This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

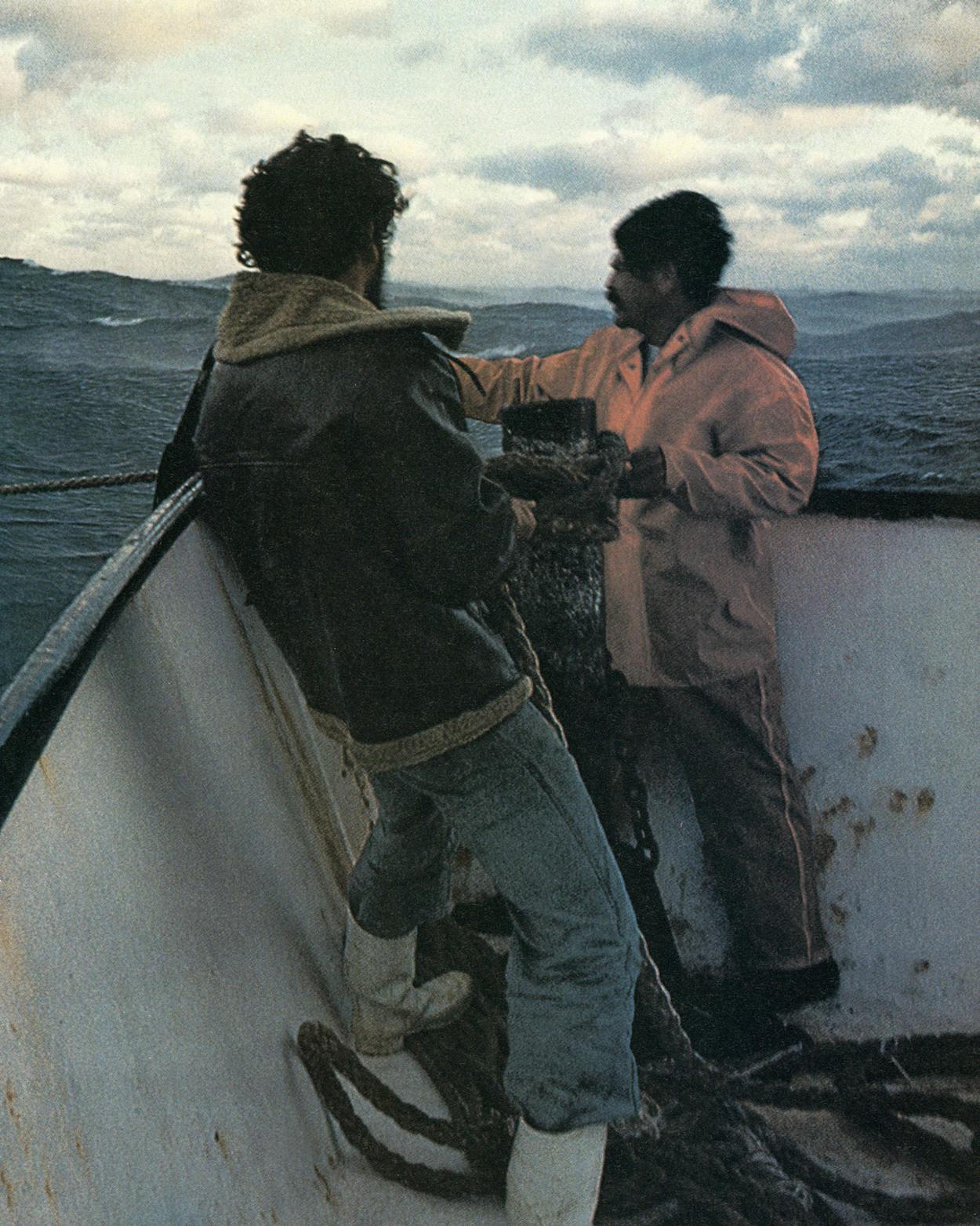

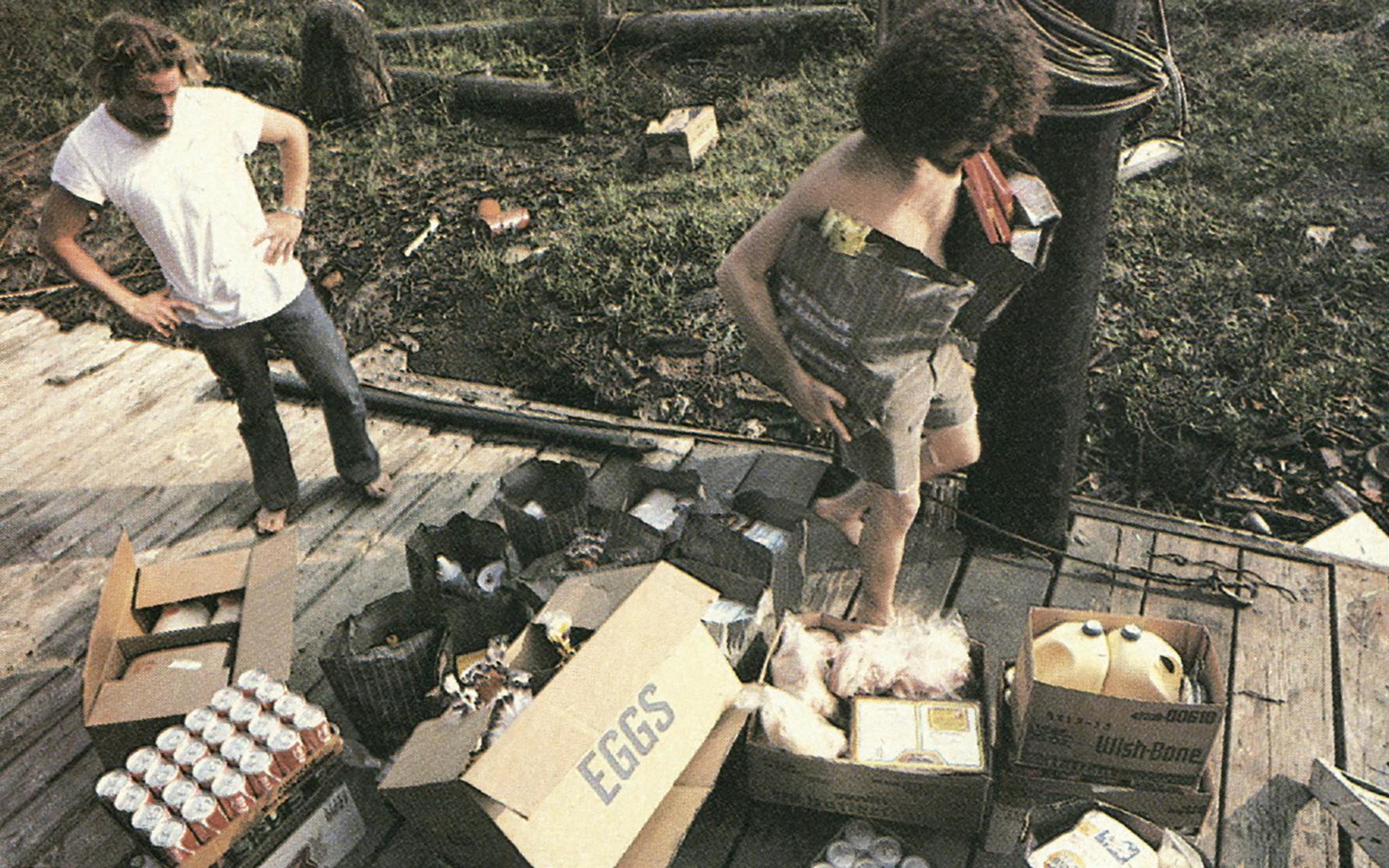

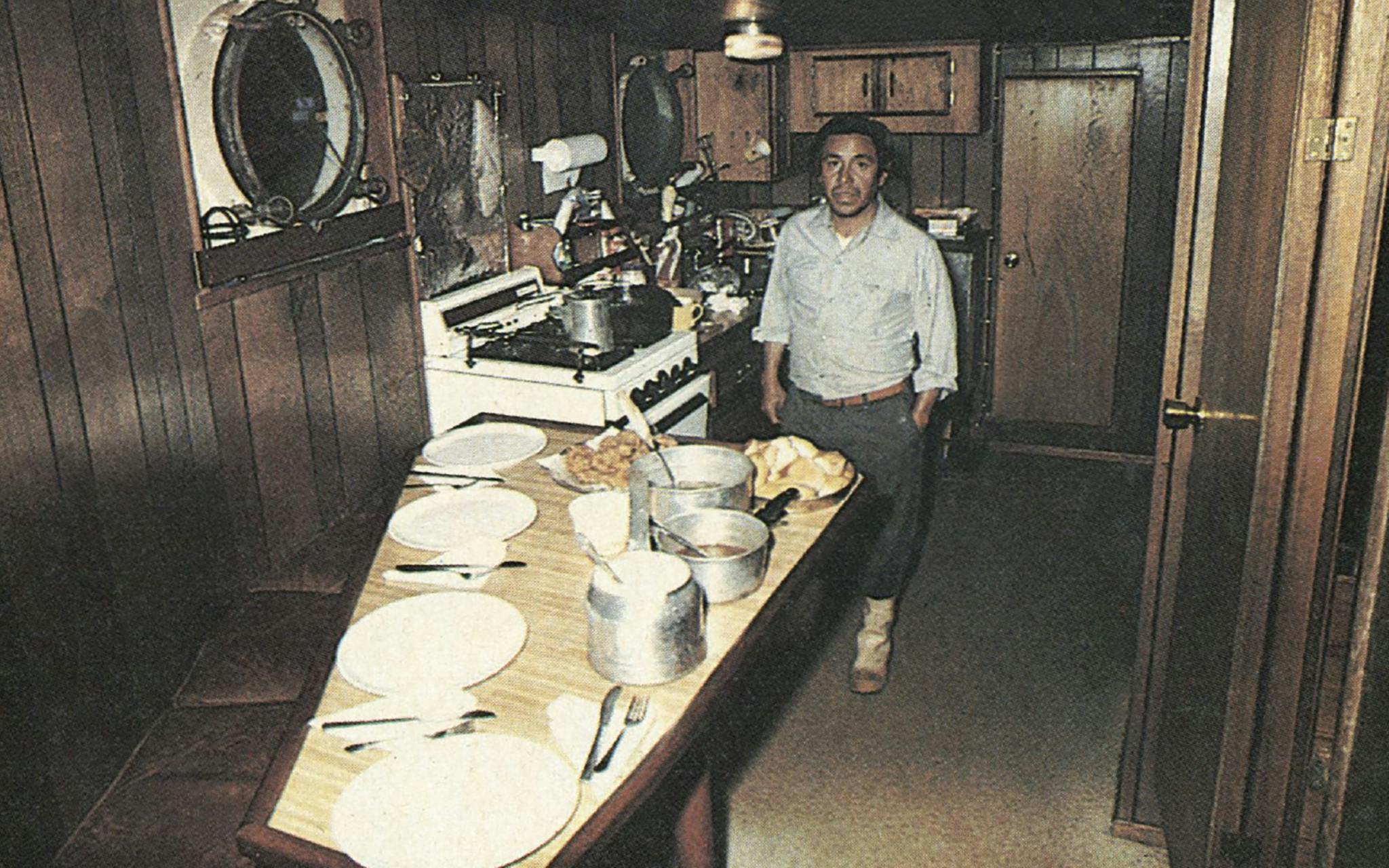

