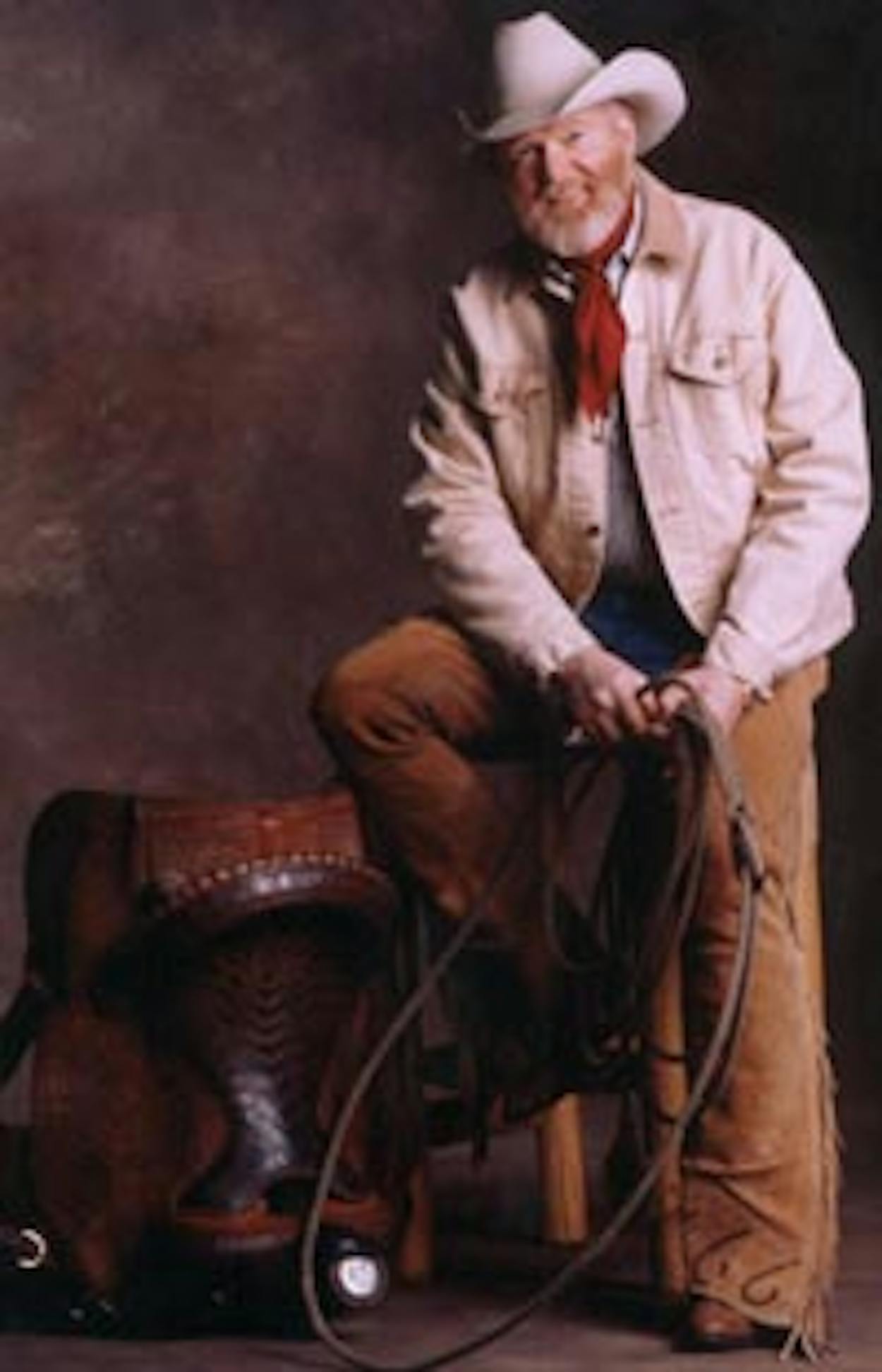

Between his travels and a recording session, Fort Worth cowboy poet and musician Red Steagall talked to texasmonthly.com about the cowboy way, his music, and his poetry.

texasmonthly.com: Well, sir, Baxter Black told me you were primarily a songwriter and then you decided to go into cowboy poetry. And so I was wondering how that transition happened?

