San Antonio, June 1964. The pasty-faced guys from England waiting in the wings were getting a big kick out of singer Bobby Vee’s saxophonist, whose only pair of black suit pants had ripped right before showtime. The big guy with the Texas accent was quite the sight onstage in his Bermuda shorts and cowboy boots.

To the members of the Rolling Stones, Slaton native Bobby Keys was a larger-than-life character, the true Texan they’d hoped to meet when they played the Teen Fair at San Antonio’s Freeman Coliseum, their second-ever show in the United States. They couldn’t have been less alike, the gregarious horn player from Lubbock County and the British Invasion group from London. But they had Buddy Holly in common. As a boy, Keys had run errands for Holly and later sat in on sax with Holly’s band. The Stones’ current single was a cover of Holly’s “Not Fade Away,” and they wanted to know everything about their late hero. That night at the Ramada Inn, where Keys and the Stones had adjoining rooms, they talked well into the morning.

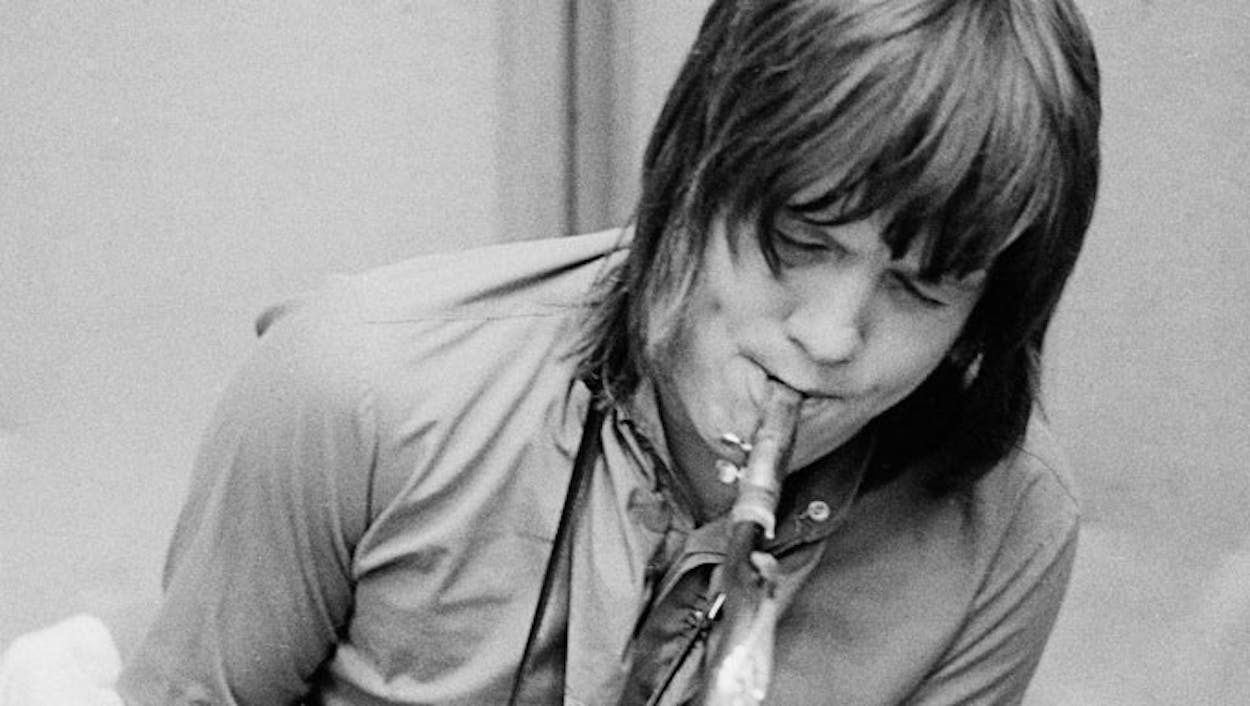

“I didn’t tell him that night, but Keith [Richards] reminded me of Buddy,” said Keys in late September, sitting backstage at Lubbock’s Cactus Theater, where he was playing a gig with Joe Ely. “Keith had a look in his eyes of such determination, like he had no doubt that he was going to be a star. Buddy had that same look.”

The West Texan and the Brits moved in different circles for a while but met again five years later in Los Angeles, when a chance encounter with Mick Jagger in a studio hallway led to Keys’s adding his trademark honking, squealing sax to “Live With Me,” a track from Let It Bleed. He’s been arguably the Stones’ most popular sideman ever since, and as the World’s Greatest Rock and Roll Band celebrates its fiftieth anniversary this winter, he’ll be up there with his sax, joining the band for four big-ticket shows in London and Newark.

“It’s a very well-paying gig, and they give me free clothes,” laughed Keys, 68, who stays sharp fronting a bar band in Nashville, where he’s lived for twenty years. “Plus I know all the songs.”

