Compared with the glistening two-story mansions that surrounded it, the house looked like something from another time. It was only 2,180 square feet. Its redbrick exterior was crumbling, and its gutters were clogged with leaves. Faded, paint-chipped blinds sagged behind the front windows. Next to the concrete steps leading to the front door, a scraggly banana plant clung to life.

Built in 1950, it was one of the last of the original single-story homes on Northport Drive, in Dallas’s Preston Hollow neighborhood. The newer residents, almost all of them affluent baby boomers, had no idea who lived there. Over the years, they’d see an ambulance pull up to the front of the house, and they’d watch as paramedics carried out someone covered in a blanket. A few days later, they’d see the paramedics return to carry that person back inside. But they’d never learned who it was or what had happened. Some of the local kids were convinced that the house was haunted. They’d ride their bikes by the lot at dusk, daring one another to ring the doorbell or run across the unwatered lawn.

None of the neighbors knew that mailmen once delivered boxes of letters to the front door and that strangers left plates of food or envelopes stuffed with money. They didn’t know that high school kids, whenever they drove past the house, blew their horns, over and over. They didn’t know that a church youth group had stood on that front yard one afternoon, faced the house, and sung a hymn.

In fact, it wasn’t until the spring of last year that they learned that the little house used to be one of Dallas’s most famous residences, known throughout the city as the McClamrock house. It was the home of Ann McClamrock and her son John, the boy who could not move.

On the morning of October 17, 1973, John McClamrock bounded out of bed; threw on bell-bottom jeans and a loud, patterned shirt with an oversized collar; jumped into his red El Camino with a vinyl roof; and raced off to Hillcrest High School, only six blocks away. He was seventeen years old, and according to one girl who had dated him, he was “the all-American boy, just heartbreakingly beautiful.” He had china-blue eyes and wavy black hair that fell over his forehead, and when he smiled, dimples creased his cheeks. Sometimes, when he sacked groceries at the neighborhood Tom Thumb, Hillcrest girls would show up to buy watermelons so that he’d carry them out to their cars. On weekend nights, they’d head for Forest Lane, the cruising spot for Dallas teenagers, hoping to get a look at him in his El Camino—or better yet, catch a ride. One cute Hillcrest blonde, Sara Ohl, had been lucky enough to go out with John on her first-ever car date, to play miniature golf. After he took her home, she called all her friends and told them she had had trouble breathing the entire time they were together.

That morning, John sat restlessly through his classes. When the lunch period bell rang, he drove to the nearest Burger King to grab a Whopper. He pushed buttons on the radio until he found the Allman Brothers’ “Ramblin’ Man,” turned up the volume, and pressed down on the gas pedal to get back to school. He walked past the auditorium, where the drama club was rehearsing Neil Simon’s Plaza Suite; made a left turn; and then walked on toward the boys’ locker room to put on his football uniform. John—or “Clam,” as he was known among his friends—had a game that afternoon.

