When Marion “Little Joe” Washington passed away at 75 on November 12 in Houston, with him went the last link to a vital component of the Bayou City’s rich blues heritage and a man who influenced some of the genre’s greatest talents.

When Marion “Little Joe” Washington passed away at 75 on November 12 in Houston, with him went the last link to a vital component of the Bayou City’s rich blues heritage and a man who influenced some of the genre’s greatest talents.

“The night I got the news that Joe died, I was down in Galveston and I happened to have a Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson CD with me; I didn’t have any Little Joe,” said Roger Wood, a retired professor of English at Houston Community College and the author of Down In Houston: Bayou City Blues. “After I popped it in, I was thinking, wow, I am hearing Little Joe all over this record.”

Inspired by T-Bone Walker and Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, Washington played a stinging, glassy, jazz-inflected and soul-piercing blues guitar sound. It was a style made famous by a few other Houstonians who became internationally renowned blues legends—most notably Watson, Albert Collins, and Johnny Copeland.

Those three musicians left Houston for more established recording centers and later enjoyed major successes. But some argue that Washington’s talent was equal—or greater—to theirs.

Houston blues guitarist I.J. Gosey, who first saw Washington at the second incarnation of Shady’s Playhouse, a legendary juke joint in Houston’s Third Ward, told Wood in 2005, “The others, they went farther than Little Joe with what they had, made more of themselves. But they couldn’t beat Little Joe for raw talent.”

Even Copeland, who went on to record with Stevie Ray Vaughan and enjoy a vaunted career, acknowledged his friend’s enormous influence. As he told Houston Press reporter Jim Sherman in 1996, “My music, Albert Collins’ music, Joe Hughes’ music—when you listen to any of that, you’ll hear some Little Joe.”

