This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Once it was all like this: untrodden by man, cushioned in silence, wild. Something of that original Texas survives in the four natural areas included here—a South Texas woodland, a shallow bayou in deep East Texas, salt flats not far from the New Mexico border, an isolated reach of the Rio Grande. If they have anything in common it is their seclusion. Each is for the most part private land; permission is required to visit, and permission is seldom granted. Though none remains unsullied wilderness in the judgment of those who are doctrinaire about such matters, none has been blighted beyond recovery. They are wild places still.

Brush

The Falcon Thorn Woodland

Disgorged from the turbines of Falcon Dam, the Rio Grande begins its final, sluggish journey to the sea. The great impoundment completed in 1953 is the last barrier to the once-wild waters that have churned their way down from the Big Bend canyons’ rapids and cliffs. Beyond the breaks of Starr County the brown river eases, tamed and spiritless, toward the estranging coastal sands.

For a short distance below the dam an isolated remnant of subtropical thorn woodland luxuriates along the riverbank. This brief thicket is one of the few surviving pockets of native vegetation in South Texas. The woodland, its adjacent alluvial terraces, and the chaparral uplands harbor South Texas’ most distinctive collection of plant and animal life. Species found in northern regions and the western deserts coexist with others native to Mexico and Central America, many of which reach their northernmost distribution here.

The Mexican burrowing toad and the Mexican white-lipped frog appear in the United States only in Starr and neighboring Hidalgo counties. The poisonous giant toad, which secretes venom through its skin, ranges from the South American tropics to this section of southern Texas. The bird population is so extraordinary that birders from all across the United States make periodic pilgrimages to observe the Falcon avifauna. Twenty-one species of tropical birds come to Falcon and go no farther, attracted, in part, by its tall timber, dense undergrowth, and the few miles of clear water below the dam. Among the notable birds are the brown jay (a native of lowland Mexico and Central America that began nesting at Falcon in the mid-seventies), the green jay, the chachalaca, the gray hawk, the hook-billed kite, the black-headed oriole, Lichtenstein’s oriole, the olive sparrow, the groove-billed ani, the ferruginous pygmy owl, and the ringed kingfisher.

The botanical treasure of the seven-mile stretch between the dam and the sleepy little town of Salineno is a stand of thirteen Montezuma bald cypresses, the largest of which has a circumference of more than fourteen feet. The drooping, coniferous branches of this noble tree are a not uncommon sight southward into Mexico, but this is the only known grove in the United States. Three other rare plants have been identified in the vicinity of Falcon: Gregg wild buckwheat, previously seen only at one site in Hidalgo County; slashleaf heartseed; and the vivid, orange-petaled Amoreuxia wrightii. Texas ebony and anacahuite, less rare, also reach their northern limits here; and natural gardens of peyote, the hallucinogenic holy cactus of the Indians, thrive in Starr County’s sandy soil as nowhere else north of the Rio Grande.

Deceptively somnolent by day, Falcon Woodland is transformed after dark. Its night sounds throb with life: the jetlike whine of crickets and katydids, the irregular chorusing of frogs, the insistent buzz of circling mosquitoes, and, of course, the eerie calls of night birds. In summer the lesser nighthawk darts, batlike, scattering hollow feline purrs, and the pauraque adds a multisyllabic whistle. Carry a powerful artificial light into the woods at night and meet the enveloping tropics’ enigmatic stare: the pauraque’s eyes, caught in the beam, shine hot pink, and along the ground ephemeral phosphorescent mushrooms glow.

Probably no other place in Texas combines such hospitality to plants and animals with such extreme inhospitality to man. William McClintock, passing through the region in the nineteenth century, expressed the definitive truth: “There is nothing of the vegetable world on the Rio Grande, but what is armed with weapons of defense and offense.” Even allowing for a certain mellowness along the floodplain itself, this is cruel country—as Cabeza de Vaca found, as Santa Anna found, as anyone finds today traversing it on foot. It is not to be trifled with.

