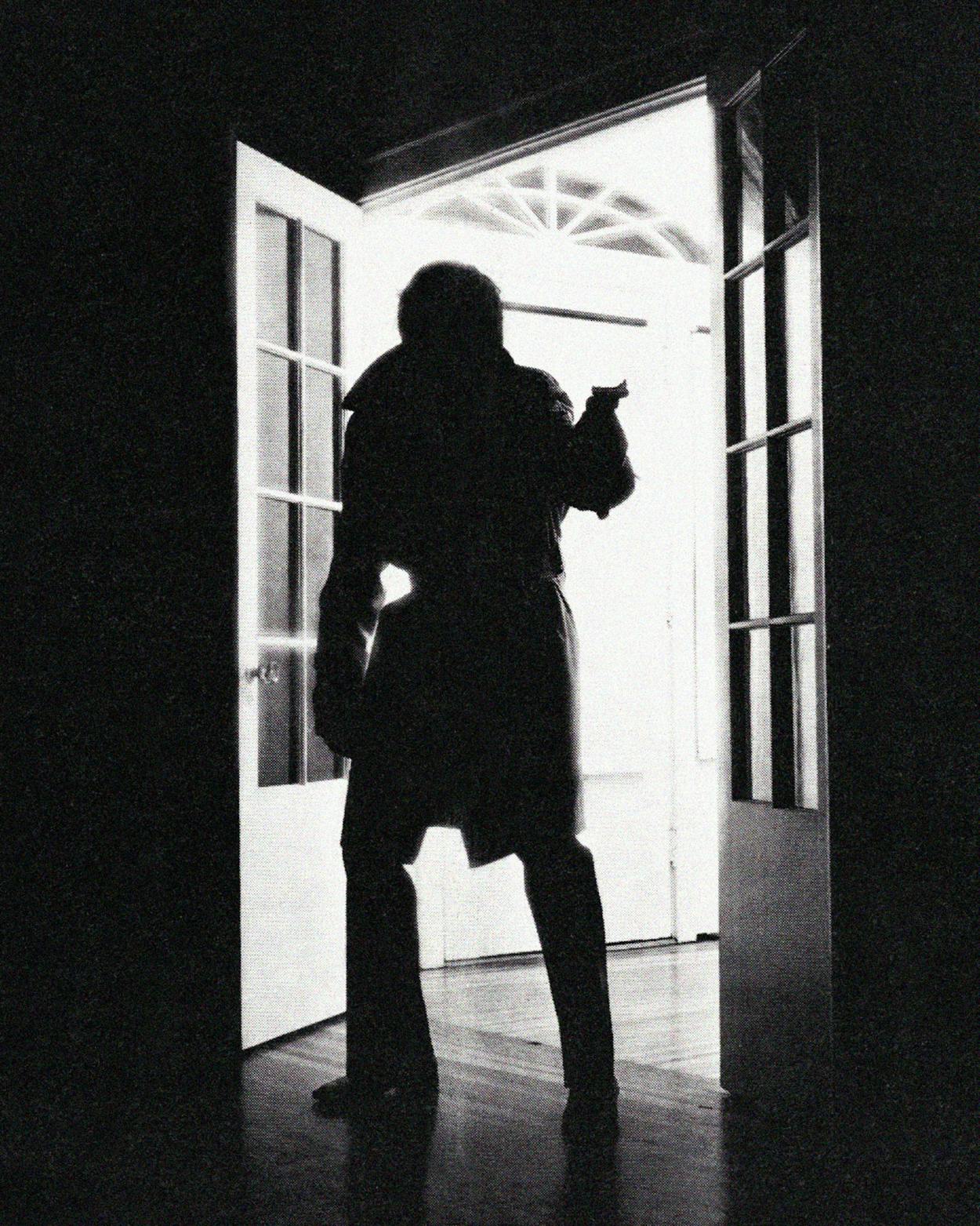

Stan Farr, the onetime TCU basketball player who had taken up residence at the mansion earlier in the summer, headed upstairs to the master bedroom and Priscilla went to turn off the kitchen lights. That’s when she noticed the lights shining unexpectedly in the basement and a bloody handprint on the basement door—Priscilla had no way of knowing that Andrea’s body had already been stashed down there. She took a tentative step toward the basement, then changed her mind and called out to Stan. He probably didn’t hear. As she started for the stairway leading to the master bedroom, a man emerged from the laundry room to her right. He was dressed in all black, wore a woman’s black wig, and kept both hands inside a black plastic bag. He said “Hi,” then shot Priscilla through the chest. At the sound of the shot and the scream, Stan Farr ran downstairs. The man in black shot Farr four times, then dragged him by the ankles to the kitchen. Priscilla staggered to her feet and shouldered open the sliding glass door leading to the courtyard. She held her long denim skirt as she ran, and told herself not to panic. She could feel the blood and the bullet hole through her pink halter top.

Later, she would remember hiding in some shrubs and hearing voices from the driveway. At first she thought it might be Dee coming home, and she thought Oh dear God, no not that!, then she was running down the grassy slope of the 181-acre estate, toward the homes of neighbors she never knew. She heard a scream and more gun shots, but she kept running. She banged on a door, screaming, “My name is Priscilla Davis. I live in the big house in the middle of the field off Hulen. I am very wounded. Cullen is up there killing my children. He is killing everyone. . . .”

Rattling around in her $6 million mansion, Priscilla thanked God Thanksgiving had passed and prayed now to get through Christmas. Sometimes as she fondled Stan Farr’s SAE ring, which fit her finger like a golden doughnut, she heard her own voice asking What could I have done? Sleep came hard and never lasted long. Though the mansion sprawled over more than 10,000 square feet, Priscilla had effectively reduced her living quarters to the master bedroom, the adjacent sitting room with the six-foot TV screen, and the enormous pink bathroom lined on three sides by twenty-foot floor-to-ceiling mirrors. The pink bath was her room, the only one in the mansion Cullen had not personally supervised; with its giant mirrors, sunken marble tub, crystal chandelier, and the catbox next to the bidet, it was the one place that reflected her personality. She loved to sit yoga fashion in front of the mirror, doing her eyebrows.

Mostly she sat on the double queen-sized bed with the silver fox spread and the stuffed animals and yellow-haired rag doll with the pink dress, using the bank of telephone lines to talk to her friends Judy or Lynda, or playing Scrabble or backgammon with Rich Sauer, Stan Farr’s old basketball buddy from his TCU days. There was always an armed guard downstairs, and the panel of lights on the bedroom wall told her that all locks were secure. Without moving from the bed she could adjust the three TV screens or talk to the security men or close the magnificent drapes to blot out the view of the downtown skyline. There was a carton of Eves on the nightstand, laminated photographs of Stan and her children, and dainty little signs, such as the one that said: “Love is being able to let go.”

Life had been reduced to a single ritual: every evening as the sun was going down, Priscilla walked through the mansion closing all the machine-operated drapes. She hardly set foot outside. Friends marveled at her tenacity; how could she stay there in that museumlike chill surrounded by art treasures and pursued by the ghosts of that incredible night in August? Maybe they didn’t understand; she had no choice. It was like a fairytale, only in reverse. Rich little poor girl, a prisoner in her own castle. After all that had happened, the price she had paid, Priscilla was not about to walk away now.

Her oldest daughter, Dee Davis, born eighteen years ago when Priscilla herself was just a teenager, had come home from her freshman year at Texas Tech and personally supervised Thanksgiving dinner. Priscilla was thankful that Dee was alive: the feeling persisted that a mere slip of fate spared Dee that nightmare in August. Priscilla’s son from her second marriage, Jackie Wilborn, had come to the mansion for the holidays. In some ways, Jackie had taken it harder than Dee. Jackie was only fifteen and had never lived under Cullen Davis’ roof; it was difficult for him to understand why a woman like Priscilla, with her natural flash, zest, and taste for the exotic, had not stayed with his father Jack, a man old enough to be her own father. Pricilla’s 71-year-old mother had come over for Thanksgiving and so had a niece and other relatives. What was there to talk about? With the help of a half-dozen TV sets and a blitzkrieg of football, Priscilla had survived the gathering. Her mother was already talking about Christmas, for God sakes. Priscilla wanted to ask her: what makes you think there is even going to be a tomorrow?