Red Steagall: I realized one night that I was throwing good ideas away because they wouldn’t make commercial songs. I have been recording since ’69, and so I needed a steady stream of songs for my own records. Plus I like to write songs that other people like to record, so when you do that, you concentrate on whether it is a commercial song or a commercial idea. One night I realized that I was throwing away all of these wonderful ideas that I would never get back, and I made a promise that I would never do that again. So I kept all of those ideas, and then when the first cowboy poetry gathering came along, in Elko [Nevada], I went out there, and all of sudden I realized that that’s where my thoughts belonged. Really I had been writing poems forever, but I just put music to them.

texasmonthly.com: Well they are very tightly connected, aren’t they?

RS: Yes. If I start an idea, it will tell me if it wants to be a song or a poem, though.

texasmonthly.com: Oh yeah, how does it do that?

RS: The subject matter—whether I need to expound on an idea. With the kind of records I am doing now, I can use those longer form songs that tell a longer story, but in commercial radio, you have to capsulize everything into a few lines. So I love poetry. I love to write the poetry and let my stories tell themselves.

texasmonthly.com: How do you define cowboy poetry?

RS: Cowboy poetry is an American art form about a group of people during a particular period in the history of mankind, and it all started in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, when we were lamenting the passing of the West because we had fenced off the range. The cattle drives were over, and the life of the cowboy as he knew it then was gone, and he thought that the cowboys were gone forever so he started writing poems and songs about that lifestyle. Cowboy poetry originally began with the Scottish, Irish, English, and Welsh settlers who came west with the cattle herds, and they brought with them a love of poetry from the old country. As they settled into life here, they started writing songs and poems about their life in the New World. That trend continued until about 1937 or so, and then there were a couple of generations when there were only a handful of poets that published their work. Henry Herbert Knibbs published his first book in 1914 and the last one in 1930. Jack Thorp published his first book in 1908. Badger Clark was a part of that scenario also and then Bruce Kiskaddon and S. Omar Barker between say 1928 and 1954. And then the world changed; everything changed. People were still writing poems and still writing about the cowboy way of life, but they didn’t necessarily publish them until after the Elko gathering in 1985. But everybody realized hey, this art form is still alive. I remember one guy. He got up onstage, and he was crying. He said, “I thought I was the only person in the world who wrote cowboy poetry,” because it just wasn’t a part of the public consciousness at the time. People would write poems and put them in a shoe book and put them on top of the shelf in the closet and the grandkids would find them after they were gone.

texasmonthly.com: Do you think that cowboy poetry’s purpose is to sort of entertain people as well as to pass on the values that are intrinsic to the cowboy and a way of life? Or is it something else?

RS: I don’t know that anybody really starts out writing poetry with a mission in mind. I think that it is important to all of us who love the lifestyle to do whatever we can to preserve it because as our society changes, the perception of the need for the cowboy way of life diminishes to the general population. They don’t know where beef comes from. They think it comes wrapped in a piece of plastic in a grocery store. They don’t understand nor take the time to think about the lifestyle that produces that particular piece of meat. So as the public consciousness diminishes about the cowboy way of life, it is important that those of us who write protect the heritage and tradition and values of that way of life.

There are several things that created that way of life. First of all, I find that the people we write about are not Hollywood cowboys. Hollywood took those real life stories and sensationalized them and made them palatable to people all over the world. I did a story with a French journalist and he said, “Well, cowboys are not nice people. People in Europe refer to your president as a cowboy president. That’s not a nice connotation.” I said, “Why not?” He said because cowboys are not nice people. And I spent about thirty minutes trying to convince him otherwise. I don’t know that I did. The Hollywood version of the cowboy is a two-fisted, hard-drinking, hard-fighting, devil-may-care human being who shoots whenever he takes a notion to.