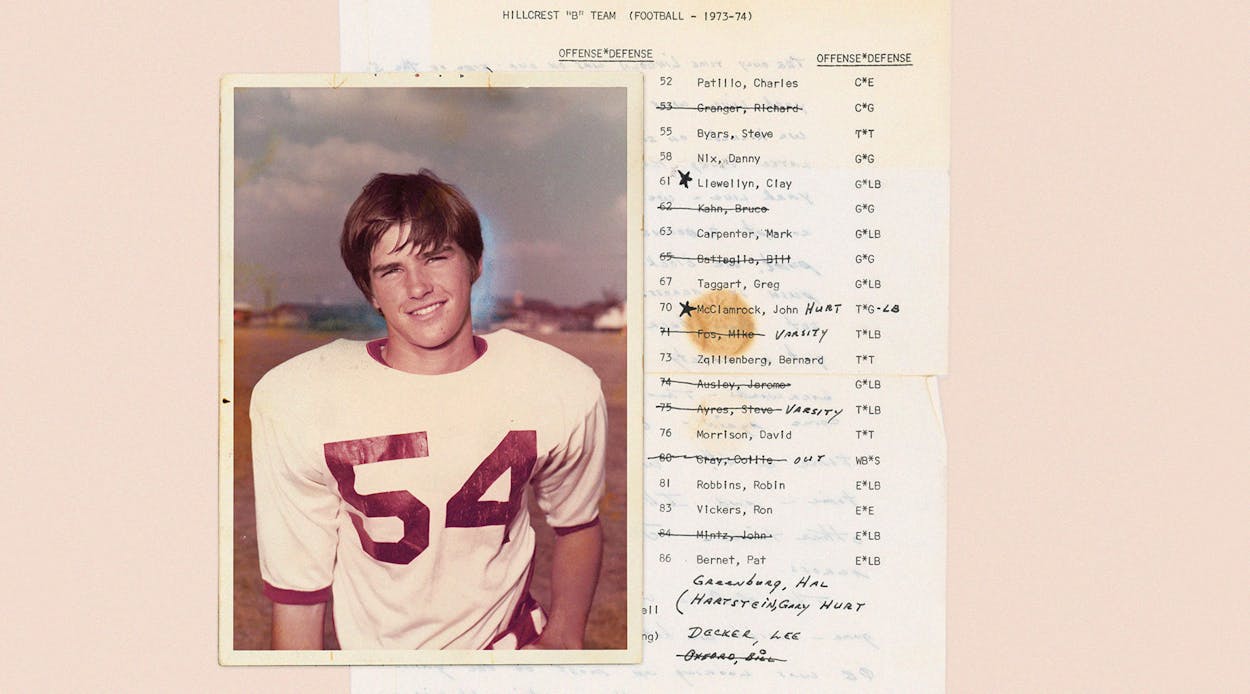

Earlier that summer, John had quit playing for the Hillcrest Panthers so he could work extra hours at Tom Thumb to pay off his El Camino. When he tried to rejoin the team at the start of his junior year, the coaches had ordered him to spend a few weeks on the JV squad. He was five feet eleven inches tall and weighed 160 pounds. He played tackle on offense, linebacker on defense, and he was the wedge buster on the kickoffs, assigned the task of breaking up the other team’s front line of blockers. That afternoon, the junior varsity was playing Spruce High School, and John was determined to show the coaches what he could do. This was the week, he vowed to his buddies, that he would be promoted to varsity.

On Hillcrest’s opening kickoff, he burst through the Spruce blockers and zeroed in on the ball carrier. He lowered his head, and as the two collided, John’s chin caught the runner’s thigh. The sound, one teammate later said, was like “a tree trunk breaking in half.”

John’s head snapped back, and he fell face-first to the ground. For the next several seconds, another teammate recalled, “there was nothing but a terrible silence.” Because there were no cell phones in that era, a coach had one of the players run to the high school’s main office to call an ambulance. When it arrived fifteen minutes later, John was still on the ground, his body strangely still. “You’ve got some pinched nerves,” a referee told him, speaking into the ear hole of his helmet. “You’ll be up in no time.”

But as soon as he was wheeled into Presbyterian Hospital, doctors knew he was in trouble. They gave him a complete neurological exam, scraping a pencil across the bottoms of his feet and taking X-rays, then ordered that his head be shaved and two small holes be bored into the top of his skull. Large tongs, like the ones used to carry blocks of ice, were attached to the holes, and seventy pounds of weight was hung from the tongs in an attempt to realign his spine.

A Hillcrest administrator called John’s mother at her office at a local bank. Ann McClamrock was 54 years old, a striking woman, green-eyed with strawberry-blond hair. She was, as her niece liked to say, “perpetually good-natured.” She always had extra food in the refrigerator for the neighborhood kids who came running in and out of the house, and on weekends she loved to throw boisterous dinner parties, most of them ending with her exhorting everyone around the table to sing corny old songs like “Skinnamarink.” When she arrived at the hospital, a doctor took her aside and quietly asked if she had any religious preference.

“I’m Catholic,” Ann said, giving him a bewildered look.

“Maybe you should call your priest, in case you need to deliver your son his last rites,” the doctor said. “We’re not sure he’s going to make it through the night.”

The doctor told Ann that John had severely damaged his spinal cord and was paralyzed from his neck down. He was able to swivel his head from side to side, but because his circulatory system had been disrupted, causing his blood pressure to fluctuate wildly, he could not lift his head without blacking out. “It couldn’t be any worse,” the doctor said.

At least outwardly, Ann seemed to take the diagnosis rather calmly. Or maybe, she later told her friends, she had simply been unable to comprehend the full meaning of what the doctor was saying. She stood at her son’s bedside until her husband, Mac, who had been out of town that day—he worked for a company that insured eighteen-wheelers—arrived with the McClamrocks’ other child, Henry, a quiet boy who was a freshman at Hillcrest. It was right then, with the family all together, that Ann felt the tears coming.

She slowly turned to the doctor, her hands trembling. “My Johnny is not going to die,” she said. “You wait and see. He is going to have a good life.” And then, her voice choking, she fell into Mac’s arms.

John made it through the night and then through the next day. His friends flocked to the hospital, many of them dropped off at the front door by their parents. One night, nearly one hundred kids were in the ICU waiting room, all of them signing their names on a makeshift guest register—a legal pad—pinned to a wall. There were so many phone calls coming into the hospital about John that extra operators were brought in to work the switchboard.