Especially not in summer, when the effective temperature (a combination of humidity, heat, and air movement) is the highest in the United States—worse than Death Valley’s, comparable to the Red Sea’s. The wife of an Army officer stationed at Ringgold Barracks (at Rio Grande City) in the 1850’s spoke for generations when she declared, “There never was a country more unfitted by nature to be the home of civilized man than this region of the lower Rio Grande of Texas. It seems to hate civilization.”

The region has always been a hard and uncomfortable place. The aboriginal Coahuiltecans were nomadic wanderers who wore few clothes, fashioned primitive tools from pink and gold rhyolite, and ate anything their systems could digest—including, if the archeological evidence is to be believed, substantial quantities of snails. The Coahuiltecans subsisted in small groups of warring bands, their cultures differing from drainage to drainage across South Texas. As if living out a curse as old as Genesis, they spoke mutually incomprehensible languages.

By 1840 the Coahuiltecans, stricken by disease and assimilated into the Mexican population, had entirely vanished. The first Spanish explorer, Alonso de León, crossed the river in 1686 at the Salineño ford, which he called El Cantaro. Official Spanish interest focused elsewhere for several decades, but in the half-century after 1739, successful colonial outposts were established along the south side of the river, among them Camargo, Reynosa, and Mier. Companion settlements on the north side failed, but by 1781 every parcel of riverfront land had been claimed

Development of the Falcon region, like much of the rest of the Nueces Strip, was delayed by violence and disorder. Indian raids (the last, by Comanches, Kiowas, and Apaches, in 1837) were followed by a lawless period of banditry. Mexican invasions of the Republic of Texas were countered by freebooters like Colonel W. S. Fisher, whose Texian force, captured under a flag of truce in 1842 at Mier, was decimated and imprisoned. The establishment of Ringgold Barracks in 1848 was a signal that order would prevail. With occasional lapses, it eventually did. Soon the Roma-Matamoros river run was an important commercial passageway for hides, lead, and wool. In the following century, agriculture and ranching established themselves—less securely in Starr County than elsewhere in the Valley, but sufficiently well to alter the land on the perimeter of the Falcon Woodland.

Grasslands have given way to chaparral: nothing remains of the sight that greeted visitors in the 1850’s, when grass extended from the river at Rio Grande City to a point sixteen miles inland. With it has gone the water table that sustained the intermittent streams used by the Coahuiltecans. Consequent erosion in the flood-prone arroyos has carried away much, though not yet all, of their pitiful remains.

In recent years the chaparral has in turn given way to the effects of quarrying, grazing, and cultivation. Deprived of protective vegetation and assaulted by pesticides, the animal life of the region has undergone profound change. Since mid-century the number and variety of mammals have fallen sharply; the jaguar has disappeared altogether, with the ocelot and the jaguarundi hard on its heels. Such diverse birds as the olivaceous cormorant, the black hawk, the red-billed pigeon, the tropical parula, the hooded oriole, and the elf owl have been adversely affected by the clearing of the land and by the increased human presence near Falcon Dam.

Man is closing in on the Falcon Woodland. But in the heavy, humid heat of a summer afternoon, as blue spiny lizards scramble over the grainy rocks and pale green branches of Montezuma cypress arc lazily in a gust of wind, he seems as distant as the polar ice.

Swamp

Harrison Bayou

Harrison Bayou, a watercourse so slight as scarcely to deserve a name, flows uneventfully for a half-dozen miles through East Texas bottomland forest before spending itself in the shallows of Caddo Lake.

Consider that forest. Once it stretched almost unbroken to the Atlantic. Consider its aboriginal inhabitants, the Kadohadacho, kin by culture to the tribes of the eastward-facing woodlands, alien to those of the plains and the open sky. And consider the settlers who in turn supplanted them, conferring names on the humblest streams and ordering the land with methodical precision: from beneath that same canopy they came.

At the beginnings of Texas, this was Texas. Eastward lay all manner of familiar things; the rest was an uncertain place. Once Texas belonged to the south, sealed there by terrain of mind as well as land. But now the forest confirms how utterly the idea of Texas has changed since Texians themselves first came to be.

