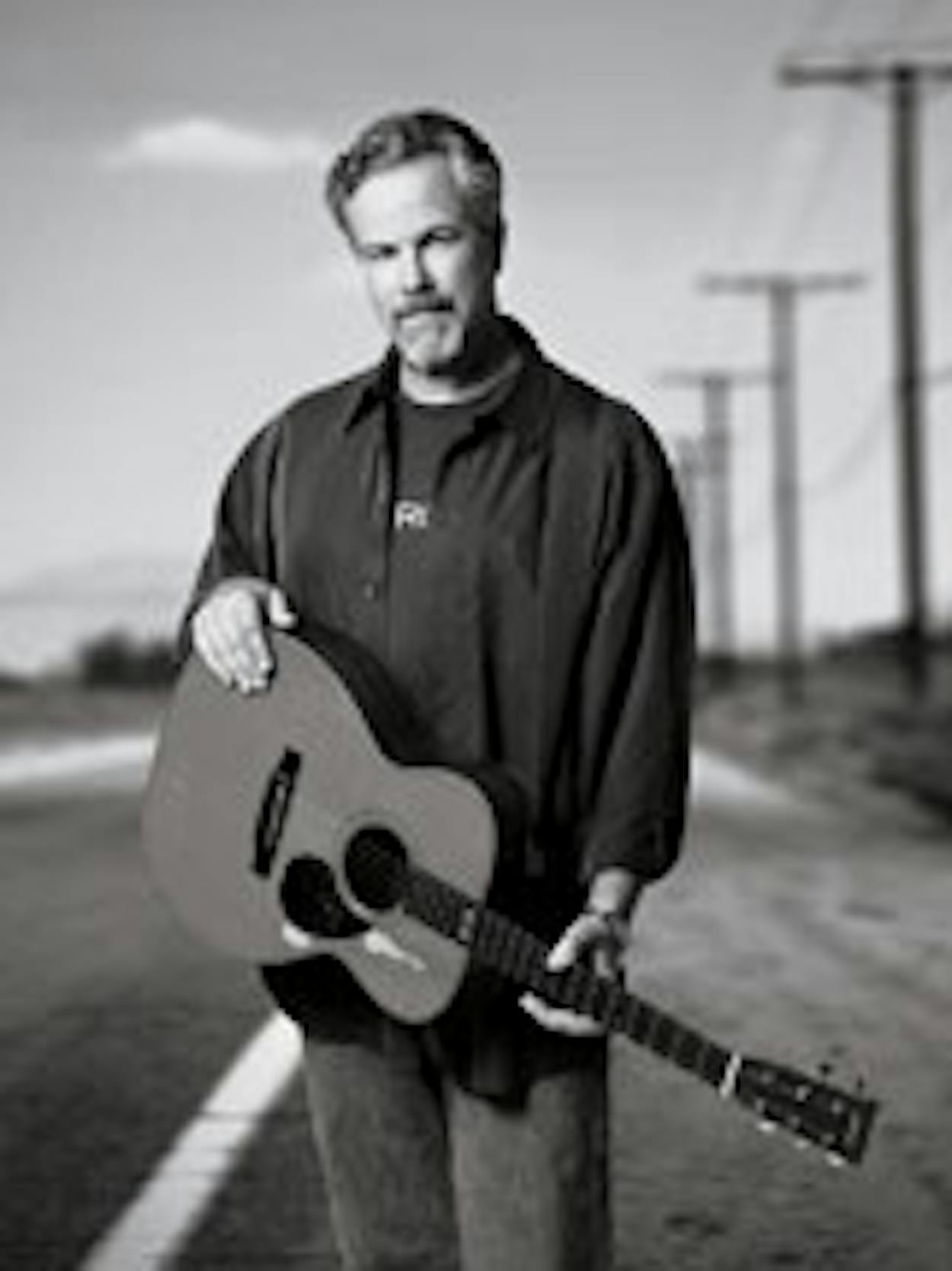

The 55-year-old country singer-songwriter has come a long way since his days as an English major at A&M; he spends about half the year playing to enthusiastic fans and has just released his eleventh studio album, READY FOR CONFETTI (Lost Highway).

You live out in Kerrville, yes?

I’ve always liked the wide-open landscape, although this summer is about to wear on me. I think I’m going to have to turn into a beach person or something. This summer is just so brutal, it’s unbelievable. But during any normal year, I just like it out here.

Tell me about your scriptorium.

It’s this shack that I built—it’s not really a shack, it’s a neat little rock building, three hundred to four hundred square feet—and it’s got my books and my guitars and a little bitty jail bed that unfolds off the wall. I go out there and I find that I’m able to write better when I have a lot of solitude. So I sequester myself in this place and nobody bothers me, and I don’t take a cell phone there or anything.

But you didn’t write this new record out there. You wrote it on the road.

I had a long-standing rule that the road is a really poor place to write songs because, for one thing, you’re tired—I get kind of tired—and for another, it’s just hotel room after hotel room after hotel room. I finally decided that maybe that was just mental and I needed to learn how to get over that. So I decided to trash all those rules and dig in a little deeper and work a little harder at writing on the road. I wrote stuff on the bus and in crappy Days Inn hotel rooms, and some of the songs were quite colorful.

I assume you write the words first?

I always think of the music as being the engine and the words being the driving force. You’ve got the engine rolling, and it’s revving or it’s just idling or something, but it’s going there, you can feel it, and then the words put the whole thing in motion.

I think you have some songs that are misunderstood by some fans and understood by others. Does that frustrate you?

Not too much. I always feel like people take away from songs what they want to take away from them. It’s kind of like telling a joke; if they don’t really get it, explaining it never helps. You go, “Oh, look, this is why this joke is funny, right?” And they go, “Oh, yeah, okay, I get it.” But they don’t laugh. So if what I’m saying doesn’t totally translate, either I’m a little bit at fault or maybe we just don’t think the same.

Talk to me about “Black Baldy Stallion,” the song that starts the album. It’s a cowboy song about a guy riding his horse at night to find a woman. Is it based on a true event?

No, that was one of the ones that I wrote on the back of the bus. I can’t avoid writing cowboy songs; there’s one on almost every record I ever put out—if it’s not mine, it’s somebody else’s. And this time, the story just sort of fell out of my head.

This wouldn’t be a Robert Earl Keen album without some controversy. On “The Road Goes On and On” you sound as if you’re hitting back at someone pretty specific: “You’re malicious and downright cruel, superstitious, so uncool. Best wishes, you loudmouth fool; I hope I never see you again.” You want to talk about it a little bit?

Well, it’s kind of difficult to talk about, you know? I felt like this individual had been picking on me for a long time, and I was sick of it. So instead of getting really ugly about things—I don’t really believe in lawsuits or threats—I took the Alexander Pope road and answered this guy in song. We’ll just have to see what happens.

I assume it’s about Toby Keith.

Yeah.

I read that you typically play more than 180 days a year. Is that still true?

No, I’m out on the road 180 days a year. I play about 120 days, and counting travel days and the days in between shows, it translates to about 180 days.

Are you slowing down at all?

It doesn’t seem to be slowing down, but it’s kicking my ass a lot harder.