At this point, the Stones could hire anyone to play sax and still sell out of high-price tickets in minutes, as they already have for the anniversary shows. But Keys is the saxophonist who makes the Rolling Stones sound like the Rolling Stones. Since that first U.S. tour, the band has played everything from hard rock to disco and pioneered the collision of sex and drugs and private jets that defines the rock star lifestyle. Through all of that, only a few things have kept them connected to the American roots music that first inspired them. One of those things is Keys, whose sound is grounded in the work of Texas tenor players like Illinois Jacquet, Arnett Cobb, King Curtis, and David “Fathead” Newman. It’s no accident that his greatest contributions to the Stones’ sound came on Let It Bleed, Sticky Fingers, and Exile on Main St., albums that marked the band’s late-sixties/early-seventies creative peak.

Keys’s most famous solo, on the deathless radio staple “Brown Sugar,” came about after he jammed with the band on the tune during a birthday bash for himself and Richards at London’s Olympic Studios on December 18, 1970. The song had already been recorded with a Mick Taylor guitar solo, but after Keys thrilled the partygoers with his skronks and trills, he was asked to overdub the 28-second improvisation that continues to pay his bills thanks to the residual checks.

READ MORE: Dissecting Bobby Keys’ Saxophone Solo on “Brown Sugar”

With a personality as extroverted as his sax playing, Keys has contributed almost as much to the Stones’ mythology as he has to their discography. He and Richards were born hours apart in 1943 and have been best friends since the haphazard sessions for Exile on Main St. In Richards’s 2010 memoir, Life, he describes Keys as “a soul of rock and roll, a solid man, also a depraved maniac.”

“I think at first I was a bit of a novelty in London,” said Keys, who shared a flat with Jagger when both were doing the party scene. “It was like, ‘Meet my crazy friend from Texas. Put drugs and alcohol inside him and watch what he does.’ ” He was never the most famous man in the room, but in swinging London, being in the top five was just fine.

Some celebrated Keys stories: He once filled a bathtub with Dom Pérignon to impress a French woman he’d met at a hotel bar. He started a fire at the Playboy Mansion in Chicago. Then there’s the infamous 1972 tour footage of him and Richards heaving a TV set out of a hotel window. “To this day, that’s how a lot of folks know me,” he complains. “I could say, ‘But I played on all these great records,’ and most people would go, ‘Yeah, but you’re the guy who threw the TV set out the window.’ ”

Keys had become an important part of the Stones’ sound, but getting caught up in the lifestyle led to his split from the band, in 1973. Addicted to heroin, he left abruptly for rehab, with Richards footing the bill. His attempts to rejoin after he kicked junk were rebuffed by Jagger, but by that point Keys—usually accompanied by Fort Worth–born trumpet player Jim Price—had become the go-to sax player for rock royalty on both sides of the Atlantic. He played with Eric Clapton, Harry Nilsson, Donovan, Keith Moon, the Faces, Humble Pie, Joe Cocker’s Mad Dogs and Englishmen, and three of the four ex-Beatles.

Keys’s fondest memories of his non-Stones studio work involve John Lennon, who hired him for 1974’s Walls and Bridges. When Keys showed up at the studio and Lennon told him the horn charts were almost ready, Keys was mortified. He can’t read music. “I feared a death of embarrassment, because the other horn players were top session guys,” Keys recalled. “John took me to the stairwell and, with an acoustic guitar, played me all my parts. He kept going until I had it down, one of the many reasons I loved that man.”

Eventually, Richards got Keys back in the Stones’ touring band, though he was originally relegated to two songs: “Honky Tonk Women” and “Brown Sugar.” During the 1981 tour, he met fellow Panhandle native Joe Ely, whose band opened a Stones show in Tempe, Arizona. During the next eight years, while the Stones took a break from touring, Keys played with Ely’s band. “With the Stones, I never touched my bags,” Keys said. “Someone packed for me and put them on the private jet. So it was a bit of a difference to travel in a van with seven guys. But playing with Joe rekindled the spark of why I wanted to play music in the first place.”

With Ely’s band, Keys carried his belongings in a bowling-ball bag. “He always kept the title to his car in the bag, and I asked him why,” said Ely. “He said it was to remind him of the time he parked at the airport to go do a Stones session that was supposed to last a week and he ended up gone for two years.” His car was eventually impounded, and he needed the title to get it back.

A few months ago, a reunion with Ely brought Keys back to Lubbock, where he talked about being transformed by hearing rock and roll for the first time. Every rock musician has a story like that; Jagger and Richards heard their calling in the songs of Chuck Berry and Slim Harpo. But Keys’s inspiration didn’t come from hearing records. When he was ten years old, he was awakened one morning by the sound of a loud guitar coming through his bedroom window. He ran out of the house and climbed a tree in his front yard to see a band playing on a flatbed truck a block away. They were there celebrating the grand opening of a gas station, and the man playing the electric guitar was Buddy Holly.

“That did it for me,” said Keys. “Rock and roll was calling, and I said, ‘Here I am.’ ”

READ MORE: Dissecting Bobby Keys’ Saxophone Solo on “Brown Sugar”