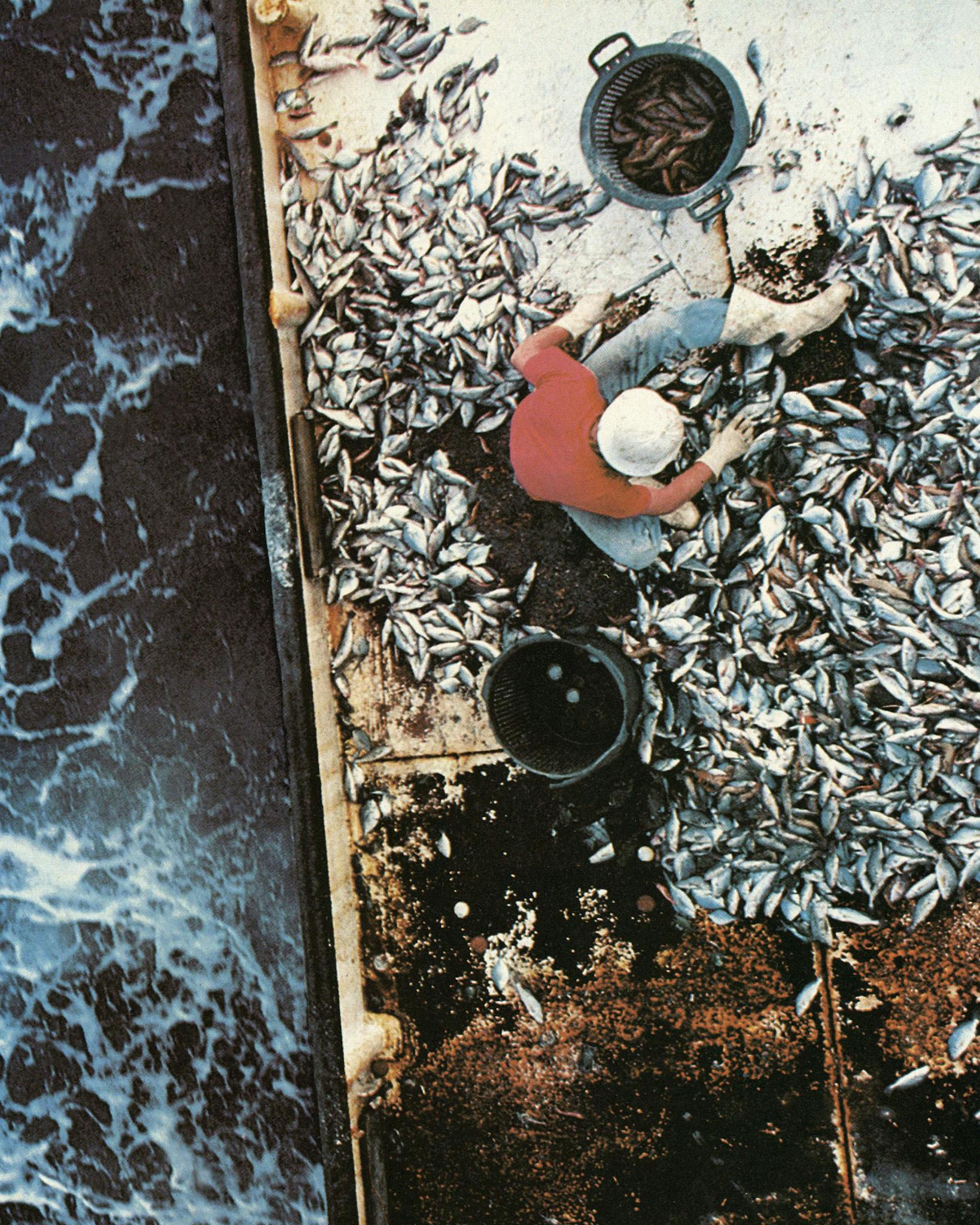

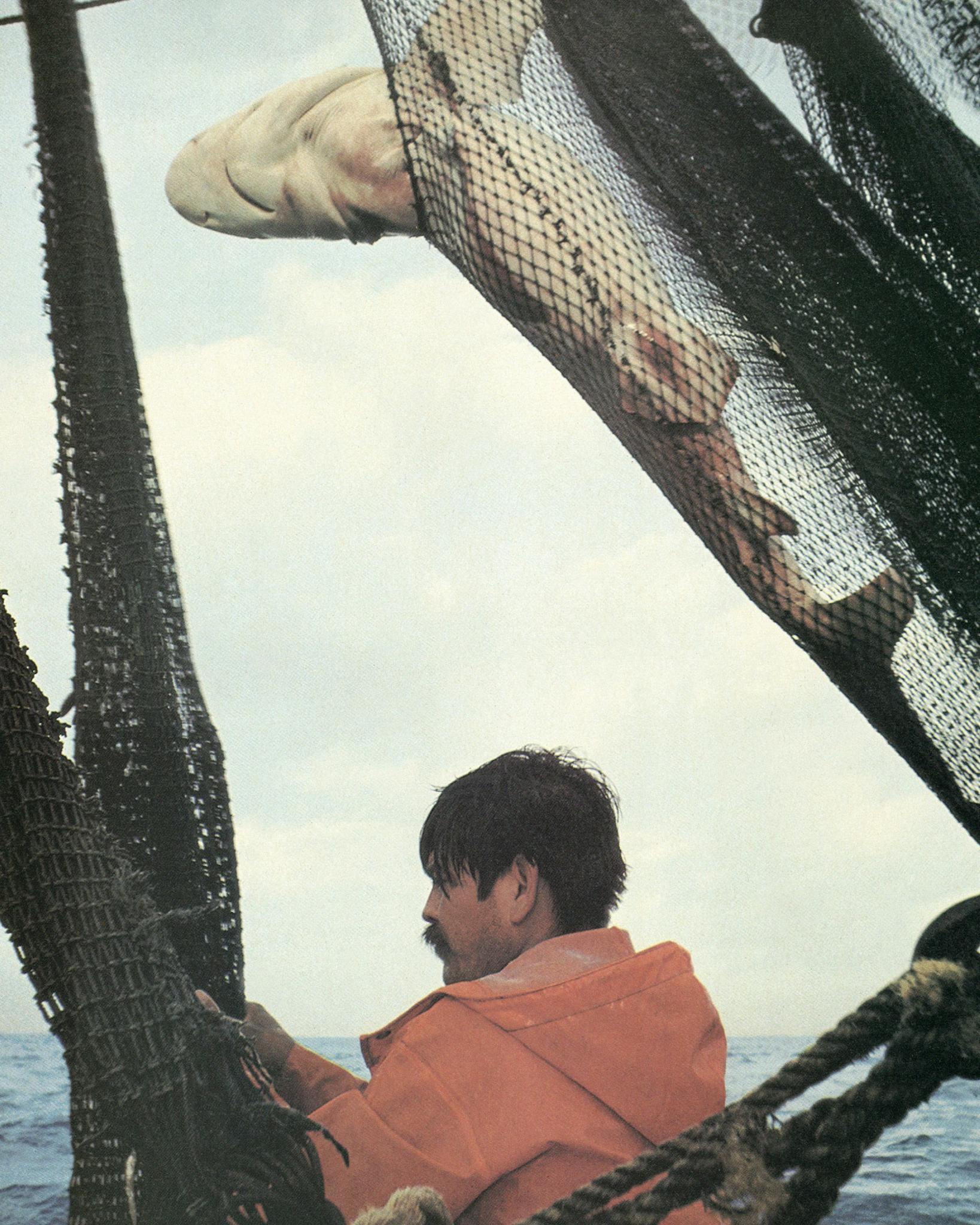

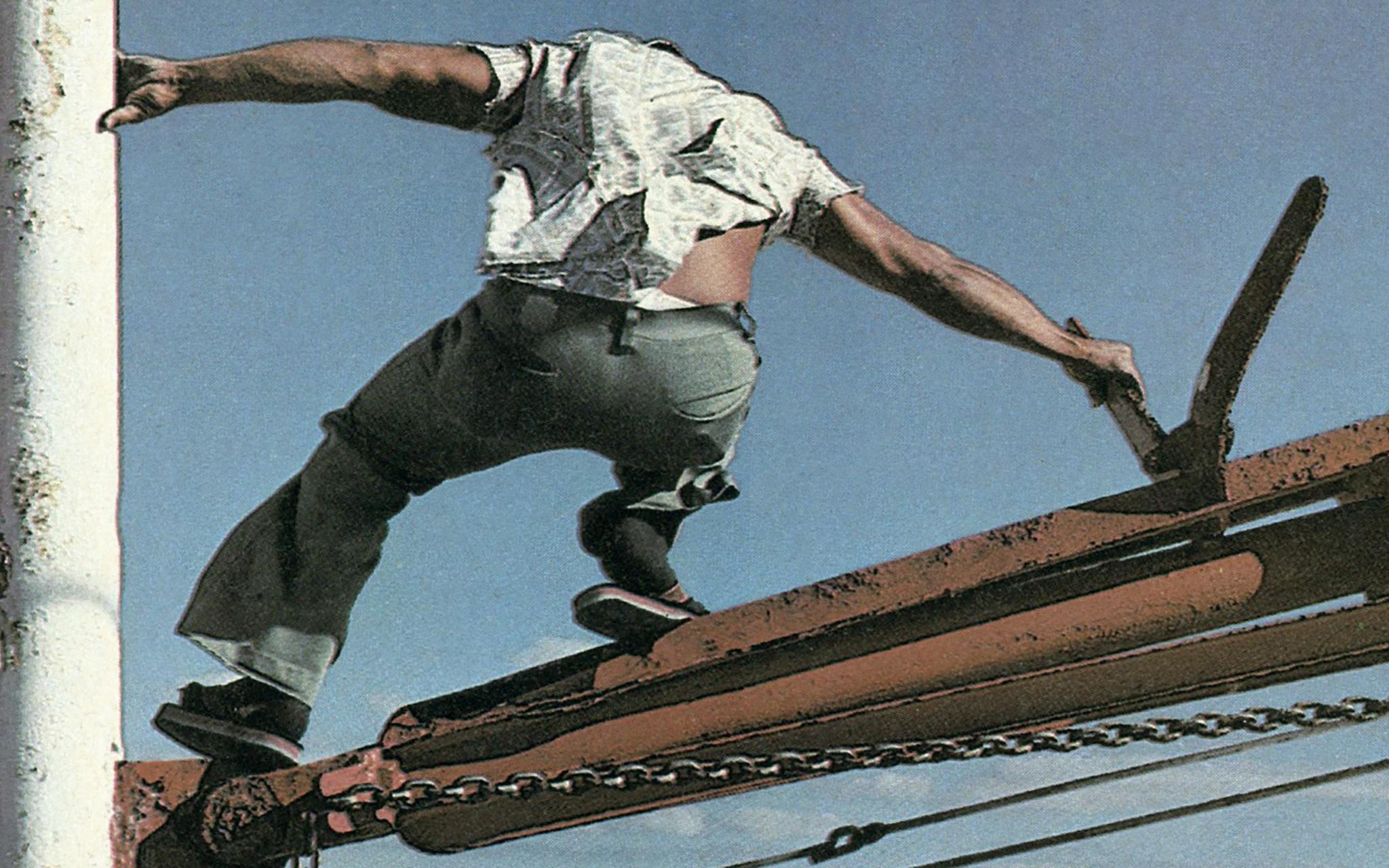

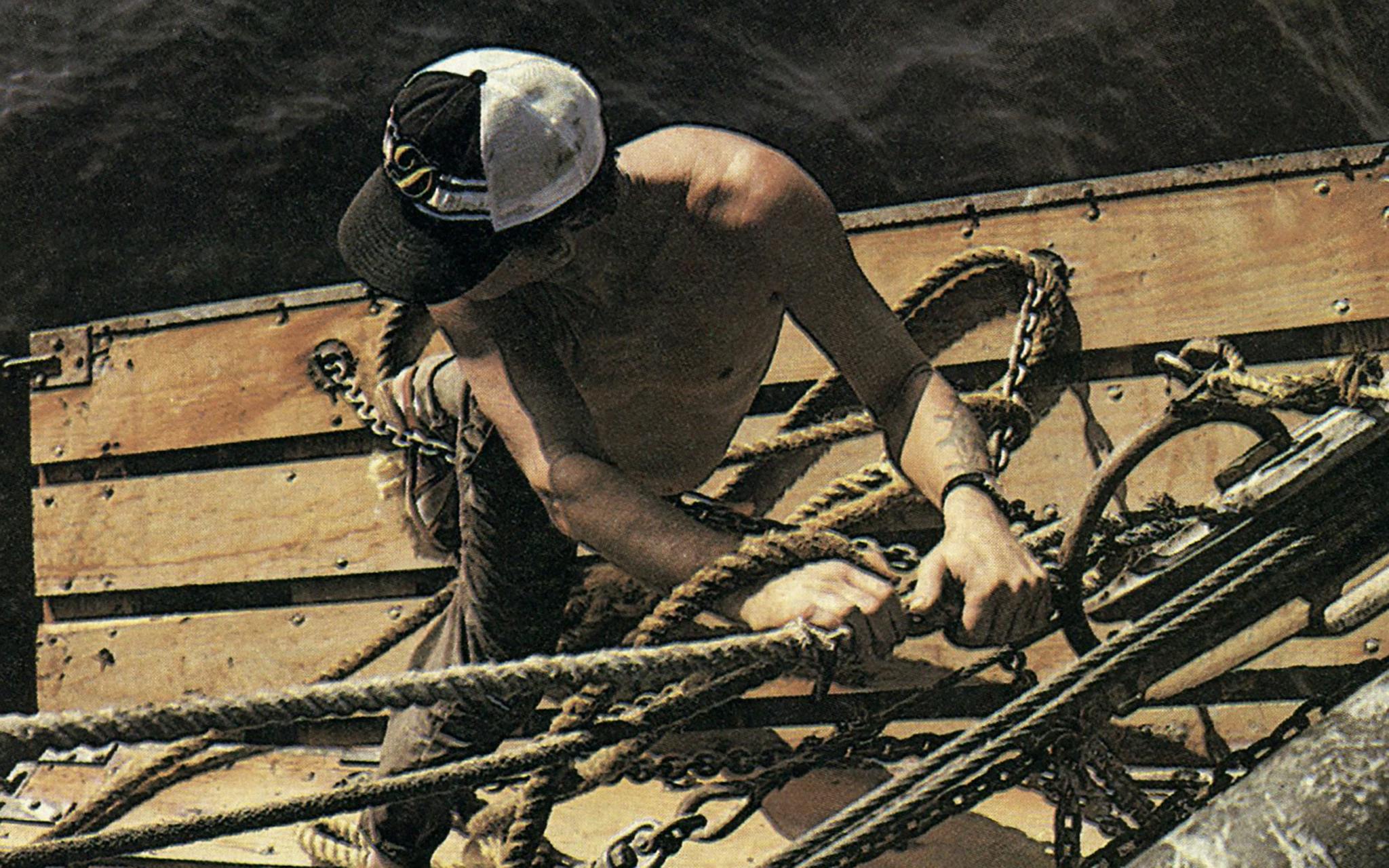

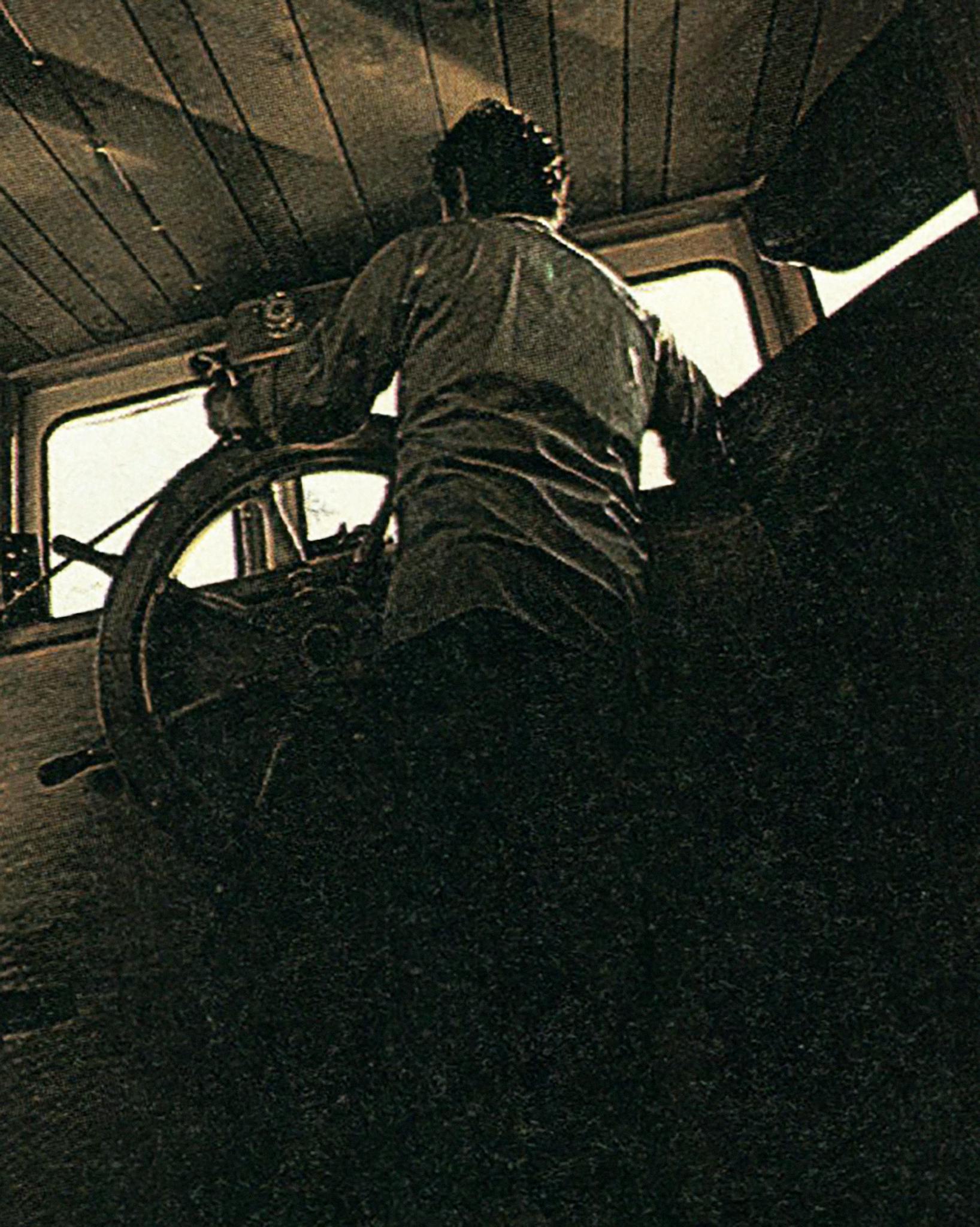

Shrimping in the Gulf has never been a calling men pursued for the fun of it—or for the easy money. Oh, there was plenty of money to be made once: the lowliest deckhand could return from a fifteen-day trip with $3000 in his pocket. But the work was brutal and, most of all, lonely: two or four or six weeks on a pitching boat in the middle of the hostile ocean. Shrimp are elusive creatures, apt to change their feeding grounds from year to year, and some years the shrimpers never quite figured out where they were. Those were years of frustrating summers and lean winters. And then in the good years the crew could work themselves near to death, hauling up the writhing beasts by the ton, working around the clock to get them decapitated and iced down before the sun had a chance to make them spoil.