The local newspapers jumped on the story, and soon just about everyone in Dallas was following John’s struggle to stay alive. Dallas Cowboys coach Tom Landry and star defensive back Charlie Waters came to see him. The owner of the local Bonanza steakhouse chain held a Johnny McClamrock Day, donating 10 percent of all the restaurants’ sales to a medical fund. “Buy a Drink for Johnny” booths were set up at shopping malls all over the city, with proceeds from the $1 soft drinks going to the family. And at Hillcrest alone, there was a bake sale, a benefit basketball game, a bowl-a-thon, a fifties dance, and even a paper drive conducted by the Ecology Club.

Ann slowly turned to the doctor, her hands trembling. “My Johnny is not going to die,” she said. “You wait and see. He is going to have a good life.”

After one of the national wire services ran a story about John, letters began pouring in from all over the country. A group of North Carolina women who attended Sunday school together mailed John a card with an encouraging Bible verse. A faith healer from Michigan sent a note to let John know that “healing sensations” were coming his way (“You will begin to feel sensation . . . KNOW you are going to be UP and around very SOON”). John received hand-drawn get-well cards from Texas schoolchildren and sentimental notes from teenage girls who had never met him. (A girl named Patti wrote to let him know that she had played “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown” on her record player in his honor.) Then, in November, a letter arrived at the hospital from the most unlikely place of all: the White House. President Richard Nixon, who was in the midst of his spectacular downfall from the Watergate scandal—he was only ten days away from delivering his “I am not a crook” speech—had read about John and stopped what he was doing to write him a sympathetic note.

“Mrs. Nixon and I were deeply saddened to learn of the tragic accident which you suffered,” he began, “but we understand that you are a very brave young man and that your courage at this difficult time inspires all who know you. You have a devoted family and many friends cheering for you, and we are proud to join them in sending warm wishes to you always.”

In December doctors suggested that John be moved to the Texas Institute for Rehabilitation and Research, in Houston, which specialized in spinal injuries. Maybe someone down there could figure out a way to get him to move, they said. When he left Presbyterian, there were nearly four thousand names listed on the guest register. Students stood by the hospital’s exit and held up signs that read “Good Luck, Clam!”

While Ann lived in an apartment near the rehabilitation center and Mac and Henry visited on weekends, John stayed in a ward with other paralyzed men, going through two hours of physical therapy every day. The following March, when forty of his high school friends showed up to surprise him on his eighteenth birthday—they gave him the new albums by Elton John and Chicago—he was too weak to blow out the candles on his cake. But he assured them that the therapy was working. Speaking into a telephone receiver held by his mother, he told a Dallas Morning News reporter that he would walk again and “probably” would go back to playing football. “I will never give up,” he said in as firm a voice as he could muster.

But late that spring, doctors met with Ann, Mac, and Henry in a conference room. Staring at their notes, they said that not a single muscle below John’s neck had shown any response. He still couldn’t raise his head without losing consciousness, they added, which meant there was almost no chance he would be able to sit in a wheelchair.

One of the staffers took a breath. “We’ve found that ninety-five percent of the families that try to take care of someone in this condition cannot handle it,” she said. “The families break up.” She handed them a sheet of paper. “These are the names of institutions and nursing homes that will take good care of him.”

Ann nodded, stood up, and said, “We will be taking Johnny home, thank you.” A relative arrived with a station wagon, John was loaded into the back, and the McClamrocks returned to Northport Drive, where a newspaper photographer and some friends were waiting. Mac, Henry, and a couple of others carried John, who was wearing his Hillcrest football jersey, into the house. They twisted him into a sort of L shape as they turned down the hall and turned again into the guest bedroom, where they laid him on a hospital bed with a laminate headboard.

To make everything look as normal as possible, Ann redecorated the bedroom, hanging photos on the wall of John in his uniform. On a set of shelves she displayed footballs that had been autographed by members of various NFL teams, and she also placed the football from the Spruce game, which had been signed by his teammates. Because she had heard John tell his friends that he was determined to go hunting again, she had Mac buy a Remington 12-gauge shotgun, which she hung on another wall. Then she told her son, “Here we are. Here is where you are going to get better.”

Every morning before sunrise, she got out of bed, did her makeup and hair, put on a nice dress or pantsuit, dabbed perfume on her neck, and walked into John’s room. She shaved him, clipped his nails, brushed his teeth, gave him a sponge bath, shampooed his hair, and scratched his nose when it itched. She fed him all his meals, serving him one bite of food after another, and she taped a straw to the side of his glass so that he could drink on his own. She changed his catheter and emptied the drainage bag when it filled up with urine, and she dutifully cleaned his bottom as if he were a newborn whenever he had a bowel movement. To prevent bedsores, she turned him constantly throughout the day, rolling him onto one side and holding him in place with pillows, then rolling him onto his back, then rolling him to his other side—over and over and over.