The people that most of us write about are those hard-working, honest, God-loving, dedicated family people who are loyal to the man they ride for and who have tremendous integrity. Those are the people who live with the land and live with the livestock, and they are the most wonderful people on the face of this earth. They are well-grounded, and that attitude started before there were any fences, before there were telephones, before there was television and the only line of communication was one line rider giving the day’s news that he had heard to the next guy even though it was distorted. If a guy was a liar, a thief, or a cheat, his reputation would precede him to the next cow camp and he couldn’t get a job. He was welcome to lay out his bed that evening and have a hot meal but was expected to move on the next day. [The cheats and the liars] weeded themselves out of that [honest] population. All of the characteristics that we love that make a harmonious society are embellished and embodied in that particular livestock group of people. And they have passed those traits on down to their children and grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren until those same people run the ranches of the West. They know what their lifestyle is but they are not vocal about it. They don’t say, hey, look at me, I’m honest. They live by that code, and they are examples for their children and the people around them. And so I think as we write and record and perform, we all try to live that kind of life and be the kind of person that we talk about in our writings. That may be a little egotistical, but I really think that that is what we all try to do.

texasmonthly.com: So how did you go about starting to write songs and stuff? Was it just something that you always did?

RS: You know, I probably started putting rhyming lines together when I was in grade school, and then by the time I got to college, I had a little band and I was writing songs and playing rodeo dances. And then I went out to Hollywood in about ’65, and I spent about the next seven or eight years in the business end of the business—as a publisher, a songwriter, and a record executive, and then I started recording in ’69. I have been writing songs as long as I can remember.

texasmonthly.com: Now how do you approach writing a poem? Do you have to wait for an idea to come to you?

RS: Yes I do. I don’t write a little bit every day. I’m not a craftsman as such. I only capture the inspirations and put them down. I might be talking to some cowboys and riding. I go out for the spring roundup for a couple of major ranches. I’ll be riding along listening to a cowboy tell a story, and he may paint a picture that I can see in my mind and I can write it, or he might just give me one line and all of the sudden I see a different picture using that one line.

texasmonthly.com: What do you think is more challenging: songwriting or cowboy poetry?

RS: Well, I think they are both challenging—to make them emotional. Any of us who write can sit down and just put lines together that are in meter and then rhyme. The first thing in any art form is original thought. You can only write so many things about an old barn. You can only describe a horse bucking so many times or a stampede or a wreck. So original thought is the single most important factor, and then meter. So in order to write a poem that somebody else will say, “Oh, that just really reminds me of my grandfather” or, “Gosh I remember a story like that,” and they can put themselves in that situation—it’s very difficult to make it emotional. On the other hand, it is extremely difficult to take a piece of music and capsulate your entire story in just less than three minutes or so. It’s difficult to do that, and it takes a lot of time. However, the two most important songs of my entire career, I wrote in less than ten minutes. Sometimes they happen that way.

texasmonthly.com: Songwriting and cowboy poetry have always been connected in history, haven’t they? There have been people who have come and put poetry to music and vice versa.

RS: Yes. The most important one, D. J. O’Malley, wrote a poem he called “After the Roundup” and we call it “When the Work’s All Done This Fall” and it was printed in 1893 in the Stock Growers Journal in Miles City, Montana. And then somewhere down the line somebody put some music to that. Another one is called “Tying Knots in the Devil’s Tail,” written by Gail Gardner around the turn of the twentieth century, and you know, Gail didn’t put any music to it. Badger Clark put the music to it and Badger Clark got the credit for the song. He called it “Tying Knots in the Devil’s Tail” and Gail called it “Up High in the Sierry Petes.” So, yes, they have been connected, but not all poems make good songs and not all songs are emotional when you read them.

Music is an emotional art form as well as poetry and rhyming and meter. Something about them stirs the soul, and I wish I knew what it was. I’d bottle it and get rich, but the music sometimes will create the emotion on its own. One great example of that is the song “Faded Love” that Bob Wills recorded. The lyrics are beautiful, but you stir a tremendous emotion in people just simply by playing the music.

texasmonthly.com: How do you think that cowboy poetry is changing or is it changing?