Caddo Lake is the largest natural body of fresh water in the state. Legends rooted in the Indian past attribute its formation to an abrupt upheaval of the gods, who flooded the sunken earth with a gesture angry or beneficent according to the telling. The truth is more prosaic: over time, the collapse of tree-lined stream banks formed a jam of logs so impenetrable that the waters gradually collected behind the accretion of debris.

The result is less a lake in the conventional sense than a problematic maze where the line dividing land from water is often indistinct. From an irregular expanse of open lake, channels and passageways sluice across the enveloping marsh. “A sequence of concealments and digressions,” it has been called, bewildering to eyes unaided by maps. Vegetation and water seem to merge: bald cypress, hyacinth, algae—the vegetation half liquid, the water stirring with hidden greenness. Clear and fluent, Harrison Bayou is a capillary on this aqueous heart.

Well into the 1830’s, the lake and its environs were the domain of Caddo Indians, a loose confederacy of tribes whose bizarre physical appearance seemed preposterously at odds with their intricate hierarchic society. Short of stature and massively tattooed, they purposely deformed their skulls from childhood in furtherance of a now inscrutable aesthetic. Yet theirs was once a civilization higher than any other in Texas: settled, agricultural, provident; capable of storing its harvests for two years, erecting spacious homes by communal effort, maintaining temples where symbolic flames were kept perpetually alight. In the end they peaceably yielded their ancestral lands by treaty and embarked on a restless hegira whose misery lasted for most of a century.

That treaty, displayed at the old courthouse in Marshall, foretells their fate in its Latinate cadences. “Goods and horses” to be paid now, it says, then “ten thousand dollars per annum for the four years next” if the Caddo will remove themselves from the United States “and never more return to live, settle, or establish themselves as a nation, tribe, or community of people within the same.” Like a document negotiated in some baroque drawing room by the plenipotentiaries of European nation-states, it duly bears the witness of its signatories: Jehiel Brooks for the United States and the X marks of 25 illiterate Indian chiefs.

Thus ignobly secured, the Caddo lands became a gateway for migrants from the Southern states to Texas. Stern-wheelers and side-wheelers plied the lake itself, following a channel carved by the Big Cypress Bayou that led upstream to the bustling antebellum port of Jefferson. Cargoes waterborne from New Orleans were tagged with playing cards to indicate their destinations, one clue the unlettered stevedores could always fathom: the king of spades for Jefferson, the king of diamonds for Marshall, and on through the deck to lesser towns along the thriving inland waterway. Floruit Dixie, for a time; and when the war came, the path of commerce became a lifeline to the beleaguered Confederacy, bearing foodstuffs, cotton, and munitions.

Then as now, Harrison Bayou has remained untouched, curling with quiet inconspicuousness through the forest understory. At fifty feet, it is invisible. Winter sunlight turns the surrounding carpet of damp leaves orange; acorns crunch underfoot. Stalled by brush jams or enterprising beaver colonies, the swift-flowing water forms miniature lakes, imitating Caddo.

Around the bayou lie three hundred acres of virgin bottomland hardwoods, the finest stand in Texas. Their isolation saved them from the logger’s ax; their nearness to Caddo saved them from inundation by any man-made reservoir. Now they are fenced within the Longhorn Army Ammunition Plant, immune to harvest. In this protected circle are the state’s largest water hickory and flowering dogwood, along with huge persimmons, overcup oaks, water locusts, water elms, and hawthorns. Flanged bald cypresses tower above the bayou—the sort of trees that foresters gaze upon, computing board feet. Around the lesser hardwoods wind sinewy vines, adhesive, serpentine.

On the sandy ridges the transition to pine forest is immediate: as moisture and soil conditions change by inches, so too does vegetation. Gray squirrels romp through the treetops as if in a festival; bobcat, mink, and feral pig abound beneath the hardwoods. Twenty-nine species of snakes have been recorded nearby, including one, the mud snake, that eats nothing except an eellike amphibian called the siren.