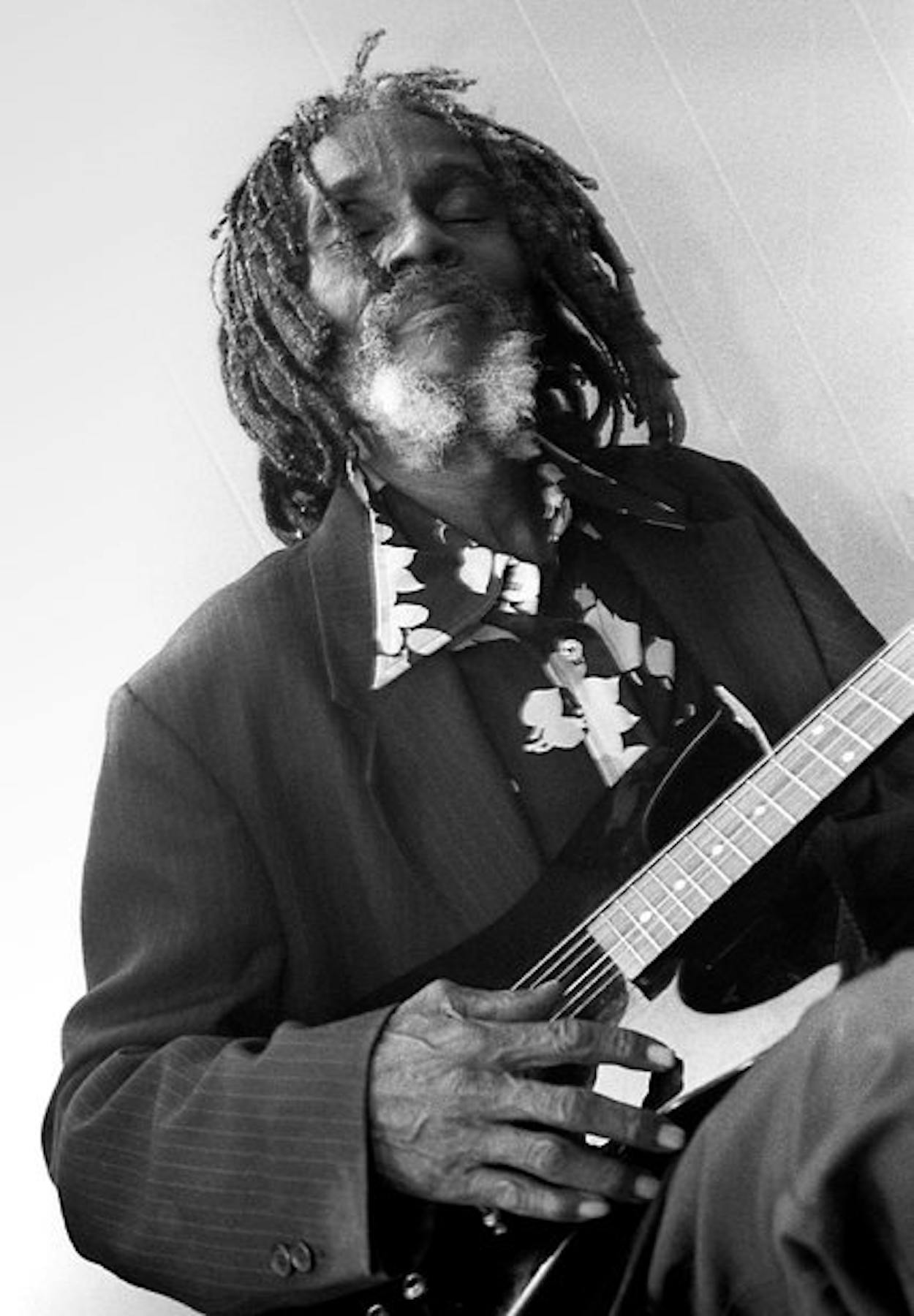

Houston was lucky to have Washington as long as it did. He was often semi-homeless, living in the tumbledown shell of his boyhood home, which lacked basic utilities and a functional roof. When that burned, he bounced around until admiring friends took him in. (Washington lived for a time in an apartment above Houston’s Continental Club.) His guitar was often in hock. He’d lost most of his teeth, and his hair was a tangle of disheveled dreadlocks, almost always tucked into a mangled wide-brimmed hat. His sole mode of transportation was one of a succession of children’s bicycles. (Washington stood about five-foot-four and was slight as an elf.)

He was born in 1939 at Houston’s Jefferson Davis Hospital. By his own account, Washington started playing the piano at five, and took formal lessons at nine or ten. He played the trumpet in the Jack Yates High School marching band, and from roughly 1958 to 1968, lived in Juarez-El Paso, gigging in rowdy joints catering to tourists and servicemen from Fort Bliss. He cut a few singles, one at the behest of (and backed by) the Champs, of “Tequila” fame, who had been amazed by one of Washington’s borderlands shows.

From 1968 and the mid-1990s, biographical details—at least as far as music goes—are scant.

And then came the comeback.

Rich Hornbuckle, co-owner of the Blue Iguana nightclub in Montrose, gave Washington a weekly gig. “He was this kind of stinky, weird-looking guy,” Hornbuckle said, “but he was so ingratiating and humorous, and then he got on the stage and just went nuts. I was transfixed. I felt like I was in a roadhouse in 1956 in God-Knows-Where, Texas. We knew we had to get him for a regular show, but ‘regular,’ for Little Joe, that was the operative phrase: we were lucky to have him show up 63 percent of the time.”

By 1998, Watson, Collins, and Copeland—all like family to Washington—had died. Washington’s old friend and mentor Joe “Guitar” Hughes followed in 2003, the same year Eddie Stout, a producer in Austin, released Washington’s full-length debut, Houston Guitar Blues.

Stout saw something in Washington nobody in Houston had the time or the wherewithal to bring out. “I just figured if he got in the right setting with the right guys, he might stay true to form and finish a song all the way through,” Stout said. “And we got him into a little room with a bunch of real musicians, and he just nailed it.”

The album punched Washington’s ticket to Japan, where he played a festival alongside the likes of Belle and Sebastian, Courtney Love, and Jack White. But his erratic personality eventually wore out Stout. (Stout recalls an impatient Washington urinating in his pants in the lobby of a five-star Japanese hotel.)

“A lot of these guys are their own demise, and if Joe had cleaned up and played straight, he could have been another Buddy Guy,” Stout said.

Regardless of his antics, Washington remained a magnetic local figure whose popularity cut across both social classes and musical cliques. His backing band featured professional musicians like Kevin Blessington, a drummer with a background in musical theater; bassist Chris Henrich, from the rock band Chlorine; and trombonist Dr. William Cohn, a renowned heart surgeon. (Seeing an eminence like Dr. Cohn backing Washington was like the prospect of Dr. Denton Cooley thumping his upright bass behind Lightnin’ Hopkins.)

Washington was in and out of hospitals with a variety of ailments for much of the last decade of his life. But in the end, it was all about the music: he had to be talked out of playing his band’s regular Tuesday night gig at Boondocks the week he died.

Photo by Paul Davis