RS: It’s not changing. The subject matter may change a little bit. For example, very few ranches hook a team to a chuck wagon and pull it out anymore in the spring works. They use pickups and trailers to haul their cowboys and horses around, but one fact remains: They are still working cattle. They’re still doing the same thing that they have been doing for one hundred and fifty years. They are doctoring, castrating, dehorning, branding, and doing all of the things to that livestock that they need to do to be a productive rancher and to protect their property. They are still doing the same job, so the poetry is going to be written about the same people doing the same thing. It’s just from a different viewpoint. Baxter writes mostly modern-day things. He writes very little from a historical viewpoint because he likes to know that it is being carried on. He likes people to know that what is happening today is real. Bill Owen, one of the greatest artists of all time, doesn’t paint historically. He paints what is happening today. He is preserving on canvas and in bronze what’s happening today. A lot of us live in the past. We like to go back and let our imagination run wild and think that we could have lived during that time period. Some of us write historic things, but basically it is all about working cattle, about riding horses, about handling horses, about the relationships between the men in that particular atmosphere.

texasmonthly.com: Does cowboy poetry differ in this state from the rest of the West?

RS: It is primarily the subject matter that varies and the way we look at the cowboy way of life. The way we work cattle and handle horses was directly influenced by the Mexican vaquero, the peasant, the guy who really did the work and got down in the trenches. The buckaroo has a California influence and that means that the California ranchers were the elite of the society and they handled themselves in a completely different attitude. The buckaroo likes fancy dress. He likes fancy equipment and he likes a lot of silver on his gear. That’s the California influence. The West Texas cowboy wants to know that his equipment is reliable and simple. That’s basically the way he looks at himself. But they are still doing the same job, and the California-influenced cowboy is just as adept at handling cattle as the West Texas cowboy, but the buckaroo might dally and the West Texas cowboy ties hard and fast to the saddle horn. There are a lot of differences in the way they do things, but they all reach the same point just as efficiently as the other.

texasmonthly.com: In Ride for the Brand there is a dedication to Carlos Ashley. I was wondering if you could tell me about his influence on you.

RS: Carlos Ashley preserved the image of the people of the Hill Country, the livestock industry, and the attitude of the society. He preserved it in rhyming form. Carlos Ashley was one of the finest gentlemen I have ever known in my life, and I didn’t meet him until he was way up in years. Baxter and I became infatuated with him. A fella in Austin sent me a copy of a little book that Carlos had done called That Old Spotted Sow and Other Hill Country Ballads and Baxter and I sat on my front porch one afternoon and read that entire book to each other. We just fell in love with the way Carlos put the stories together, and he became a very important part of our lives. I did get to spend quite a bit of time with him after I met him and before he passed away. He became a very, very dear friend and an important part of my life. I learned from Carlos how to make people come to life. I hope I learned that. That’s what I admire most about his writing—that his characters came to life. You knew them. They became part of your world. As you read the poem, you either fell in with them and rode that wagon with Blacksnake Bill, or you were in that bunch of guys playing brush poker when Aunt Cordie caught you, or you sat in the chair at Jim Watkins’ barber shop, or had a bowl of chili in Bob Sears’ chili joint, or you rode in those hills with Carlos and saw that old spotted sow and those ten baby pigs. He got you involved in what he was writing about, and I think Baxter and I both really admire that in his writing and I think it had an effect on the way we both write.

texasmonthly.com: Where do you think cowboy poetry is headed?

RS: People who love the lifestyle will continue to write about it. The world changes. The emphasis will be gone from time to time—off of the cowboy way of life. The cowboy is a romantic figure primarily because of the silver screen. The people who live in a cloistered society in the big cities who don’t see much green grass and don’t see much blue sky because of the buildings dream of being outdoors where they can see forever and of getting on a horse and riding into the sunset and of being an individual, being free, being independent. So as long as those images are important to people, the image of the cowboy will remain, but it may not have the same momentum it has now. The cowboy way of life was downplayed for about twenty years and then something like Urban Cowboy came along and got everybody wearing boots and hats again, not necessarily the working cowboy, the Hollywood cowboy. From time to time, generations ask where did we come from, how did we get to this point? And we got here with those values that make a harmonious society: honesty, integrity, loyalty, dedication, and conviction. All of those things that make a harmonious society are important. It doesn’t make any difference how fast-paced or high tech our society gets, those values, the values of common decency and respect and love for other people, are still the most important factors in any society if you want that society to be harmonious. Those are the things that we learn from the cowboy way of life. If the cowboy goes out of the public consciousness, cowboy poetry will take a backseat. We hope that doesn’t ever happen, but everything goes in cycles. And the people who are writing about the lifestyle will never quit writing about it. You just might not be able to buy their books or may not be able to hear their records on the radio.

texasmonthly.com: People have told me that since cowboy poetry has been spotlighted more than usual there have been a lot more people who have tried to come into the lifestyle and then do cowboy poetry. They come in from the outside. I was wondering if you have seen any of that, the concern being that these people don’t really know what they are doing.

RS: Anytime there is something that is new and exciting, something that is working—we saw the same thing happen to country music. Country music was primarily steel guitars and fiddles and talked about heartbreak and getting drunk and so on and then all of a sudden a fella named Garth Brooks comes along and breaks it wide open. It appeals to an audience that country music has never appealed to before. I could tell you several country stars who were rock and roll singers and became country stars, and then as a result country music moved more and more and more toward a soft-rock approach as that audience increased. Anytime there is something that looks good and has a public appeal, there are going to be people coming in from the outside to try to be a part of it. If you want to remain a purist and say that only working cowboys can write cowboy poetry, that’s foolish. I have grown up with livestock all of my life but I am not a cowboy. I don’t have the skills to be a working cowboy, but I do understand it and I observe it and I try to write factually about that lifestyle. You will find other people who don’t necessarily work as a working cowboy who are able to write about the lifestyle simply as an observer. Then there are a lot of people who want to write about it who don’t understand it and never will understand it and don’t have the heart for it. Those people won’t survive. They’ll weed themselves out eventually. I don’t know why anybody is worried about that because the best will rise to the top. If some people think that a person doesn’t belong in the genre, then that is their business. I mean they can have those thoughts if they want to, but my friend Buck Ramsey, who was a wonderful, wonderful poet, made a statement one time. Somebody said, “Are you a cowboy?” and he said, “You never are a cowboy until somebody else says you are.” In other words, you don’t brag on your own accomplishments or your own talents. If somebody says, “Yeah, he’s a good hand and he can handle a rope and handle a horse and knows cattle” than that is the compliment you are looking for—for somebody else to say, “Yeah, he’s a good hand.”

texasmonthly.com: Bette Ramsey told me to ask you about Buck Ramsey.

RS: He was one of the most unique people I have ever known. Buck, in my estimation, was a literary genius, and he channeled his talents in a lot of different ways. But his true calling was as a poet and as a chronicler of the lifestyle of the American cowboy. He loved it so much and he was such a part of it because he had the imagination to see what could happen. He had the objectiveness to know what does happen and the ability to put it all down in a proper form so it had emotion. He was a dear spiritual friend of mine—he and Bette both—and I just absolutely adore Bette. Buck was one of the greats and will be remembered that way forever.

texasmonthly.com: What’s it like to be up on stage when you are performing?

RS: It’s exhilarating and it’s rewarding to know that something you have written is being accepted by other people and that they get something out of it. That it either says something to them emotionally or they like the message or they like your presentation or something about what you are doing they enjoy. It’s a tremendous ego booster.

texasmonthly.com: Well, sir, is there anything that you would like to add?

RS: I am just deeply honored that you would call me.

texasmonthly.com: Oh, sir, trust me, the honor is all mine. I have been growing up in Dallas, hearing about you all of my life, so being able to finally talk to you is a pleasure.

RS: Well, thank you.