Your opinion of the Texas Rangers likely reflects something about how you or your ancestors first entered into the epic tale of the Lone Star State. If you’re the descendant of Anglo settlers who squared off against fierce indigenous resistance and recalcitrant, long-settled Tejanos, then you probably regard the Rangers as the venerable knights-errant of the sprawling Central Plains and southern brush country, the guardians of civil order on the lawless frontier, ever dutiful in their white cowboy hats, ringed silver-star badges, and Colt .45 sidearms. If your forebears were Tejanos whose colonial patrimonies were stolen, often violently, then you may believe the early Rangers to have been nothing more than bloodthirsty thugs for hire, lawless instruments of white supremacy.

Or maybe you know someone who thinks they’re just a professional baseball team. Many newcomers to Texas remain aloof to these legacies.

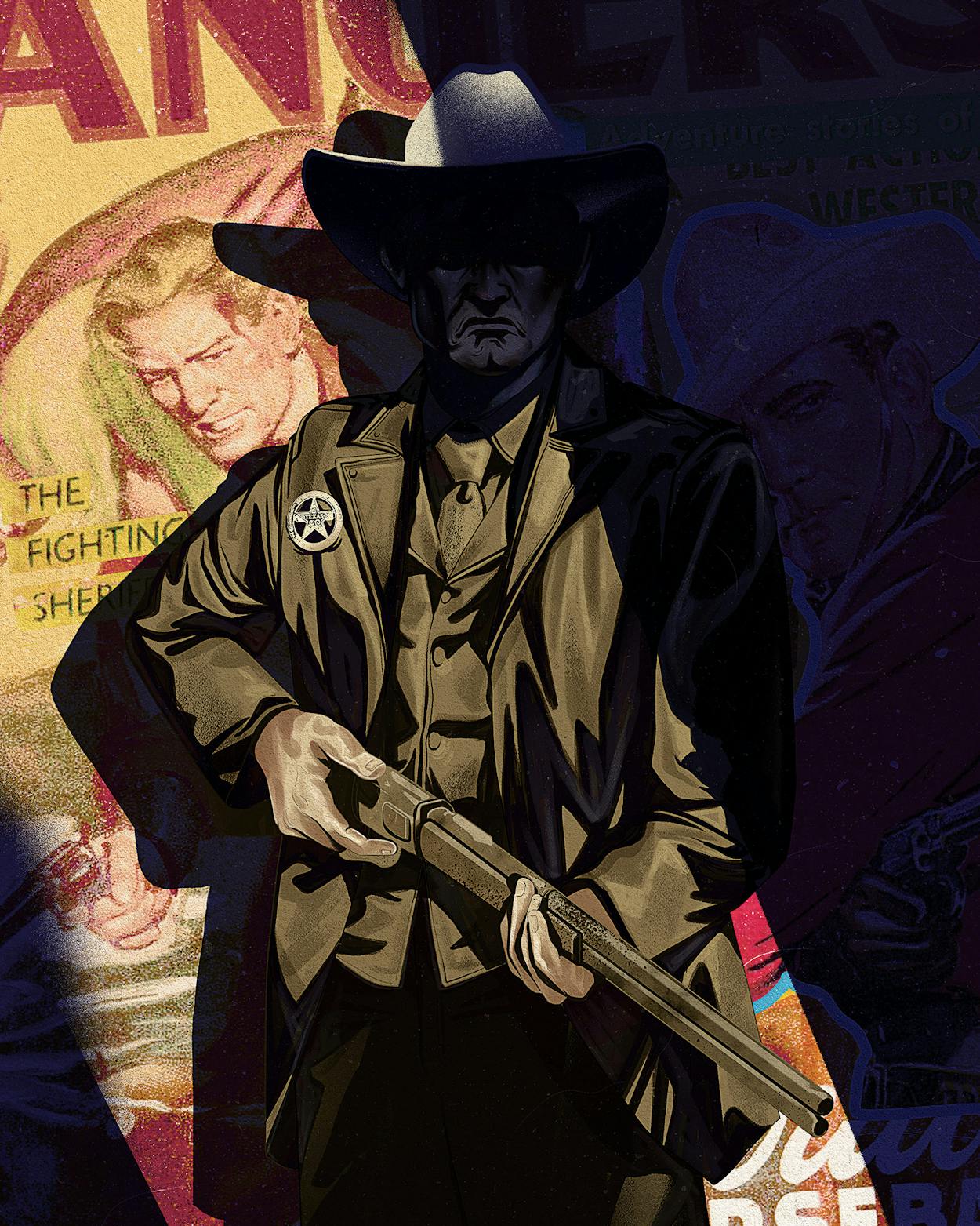

For most of the state’s history, the laudatory picture of the Rangers has prevailed, among both historians and the general public. When I was a child, school trips to San Antonio’s Witte Museum always included a visit to the shrine-like exhibition of Ranger memorabilia housed in a limestone Greco-Roman-style building that resembled a mausoleum. The display included saddles, pistols, rifles, and badges, along with a few photographs of famous Rangers. The quiet, mahogany-paneled room, with its august and somber presentation of these implements, was meant to evoke reverence and awe, with little reference to the history it represented.

In his 1935 opus The Texas Rangers: A Century of Frontier Defense, the historian Walter Prescott Webb anatomized the typical Texas Ranger as “essentially a fighting man.” In his foreword to the 1965 edition of the book, President Lyndon B. Johnson extolled the group’s heroic ethic, observing that “thought of self would never deter the Ranger from fulfilling the commitment of his vows as an agent of law, order, and justice.”

But over the past two decades, the history of the Rangers has been contested. Scholars such as Benjamin Heber Johnson, William D. Carrigan, Clive Webb (no relation to Walter Prescott), and Monica Muñoz Martinez have taken Webb’s landmark book to task, publishing works that shine a harsh light on the Rangers’ involvement in lynchings and other extrajudicial murders of Mexicano Texans. Carrigan and Clive Webb cite historians who “estimate the number of such victims to be as low as 500 and as high as 5,000” between 1910 and 1920, a time that came to be known among the Mexican Americans of South Texas as La Hora de Sangre (“The Time of Blood”). Even Webb wrote in his book of “the death of hundreds of Mexicans, many of them innocent, at the hands of the local posses, peace officers, and Texas Rangers,” though this acknowledgment doesn’t seem to have much altered his opinion of the organization.