Harrison Bayou is a haven for bottomland birds. The elusive ivory-billed woodpecker may conceivably be here, though no clear proof of its existence has been found. But even in January its woodpecker kin are present, drumming across the leafless distances, interrupted by the more insistent resonance of locomotives on the nearby main line of the Texas and Pacific. Those whistles cut through a woodland idyll like a knife, reminders of old Jefferson, a town brought low by the railroad.

When the ancient logjam that sustained the lake was cleared away by Army engineers in 1873, no community associated with the Caddo region saw its fortunes plummet more quickly than Jefferson. A replacement dam built to restore the level of the lake failed to regenerate its commerce, and Jefferson, stiff-necked and proud, spurned the vulgar railroads whose smoky, raucous presence might have saved it. “This is the end of Jefferson,” warned the president of the Texas and Pacific, and the railroads proliferated in more compliant places, co-opting Jefferson’s fruitful hinterlands.

From a population of 38,000 in its prime, the town within a decade went to decay. In the numbed judgment of its local newspaper, the Jimplecute, “Our people continued to lie still and watch, having been made too confident by a long prosperity.” By 1888 the railroad’s fierce example had been made, in terrorem: Jefferson was a skeleton of itself, a town hanged in irons on a gibbet.

Today, despite much fashionable restoration, the remnant of the city seems to be—not brooding exactly, but meditating on those days of its vanished glories. The platted streets betray the framework of a far larger town, stranding homes among too many telltale vacant lots. Contemporary Jefferson has the slightly abashed air of one who bravely stood up for a principle, only to discover that it was the wrong principle.

In this it is like the South itself, whose legacy is kept with the rest of Jefferson’s past in the town museum. There the curators preside over collections of Confederate memorabilia. Relics that not so many years ago shimmered with the respect owed to noble causes now seem invested with unadmitted shame; preserved long after the popular faith that such things matter has dissolved, their light dusting of embarrassment deepens with each passing year.

Like the Texas that once was steeped in Southern ways, the museum in Jefferson seems less a memorial to the Confederacy than its mausoleum, a kind of graveyard where disquieting memories lie visibly interred, too recent to remove, too burdened with ambiguities of conscience to revere. Those Texians are strangers to us now.

Row after row with strict impunity

The headstones yield their names to the element

The wind whirrs without recollection. . . .*

Eastward the meandering Big Cypress rolls untenanted to Caddo Lake. Where once low fields of cotton prospered on land laboriously cleared, now spindly pine plantations rise in geometric lines; at man’s behest the shadowed forest reclaims its own.

Turn your eyes to the immoderate past,

Turn to the inscrutable infantry rising

Demons out of the earth—they will not last.

Now that the salt of their blood

Stiffens the saltier oblivion of the sea . . .

What shall we say of the bones, unclean,

Whose verdurous anonymity will grow?

The ragged arms, the ragged heads and eyes

Lost in these acres of the insane green?*

* Excerpts from “Ode to the Confederate Dead,” by Allen Tate, reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Desert