From Monday through Saturday, she almost never left the house. On Sunday mornings, she went to Mass at Christ the King Catholic Church, lit a candle for John, and put a $10 check in the collection box. Afterward, she drove to Tom Thumb, the same one where John used to work, to buy groceries. Once a month she’d treat herself to a permanent at the hair salon at JCPenney. But that was it: Every other minute was devoted to John.

Perhaps Ann kept up such a schedule because she thought he didn’t have long to live. Within weeks after their return from Houston, he developed a kidney infection so severe it caused blood poisoning. An ambulance pulled up to the house. Paramedics ran inside, picked up John from his bed, and drove him to Presbyterian Hospital. Somehow he recovered, and when the paramedics brought him home, Ann kissed him on the forehead and said, “I’m so proud of you.” A few weeks later, he developed pneumonia, which forced another trip to the hospital. Once again, he made a comeback, and once again, as he was returned home, Ann went through her ritual, kissing his forehead and saying how proud she was.

For the next few months, his friends constantly dropped in to visit. Driving past the house on their way to and from school, they always honked their horns. When John’s friend Jeff Brown bought a classic 1939 Chevy Coupe, he drove it onto the McClamrocks’ front yard so John could see it from his window. And because the newspapers in those days printed the home addresses of people they wrote about, strangers did indeed show up with food and gifts. At least five well-wishers gave him copies of Joni, the autobiography of a young woman who was paralyzed at the age of seventeen but became a skillful artist, using only her mouth to guide her brush.

One Saturday night in May 1975, Ann left home for a few hours with Mac so that they could accept John’s diploma at Hillcrest High School’s graduation ceremony. When his name was announced and Ann began to walk across the stage, the cheers were so loud that people put their hands to their ears. The reporters wrote about his graduation; “Gridder Scores” was the Dallas Times Herald’s headline. When one journalist came to see him, John remained upbeat, saying he might take business law courses and someday try to pass the bar exam. “I really appreciate all the help everyone has given me and my family,” he said. “Tell everyone thanks.” But when the reporter asked him about his dream of walking again, he simply said, “Oh, I don’t know.”

Later that summer, before heading off to college, John’s friends came over to say their goodbyes. In September the sound of the crowds cheering at the Hillcrest football games on Friday night began drifting across the neighborhood. Although John’s window was always shut—his mother didn’t want pollen coming into the house because it might congest his already weak lungs—the sound slipped in anyway. John would listen to the band play the school fight song, and he knew exactly the place in the song where the cheerleaders would kick their long, beautiful legs. “Right there,” he’d softly say. “Right there.”

“Come on, Johnny, we can get through this,” Ann would say when she saw that look of despair cross his face. She would often read to him her favorite lines from a Catholic book of devotions she owned: “You can find the good in what seems to be the most horrible thing in the world. . . . God tells us that in all misfortunes we must seek the good. . . . Acting hopeless is easy. The real challenge is to hope.”

She would also show him a small, well-worn card, titled “Prayer of Thanksgiving,” which she kept on her bedside table. The prayer ended with the lines “Lord Jesus, may I always trust in your generous mercy and love. I want to honor and praise you, now and forever. Amen.” She told John that she read that prayer every night. “We must pray for God’s mercy,” she said. “That’s all we can do.”

But a lot of people who knew the McClamrocks could not help but wonder if God had abandoned them. In 1977, during Henry’s senior year at Hillcrest, doctors found cancerous lymph nodes in his neck. After removing them, the doctors told Ann and Mac that there was no guarantee the cancer was gone. A few months later, after paying his own visit to the doctor, Mac came home and told Ann that his nagging cough had been diagnosed as acute emphysema. Ann couldn’t believe what she was hearing. She had been married once before, right out of high school, and she had given birth to a son named Cliff, who was now grown. But her first husband had died of liver disease before she turned thirty, and now here was Mac—“the genuine love of my life,” she liked to say—telling her he too was going to die.

As Mac’s breathing worsened, oxygen tanks piled up in their bedroom. In January 1978 he walked down the hall to sit with John. Wheezing, he patted his son on the shoulder and said he was going to need to spend a little time in the hospital. He walked out of the house and died four days later.

The funeral was held on a frigid afternoon. Ann dressed John in a suit he hadn’t worn in five years and had him driven in a van to Christ the King Catholic Church. Other than his emergency trips to the hospital, it was the only time he had been out of the house. As he was pulled from the van and placed onto a stretcher outside the church, he exhaled heavily. “I can see my breath,” he said, his eyes widening. “I can see my breath.” He was pushed to the front of the sanctuary, next to the family’s front-row pew, and he turned his head so that he could watch a priest swing a burner of incense over his father’s casket. When John started to sob, Henry wiped the tears from his eyes with a tissue.