None of these recent historians’ works can be found in the bookstore of the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, where one will, instead, find titles such as The Ranger Ideal: Texas Rangers in the Hall of Fame (two volumes) and Yours to Command: The Life and Legend of Texas Ranger Captain Bill McDonald.

Now, just three years shy of the Rangers’ bicentennial, comes another history that likely won’t make it into the Hall of Fame’s bookstore: Doug J. Swanson’s Cult of Glory: The Bold and Brutal History of the Texas Rangers (Viking, June 9), which rigorously chronicles two centuries of Ranger misadventures and atrocities, as well as commendable operations undertaken by the Rangers in recent decades. At more than four hundred pages, Cult of Glory strives to be as panoramic as possible, telling a big story on a big canvas and featuring characters with names like “Old Paint,” “Three-Legged Willie,” and “Lone Wolf.” But it also strives to supplant the Ranger narratives of yore by synthesizing decades of others’ research as well as Swanson’s own findings.

Swanson, a Florida transplant to Dallas who graduated from the University of Texas at Austin in 1977, subscribed for many years to the heroic image of the Rangers that’s the default position of most Anglo Texans. In a recent interview he said that, like many young people of that time, he was first exposed to the Texas Ranger legend through television, specifically the handsome and upright exemplars of the Ranger tradition celebrated in shows from the fifties and sixties such as Texas John Slaughter, part of the Wonderful World of Disney anthology series, and Laredo, an NBC drama that featured three Texas Rangers stationed in South Texas. Such shows are part of a long lineage of Broadway plays, dime-store novels, radio dramas, and films that have long portrayed the Rangers as honorable, stoic, and fair, as well as impeccably groomed, whether it was Tom Mix or Robert Culp or Chuck Norris filling out that starched white shirt.

As an investigative reporter for many years at the Dallas Morning News, Swanson had numerous occasions to cover Texas Ranger cases, including the organization’s role in investigating a 2005 sexual abuse scandal involving the Texas Youth Commission. The Rangers, in collaboration with the FBI, revealed that a number of TYC officials had had sexual relations with juveniles in their care. “I thought they led a very effective investigation,” Swanson recalled. “So I didn’t come into this book in any way wanting to do a hatchet job.” (Full disclosure: Swanson and I share the same publisher and the same editor.)

Even so, Swanson’s attempts to get interviews with agency leadership were unsuccessful, making his book something of an unauthorized biography that relied on extensive use of publicly available records in libraries and historical archives. “I’ve got a file full of letters declining or pushing me off,” he says. “So at a certain point, I just started writing.”