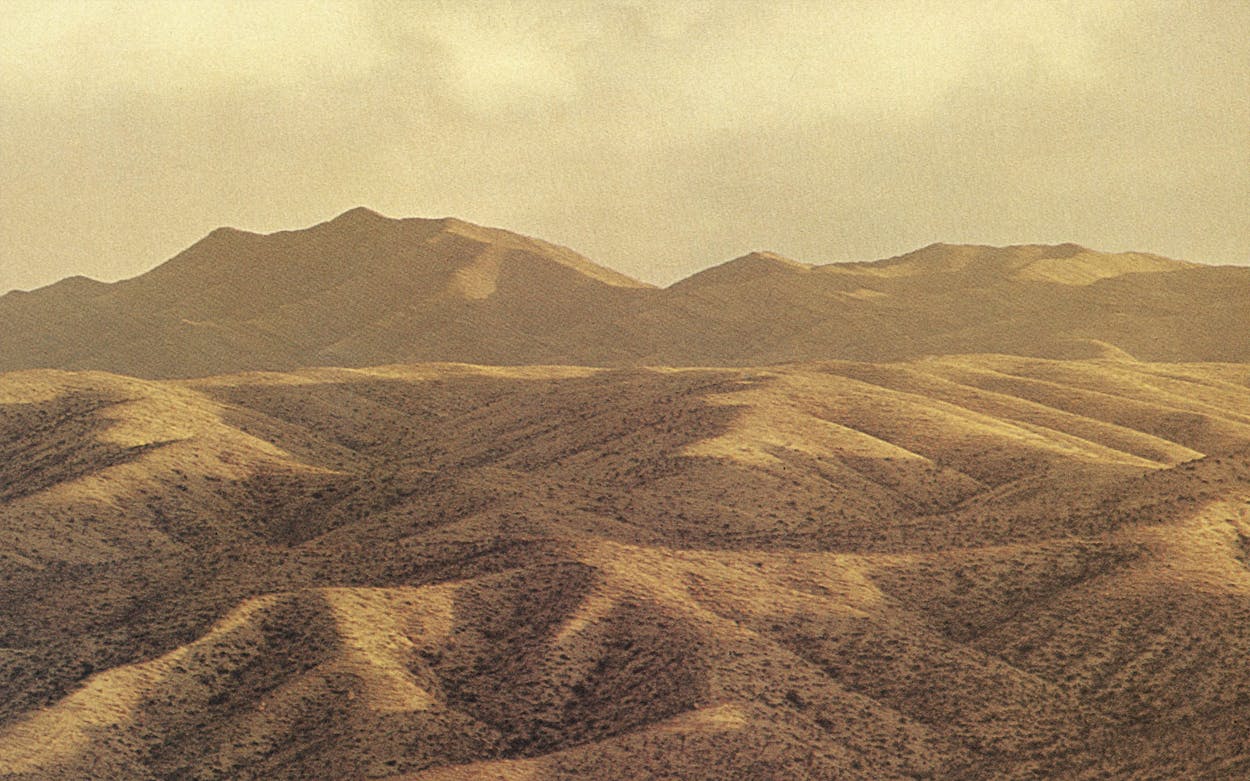

The Salt Flats

The descent from the gusty elevations of Guadalupe Pass westward onto the level desert floor is one of the sharpest transitions in Texas. One hundred twenty-five years ago, weary travelers who had successfully negotiated the treacherous rocky shelves and steep gorges of the pass—a journey that could take six heart-stopping hours—peered ahead into the afternoon sun to admire what seemed to be a huge and welcoming lake. But the waters were a mirage. And the journey ahead often proved more perilous than the one their tottering wagons had just completed.

Along the western edge of the Guadalupe escarpment lie the Salt Flats—playas and dunes formed by peculiar currents of the prevailing winds. Except for brief periods after heavy rains, the lake beds are dry; their deposits of salt glisten white and deceiving under the beating sun. Today’s travelers speed by with scarcely an indifferent glance, but the place they skirt so casually has shaped the life of this corner of Texas for hundreds of years.

The dry lakes themselves, the playas, are nearly sterile. Only simple crustaceans like brine shrimp, lying dormant through long dry spells and bursting forth into frenzied activity after a rain, can survive their dense concentrations of desiccating salt. Fringing the playas are sloping basins of pickleweed and grasses. Beyond them soar range upon range of dunes, upswept patterns of powdery white gypsum and fine red quartzite sand. This is the quintessence of desert.

The sand grows coarser as the land closes upon the Guadalupe range, grading into typical southwestern bajada country, riven with arroyos that are choked with shrubs. The great bluffs and mountain peaks rising steeply in the background separate this stark landscape from the cool, well-watered highlands of McKittrick Canyon, with its maples and madrones, its alligator juniper and rainbow trout, just fourteen miles away.