The pink heart with the words ANDREA’S ROOM was still on the door. In many ways Andrea had been a woman at twelve. She was five-seven and fully developed, a budding though larger replica of her mother. When Andrea was younger, Cullen called them “my big white pig” and “my little white pig.” But this was the room of a little girl, pink and soft and cuddly, and that’s the way Priscilla insisted on remembering Andrea. “She was so gentle, so quiet,” Priscilla said. “She was just like me—she loved to take in stray animals. She was the kind who could keep a cat and a canary in the same room.” Andrea loved to cook, too. For weeks after the funeral Priscilla would open the hotel-size refrigerator and discover small concoctions that Andrea had stored. Why! Of all the enigmas and impassioned kinks and whims and inexplicable crossings, why Andrea? Stan was in his grave: Stan Farr, “the Bear,” the gentle giant, the former TCU basketball player and lovable hardlucker. That part had to be accepted. Bubba Gavrel, a 21-year-old boyfriend of Dee’s friend Bev Bass, was still partially paralyzed from his gunshot wound. Bubba had had the misfortune to stumble into the night’s carnage. Priscilla suffered from a staph infection and other complications from her own wound, and the ulcer that she had developed from the 27 months of bitter and still unresolved divorce proceedings was getting worse. There were lawsuits and countersuits, lawyers by the package, private investigators trailing private investigators, the press, the gossip about her sex life, and of course the impending murder trial and all that it portended. Millions of dollars were at stake, and so was Cullen Davis’ life: the district attorney was seeking the death penalty. Priscilla had not the slightest doubt Cullen’s attorneys intended to drag her through the mud. They would call her a money-grabbing slut and worse. By innuendo, they would paint her as a Dragon Lady, corrupting youth and even trafficking in drugs. There was even the thought that she might not live to testify. According to her own investigators, a contract had been put on her life. She had been advised to “stay off the street,” and when she did go out, usually late at night and always with close friends, Priscilla wore a silver-plated .32 strapped to a custom-made holster on her right boot.

Priscilla had never been the darling of high society in Fort Worth, not that she gave a damn, but they hadn’t exactly stoned her, either. Now she felt the black crones circling. A group of “prominent citizens,” including Amon Carter, Jr., and power broker Babe Fuqua, were using their weight to have Cullen released on bond. This was no act of charity or friendship but simply good business: every major bank in Fort Worth had a sizable stake in Cullen Davis’ welfare. Cullen owed them $6 million, and he wasn’t much use to them in jail. For the first time in memory the subject of civil rights had a majority of the advocates at the Petroleum Club. The wife of a very rich, very prominent industrialist had telephoned Pricilla and asked her to “let Cullen off the hook.”

“At first I assumed she was talking about the divorce settlement,” Priscilla said. “She pointed out that I had gotten a lot of nice things I never had before. She said how everyone knew Cullen was a weak person, but he wasn’t the only person in the world with money. By now I’m catching on what she’s talking about. She said: ‘Priscilla, I think the best thing for you would be to move out of town and change your name.’ I was dumbstruck! All I could think to say was: ‘We all have to answer to God.’ ”

There were those among Fort Worth’s rich and prominent who expressed sympathy and seemed to understand the full meaning of the tragedy. June Jenkins, wife of author Dan, had written a warm note from their summer house on the island of Kauai. Phyllis Rowan had mentioned something about “getting in touch with Truman [Capote],” who would presumably be interested in writing Priscilla’s life story as a sequel to Answered Prayers. But when the hard core of high society talked about Priscilla Davis, as they did almost every day, they spoke of that platinum hussy with the silicone implants who wore a diamond necklace that spelled out RICH BITCH and took pleasure in dragging her mink across the carpet at Shady Oaks Country Club. Middle society recalled her as that knockout blonde with the enormous breasts and hip-hugger jeans and Indian jewelry who was always getting her picture taken at the Colonial gold tournament—in the words of one advertising executive, “a lady who looked like she had spent too much time in bowling alleys.”

A Fort Worth attorney who had known Cullen since childhood told me: “She’s trash, plain trash.” The attorney looked at his wife for confirmation, then added: “They’re both trash, Priscilla and Cullen, both.” By far the worst gossips, though, were those who knew only what they read, those whom the country club set referred to as “the great unwashed.” My own mother, for example, had heard from a friend whose daughter was a friend of the late Andrea Wilborn that the Davises maintained a private washer and dryer for their dogs. (It was true that the dogs sometimes slept in the mansion laundry room.) Others talked of orgies and two-way mirrors and movie cameras hidden in the ceiling above the master bedroom’s double queen-size bed. There were incredible stories of how old man Davis, founder of the family fortune, “kept her” in Houston before young Cullen moved in (though Priscilla never laid eyes on the old man until his funeral), and a private detective told me that the mansion basement, the place where Andrea’s body was discovered, “was full of whips and leather,” when in fact it was used as a storeroom for spare mattresses and lawn furniture.

For whatever reason, because she had a sense of humor or maybe because the mystique was a handy bridge from where she had come from to where she was going, Priscilla didn’t exactly labor to correct all these impressions. When she granted two Associated Press reporters an exclusive midnight interview in her bedroom, the subject of the ceiling camera naturally came up.

The AP men wrote:

“A woman of some mystery, a target of high and low rumor, Priscilla swept away all pretenses, smiling wryly as she acknowledged talk about a movie camera focused from the ceiling on her bed below.

“ ‘It doesn’t even work,’ she said.

“And filmed lovemaking?

“Again the smile: ‘I know what I’m doing. I don’t need an instant replay . . .’ ”

Priscilla didn’t exactly lie to the AP, but she allowed it to lie in her name. That’s not a movie camera that the boys saw tilting from the ceiling, it’s a fancy light fixture. It’s true that the three-in-one TV console on the shelf across from the bed plays its silent trilogy so long as there are three stations on the air, and it’s also true there is a broken, inexpensive portable videotape camera in what used to be Cullen’s dressing room, and what’s more, Priscilla does entertain guests while seated yoga fashion sipping wine and smoking Eves on the silver fox bedspread—but the connection is in the eyes of the beholder. It is part of Priscilla’s mystique to be both more and less than she appears. In a flat-headed, semi-tough town like Fort Worth, exotic is frequently confused with erotic.

“She didn’t wish for her legal husband to sit in the electric chair, though she didn’t think it would come to that. But when she thought about Cullen on his cot in prison, she then thought of Stan and Andrea.”

What annoyed Priscilla was not the accusations but the omissions. No one, for example, had mentioned her Brownie Troop. Or the fact that she was roommother chairman. Or that she served three days a week with the Red Cross at Harris Hospital. Or that she took ballet at TCU or had logged 23 hours in flying lessons until she broke her ankle skiing. Folks clapped their hands and slapped their knees when they read that all Priscilla wanted from life was “a husband, babies, and a vine-covered cottage.” One thing was sure: she didn’t want what she had, which was both a lot more and a lot less than she had bargained for. Nor did she wish for her legal husband to sit in the electric chair. She knew it wouldn’t come to that, but when she thought about Cullen hangdog on his cot in prison denims with not a corporate telephone or even a radio in sight, she then thought of Stan and Andrea.

“I guess we both did some things to each other,” she said one night as we stood on the mansion’s main balcony, looking over the 181-acre estate. “But this . . . this is what we call no-takesy-backsey.”