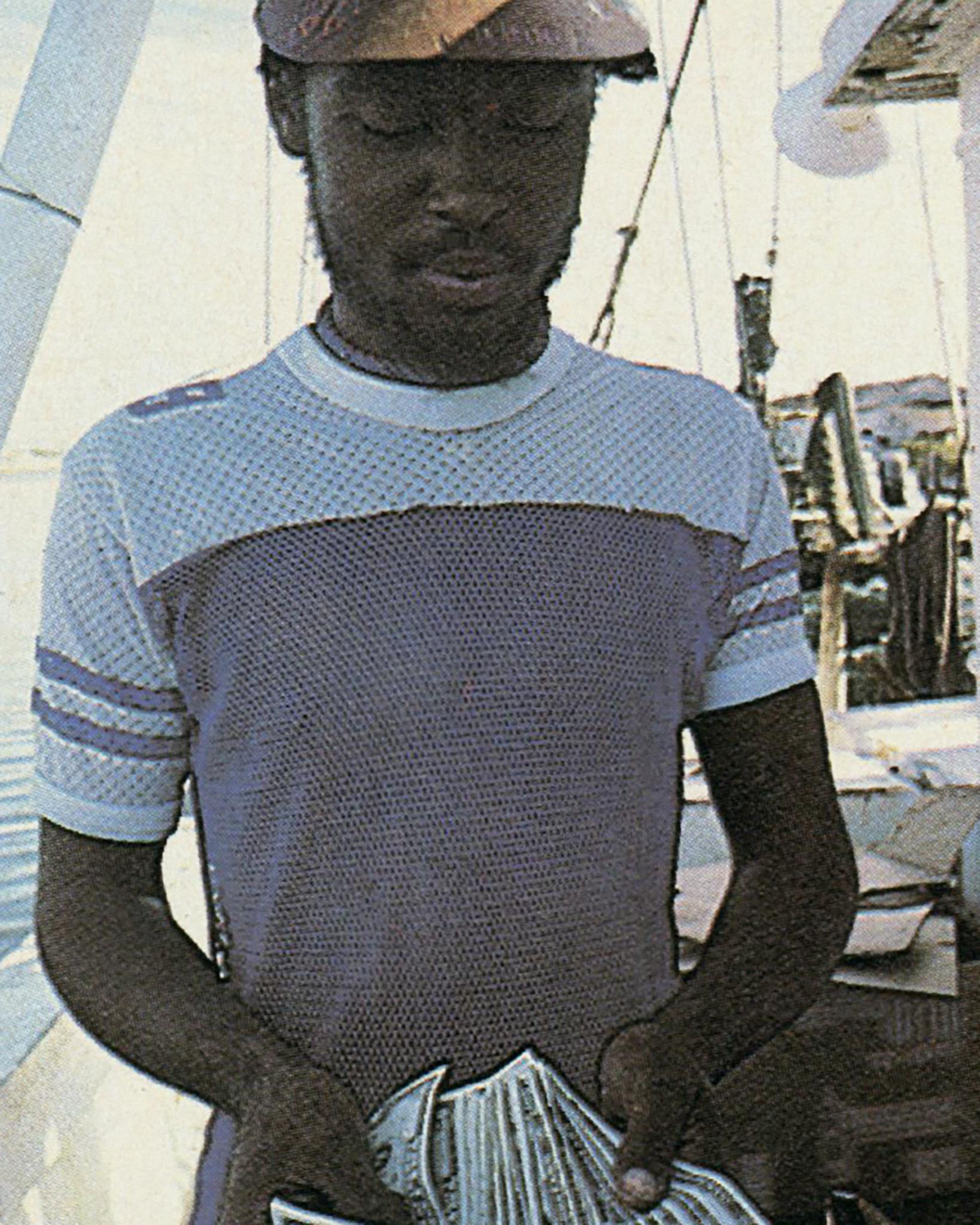

Now those flush times seem long ago. The Gulf has been particularly stingy the past two seasons—in some places the catches are less than half what they once were, forcing many independent shrimpers to the brink of ruin. Gulf fishermen are also caught between the Mexican government, which has slowly cut off American boats’ access to its rich shrimping grounds, and the bay shrimpers (including the newly arrived and much resented Vietnamese), who—the Gulf shrimpers say—are overharvesting the bays, where the crustaceans mature, so that fewer adult shrimp migrate into Gulf waters. Meanwhile, the cost of owning and operating sophisticated shrimping trawlers has risen sharply: a shrimp boat can cost anywhere from $250,000 to $600,000, and diesel fuel, which the boats burn at a rate of nearly twenty gallons an hour, is running $1.10 a gallon—up from only 15 cents eight years ago. And to top it all off, American shrimpers must compete with Mexican shrimpers, who export some 80 million pounds to the U.S. and who can still get fuel for 22 cents a gallon.