As Swanson tells it, the history of the Texas Rangers begins before the history of Texas itself. In 1823 Stephen F. Austin hired ten men to act as “rangers” in order to carry out a punitive expedition against the Karankawa tribe in South Texas, whom he believed couldn’t coexist with Anglo settlers. “There is no way of subduing them but extermination,” he wrote. It was a task that the nascent Rangers eventually accomplished.

The Texas Rangers were officially established in 1835, a year before the Republic of Texas came into existence, and as Swanson makes clear, their history is inseparable from the romanticized tales of the creation and manifest destiny of Texas. It’s as if the state needed its own Praetorian Guard to fulfill its imperial ambitions.

By 1846, the Rangers were deployed as the shock troops of the United States’ invasion of Mexico, extending over the republic’s newly established southern border the violent settling of scores and land expropriation that they had already practiced against the Mexicanos of South Texas. “Among the regular troops,” Swanson writes, “the Rangers owned a deeply rooted reputation as arrant killers.” Among the Mexicans, the Rangers came to be known as Los Diablos Tejanos. “The Mexicans raised it as a cry of alarm,” Swanson writes, “or they spat it as a curse. The Rangers wore it as a crown.” It was a sobriquet that would outlive the Rangers’ enterprises in the Mexican-

American War.

As an example of the Rangers’ brutality, Swanson cites an 1855 incident, one of the most gruesome episodes in the organization’s history, in which a company of Rangers, led by Captain James H. Callahan, looted and set fire to the Mexican border town of Piedras Negras, just across the Rio Grande from Eagle Pass. “They were said to be hunting Indian raiders,” Swanson explains, “but they were probably looking for escaped slaves, for bounty.” Despite the violence the Rangers inflicted on a town of innocents—the sort of act that would have destroyed the reputation of a less venerated organization—the episode seems to have made little impression on Walter Prescott Webb. “He gave that story one page,” Swanson says.

The residents of Piedras Negras were later paid reparations by the U.S. government. But Texas politicians were hardly contrite; after Callahan’s death, a county just east of Abilene was named in his honor. And today, his body lies in the Texas State Cemetery, in Austin, one of thirty Rangers who have been interred there over the centuries.

Murderous violence against Indians, Mexicans, and Mexican Americans was only one part of the Rangers’ deep CV. As Swanson unfolds the succeeding history, the Rangers engaged in bounty hunting for escaped slaves in Texas and Mexico, largely turned a blind eye to the lynching of black people, and, later, were deployed to break a United Farm Workers strike. By 1967, Swanson summarizes, “the Rangers had evolved, over the course of a hundred years, from fighting fierce Comanches to pinching humble fruit pickers.”

But Ranger pride is undiminished. Swanson points to the statue of an iconic Texas Ranger at Dallas Love Field Airport that bears the trademark slogan “One Riot, One Ranger.” “The model for that statue?” he says. “Ranger Jay Banks, who [on the orders of Governor Allan Shivers] blocked school integration in Mansfield, Texas, in 1956.” Webb sanitized this era of Ranger misdeeds as well. As Swanson’s research reveals, Webb’s archives include numerous memos regarding the Rangers’ 1919 efforts to quash the civil liberties of black Texans and chase the NAACP from the state. Not a word of it appeared in Webb’s book—which, even today, the Handbook of Texas calls “the definitive study of this frontier law enforcement agency.”

Though the Rangers did investigate racial tensions in Texas following a riot in Longview in 1919, Swanson reports, they did not, as has been widely reported, engage in an official campaign against the Ku Klux Klan; they devoted more of their efforts to probing civil rights groups, which they regarded as creating the racial tensions in the first place. “It was an open secret that an untold number of Rangers held Klan sympathies, if not memberships,” Swanson writes.

The mythologizing of the Rangers that has long taken place in the realm of popular culture has continued as well. Last year’s feature film The Highwaymen starred Kevin Costner as the legendary Texas Ranger Frank Hamer, who tracks down and eventually ambushes and kills Bonnie and Clyde. The film (directed by a Texan, John Lee Hancock) portrays Hamer as an honorable, if haunted, man seemingly burdened by the past. At one point, his partner, Maney Gault (Woody Harrelson), shares with a group of policemen a difficult memory of him and Hamer massacring Mexicans in the borderlands, while a stoic Hamer sits silently nearby. We’re supposed to recognize that an older, wiser Hamer bears the emotional scars of his dark past.