Something else bothered her, she told me. People thought of her as a little girl from the sticks who had hit it big. “That’s just not true,” she told me, and the way she said it, you absolutely had to believe her. “My mother always had a good job. She majored in English at USC when we were living in L.A. after my father . . . sort of wandered off. There were always books around. I took piano lessons for four years. I was a good student. I was a member of the student council. Whatever the in thing was, that’s what I was. If I wanted to be a cheerleader, I knew I could get the votes. I had a super childhood. My mother always took the time to see that we were entertained. We had the only swing set and sandpile in our neighborhood when we lived in Galena Park.” Priscilla didn’t remember her father, but she knew he was a rodeo rider and spare-time geologist. In light of this, she found it “ironic that I would turn out to marry an oilman.” She had given some thought to putting a tracer on her father. All she knew about him was what her mother told her: “If you ever met him, you’d like him.” After her father split, it was her mother’s brother, Uncle Guy, who took responsibility for the family, which also included Priscilla’s two brothers, grandfather, and grandmother. Uncle Guy was a blue-collar worker for Brown & Root, and Priscilla used to tell classmates that Uncle Guy built the Gulf Freeway. After she married Cullen Davis, Priscilla moved her mother and Uncle Guy to Fort Worth. She was proud of them. Maybe that wasn’t a lot to hang onto, but there were many prominent people in Fort Worth who hadn’t seen some things she had seen. “People in Fort Worth,” she told me, “enjoy being the big fish in a little pond.”

Moving as she had from one husband to the next, Priscilla never really had time to experience herself. When a friend was down with the flu, Priscilla was the first one there with the hot soup. “Good old practical mother Davis,” she sometimes called herself. She was barely sixteen when she married Dee’s father, Jasper Baker, a 21-year-old ex-Marine. The marriage lasted about a year. Then she met a 40-year-old used-car salesman named Jack Wilborn. “I wanted a home for Dee,” she said. “Jack was so quiet, so easygoing, so soft-spoken, the opposite of Dee’s father.” Jackie was born a year later, when Priscilla was nineteen, and Andrea was born three years after that. Jack had a good used-car business in Fort Worth and was a member of the Petroleum Club and Ridglea Country Club. For the first time in her life, Priscilla had a maid who came in three days a week. Jack Wilborn liked to play a spot of gin rummy with the boys down at the Petroleum Club and Priscilla decided to take up tennis. It was on the courts at Ridglea that she first met Cullen Davis, who was involved in a heated game with his wife Sandra. “My girl friend and I were sort of batting the ball around and Cullen asked us if we’d like to play some doubles.” In the presence of his wife—soon to be ex-wife—Cullen made a pass at Priscilla, or that was her impression. By chance, Priscilla ran into him again the following day at the Colonial golf tournament. Cullen left the day after Colonial for an international air show in Paris, and while he was abroad Sandra filed for divorce. Priscilla and Jack Wilborn were also about to get a divorce. Some weeks later Priscilla telephoned Cullen and asked if he could locate tickets to the Cowboys-Packers preseason game. Cullen couldn’t get the tickets, but he got the message: the next time, Cullen telephoned Priscilla. They arranged to have dinner.

Jack Wilborn may have been a good old boy, but his mama didn’t raise a dummy: he knew what was going on, and he made certain Sandra Davis did, too. Cullen took Priscilla to Acapulco for New Year’s Eve, and the following night, while they slept in the Green Oaks Inn in Fort Worth, Wilborn’s team of private investigators kicked down the door, sprayed the room with Mace, and took a lot of incriminating pictures. Jack Wilborn and Sandra Davis eyewitnessed the scene. Jack got everything in the divorce settlement, including custody of the three children. Priscilla got Cullen Davis, a handsome, intelligent, enormously wealthy man fifteen years younger than Jack Wilborn.

“In my eyes Cullen was a celebrity,” Priscilla recalled. “I didn’t have any concept of his wealth and didn’t care. I thought we had really found it. He was my dream come true. Of course the money didn’t hurt. What’s the saying? ‘I’ve been poor and I’ve been rich and believe me, rich is better?’ It’s like, winning isn’t everything, but losing is nothing.”

Cullen Davis and Priscilla Wilborn were married August 29, 1968, the same day that Cullen’s father, Kenneth W. Davis, Sr., founder of the empire, died in the old family home on Rivercrest Drive. There has naturally been considerable speculation over this coincidence. All three of Kenneth Davis, Sr.’s heirs—Kenneth, Jr., the oldest; Cullen, the middle son; and William, the youngest—were single when the old man died. Fort Worth gossip has it that the old man’s will specified that whichever son was married at the time of his death would inherit the family home on Rivercrest. If this were true—and it is not—there would have been a strategic value to the marriage. According to the actual terms of the will, Kenneth, Cullen, and William each inherited “an undivided” one-third of the empire. There was nothing in the will about the home on Rivercrest, but it had a clear symbolic value: the son who occupied it would have the edge among equals. In fact, the old man had been an invalid for at least three years, and his death at age 72 was imminent. “I don’t know why people try to make so much out of it,” Priscilla said. “The marriage was all planned. I had bought my dress from Neimans, we had ordered the flowers, reserved the chapel, leased an apartment. Bill [Cullen’s younger brother] and Mitzi [his girlfriend at the time] were going to be our witnesses. Cullen was on his way to pick me up when we got the call that Mr. Davis had died.” Another rumor had it that the old man had threatened to disinherit Cullen if he married Priscilla, but considering the old man’s health it seems doubtful he even knew of her existence. They certainly never met. Nevertheless, Cullen and Priscilla did move into the Rivercrest estate a few days later. It was not long after that when Cullen made the decision to build his own mansion on the 181 acres known as “the Old Davis Farm,” the estate the old man had always wanted to build but never did. Bill and Mitzi, who would marry later, now occupy the Rivercrest home, but that’s another story. Whatever happens now to Cullen Davis, the old man’s “undivided” empire is hopelessly shattered.

With the exception of the three brothers and a few trusted executives, no one knew the true depth and reach of Kendavis Industries, the umbrella company the old man had formed to oversee his empire. The conglomerate included more than eighty corporations doing business throughout North America, South America, and Europe. Walter Strittmatter, a vice president for Kendavis Industries, conservatively estimated assets “in excess” of $300 million, but others have placed the figure at closer to $1 billion. Five years after that fated day in August when the old man died and Cullen took Priscilla as his wife, Kenneth and Cullen would squeeze their younger brother out of the triumvirate, or so William claimed in a suit filed in federal court. More of that later. The point here is that when Cullen married Priscilla he was certainly in a position to indulge his proclivities.

Priscilla remembers that she spent the first year “shopping and traveling all over the world.” Cullen had always enjoyed globe hopping, and now he liked traveling with Priscilla on his arm. On the spur of the moment he might whisk her off to Rome or Paris or Caracas or Rio de Janeiro. Cullen had already commissioned architect Albert Komatsu to design the rambling, contemporary mansion on the city’s near southwest side, and as they traveled to the markets of the world Cullen began to collect art and antiques. Once, when an airline misplaced their luggage, Cullen made an instant decision to purchase his own Learjet. Friends noticed the change in Cullen. He seemed more decisive, much more his own man. And yet, as a close friend explained, “he seemed to get his kicks from Priscilla instead of from himself. Cullen didn’t like being in the spotlight, but he liked turning it on.”

Priscilla recalled: “We met important people all over the world. One year we stood right there in the VIP section, right next to President Nixon and his daughters, watching Apollo 11 take off. I think that same day we had lunch with the president of General Motors and his wife—Ed and Dolly something.”

Priscilla couldn’t pinpoint the exact moment when Cullen’s ardor began to cool, but it seemed to coincide with the power struggle among the brothers. That would have been about 1972, roughly the time Cullen and Priscilla were moving into the mansion. She would testify later to the periodic beatings, the snubs, the temper tantrums, the growing impatience, the inexplicable chill in their love life. “He made me feel like I was being too aggressive, which was exactly the quality in me he used to love,” Priscilla complained. “He’d pick a fight for the slightest reason. I’ll never forget my shock one night when he shouted: ‘Can’t you keep your damn hands off me!’ ” There was a night in Palm Springs in 1972 when she claims Cullen “beat and kicked me until I was black and blue.” At Cullen’s bond hearing Priscilla testified this occurred after she accused Cullen of flirting with another woman. Priscilla would tell of the time in 1973, just after she had broken her ankle skiing, when Cullen beat her with her own crutch. Or the time in Marina Del Ray when he broke her collarbone, or the night he knocked her across the pool table in the mansion and broke her nose, or the time in Aspen when he slapped Dee across the room, or the night he slammed Dee’s kitten against the kitchen floor until it was dead. One would suppose Priscilla would tell him to go convert his millions to broiling pennies and stuff them, that she’d had enough, but according to her version it was Cullen who first mentioned a divorce, after confessing he had had relations with other women. The final straw, again according to Priscilla, was when Cullen locked up all her jewelry in his office at Mid-Continent Supply Company.