The results? Well, don’t expect to find any but the tiniest shrimp in your local fish market for less than $4 a pound; that’s the minimum shrimpers say they can charge and still make a profit. And you’ll probably find fewer of the creatures there at any price, because most captains have ceased shrimping in all but the most productive months (July to November). Instead, many boats are sitting idle, while others are being outfitted for long-lining, trawling for new prey such as swordfish. And many independent owners have sold out to huge agribusiness conglomerates better able to weather the rough financial waters.

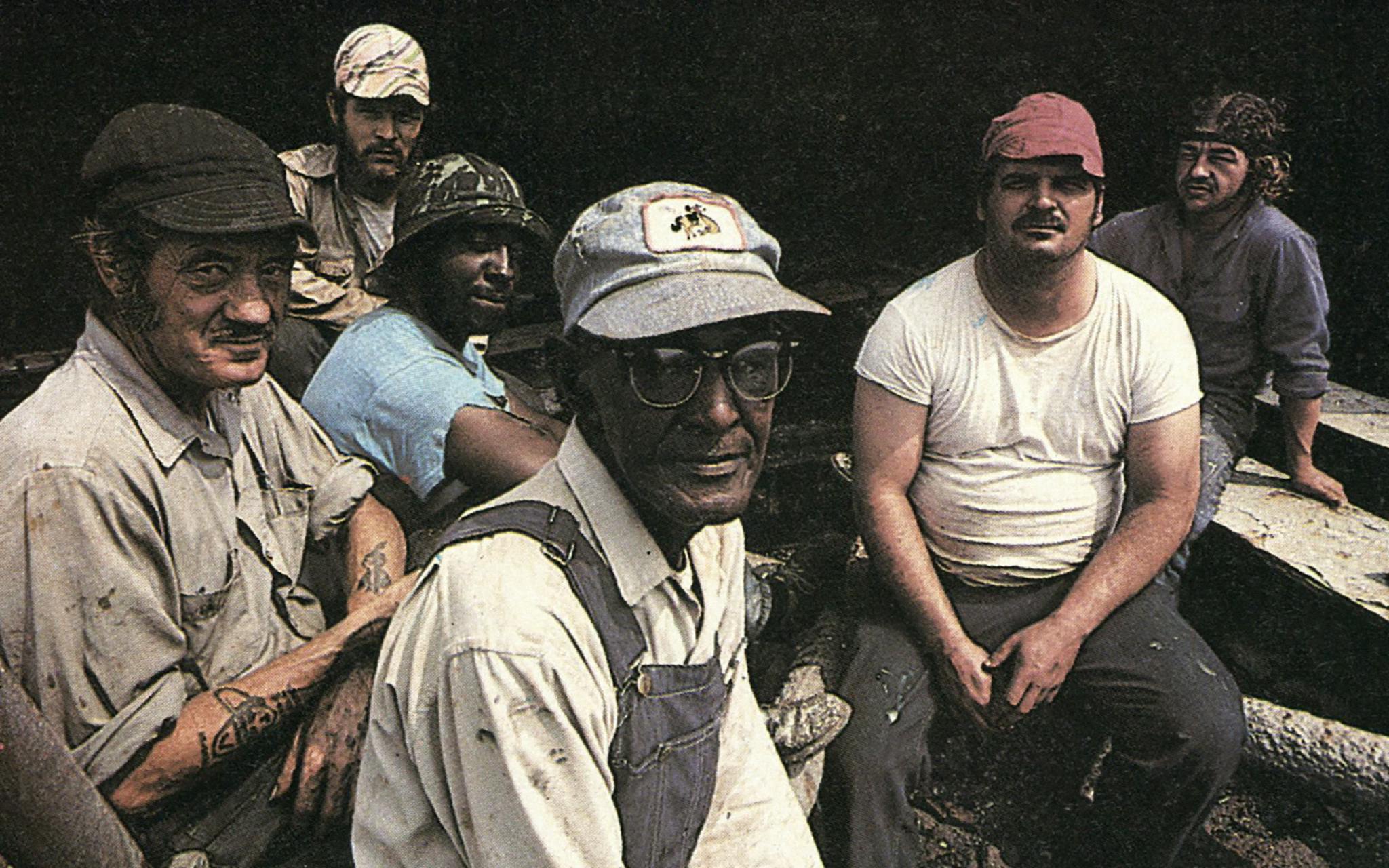

This trend, if it continues, could spell the end of the family-owned shrimp boat, and with it the end of a unique Texas subculture. The shrimpers inhabit a world of their own, with codes, superstitions, and rites—including the annual blessing of the fleet in April—whose origins are often lost in antiquity. And although shrimpers in most Texas coastal towns have coexisted amicably with their landlubber neighbors, they have always been a breed apart—hardier, more independent, freer. Shrimpers tend to their own; they see each other through bad times. Sons of shrimpers nearly always become shrimpers, and hard-won knowledge of the sea is passed from generation to generation. The seemingly easy banter between father and son or captain and deckhand conceals a constant process of teaching and testing—if you are to depend on the man beside you in your battle against the sea, you must know in advance that he can be counted upon. Against such an unrelenting adversary, a trustworthy ally is beyond price.

- More About:

- Hunting & Fishing

- Business

- TM Classics

- Shrimp

- Photo Essay

- Fishing