The quest for salt as a condiment and a preservative has been a persistent thread of human history. At least one thousand years ago, primitive hunters and gatherers frequented the Salt Flats. Their campsites have been found in more than four dozen places along the shores. Mescalero Apaches, who may have considered the salt deposits sacred, used them regularly. When the focus of the Spanish empire shifted southward to El Paso del Norte after the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, two governors dispatched expeditions to find the fabled beds of salt. That both should have failed is a measure of the remoteness of the country, the inhospitability of the desolate land, and the unyielding menace of the Apaches. Though the Salt Flats’ existence was well known by word of mouth, not until the 1740’s did their location appear on maps. And despite their lavishness—in places the deposits lay six inches thick along the surface, pure salt—the profits impressed many adventurers as hardly worth the risks.

Those who came had no incentive to linger. They shoveled up as much salt as their wagons could bear and creaked warily back to the safety of El Paso. Few, it seems fair to assume, paused to explore the mysterious solitude of the adjacent dunes. Like a changing, changeless river, these dunes are now as they were then: building, unbuilding, and rebuilding themselves invisibly to the eye. Their sweeping Moorish curves, their ridges sharp as scimitars, the ribbed patterns on the surface of the sand, seem almost sanctified, the placement of each single grain dictated to perfection by the wind. Their abstract beauty testifies to the driving geometry of nature.

The barren despoblado of western Texas was for generations the most stubborn obstacle to travel between San Antonio and El Paso. Searching for a safe route, Major Robert Neighbors led a party eastward in 1849 from El Paso through Hueco Tanks, the Salt Flats, and Guadalupe Pass. Gold seekers bound for California soon adopted the route. The Salt Flats entered upon their one fleeting moment of glory as a pathway to the Pacific. By 1853 regular traffic passed along the Neighbors trail, even though whole parties sometimes became stranded in the waterless reaches near the flats. By 1858 the John Butterfield Overland Mail Company had instituted stagecoach service on this, the Ox-Bow Route. But within a year Butterfield, frustrated by Indian attacks and the risks of travel through the arid country, moved his line south. The glory had lasted less than ten years.

Never again would the passage through the Salt Flats and Guadalupe Pass hold such significance. Mostly it was a way strewn with hardships, the kind of place where travelers stopped to add stones and a prayer to the simple trailside graves of others who had gone before. But it had the exhilarating freshness and purity of newly opened land. No doubt many felt the same emotions as John Russell Bartlett, the first boundary commissioner, who watched a sunrise on Guadalupe Peak in 1850 and wrote in awe, “No painter’s art could reproduce, or colors imitate, these gorgeous prismatic tints.”

The Salt Flats figured one last time in the affairs of West Texas. Under Spanish law, their deposits had been deemed held in common for the use of all; when in due course under Texas law the land was acquired by private owners who proposed to charge a fee, conflict broke out over the disposition of the salt. Eventually it exploded beyond the issues of immemorial custom versus private rights and engaged El Paso politics, racial animosities, and federal troops. The Salt War of 1877 was the climactic moment in the history of the Salt Flats. Within six years afterward, the Indians had been driven into submission, the railroad had gone through, and commerce flowed safely across the despoblado. The unique value of the Salt Flats was at an end. Having supplied a vital resource for as long as men had known of them, they became abruptly inessential. Ours is the first century in which men can pass them by, indifferent.

Today the Salt Flats show the scars of human contact. Heavy grazing in the bajada has altered the balance of the soil, allowing creosote bush to infest the area. Sport riders on motorcycles churn up the dunes for weekend amusement. But the basic elements are unchanged: fierce extremes of temperature (ranging from 105 degrees to minus 2 degrees) and of precipitation, which comes in torrents when it comes. Among the white gypsum dunes some plants of limited distribution survive, including the gyp daisy, the pitchfork, and Warnock’s groundsel, and unusual white lizards like Holbrookia maculata can be found.

Overshadowed by the sheltering mountains, the flats no longer exert the magnetic attraction that drew numberless generations to them. The surrounding land can no longer be regarded as pristine. But the haunting dunes remain, images outside of time.