“I called him and said I would be there in fifteen minutes and he better have that jewelry waiting,” Priscilla said. “He met me at the door with the jewelry in the envelope. We rode down the elevator together and this time I brought up the subject of divorce. Cullen said: ‘OK, I’ve been there before.’ I said, ‘Oh no you haven’t!’ ” Priscilla wrote a $1,500 check on her Master Charge and marched to the office of a good divorce lawyer. This was July 1974, almost exactly two years before the murders and not quite six after Cullen had Priscilla sign an antenuptial agreement, which she understood to be a minor document dealing with company tax matters. The details of the document have not been made public, but the contents are central to the divorce proceedings and will doubtless come up in the murder trial. Whatever the document sets forth, it has so far not seemed to inhibit judicial rulings in Priscilla’s favor. She obtained custody of the mansion and all its furnishings, a Lincoln Continental Mark IV, and monthly support payments that would escalate as the suit dragged on. Priscilla also got custody of Dee, whom Cullen had adopted (Andrea had gone back to live with her father at the time). Judge Eidson issued a restraining order prohibiting Cullen from visiting the mansion; this order would later become pivotal in the district attorney’s decision to file capital murder charges.

Judge Eidson also ordered that the estranged couple’s assets be frozen until they had agreed on a settlement. Here was a squeeze unlike any Cullen Davis had felt in his life. On November 8, 1974, just before William Davis filed his own federal suit, Cullen petitioned Judge Eidson’s court for permission to sell 44,930 shares of his Western Drilling Company stock for $1,403,163, citing as his reasons a national “credit crunch” and short-term loans to various banks in the total of $14 million. The judge refused. Instead, he ordered Cullen to increase his monthly support payments to Priscilla from $2500 to $3500. In December 1974, the judge made Cullen cough up another $18,500 “advance on community property for trial expenses”—Priscilla had asked for $50,000. Subsequent hearings in Judge Eidson’s court became increasingly bitter, as first one party, and then the other were granted postponements. Last July 30, the judge increased support payments to $5,000 a month and agreed to consider Priscilla’s request for an additional $52,000 for expenses and attorneys’ fees. The judge was still mulling this request two days later when Stan Farr and Andrea were murdered and Priscilla was wounded.

Kenneth W. Davis, Sr., known unaffectionately as Stinky Davis, raised his three sons to be frugal, diligent, hard-nosed business types. He damn well dared them to step away from a fight, the consequence being that they would have to answer to him. Kenneth and Cullen were sent to Texas A&M because, as a family friend put it, “it was the cheapest, hardest place he could think of.” Born near Johnstown, Pennsylvania, in 1895, Stinky was a classic example of the hardscrabble hustler pulling himself up by the seat of his pants. He played semi-pro baseball, flew for the U.S. Army Air Service in World War I, taught flying, worked in a steel mill, and hawked real estate. Following the oil boom to Texas in the twenties, he worked first as a roughneck, then as a clerk in an oil field supply store. In 1929 he came to Fort Worth as vice president of the tiny, struggling Mid-Continent Supply Company. Within a year he owned controlling interest. Mid-Continent had four employees when Stinky took over: at the time of his death the empire extended to six continents. Stinky was an early advocate of diversification—in 1936 he bought Great Western Drilling Company, and in 1951 he bought Loffland Brothers, the world’s largest drilling contracting firm. By the time he founded the umbrella company known as Kendavis Industries International in 1958, he owned at least fifty affiliated companies. Owned them outright, down to the last rig and paperclip.

Stinky Davis was a peer, though apparently not a friend, of Sid Richardson and Amon Carter, Sr. He was neither political nor social, and he had a near phobia about publicity. Though he maintained token memberships in all the right clubs and made some significant charitable contributions, such as the planetarium at the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History and a Girl Scout camp, there were only a handful of men who knew him, except by reputation. There is not even a special file on Stinky Davis in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram reference room—I could locate only three small clippings, one of them his obituary. A two-paragraph item in 1949 shed some light on his character. It was an article about Stinky successfully defending his horseshoe-pitching championship at the annual Exchange Club picnic. When asked to what he attributed his skill at horseshoes, Stinky said he always relaxed in his hammock at his Eagle Mountain Lake retreat for an hour prior to the tournament and he pitched his first horseshoe with his eyes closed. “That first horseshoe is usually a ringer,” he said, “and it has the desired effect on your opponent.”

A longtime acquaintance tells of an important international business meeting in New York, arranged by the State Department to negotiate a multimillion-dollar oil deal with the government of Venezuela. “It was a very touchy diplomatic situation in which the State Department was attempting to persuade Loffland to grant Venezuela credit for the drilling operation. Before they could even get around to the protocol of formal introductions, Stinky slammed his fist on the table and demanded three million dollars up front, otherwise Loffland wouldn’t move its rigs a single inch. The Ambassador from Venezuela turned the color of a chili pepper, and the guy from State said: ‘Mr. Davis, don’t you realize you’re dealing with the government of Venezuela?’ Stinky said: ‘You damn right I do! That’s why I want three million up front!’ ”

In the tradition of great tyrants, Stinky indulged his idiosyncrasies with a vengeance. Mid-Continent employees who wore taps on their shoes or green neckties were summarily dismissed. Attendance at the annual company picnic was compulsory. A former employee who edited the company newspaper said: “It was true that the old man hated publicity, but there was a standing rule that his picture had to appear on every page of the company paper.” Stinky consciously fostered a fierce sense of competition among his three sons, assigning them menial tasks and then personally inspecting the job in the manner of a drill instructor with white gloves. A family friend recalled: “Stinky would tell the boys, ‘Go down to the lake and repair that old piling. When you get done, I’ll come down and show you how it should have been done.’ ” Cullen was the quietest and least personable of the sons—“the weak one,” some said, not exactly supine but painfully uncertain of himself—and yet it was Cullen who most enjoyed emulating the old man and passed down Stinky’s words of wisdom and tales of obstinacy. A favorite story of Cullen’s concerned the time Amon Carter approached Stinky on behalf of some pet civic project. Stinky refused for the pure pleasure of refusal, and when Amon let it be known that Fort Worth wouldn’t look kindly on this sort of pettiness, Stinky is reported to have cackled: “Tell you what, Amon. You take Fort Worth and I’ll take the rest of the world.”

“In one way Cullen was just like the old man,” a friend said. “Both of them were tight as Dick’s hatband. When Cullen got his first car, a Chevy Powerglide—that must have been Christmas of our senior year at Arlington Heights—he’d charge us a nickel to ride to the pool hall.” In high school and in college, Cullen was so withdrawn that if it hadn’t been for his family money, few of his classmates would have remembered him a day after graduation. He liked to shoot pool and play shuffleboard and hang out at the ice cream parlor, but he participated in no organized sports or school activities, caused no trouble, and contributed nothing to the general weal. Cullen was never much of a drinker or a womanizer (at least before Priscilla), and except for token $5 wagers on pool games he did not gamble. Until he met Priscilla, Cullen drove an old Pontiac and dressed in the style of a young executive applying for his first job at the bank. Even in high school he frequently wore suits and ties. There was a formality about him that suggested he probably slept in freshly pressed pajamas, buttoned to the neck. Even the old man complained that Cullen “dressed like some kinda popinjay” and ordered his son several sports coats, which Cullen apparently never got around to wearing. Priscilla was constantly after him to dress more casually. “I never got him into jeans, of course, but I did buy a conservative leather sports jacket that he wore occasionally,” she said. “Later, I bought him a beautiful leather suit, but he couldn’t handle that.” If there’s such a thing as being conspicuously inconspicuous, that was Cullen Davis. A regular at the Rangoon Racquet Club, one of the fashionable bistros that have attempted to expand Fort Worth’s limited horizon in recent months, recalled: “Cullen would usually come in alone and sit at the corner of the bar. He would appear very proper, very correct in his conservative haircut, pinstripe suit, and wingtip shoes. If you didn’t know he had all that money you’d figure him for a vice president of Chicago Pneumatic having a nightcap before taking it back to Green Oaks for some sleep.”