Incredibly, just two years later, Cliff called to say he had been diagnosed with lung cancer. He died in 1981, at the age of 39. At that funeral, people looked at Ann, convinced she was at the breaking point. Two husbands and one of her sons were dead. Another son was battling cancer. And, of course, there was John. Her niece, Frances Ann Giron, who always called her “Pretty Annie,” told her to take a vacation. “Go someplace you’ve always wanted to go, like New York City,” Frances Ann said. “I’ll take care of John. A long weekend. That’s all.”

But Ann shook her head. She drove home from the funeral, walked into John’s room, and put on her best smile for her son. “We’re going to keep fighting,” she said. “That’s all I ask—just keep fighting.”

They lived on Social Security disability benefits and a little insurance money. To help make ends meet, Ann, who had never gone back to her bank job after John’s injury, found part-time work with an answering service, taking after-hour phone calls for a Dallas heating and air-conditioning company that were forwarded to the McClamrock house. To save money, she ordered inexpensive clothes for herself from catalogs, and she continued to wear the same clip-on earrings she had bought when she first met Mac.

She and John developed a daily routine. In the mornings, either she read to him, mostly stories out of Reader’s Digest, or he read alone, using a page-turning device that he could operate with a nod of his head. They watched game shows and Guiding Light. They watched all the news broadcasts and movies on a VCR. Henry, who by then was living in his own apartment and working as a car salesman, would come over to sit with John on Sundays so that Ann could go to church and the grocery store. When she returned, she would fix a huge meal, usually chicken or pot roast with potatoes. Finally, at the end of each night, she would kiss John on the forehead and go off to her own bed, always reading her prayer of thanksgiving before falling asleep.

At least once a year, John came close to dying. He developed a urinary tract infection that nearly caused renal failure. Bladder stones clogged his catheter. His lungs filled with fluid, nearly drowning him. During his stays at the hospital, the doctors would say to Ann, “It’s touch and go.” But he always recovered, and as he was brought back into the house, Ann would always kiss him on the forehead and say, “I’m so proud of you.”

One afternoon, as paramedics carried him back into the home, he looked at his mom and Henry and said, “Here I am, still kicking.” He grinned and added, “Well, maybe not kicking.”

Ann was delighted. “That’s the spirit,” she said.

Although John had found it impossible to get through a college correspondence course because he couldn’t write anything down, he began watching all the history documentaries on PBS, he studied encyclopedia entries in hopes that someday he would be able to answer all the questions on Jeopardy, and he carefully read the newspaper (his mother folding the pages and putting them in front of him) so that he could have a better chance at guessing who would be the Person of the Week on ABC’s Friday-evening newscast.

Sometimes, he’d blow into a specially designed tube that allowed him to turn off the radio or television, and he’d stare at the ceiling, letting his mind wander. He kept a mental list of places he wanted to see: Alaska, the Swiss Alps, and the Colosseum, in Rome. He imagined himself taking a trip down the Nile or exploring Yellowstone National Park in the winter. And he spent hours thinking back on his life before his injury: the street baseball games he played with neighborhood kids in the fourth grade, the time he put twenty pieces of bubble gum in his mouth in junior high school, the students who passed by him in the halls, the Saturday nights cruising in his El Camino. He seemed to remember some days at Hillcrest in their entirety, right down to the food he ate in the cafeteria. “It’s like everyone else has all these new memories filling up their brains,” he told one of his closest friends, Mike Haines, a former lineman on the football team who had become a lawyer. “All I’ve got are the ones before October 1973.”

In March 1986, to nearly everyone’s surprise, he made it to his thirtieth birthday. Ann threw one of her old-fashioned dinner parties, inviting relatives and friends. At the end of the meal she made everyone sing “Skinnamarink.” Then she sang the ballad “How Many Arms Have Held You?” The dining room got strangely quiet. Everyone stared at Ann, this woman in her sixties who refused to be broken. At the end of the song, they turned to look at the motionless John, who was smiling at his mother, cheerfully telling her she still sang off-key. “You simply could not fathom how they were able to do it, day after day,” Ann’s niece, Frances Ann, later said. “I’d say to Pretty Annie, ‘Don’t you ever feel overwhelmed? Aren’t you ever bitter at what has happened to you?’ And she’d say, ‘Frances Ann, we can either act hopeless or we can make the best out of the life we have been given.’ And she’d show me that prayer of thanksgiving card and she’d say, ‘God will provide. I know he will.’ ”

Another year passed, and then another. Around the neighborhood, older residents began to sell off their little houses to a new generation of wealthy Dallasites, who would almost immediately tear them down to build mansions with high-ceilinged foyers and impressive “great rooms.” Ambitious young real estate agents would knock on the front door of the McClamrock home, and when Ann answered, they’d tell her that they could get her a large amount of money if she’d sell too. But she would quickly turn them away, their business cards still in their hands. “I’m sorry,” she’d say politely, “but this is our home.”