Mountains

The Quitman Range

Angling broadly southeastward from the Hudspeth County seat of Sierra Blanca, Red Light Draw divides the Eagle Mountains from the Quitman Mountains like a dry sea bed between two continents.

Tradition says the draw was named for the signals affixed to its windmills many years ago as an aid to aircraft navigation. Earlier travelers doubtless would have welcomed an airplane as the only sensible means of crossing this uncharitable Chihuahuan Desert. Stagecoach companies like Butterfield and Jackass Mail left the draw and sought the relative safety of the river at the first usable pass—a place now known as Quitman Gap but called then, with both more poetry and more exactitude, Puerto de los Lamentos.

The “pass of lamentations” has not changed in a hundred years. It is the sort of place one would take a European visitor who asked to see the real West, not the West of Hollywood imagination. Its scale is modest. The high peaks are set far back, and the winding trail hugs the contours of the earth, rising and falling deceptively among low, knobby hills. Yucca and cactus loom on the rocky slopes like standing Indians. Afternoon shadows gather early. The air breathes ambush.

By 1859 Quitman Gap had succeeded the Salt Flats as the riskiest section of the rerouted San Antonio–El Paso road. A small post near the river, Fort Quitman, was garrisoned intermittently and ineffectively until 1876, when it was reduced to a stage stop. Apache skirmishes persisted in the Quitmans after such hazards had become but a memory elsewhere. In the summer of 1880 a stagecoach carrying a retired general, J. J. Byrne, was pursued for five miles through the pass. The carriage was left with twenty bullet holes and the general with an unenviable niche in the history books as the last passenger killed by Indians in Texas.

Downstream from the meager remains of the shabby fort, the Quitman range verges diagonally ever closer to the Rio Grande, tapering to a cul-de-sac at Indian Hot Springs. The range intrigues geologists for its contrasts. The northern end is a granitic moonscape of Tertiary igneous rocks; the southern is jagged and deep Cretaceous limestone.

The river below the hot springs is a surprisingly languid place. Sunlight dapples the water beneath thickets of salt cedar. Surrounded by the buzz of insects, hearing the occasional splash of a fish, watching the myriad ants busy themselves alongside fallen logs, one can imagine this to be the tropics rather than the nearly rainless desert that lies beyond the trees.

Farther on, the river swirls into the shallow, bubbling rapids of Mayfield Canyon. This reach of the Rio Grande, from Fort Quitman to Presidio, has always been reckoned its least consequential part. When the first Spanish explorers, Chamuscado and Rodriguez, struggled through the difficult terrain in 1581, they encountered a few Indians using the riverbank seasonally, but no farm villages. The river was too untrustworthy for that. Until its flow was controlled by dams in 1915, prolonged dry spells were broken by all-consuming floods. Mexican pioneer settlements founded in the 1820’s dwindled steadily until, by 1880, the valley near the Quitmans was again unpopulated.Farms introduced after the construction of the twentieth-century dams have followed the same bleak cycle of decline: because of upstream irrigation and El Paso’s municipal demands, the river reaches Presidio (if at all) carrying one-tenth of its pre-1915 flow. In 1902 it averaged thirteen feet deep above Presidio; by the eighties, a mere three feet.

Even this shrunken river may soon disappear into a man-made trough. The International Boundary and Water Commission, discomfited by the Rio Grande’s tendency to meander without regard to lawful borders, has begun to dredge 170 miles of river between Presidio and Fort Quitman. And the wild solitude may be broken for good if petroleum is discovered in the Texas Overthrust, a geologic formation encompassing the territory from Candelaria to Sierra Blanca, now being mapped and poked by optimistic speculators.

At least until the overthrust erupts with oil, the most noteworthy site in the Quitman Mountains is the set of six thermal pools known collectively as Indian Hot Springs. Their reputation for curative powers made them fleetingly popular as a health resort in the 1930’s. Frank X. Tolbert, the dean of modern-day Texas explorers, has been visiting the springs for more than thirty years and records that they have entertained such politically diverse bathers as Pancho Villa and H. L. Hunt. Hunt bought the property in the 1960’s, and although it has since changed hands, there is evidence of his attentions in the cottages, the ghostly and unoccupied thirteen-room hotel, and the covered enclosure for the most important pool.