In his business and private life Cullen was stern, highly disciplined, intolerant of mistakes or failure. Like his old man, he was absolute master of his household. Dinner was served at the appointed time, or it wasn’t served. Once, when Priscilla and her three children were a few minutes late to the airfield where the Learjet was waiting to take the family on a holiday to Aspen, Cullen ordered the pilot to take off without them. At Cullen’s insistence, Priscilla and the two girls learned to play chess.

At other times, though, his patience seemed limitless. Once he kept Andrea awake half the night forcing her to memorize a math lesson, and his despair at the girl’s inability to master the subject seemed genuine. “I tried to tell him that Andrea was a slow learner, a dreamer, a girl with artistic instincts,” Priscilla said. After the hard night’s math lesson, Andrea arranged to visit her father, Jack Wilborn, and when she didn’t return for dinner that night Cullen unleashed his fury. Both Priscilla and Dee recalled that Cullen telephoned Andrea and issued his ultimatum: either she would return to the mansion at once or be forever barred from its walls. “He told her she’d have to give back everything,” Dee said. Dee was more of a disciplinary problem than her younger sister. A year or so after the incident with the kitten, Cullen again slapped Dee and she ran away. The authorities located her, and when a social welfare worker asked Cullen what he planned to do, he said point-blank that it was his intention to “take her home and beat her severely.”

Only rarely did Cullen display his temper publicly. The most commonly cited incident occurred six or seven years ago at the Steeplechase Ball. A Fort Worth attorney who was there told the story: “It was raining like hell and the parking attendants were having a bad time getting all the cars up to the clubhouse entrance. Cullen got it in his head they were taking too long getting his car so he grabbed the whole board of keys from the attendant’s booth and threw them in the mud. A lot of very prominent folks went home in taxicabs that night.” On most occasions, however, Cullen’s public demeanor was flawless. He loved to entertain and delighted in planning each detail. On Sundays when the Cowboys were playing at home Cullen would invite his select group to his private box at Texas Stadium, arrange the transportation and the refreshments, and make dinner reservations for after the game. On these occasions Priscilla always played her role—“rich bitch.”

Mrs. Cullen Davis: even those socialites who regarded Cullen as a prig and a boor choked on the name. “I wouldn’t be caught dead walking down the same hall with her,” sniffed the wife of a prominent attorney. The thing I liked most about Priscilla was that she didn’t care; and for a while, at least, neither did Cullen. Priscilla wasn’t malevolent about her indifference to what people thought of her; it was just that Cullen and his crowd bored her. She was a good sport about it; she could play the role so long as no one asked her to take it seriously. There’s a story of a night in a Dallas restaurant when, without warning, she unzipped Cullen’s pants and complimented his manhood. Priscilla denied this, though she acknowledged that Cullen always encouraged her to “be aggressive.” Whatever the truth, this was a side of her that Cullen seemed to enjoy, at least in the early years of their marriage. With Priscilla on his arm, Cullen became a fixture at night spots like the Rangoon Racquet Club and the Old San Francisco Saloon and the Round Up Inn. They began to skip the Steeplechase Ball and go skiing instead. Cullen found reasons to leave his office early. He started his first suntan. While Priscilla paraded around the Colonial golf course in her hip-hugger jeans, Cullen showed porno movies in a rented trailer on the country club parking lot.

But it was the mansion that took center stage. It became a showplace the likes of which Fort Worth had not seen since the days of the cattle barons. The edifice itself somehow managed to suggest at once the past and the future, Giant and 2001, without really being representative of either. For all its ultra-modern pretense, there was something in its chalk-white strength that suggested the Middle Ages, a Moorish fortress perhaps, a permanency and force that went beyond flesh and blood. It was a monument, all right, but when you studied it at length the mansion appeared to celebrate not a perfect marriage but Cullen Davis. Yet as such it was a stupendous malaprop; it seemed so out of character. Sue Smith, whose property backs up to the estate, recalled her astonishment the one and only time she met her neighbor: “It was so hard to connect this man with this place. Cullen Davis struck me as . . . I don’t know exactly . . . it was like talking to a man who had worked very hard to overcome a speech impediment.”

It was hardly the place Stinky would have built, and maybe that was the point. In retrospect Fort Worth society might turn up its nose, but the mansion became a stage on which the elite would act out their chosen roles: charity balls, Opera Association teas, hot-air balloon extravaganzas; not mere parties, spectacles. To some, though not all, of Fort Worth’s upper crust, an invitation to the Davis place was a perverse rite, comparable perhaps to being allowed to peruse King Farouk’s porno collection. To others it was tantamount to devil worship. God knew what went on up there, and presumably God’s wrath would correct it. On one thing nearly everyone agreed: Priscilla went with the place.

Cullen was a knowledgeable collector of antiques and art. He had a decided preference for nineteenth-century European painters, and he personally sought out and bargained for each work that hung in the mansion. But when you enter the living room, it is not the two Dufys or the silver showcase of jade and ivory carvings and precious stones that snap you about; it’s the brilliantly lighted six-by-eight portrait of Cullen and Priscilla that dominates the great north wall. Cullen is portrayed in his dark business suit, seated primly with his chairman-of-the-board bearing and dry ice smile. He is the dominant personality; Priscilla is pictured suspended in space, her long platinum hair falling over her shoulders, and a maximum of her breasts and thighs showing under her micro-mini. She reminds you of a blonde Raquel Welch in One Million Years BC. In the background are ghost images of the master and mistress—of Cullen shooting pool, Cullen with his skis, Cullen in his tennis togs; the ghost images of Priscilla are more Raquel Welch poses in gowns and short leather skirts. A European friend looking at the painting remarked to Priscilla, “You look like something else Cullen did.”

Even as Cullen and Priscilla were moving from the old family home on Rivercrest and into their mansion, a power struggle was becoming evident to those at the highest levels of Kendavis Industries. Either Stinky Davis had a perverse sense of human drama, or he really did believe his empire could be cut in thirds and still remain “undivided.” According to the “weak link” theory, Cullen was destined to be the swing man. Like the divorce and the murder, the power play at Kendavis was a legal complexity, but it was William Davis’ contention that (1) Kenneth, Jr., and Cullen joined forces to squeeze him out, and (2) Cullen’s “reckless, extravagant, and wasteful” personal spending habits were endangering the empire itself. Documents filed in connection with the suit claimed that by November of 1974 (four months after Priscilla filed her papers) Cullen had accumulated personal debts of about $16 million and business debts in excess of $150 million. The suit alleged that Cullen then manipulated the companies under his personal control (Stratoflex, Inc., and Cummins Sales & Service, Inc.) to cover personal debts, and moreover, that both Kenneth and Cullen had manipulated Stratoflex stock to minimize their income taxes.

The day after Priscilla filed for divorce, Cullen moved into a suite at the Ramada Inn Central. Priscilla visited him there on three occasions—once, when she came to ask for a new Mark IV, they had dinner, watched a Cowboy game on TV, and made love—but the perfect marriage had ended. Cullen would shortly have a new girl friend, Karen Master. The following February, Priscilla would take up with Stan Farr. William Davis’ law suit would continue to trickle through its maze of legal dodges and corporate flimflam, and the divorce suit would bog down on such petty details as who paid the children’s country club bills and Priscilla’s long-distance phone charges. Kenneth Davis, Jr., who for some years had lived in Tulsa and commanded that cornerstone of the empire known as Great Western, would spend much more time at the home office in the Mid-Continent Building.