It was perfectly understandable that the new residents knew nothing about the McClamrocks. By then, John was no longer being written up in the newspapers: Reporters, predictably, had found other senseless tragedies to write about. In fact, by the time the nineties rolled around, a lot of people in Dallas who had once followed John’s struggles had forgotten all about him. Many of John’s classmates—the very ones who had flocked to the intensive-care waiting room so many years ago—had also lost touch with him. They’d certainly meant to visit, but one thing or another had gotten in the way, and now, after so many years, they were no longer sure how to restart the friendship they’d once had.

But in 1995, the organizers of the twentieth reunion festivities for Hillcrest’s class of ’75 put out the word that John, his mother, and Henry would be more than happy to entertain visitors. (Henry had moved back home after a divorce and undergone two more cancer surgeries on his already scarred neck.) During the reunion weekend, fifty or so classmates went by the house, and they were stunned at what they saw. Perhaps because he had not spent a day in the sun since 1973, John hardly seemed to have aged. His skin was perfectly smooth and his hair was still jet-black and long over the ears, exactly the way all the guys used to wear their hair in high school. And except for the shotgun—John had told Henry years earlier to take it down and give it to someone who could use it—nothing in his room had changed. The photos of John in his football uniform were still on the wall, and his clothes from high school, including his jersey, his bell-bottom jeans, and his loud, patterned shirts with oversized collars, were still in the closet. Even the same shag carpet covered the floor.

A couple women who had once dated him blinked back tears when they saw him. Another classmate, Sara Foxworth, a Dallas housewife and mother, gasped when she walked into his room and he called her name.

“But I thought you didn’t know who I was,” she exclaimed. “I was too shy to talk to you.”

“You sat three seats behind me in English,” he said. “And your locker was over by the cafeteria.” He gave her a gentle smile. “I remember,” he said.

Several of his old teammates, still muscular and narrow-waisted, had no idea what to say to him. They certainly didn’t want to make John feel worse about his plight by telling him about all the things they had done since high school. But John asked them about their careers, their wives and children, and where they went on vacations. He also assured them that he was doing just fine—that he even watched football on weekends and didn’t flinch when he saw a jarring tackle. “I’m the same person I’ve always been—only I don’t move,” he joked. And when each of his visitors told him goodbye, he said cheerfully, “Come on back, anytime you want. Believe me, I’m not going anywhere.”

Some of his classmates did come back around. A few of them brought along their children to meet John so they could learn about courage. (As soon as they got back to their homes, the kids would go lie in their beds, trying to see how long they could stay still.) Bill Allbright, a trainer on the junior varsity team who had become a successful financial adviser, found himself driving over to see the McClamrocks after he lost his wife to cancer, knowing they would understand his loss. And when Sara Foxworth was diagnosed with leukemia, she too showed up at the McClamrocks’. After she left, John asked his mother to come into his room with some stationery so that he could dictate a letter for Sara. He had his mom write the lines “You can find the good in what seems to be the most horrible thing in the world. Take good care of yourself. Sincerely, John McClamrock.”

Ann was then in her late seventies, and she was still maintaining her daily schedule, changing John’s catheter, cleaning his bottom, and turning him every couple hours, refusing any help. A few years earlier, after reading an article about exercise and a healthy heart, she had ordered a cheap stationary bicycle from a catalog, which she put in her bedroom and faithfully pedaled each night. Wearing ancient, cracked tennis shoes, she had also been taking quick walks around the block, pumping her arms back and forth.

But she knew that time was catching up with her. It wasn’t long after the twentieth reunion that she began adding a single sentence to the end of her prayer of thanksgiving. She asked God to let her live one day longer than John—only one day, she fervently prayed—so that she could always take care of him. “I’m not going to leave him,” she told Henry. “He’s hung on for me. I’m going to hang on for him.”

John did continue to hang on. He came down with another urinary tract infection. His intestines suddenly twisted, which forced doctors to push a tube down his throat and pump everything out of his stomach to provide him some relief. He got a bedsore so severe that plastic surgery was required to mend it. His lungs again filled up with fluid. But each time, he bounced back. As paramedics carried him inside the house, he would say, “Still kicking,” and his mother, following her ritual, would kiss him on the forehead and say, “I’m so proud of you.”

