When I was about twelve, my mother took me on a pilgrimage to Neiman Marcus. This was in the pre-Southwest Airlines days, so we must have driven the five or so hours to Dallas from San Antonio and stayed overnight in a downtown hotel. We ate pecan-studded ice-cream balls in the Zodiac Room, and my mother bought me a dress in what you might call the milkmaid style—a beige apron over puffed calico sleeves—that was so tight through the bodice I had trouble breathing. It itched. It cost $36, which in the mid-sixties was an exorbitant amount for a girl’s dress. In retrospect, a garment modeled after something a farm girl would wear seems an odd choice for a San Antonio preteen bent on proving her chicness, but, like the price and the discomfort, the actual style of the garment was beside the point. I now owned something from “Neiman’s,” and with that one word became instantly intimate with all that was fashionable, sophisticated, and tasteful in the world.

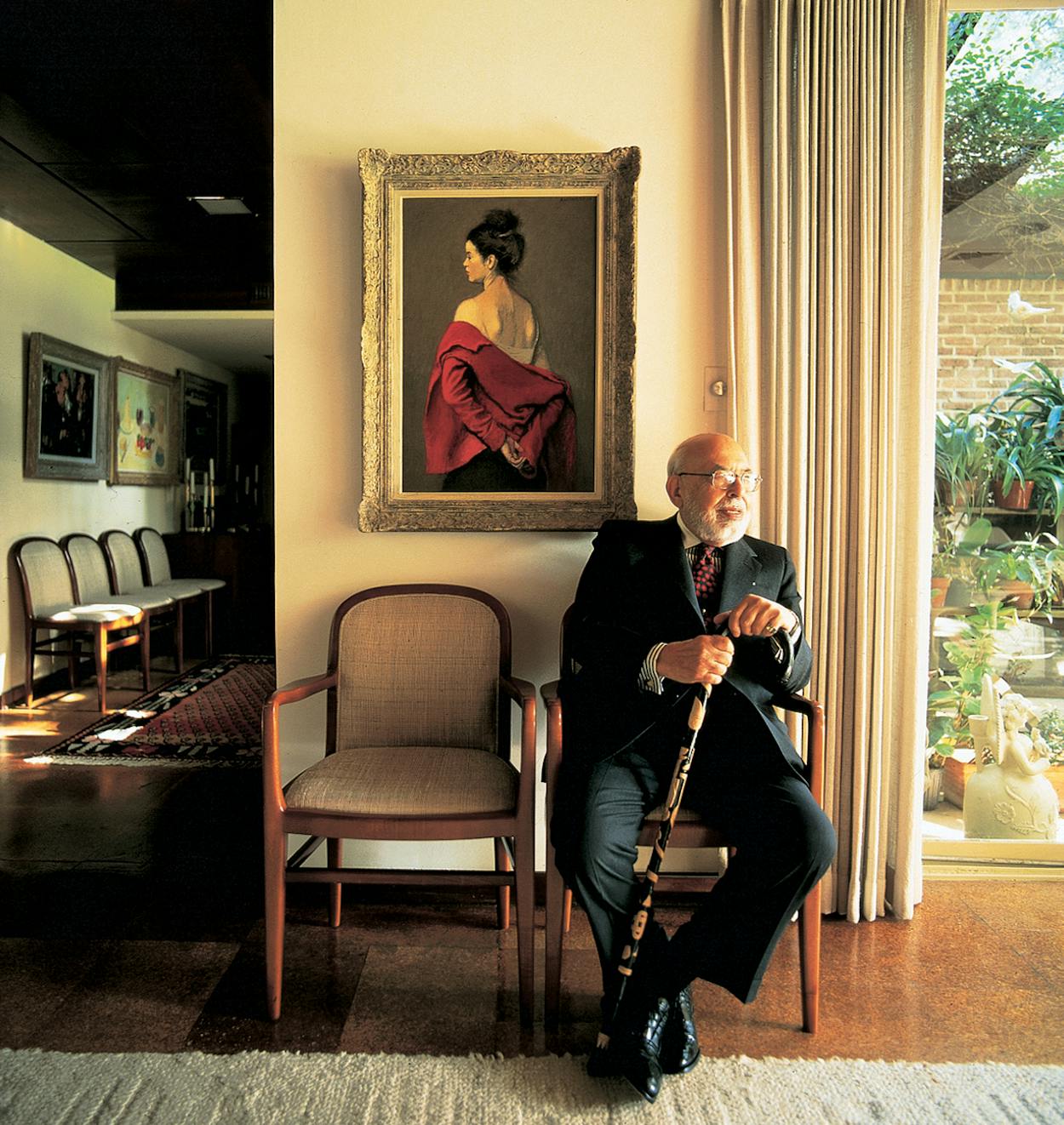

I thought of that dress the minute I heard, on January 22, that Stanley Marcus had died in Dallas at the age of 96. In his later years Marcus became something of a retailing Jeremiah, a white-haired, white-bearded sage forever kvetching about bad service to a public that didn’t care. Most people have embraced GapStyle; they don’t mind, as Marcus would have, that most of their clothes come in S, M, and L, and if they want Beluga caviar or espresso on Rome’s Via Condotti, as Marcus urged in his book Quest for the Best, they don’t connect these luxuries to any larger theme of gracious living, as he did. Nowadays it’s easy to confuse Marcus’ Harvard erudition with pretension (“I find myself in agreement with La Rochefoucauld, . . . ‘Good taste is the product of judgment rather than of intellect,'” he wrote); likewise, his assertion that one can learn to live well by reading W seems debatable. Even so, I understand why, at his death, the Texas canonizers were busy placing him on a par with Alamo martyrs.

At a time when Texas was so much more isolated than it is now—when Saks was just on Fifth Avenue and foreign food in Dallas was an enchilada—Marcus understood, brilliantly, how to make the Texas myth cut both ways. He grew up in a Dallas with world-class ambitions but, born a Jew, he also understood the outsider’s pain. Surrounded by newly rich who were terrified of getting it wrong, Marcus packed his store with the best of everything and offered up a social and stylistic insurance policy. This may sound silly, but so were the regional prejudices that kept Texans down for decades; I still wince when I read John Bainbridge’s 1961 account in The Super-Americans about the woman from Electra who, in 1927, walked into Neiman’s barefoot and wearing a sunbonnet, wanting a mink coat. After she paid cash for the coat, Bainbridge reported, Neiman’s also sold her a pair of shoes. The story managed to play both sides in favor of the middle: Yankees reveled in the stereotype while style-conscious Texans shopped the store so they’d never, ever be mistaken for oil-field trash.

But Marcus also appreciated what was good about us and knew how to exploit that for his own ends too. The playful lavishness of Neiman’s His and Her Christmas gifts (twin mummy cases, ermine bathrobes, Beechcrafts, and so on); the fact that he wore a sequined cowboy shirt while showing Coco Chanel around; and the clever, pointed name dropping (“While Princess Grace was visiting the Greenhouse prior to the opening of our show, I took Prince Rainier to the King Ranch, which fascinated him, as it does all visitors,” he wrote in Minding the Store) also proved to the world that we had something unique to offer: abandon, extravagance, fun. In his own elegant way, Marcus warned us not to throw the baby out with the bathwater, and so, of course, we didn’t.

He was, as his hagiographers suggest, the consummate retailer, but not because he could convince you that buying a dozen high-quality cotton socks was just as cool as buying one pair of cashmere. It was because he could keep two directly contradictory fantasies in play for decades without anyone’s actually noticing. We all bought in, which was just what he wanted.

- More About:

- Business