Early on the morning of August 3, after the bodies had been removed from the mansion, Ken Davis telephoned Cullen at Karen Master’s house and asked if he had heard about the shootings. Ken testified that Cullen replied, “No, who got shot?” Ken told him and then inquired what Cullen had been doing. Cullen said he had been in bed. When Ken told Cullen that the police were looking for him, there was no response.

“What are you gonna do?” Ken asked his brother, and Cullen replied: “Well, I guess I’ll go back to bed.”

As for William Davis, he telephoned the sheriff and asked that a patrol car be dispatched to guard his home, then he loaded his shotgun and herded his family into the attic.

Fort Worth was just Stan Farr’s kind of town. A bawdy town bent to accommodate, a town on the make, a town that smelled of old oil and tobacco juice, of abandoned stockyards and packing plants that continued to smoulder long after the fire was out, a town on the edge of a vanishing frontier where people still met socially at the rodeo and the stakes were always high enough to make it interesting, a town where the social climate was so frosty and the structure so inbred and inhibited that upward mobility was hardly more than a diversion. It was a town large enough to support the hustle and small enough to sustain the gossip. Downtown Fort Worth was simultaneously crumbling and rebuilding. The old Westbrook hotel, where many an oil swindle set the tone for its times, was boarded up for good, and the once great department stores like Leonards, Stripling’s, and Monnig’s sat fading and flaking like hags cadging coins on the sidewalk. And yet, in the shadows of what had been the Leonard Brothers complex, the Tandy Corporation was erecting an enormous new world headquarters.

TCU was Fort Worth’s kind of school; it had a tough exterior and a soft underbelly, and no matter how poorly the basketball team fared, the Frog Club was there for support. It was the kind of school where students wore Levis and tight T-shirts before they were the fashion, a place where men were still judged on how much beer they could drink and how loud they could belch.

Stan Farr had met Cullen and Priscilla Davis on a couple of occasions, a quicky introduction at the Round Up Inn during rodeo week, a nod from across the room at Western Hills. At six-feet-nine, Stan Farr was a hard man to overlook. He had been a fair basketball player at TCU in the late sixties, and an ex-jock was something special, but more than anything else it was his size and his easygoing overgrown bear cub manner that made him such an attraction. “His size was his birthright, something he had been forced to learn to live with,” said Billy Gammon, an Austin insurance agent who roomed with Farr at TCU. Stan’s older sister, Lynda Arnold, who later became one of Priscilla’s closest friends, explained: “He shot up like a bean pole his first year in high school in Texarkana. At first it embarrassed him. He got into basketball almost in self-defense. People would come up and say, ‘Hey, boy, you oughta be playing ball,’ so he decided to do it.”

Stan’s father, Lynn Farr, Sr., had played football at East Texas State and worked as a bit player in Hollywood westerns back in the forties, but his movie career didn’t work out, so he returned to Texas and got into the construction business. An older brother, Lynn, Jr., was Texas Golden Gloves heavyweight champion in 1965: he went to the nationals where Jerry Quarry broke his jaw with the first punch. There has been that star-crossed pattern in the lives of the Farr family. After college, Stan operated a variety of businesses—a pizza house, a swank supper club, a topless hamburger joint. They all went bad. Stan moved to Kansas City and worked for a brewery. He married for the second time (his first was a brief marriage in high school), then returned to Clifton, sixty miles south of Fort Worth, to join his father and younger brother Paul in the construction business. Four years ago Paul was killed in a car wreck. “The business just seemed to fall apart after Paul was killed,” Lynda explained. Stan got into another construction venture where a man from Dallas stiffed him. Billy Gammon said: “It was typical of Stan’s luck that he got into the quick apartment-complex game ten months after the fire went out.” Lynda added: “My brother was the all-time nice guy, but he was amazingly gullible. Right up to the end, people he trusted were still doing a number on him.”

“Stan always had an eye for the rich ladies,” Billy Gammon recalled. “He always had one full-time mama, and invariably she was well-heeled. Subconsciously, he seemed attracted to the tough types, the ones who would give him hell. One sorority girl in particular—they checked into a motel and as soon as Stan disappeared into the bathroom, she split with his car. The next day he was with her again, just like nothing had happened. He wanted to be big time. He wanted the appearance as much as the security.”

When Billy Gammon read about the murder, the first thing that flashed through his mind was a game they used to play in college. Stan had a habit of grabbing Billy and pressing him to the ceiling. One day Billy bought a gun. The next time Stan came for him, Billy jokingly threatened to fill him full of holes. Stan loved it. He’d beg Billy’s forgiveness, then, according to the way their game developed, Billy would pretend to shoot him anyway. Stan would act out a marvelous dying scene, gasping and spinning about and finally collapsing in the kitchen with a freshly opened beer in his hand.

“The story in the paper said that the killer dragged Stan from the foot of the stairs to the kitchen,” Billy said. “Maybe he did, but that’s very hard to imagine. I kept seeing Stan saying: ‘This isn’t really happening,’ while he staggered toward the refrigerator in some other man’s kitchen. The last picture I saw was them loading him into the meat wagon. All you could see were those size sixteens sticking out under the blanket. I thought, yeah, that would be the way it ended. It could have been some tumble-down shack on White Settlement Road, but that’s how it had to end.”

In January 1975, while his own divorce was moving through the courts, Stan moved to Arlington to live with his sister. Lynda was precisely the kind of sister Stan would adore, big and outgoing, the ex-wife of a Fort Worth disc jockey, a thinking woman who always had some pots boiling. By that time Lynda Arnold had her own thriving business, the Fun Factory, an organization that specialized in pepping up convention parties and tired company picnics. About a month after he moved to Arlington, Stan ran into Priscilla at the Round Up Inn on the rodeo grounds. “They started dating fairly regularly,” Lynda said. “Little by little, Stan’s clothes were disappearing from my house.” By summer Stan had moved into Cullen Davis’ mansion. He grew a beard and exchanged his customary business suit for cosmic cowboy wear. A new business venture came his way, a pseudo-western discotheque called the Rhinestone Cowboy, on Camp Bowie Boulevard across from the Old San Francisco Saloon. That, too, would come to nothing: on the day that he was killed, Stan Farr had dissolved his partnership at the Rhinestone Cowboy and was putting together a new group to buy old Panther Hall, Fort Worth’s cradle of country music. That night he and Priscilla talked about getting the club business out of his system. He had a hankering to get back into construction, but Priscilla encouraged him to enter politics. She thought county commissioner would be good for openers.

“We were slow to realize that we loved each other,” Priscilla said. “Gradually, we began to talk about marriage, and building our own place. Stan never felt comfortable here. He was like a big kid, so gentle, so even-tempered and compassionate. He could handle the toughest situation with a few soft words. Going out with Stan was a three-ring circus. Being married to a celebrity like Cullen, I naturally attracted a lot of attention. Being with Stan took the limelight off of me, which I enjoyed. Stan and I had an agreement that when we went into a place we wouldn’t separate. Otherwise the men would attack me and the girls would attack him.”

By now Cullen and Priscilla’s divorce struggle had been going on for nearly two years. Cullen had pretty well moved in with Karen Master, and they were an item at all the old night spots. Karen Master seemed to have a calming effect on Cullen. “He seemed much happier, much more settled down in a harmonious family routine,” said Hershel Payne, an attorney who handled various civil affairs for Cullen. “Karen has a deaf child, and Cullen had become active in the charity for deaf children.” Others observed how much flashier Karen Master had appeared since she met Cullen—you couldn’t help notice the striking resemblance to Priscilla.

Inevitably, Cullen and Karen would have to cross paths with Stan and Priscilla. It happened at the Old San Francisco Saloon. It was like a scene out of a western: Cullen walked over, smiled at Priscilla and said: “What’s a nice girl like you doing in a place like this?” Then he turned to Stan Farr, who looked even larger than he was in his Hoss cowboy hat and boots and the genuine bearclaw belt buckle Priscilla had given him. “Bob Lilly is looking for you,” Cullen joked with his customary straight face. Cullen introduced Karen, then they went separate ways, but it was all amiable, and when they met again a week or so later, it was all still amiable.