One afternoon, a pretty brunette named Jane Grunewald, who had been a classmate of John’s, called and asked if she could visit. Jane had married soon after graduating from Hillcrest and spent twenty years trying to be what she described as “the perfect PTA mom,” raising two children in the suburbs. But her marriage had fallen apart, and she was struggling. On that first visit, she and John talked for two hours. She began returning once a month, often wearing a lovely black dress, always bringing along Hershey’s Kisses for John. Before she arrived, John would have his mother wash his hair, comb his mustache, dab some cologne on his neck, and then pull his bedsheet up to his chin so she wouldn’t see his painfully thin body. Sometimes, Ann would fix them cocktails, carrying them into John’s room on a tray (with a straw always taped to the side of John’s glass). Then she’d leave them alone.

During one visit, Jane told him that he was the kind of man she longed for—someone who genuinely appreciated her. “And you’re always there for me,” she said.

“That’s true, you never have to worry about me running around on you,” John replied. He told Jane to look in the top dresser and pull out his old Saint Christopher pendant. “It’s yours,” he said. “I never did get the chance to give it to someone in high school.” She leaned down and kissed him on the cheek, leaving a thick red lipstick print.

He later told Henry that his monthly visits from Jane were his version of a love affair. “Not that we are going to have sex,” he said with a sort of resigned smile. “You know, I never had sex. I’ll never make love to a woman.” He gave his brother a look. “Is there any way you can tell me what it feels like?”

For Ann’s eighty-second birthday, on January 12, 2001, Henry brought home a gift, along with a takeout chicken-enchilada dinner from El Fenix and a bag of red licorice, her favorite candy. “To Mom, still kicking,” John said as she opened her present, a small bottle of perfume that Henry had bought at Dillard’s. Five years later, on her eighty-seventh birthday, Henry again brought home takeout enchiladas and a bag of red licorice, and John again said, “To Mom, still kicking.”

By then, it was obvious she was slowing down. Instead of getting dressed as soon as she got out of bed, she spent her mornings in her nightgown and her favorite green terrycloth bathrobe. She was having trouble hearing, and her eyesight was weakening. She began to wobble when she walked and once fell while cooking breakfast. A doctor told her that she had a type of vertigo and that she needed to stay off her feet. “Absolutely not,” she replied.

But in the fall of 2007, she fell again, breaking a bone in her right shoulder and tearing her left rotator cuff. It was the first time she had been admitted to the hospital since Henry’s birth, in 1959. Still, she left a couple days earlier than the doctors wanted so that she could get back to John. “I have to keep going,” she said when Henry came to take her home, and she suddenly burst into tears. “Henry, I can’t leave him.”

Only then did she allow Henry to take over the task of turning John in his bed. She let him make the instant coffee in the morning for the three of them. Because of her eyesight, she also agreed to let Henry drive her to Christ the King and the grocery store on Sundays. But she still had precise rules for their excursions. She told Henry that as soon as he dropped her off at the church, he had to immediately return to the house to sit with John. He then could pick her up at the end of the service and take her to the grocery store, but he had to drive right back to the house again to sit with John, and he could return to the store only when she called.

In January 2008, Ann, John, and Henry celebrated her eighty-ninth birthday with another takeout meal from El Fenix and another bag of licorice. A few weeks later, in the middle of the night, she thought she heard the sound of bedsprings squeaking in John’s room. She heard footsteps and then a hesitant cry.

“Mom . . . ”

She sat up, pulled her green terrycloth bathrobe over her gown, and headed down the hall. Because she could barely see in the darkness, she kept one hand on the wall to keep herself from falling. When she reached John’s bedroom doorway, she stepped forward and peered toward his bed, in the corner of the room.

“Johnny?” she asked. “Johnny?”

She was nearly out of breath. She turned on a lamp and there he was, 51 years old, lying on his back in his bed just as he had been for the past 34 years. He turned his head a few inches to the side and looked at her.

“Mom, are you okay?”

She took a breath and said, “I thought . . . ” And then she paused for a moment.

“I thought you had . . .” But she paused again, unable to bring herself to say the words.

It was the first time, she later said, that she had ever dreamed that John could walk again. “What does it mean?” she asked Henry. “What do you think it means?”

Not long after the dream, two new bedsores appeared on the backs of John’s knees. In late February, he was taken to Presbyterian. The doctors, realizing the tissue of his skin was wearing out and unable to withstand the constant pressure from the bed, suggested that he be admitted to a nearby rehabilitation facility, where a wound-care specialist could treat him.

Within days, he developed a fever, and because he could not cough with any strength, he was unable to expel any dust or mucus from his lungs. His weight dropped to 98 pounds. “You have to admit, my body held up for a long, long time,” he said when Henry dropped by to check on him.

“Come on now, you can get through this,” Henry said, using one of their mother’s phrases. “All you have to do is keep fighting.”

“Why don’t you bring Mom over?” John said. “Have her look pretty. She’d like for me to see her that way.”

“John, are you giving up?”