For sure, this is an improvement over the saintly Ranger portraits we’ve seen on-screen before. But it feels like a new way of valorizing the Rangers, in line with the tortured-but-likable antiheroes of premium cable. This would be a harder trick to pull off if the movie had the nerve to show us a notorious postcard depicting Hamer posing with the bodies of four lynched Mexicans. Instead, the swagger of the traditional Ranger has been replaced by a weary existential resolution to carry on the fight, which contemporary sensibilities will find more believable than the same old hagiography.

One reason contemporary writers are able to unearth so much of the Rangers’ bloody past is because Mexicano memories are long and the stories have been passed down from generation to generation.

On the other hand, there are voices in the contemporary Texas cultural scene that follow the lead of the revisionist historians. In his 2018 historical thriller El Rinche: The Ghost Ranger of the Rio Grande, the South Texas novelist Christopher Carmona imagines a revenge narrative in which the Rangers get their comeuppance. At the beginning of the book, which is set in the late 1890s, a young Mexican American is left for dead after an assault by Texas Rangers that kills his father and brother. He is rescued and takes up with Japanese settlers in a small village near Port Isabel, where he becomes an adept ninja. He uses his new martial arts skills to avenge his family without deploying lethal violence, eventually bringing the guilty Rangers to justice. Carmona writes that the book was inspired by stories told to him by his grandfather, “who experienced, first-hand, the terror of the Texas Rangers.”

One reason contemporary writers like Swanson are able to unearth so much of the Rangers’ bloody past is because Mexicano memories are long and the stories that never made it into Webb’s book have been passed down from generation to generation. Recently, a coalition of scholars honored those stories by successfully petitioning the Texas Historical Commission to place three commemorative plaques along the border where Ranger atrocities occurred.

The professionalized Rangers of today are a far cry from their predecessors. Last year, Ranger James Holland elicited a confession from serial killer Samuel Little to the murders of as many as 93 women. After the 2017 Super Bowl, the Rangers were tasked with finding out who stole Tom Brady’s jersey from the New England Patriots locker room in Houston. They were unsuccessful in that case—the jersey turned up in Mexico. As Swanson puts it, “They’re still answering the call, still ready to ride to the rescue. Ready to chase robbers, lasso rustlers, punish killers, and nab locker-room pickpockets. And to do it with the swagger—if not the abandon—of old.”

One question Swanson leaves unasked and unanswered is what sort of future the Rangers have—or if they should even have one. It’s not, after all, clear what the Rangers’ obligations are in the twenty-first century, when the much-larger Texas Highway Patrol is Texas’s de facto statewide police force. Is there a good reason, other than a nostalgia that is not universally shared, for both organizations to exist? Swanson observes that in recent years, the Rangers have had their portfolio boosted, taking on cold cases and public integrity cases. They’re also officially back in the business of border policing, with a Border Security Operations Center headquartered in Austin. “But we really don’t know what they’re doing with that,” Swanson says.

The question of whether we still need the Rangers has been in the air for a good while. The organization briefly went dormant in 1848, after the conclusion of the Mexican-American War. In 1918 state representative J. T. Canales, of Brownsville, organized the Legislature’s first official inquiry into the Rangers’ violent operations in the borderlands, curtailing the impunity they had long enjoyed. Governor Miriam “Ma” Ferguson sacked the entire force in 1933 in an act of political revenge, replacing them with what Swanson describes as “cronies and hacks.” In 1935 the force was reconstituted under DPS, becoming that agency’s detective branch.

The same group of scholars who successfully pushed for the placement of commemorative markers at the sites of Rangers atrocities plans to seek an official apology from the state during the Rangers’ 2023 bicentennial. Perhaps, in the spirit of truth and reconciliation, that would also be a fitting occasion for the first public hearings in a century to examine the Rangers’ past, present, and future.

Cult of Glory includes an account of state representative Charles Lieck, of San Antonio, the descendant of a family that immigrated to Texas from Spain in 1790, who introduced legislation in 1957 to eliminate the Rangers. “We don’t need a state gestapo anymore,” he said, an incendiary phrasing that likely doomed whatever slim chance his bill may have had of passing.

At the time, Swanson’s future employer, the Dallas Morning News, offered a response to Lieck that probably represented the opinion of many Texans: “He might almost as well propose that the Alamo be razed and the ground used for a parking lot.” Indeed, not only did the bill fail—lawmakers quickly drafted and passed legislation making it illegal to ever abolish the Texas Rangers.

This article originally appeared in the June 2020 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Bold and the Brutal.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Books

- Dallas