As summer approached and Fort Worth society played out its ritual of debutante functions, charity balls, golf tournaments, graduations, and reunions, gossip heated up. The new police chief was making it tough for an ordinary citizen to leave a night spot and drive away in his own car, and District Attorney Tim Curry had let it be understood that laws prohibiting gambling paraphernalia would be strictly enforced. The feeling that something had to give became shocking reality when police raided the annual Fort Worth Opera Association’s fund-raising gala, seizing crap tables, roulette wheels, and bejeweled patrons of the arts. The Cullen Davis divorce case bubbled just below the surface. If Priscilla would compromise her demands, the divorce could become final on July 30 and a lot of bankers with a lot of funny paper would breathe easier. “I predicted that either he would kill her or she would kill him,” socialite Billie Wright Parker would say later. “Priscilla sat right at that table [at the Rangoon Racquet Club] and told everyone in the place she was going to get the house and three million dollars.” Cullen and Karen were planning a trip to Venezuela, but the thing that most occupied Cullen’s mind was his twenty-fifth high school class reunion. A few nights before the reunion there was another meeting at Dee’s high school graduation. Stan stuck out his hand and Cullen wheeled about and walked away in an icy snit. Cullen had arranged a series of dinner dates with some old classmates and his moods varied from ebullient to hostile to egomaniacal. Three times he telephoned the wife of a former classmate, who coincidentally used to be Bill Davis’ girl friend, reminding her not to forget to bring the old high school yearbook.

Arlington Heights grad Tommy Thompson, whose book Blood and Money chronicled the inner workings of murder and high society in Houston, was the main speaker at the class reunion. They talked about those who had made it and those who had failed and those who had died along the way. They gave out the usual cornball awards to the fattest, the baldest, the grayest. Cullen Davis accepted the “playboy” award and thanked them “on behalf of my ex-wife, my present wife, and my girl friend.” Later, as Cullen and his group dined at the Carriage House, Cullen seemed obsessed with the high school yearbook.

The woman who had brought the yearbook recalled: “Karen was very excited about the trip to Venezuela. It was her first trip abroad, and she was showing off her passport and talking about our own Learjet and how wonderful it all was. For some reason Cullen became very abrasive. Karen started crying and ran out to the car. Cullen seemed mesmerized by the yearbook. He told the story about one of their classmates who had been indicted (and acquitted) for killing a woman friend and attempting to burn down a house to hide the body. We all listened for a while, then someone tried to change the subject, but Cullen kept coming back to it . . . over and over until we were all ready to cry.”

The following night they had dinner at the Merrimac where Cullen told dirty jokes in Spanish and talked about oil depletion. In fifteen years, he predicted, oil would be completely depleted: for that reason, he rambled on, he had just added an eightieth company to his conglomerate. A friend who was there recalled, “Right in the middle of his story he turned to some stranger at the next table and said ‘I heard that. How would you like to step outside?’ I couldn’t believe my ears.” Cullen insisted on ordering the wine. The scene that followed put a full damper on the reunion. The friend went on: “We were all joking, saying how about a nice bottle of Thunderbird, Cullen, but when this young waiter came over Cullen ordered what he called his private stock. It was some name with about seventeen syllables. He repeated it twice, but the poor guy couldn’t understand what he was saying. Finally he shouted, ‘Goddamn it, do I have to write it for you?’ He ordered the maitre d’ over to our table and dressed him down and said he didn’t ever want to find less than eight bottles of his private stock on hand.”

Tongues wagged, too, about the goings-on up at the mansion. Singer B.J. Thomas and musicians such as Rusty Wier had become tight with Stan and Priscilla, and the mansion became a haven for pickers, groupies, and night prowlers. In the minds of some, that had to mean drugs and free sex: Fort Worth’s definition of an orgy is a light burning after midnight. If you knew Priscilla Davis, you would know that drugs and group sex are not her bag; by reasonably liberal standards she would be considered something of a bluenose.

“I knew all about those wild stories,” she said. “Stan and I decided to quit inviting musicians over. I remember being backstage at Willie’s picnic watching all those awful groupies. I resented them. I resented people thinking I was one. Those musicians all had beautiful wives, how could they go for those awful things? They couldn’t be any good in bed. I’d look at those awful groupies gooned out on quaas and think: ‘Well, I guess that’s about as close as they’ll ever come to being somebody.’ Me, I don’t need it. After you’ve been with the President of the United States, you’re not gonna be turned on by a few musicians.”

We come now to the tricky part, August 2, the date on which Cullen Davis is alleged to have shot four people, two of them for keeps. I say tricky, because Cullen Davis must be presumed innocent until and unless his trial shows otherwise. His attorney declined the opportunity to be interviewed for this story, so what follows is a composite of my own interviews with other parties and testimony from court records.

The divorce hearing on July 30 had only reinforced the stalemate. Ken Davis testified that Cullen was “upset” when the judge increased support payments, and Ken agreed with his brother that Priscilla was “unfair.” July 30 was Priscilla’s thirty-fifth birthday, but friends reported that “she was very depressed, very down.” In his easygoing manner, Stan Farr was dissolving his partnership at the Rhinestone Cowboy. Dee had driven to Houston to pick up Andrea, who was attending the same vacation Bible school Priscilla had attended as a teenager. On the afternoon of August 2, Cullen invited Dee to lunch. They talked about her plans for college and Cullen asked her to go back to the mansion that night and prepare a budget. Instead, Dee went to a party. Bubba Gavrel, Jr., had a date with Bev Bass, who planned to spend the night with Dee. Cullen’s activities are sketchy, but a parking lot attendant at the APCOA garage testified that Cullen left his Cadillac at the garage and drove away instead in a company pickup truck. That was at 5:30 p.m. Thirty minutes later, according to a security guard at the Mid-Continent, Cullen entered the building and stayed until 7:50 p.m.

Around 9 p.m. Stan and Priscilla left the mansion to meet some friends for dinner. Priscilla personally activated the elaborate security system before they drove away in Stan’s Thunderbird: a panel of lights on the wall near the front door showed that all doors and windows were locked. Andrea was alone in the mansion at least as late as 10:30 p.m. when she talked on the telephone to Lynda Arnold and Lynda’s fourteen-year-old daughter, Dana. After dinner, Stan, Priscilla, and their party stopped for drinks at the Rangoon Racquet Club, where, by chance, they ran into Bubba Gavrel and Bev Bass. Bev did not mention her plans to spend the night at the mansion. It was shortly after midnight when Stan and Priscilla returned to the mansion and Priscilla noticed the telltale lights on the security panel.

In the bond hearing a few weeks after the murders, Priscilla testified:

“Cullen stepped out from the direction of the laundry room. He was dressed all in black. His hands were inside a black plastic bag and he had on a shoulder-length curly black wig, like a wig that hadn’t been set. He said, ‘Hi,’ . . . and then he shot me. I felt the blood and the big hole in my chest. I screamed to Stan, ‘I’ve been shot! Cullen shot me! Stan, go back!’ But I could hear Stan coming downstairs. I saw Stan holding the door at the bottom of the stairs, he was holding it from the inside and Cullen was pushing it from the outside. Cullen fired through the door and I heard Stan cry out. Then Cullen pushed the door open. Stan grabbed him and they wrestled around and then Cullen jerked back and fired again. Stan turned and fell and he was looking at me. He was kind of on his side with his chin up. Cullen stood at Stan’s feet and shot him two more times. Then Stan just kind of laid his head down—he closed his eyes and laid his head down and died . . .”