There was a long silence. A food cart rattled down the hall and a nurse’s sneakers squeaked on the hallway floors. From other rooms came the beeps of heart monitors and the deep whooshing sounds of ventilators.

“We know about her prayer,” John finally said. “We know she doesn’t want to go first.” He looked at Henry and said, “I need to go so she can go.”

On March 18, Henry drove Ann to JCPenney to get her hair done before he took her to the rehabilitation facility. Because she was so feeble, Henry put her in a wheelchair. He pushed her into John’s room, where she immediately began to check his catheter and inspect the bandages on his bedsores. “Mom, it’s okay,” John said.

She smoothed John’s hair along the temples. She touched his forehead, and she slowly ran her hand down one side of his face, past his cheekbones and the curls of his hair. She said, as if she knew what was about to happen, “Johnny, we’ll be back together soon.”

“I know we will,” John said.

Then he told his mother something he had never said before. “I know how hard it’s been for you.”

“Hard?” Ann asked. “Johnny, it’s been an honor.”

Henry took her home, helped her into her bed and made sure she had her prayer of thanksgiving card. After she fell asleep, he drove back to the rehabilitation facility to check on John one last time. A nurse greeted him at the door. John had died about thirty minutes earlier, she said. He had closed his eyes and quietly drifted away, not making a single sound.

It was standing room only for the funeral. Some of John’s childhood friends had flown in from around the country. Jane Grunewald, of course, arrived in one of her black dresses, and Sara Foxworth, less than a year away from death herself, was also there, gingerly taking a seat at the end of a pew. John’s schoolmate Jeff Whitman, a prominent Dallas eye surgeon, came straight from a hospital, still wearing his scrubs, and Dave Carter, the former Hillcrest swimming coach, who had named his dog after John, already had tears in his eyes when he walked into the sanctuary.

The mourners looked toward the front rows to get a glimpse of Ann. But just before the service began, a priest walked up to the pulpit to announce that she and Henry would not be there. Earlier that morning, the priest said, Ann had collapsed while getting dressed for the funeral and Henry had rushed her to Presbyterian Hospital.

The organist launched into the opening hymn, and John’s casket was rolled down the main aisle. He was dressed in the suit he’d worn to his father’s funeral. The priest waved a burner of incense over John’s casket and said, “May the Lord bless this man who is finally freed of the binds that have held him. May he run over fields of green.”

Ann returned home a couple of days later. Clearly disoriented, she wandered through the house, always holding onto a wall, not sure what to do. At one point, she picked up the phone and asked Henry for the number of a Dallas department store that had been closed for decades. She asked to talk to her father, who had been dead for fifty years. She then stood in the doorway of John’s bedroom, staring blankly at his bed. “Johnny?” she said. “Johnny, are you walking?”

Eight weeks after John’s death, Ann died in her bed, her prayer of thanksgiving card on the bedside table. Henry was sitting beside her, holding her hand. He had her cremated and her ashes put in an urn, which he decided to bury in the ground directly over John’s casket, at a cemetery near Love Field. At her service, the same priest who had presided over John’s funeral said, “We send off Ann today to be with the son she loved. We send her to the mansions of the saints.” The priest was about to say something else about Ann, but he saw Henry holding his hands to his face. “And may God bless Henry, who gave his life to his family,” the priest said. “God bless Henry.”

For days, Henry just sat in the little house on Northport Drive, not sure what to do. He finally got rid of John’s hospital bed and, except for his mother’s terrycloth robe, donated her clothes to charity. He then planted a For Sale sign in the front yard. Many of the neighborhood’s residents were no doubt relieved: The old house was finally going to be demolished so that a new mansion could be built.

But one afternoon, when he was in the front yard watering the banana plant, two young mothers on their power walk slowed down and waved at him. They said they had read a sports column in the newspaper eulogizing the McClamrocks. “We’re sorry we never got a chance to meet your mother and brother,” one of the women said, grabbing Henry’s hand. A few days later, a man got out of a luxury car, rang the doorbell, and told Henry he lived down the street. “If there’s anything we can do for you, let us know,” he said.

In March, a year after John’s death, Henry still hadn’t accepted any offers to sell. “I know I need to move on and get my life started again,” he recently told a visitor while the two of them sat in John’s room. “But I keep hearing Mom’s and John’s voices. In the mornings, I keep making three cups of instant coffee. When I go to the grocery store, I drive back home as fast as I can, thinking someone might need me.”

The visitor noticed that Henry had started remodeling, pulling out the old shag carpet and repainting the walls. Henry shrugged. “I don’t know if I can ever leave,” he said. “This has been a good home. It’s been a very good home.”

- More About:

- Sports

- Longreads

- High School Football

- Skip Hollandsworth

- Dallas