One visitor, though, paused at the springs for something more than a leisurely medicinal soak. The Apache chief Victorio camped there during the final furious twilight of the Texas Indian wars, following a battle with a detachment of Buffalo Soldiers, the renowned Negro cavalry troops who bore the brunt of responsibility for protecting the borderlands against Indian depredations. Some say the soldiers got their name from the buffalo skins they wore; others say their appearance reminded the Indians of buffalo. One group, returning to their base at Fort Davis from a week’s patrol along the river in 1880, was surprised at dawn by Victorio’s followers on a hill above the springs. Their fate is one of the enduring legends of the Quitman Mountains.

The soldiers desperately piled together a redoubt. It can still be seen: a low semicircle of rocks, 27 feet wide, 18 feet from back to front, open at the rear where a steep hill afforded natural protection.

At this spot the Buffalo Soldiers made their stand. It is said that the Apaches approached them patiently, rolling boulders ahead as shields. Here and there in the gravel a spent cartridge lies, touched by no other hands since a doomed soldier placed it in his rifle. Five of the six were killed; one escaped. As if to hold back the force the soldiers represented, the Apaches drove tent pegs through the bodies of the dead.

Who were these six, and what must they have thought under that broad sky, in this barren place, cornered? It is fair to suppose that some had been born to slavery and could remember other ways in the black-earth Delta or the cool Shenandoah. Some perhaps had heard tales of lives in the green West African savannah. The unfolding of generations had brought them far from familiar things to die alone in this inexplicable desolation.

The ground on the hill being much too hard for graves, the Buffalo Soldiers were buried in a low alluvial wash beside an Indian spring. Their grim cairns, unmarked and angular as coffins, were layered with mortar to secure the rocks against the elements; but the wind and sun have had their way, and the mortar does not hold.

For the Apaches the victory was transient. Within months they were defeated forever, and the railroad clanged down on the pacified land at Sierra Blanca. Exactly three hundred years after the first curious Europeans had appeared there, the contest for the land was over.

Another hundred years, and portions of the river and the mountains are much transformed by man. The fine thick grama grass that once covered the hillsides is gone from the lower slopes; in its stead are the motley shrubs that follow overgrazing. Prolific salt cedars, purposely introduced from abroad for erosion control, have attracted white-winged doves to a region that was foreign to them just forty years ago. Even the bullfrogs and the carp are newcomers that would have been unfamiliar to a cavalry patrol.

In three centuries the Quitmans passed from savagery to conquest. In the fourth they were secured by the civilization of which they had become a part. These years were witness to the ebb and flow, ceaseless and continuing, of peoples across the face of the earth. For a thousand years before 1581, the customs, techniques, and forms of thought of those who lived here could have been recognized by their ancestors or their descendants ten generations removed. But no longer: today the Quitmans are a minor annex of an altogether different culture, and those who live here possess more kinship with the mind of distant Europe than with the lost mysteries of Jumano, Patarabueye, Apache, or Comanche. The history of the Quitmans seems unremarkable only because its central fact is the same as America’s central fact.

How did Europe come to Red Light Draw? What keeps it there? Riding homeward along the dusty road, one is prompted to consider how civilizations seed themselves in distant places, taking root in some and withering in others. Four hundred years have severed Red Light Draw from the world it had known immemorially, sealing it to another whose roots twine through Latin odes and English meadows. Can it thrive there, in land so harsh that mortar does not hold?

Griffin Smith, Jr., wrote about other forgotten places in the July 1974, August 1975, and April 1977 issues of Texas Monthly. These pieces and accompanying photographs by Reagan Bradshaw will appear in Forgotten Texas: a Wilderness Portfolio, to be published by Texas Monthly Press this fall. Smith and Bradshaw’s work was sponsored by the Natural Areas Survey Project at the University of Texas and the Texas Conservation Foundation.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads