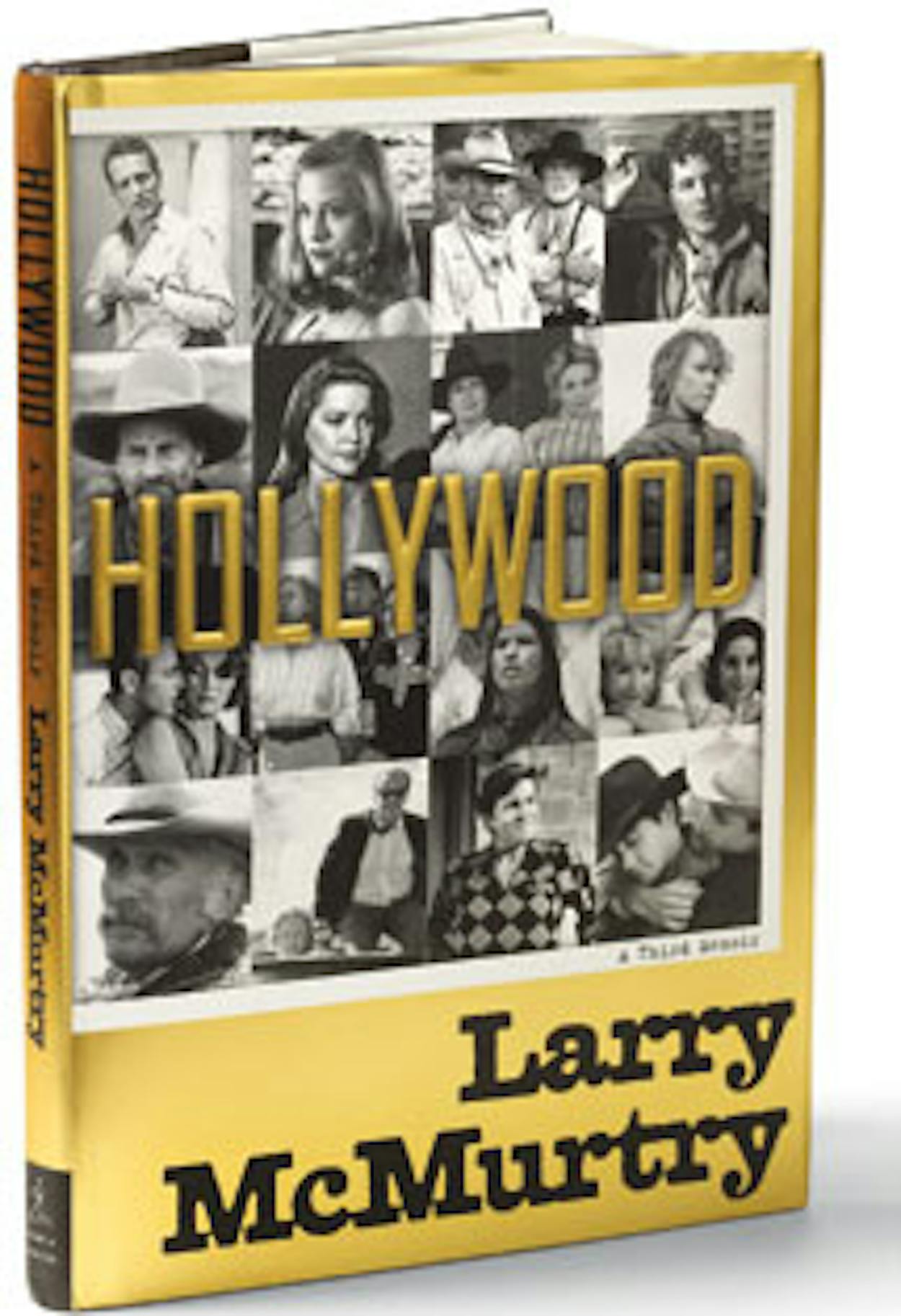

Larry McMurtry, and I know this for a fact because he told me so, is an avid reader of memoirs and autobiographies, especially of chatty Brits such as James Lees-Milne, whose twelve volumes of diaries McMurtry has perused several times, and Somerset Maugham, whose magisterial The Summing Up McMurtry read when he was starting out as a writer. But instead of publishing his own diaries (possibly nonexistent) or a single-volume memoir, either of which would constitute a major contribution to American letters and reveal something of his private life, McMurtry has chosen to take the three strands of his professional life and parcel them out in a trio of slender volumes. The last of these, Hollywood: A Third Memoir (Simon & Schuster, $24), is the least interesting, partly because McMurtry’s powers are waning—he has said so, and many reviewers, eager to pile on, enthusiastically agree—and partly because Hollywood isn’t all that interesting to those of us who aren’t celebrity-obsessed.

The first volume of the trilogy, Books: A Memoir (2008), details McMurtry’s lifelong obsession with reading, collecting, and selling books. Though surely appreciated by his peers in the rare-book trade, Books offers many pleasures for the rest of us as well. One is reading chapters in whatever order you like; since many of them are mere vignettes that don’t build on one another, chronology doesn’t matter all that much. The brevity may prove pleasing for the dutiful reader—I’ve done my job; I finished three chapters today—but it cuts both ways: Is this important? Can I skip it?