Priscilla testified that while Cullen was preoccupied dragging Stan Farr’s body toward the kitchen, which led to the basement where Andrea’s body lay, she opened the sliding glass doors and ran into the courtyard. She tripped and fell, and when she looked up Cullen was standing over her, still holding a gun inside the plastic bag. Priscilla started screaming: “Cullen, I love you. I didn’t—I have never loved anybody else. Please, let’s talk . . .” Cullen grabbed her arm and pulled her toward the house, saying, very softly, “Come on, come on.” He pulled her back inside the mansion, then left her near the front door and returned to the kitchen where Stan Farr’s body lay. “I jerked off my shoes, wrapped my skirt tight and started running. I remember diving into some shrubs and trying to be very still.” She could see Cullen walking toward her again. Then she heard voices from the driveway. Bubba Gavrel and Bev Bass had parked near the garage and were walking toward the courtyard. She heard Bubba say: “Who is it? Who are you?” Then she heard a female voice: it was Bev Bass, but Priscilla’s first thought was “My God, it’s Dee!” Priscilla went on to testify that Cullen walked out of the courtyard gate and toward the front of the mansion, in the direction of the voices. She ran out the gate and down the slope, heard shots and kept running, across a field in the direction of a neighbor’s house. She banged on the door, screaming out her story, knocked again and rang the bell, but the neighbors refused to open the door. Finally, a voice from the house told Priscilla that they had called for an ambulance and the police. But they still refused to open the door.

Bubba Gavrel would testify that as he and Bev Bass approached the mansion they heard a woman’s voice saying “I love you” and a man’s voice answering “Come on . . . come on.” When Bubba looked over the wall into the courtyard, he saw a man dragging a woman toward the house. He and Bev walked toward the front of the house and the man followed them. Bubba asked the man what he was doing, and Bev said, “He’s stealing something.” The man said: “Come on. Let’s go inside. Come on with me.” They followed him toward the light from the front door, and that’s when Bev Bass recognized the man as Cullen Davis and called his name aloud. “When she said that,” Bubba testified, “he turned around and shot me.” Bev Bass ran back toward the parking area, and the man started after her. “I couldn’t move my legs,” Bubba testified. “I tried to get up, but my legs wouldn’t do anything.” He crawled toward the front door, the door that Priscilla and Stan had entered. It was locked. Through the glass panel at the side of the door Bubba could see blood. He crawled back into the yard, looking for a stone to break the window, then he saw the man run to the front door, fire three shots into the window and climb inside. That was the last Bubba saw of the man in black.

A few hours later, shortly after Kenneth Davis had telephoned his brother, Fort Worth police surrounded Karen Master’s house in Edgecliff. Using a bullhorn, they called for Cullen to surrender. Cullen asked for permission to get dressed, then came quietly. A day later he posted the full amount of his bond with an $80,000 cashier’s check and was freed.

On August 20, as Cullen was about to board his Learjet for a business trip to Houston, he was rearrested, charged with capital murder, and, after a five-day hearing, held without bond.

Of all the enigmas and bizarre twists in the Cullen Davis affair, the whys that time may or may not answer, the one with the most far-reaching legal ramifications may be District Attorney Tim Curry’s carefully contemplated decision to seek the death penalty. To the layman’s ears it sounds strange to hear a prosecutor speak not of the murder trial but rather “the law suit,” but in an affair such as this, where the stakes run into the millions and public passions sometimes approach the point of hallucination, the term seems painfully precise. In accordance with Texas law, a capital offense—one punishable by death—occurs when a defendant commits murder while in the course of committing another felony. There is no question that Cullen Davis was under a civil injunction prohibiting him from setting foot on the property, but when you take it another step, when you allege that Cullen Davis became a burglar upon entering the mansion, the ice gets thin.

Curry is a smart prosecutor, definitely not the hip-shooter type. He acknowledges that “there was a ton of public pressure so far as the law suit is concerned.” Assistant DA Marvin Collins, the “lawyer’s lawyer” on Curry’s staff, four other lawyers, a team of investigators, and of course the Fort Worth police sifted the evidence for fifteen days before Curry was convinced of the merits and theory of the capital charges.

“The theory in this case,” Curry told me, “is that Cullen Davis entered a habitation with the intent to commit another felony—murder. There is no dispute that it was his own house. But he was under civil injunction to not enter that property, and the question now is: was he in fact the owner? The law here is broken into three parts. An owner is, number one, the person who has title to the property; or number two, the person who has possession of the property, whether lawful or not; or number three, the person who has greater right to the possession of the property. Number three is the key to this case.”

Cullen Davis’ defense team includes some of the most brilliant and high-priced legal minds in the state—Richard “Racehorse” Haynes of Houston, Phil Burleson of Dallas, and Bill Magnussen of Fort Worth, among others. They have accused Curry of “selective prosecution” to which he replies: “They’re just saying that because something hasn’t been done before, it can’t be done.” Some legal railbirds speculate that the capital murder charges were actually a ploy designed to deny bail to Cullen Davis: defendants in capital cases are routinely held without bail. Under the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, a bail bond cannot be used as “an instrument of oppression,” which means that bail cannot be set so high that it would be financially impossible for a defendant to post bond. In Cullen Davis’ case, this provision is almost academic. Davis offered to put up everything he owns, pay expenses for two federal marshals to watch him full-time, speak at two-hour intervals with probation officers, surrender his passport, driver’s license, and credit cards, and obey any other orders the court might think of as stipulations for his bond. But all this became moot when the charge was changed to capital murder.

In a normal murder case, even a normal capital murder case, the defense would be expected to (1) seek a change of venue and (2) stall for time while passions cooled. Cullen Davis’ attorneys elected to do neither. Barring some last-minute appellate reversal which would get their man out of jail, Cullen’s lawyers are prepared to begin their defense on February 21 in Judge Tom Cave’s 213th District Court in Fort Worth. They want Cullen Davis tried in his hometown. Racehorse Haynes has already set the stage for the defense, suggesting that the murders were related to “society narcotics—coke, marijuana, and possibly heroin” and predicting that the real killer will be exposed during the trial. It doesn’t take a great legal mind to speculate that the defense intends to do everything in its power to impeach the state’s star witness, Priscilla Davis. The one big hole in the district attorney’s case, and it is enormous, is that there is no witness to the murder of Andrea Wilborn. No witness, no motive, no logic: except for the murder of Andrea Wilborn, this would be your normal murder case, and Cullen Davis would be out on bond doing business as normal. Why, folks in Fort Worth might not even take it too seriously: just another in a long series of lovers’ triangles that were blown apart with a gun. But Andrea, the innocent teenager, made it different. District Attorney Tim Curry acknowledged the unique nature of the case when he told me: “If this had happened on White Settlement Road, if it had been other people and other places, things might be different. Obviously we don’t routinely spend hundreds of man hours on a murder case . . . we obviously can’t afford it. We wouldn’t have five lawyers working on it full time, but then neither would the other side.”

Cullen Davis’ legal problems will not end with the murder trial. Attorneys representing Bubba Gavrel and those representing the family of Stan Farr have both filed $3 million suits against the multimillionaire. On December 31, 1976, attorneys for William Davis announced they were withdrawing their suit. William Davis was reported to have received a $10 million settlement. There remains the possibility that the IRS or the SEC will look into the charges of stock manipulation.

Meanwhile, life for Cullen Davis goes on as well as could be expected for a man in jail. He writes corporate memos and keeps current on the world of high finance. He corresponds with his ex-wife, Sandra Davis, who lives in Dallas with their two sons, and on at least one occasion during a hearing, Cullen had lunch with Karen Master. There is only one radio in the cell block and the prisoner who controls it, the one with the most seniority, doesn’t like football and that is a problem. As the holiday season approached, Cullen and Karen mailed Christmas cards as usual. Dee Davis got one. “Cullen still maintains his sense of humor,” says attorney Hershel Payne, who visits him almost every day. “He’s always got something pleasant or nice to say.” Cullen has a new pen pal—Hershel Payne’s twelve-year-old daughter. The sealed notes that Hershel delivers are decorated with hearts and flowers and little girl cryptograms like SMACK. Cullen seemed especially pleased with her latest report card and took pains to compliment her. Hershel Payne’s daughter was a playmate of Andrea Wilborn. Her name is also Andrea.

Editors’ note: For an update on Cullen Davis, who was acquitted of all charges, read Skip Hollandsworth’s feature from March 2000 titled “Blood Will Sell.”

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Crime

- Fort Worth