Still, Books manages to remind us that McMurtry is bookish in the best sense. He knows what’s good and what isn’t. There’s a marvelous little chapter on how much he enjoys going through the bulk purchases at Booked Up, his rare-book repository in Archer City, culling the dross from the gold. During a visit to his home in 2002, I received an indelible impression of McMurtry’s love of books: Three walls of one large room were filled with bookshelves stretching from floor to ceiling, and every lavish hardback in that collection dealt with the rivers of the world. He likes to read about rivers.

Following close upon the boot heels of that first volume, Literary Life: A Second Memoir (2009) moves swiftly through McMurtry’s college years to his precocious first novel, Horseman, Pass By, and then on through the many he has published since. Along the way he throws in brief anecdotes and opinions about his influences, including such Americans as Kerouac and Dreiser. But it is the Brits that he nominates as models for young writers. E. M. Forster and Evelyn Waugh, he notes, “seldom published an unclear sentence.” The same could be said of McMurtry, which is perhaps one reason he is overlooked in American academic circles; his character-driven novels lack the obscurantism of much post-realist fiction.

Literary Life is almost willfully impersonal. Anybody looking for juicy confessional material had best look elsewhere. Typical of McMurtry’s reticence is this remark about the inspiration for The Last Picture Show: “In the summer of 1964 a family crisis erupted in Archer City.” Most writers worth their salt would have taken this sentence and run with it. But McMurtry never tells us what the imbroglio was, only that it made him wary of Archer City and prompted him to write about the culture that had produced the crisis, not the crisis itself. One might be tempted to explain this reticence as a “Texan” thing, but that’s too easy. It may, though, be a West Texas Scotch-Irish thing. Or a male thing. In Texas it’s the women who spill the beans: Think of Mary Karr or Gertrude Beasley.

If McMurtry had wanted to write a big book about himself, Literary Life would have been the place to do it. His fans certainly have a mild interest in his book-collecting and his movies, but it’s the novels, especially those that are grounded in Texas, that they care the most about. This is the terrain that might have inspired McMurtry to dig in and offer some revelations about the man who created Gus McCrae, Aurora Greenway, and Duane Moore. But great authors write what they want to write, not what readers want them to.

McMurtry ends Literary Life with the sales pitch “Now it’s on to the big adventure that is Hollywood.” But the newly arrived Hollywood doesn’t deliver a “big adventure.” In this volume the strain of having disentangled the narrative strands of his life (leaving out almost altogether the fourth strand, his private life) begins to show as McMurtry is constantly repeating information he shared in the first two books or jumping around between undernourished digressions on producers, agents, actors, etc. In the past McMurtry has written brilliantly about film. His 1987 book Film Flam contains, for example, a devastatingly funny takedown of Lovin’ Molly, Sidney Lumet’s brokedick version of McMurtry’s second novel, Leaving Cheyenne. But such moments are few and far between here, and McMurtry’s refusal to dish leaves us with unsatisfying admissions like this one: “What [people] mainly want to know . . . is what Diane Keaton or Cybill Shepherd is like; it’s normal to be curious about them but they’re not going to learn anything from me.”

The short chapters, too, become a source of McMurtry’s sardonic commentary. Chapter 26, for example, consists entirely of 58 words and is a defense of short chapters. Chapter 46—a 57-word anecdote about the author Annie Proulx—ends: “Short chapter, sorry.” Perhaps we can look forward to a small volume of prairie haikus.

Hollywood is the thinnest and most scattered book in the trilogy, and it certainly engages in the most name-dropping, if only because movie directors and actors are much better known in America than literary sorts, and McMurtry has worked with an impressive number of them. So there are stories to tell, a few of them entertaining even to those who are allergic to Hollywood gossip. One highlight is a sequence about that much-maligned industry icon, the agent—in this case, the legendary Irving “Swifty” Lazar. McMurtry spends a fair amount of time expressing his love of Lazar’s old-school charm and penchant for expensive restaurants and custom-made British suits—all this despite the fact that Lazar’s eventual decline and inattention to detail allegedly cost McMurtry about $15 million.

McMurtry’s large-hearted sympathy for Lazar’s enfeeblement is hardly surprising to the attentive reader of these memoirs. One of the melancholy themes that runs through all three is the inexorable passage of time and the changes wrought by the decades. Each book is suffused with a sense of loss—of the old book-trading days, of friends and cultural values, of old Hollywood itself. There is, one suspects, another loss haunting these pages, that of McMurtry’s own ambitions as a writer. The result is something genuinely odd, though hardly without its charms: a three-volume memoir that offers little insight into the man who wrote it, a man who happens to be the most psychologically penetrating writer ever to come out of Texas.

TEXTRA CREDIT: What else we’re reading this month

Nashville Chrome, Rick Bass (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $24). A fictionalized telling of the story of the Browns, a chart-topping country act in the ’50’s and ’60’s.

Austin City Limits: 35 Years in Photographs, Terry Lickona and Scott Newton (UT Press, $40). Nearly three hundred images from the long-running television music series.

The Personal History of Rachel Dupree, Ann Weisgarber (Viking, $25.95). The tale of a black homesteader in early-twentieth-century South Dakota. Read an excerpt. Read an interview with the author. Buy it at Amazon.