Only in East Texas could Nashville’s next big thing play second fiddle to a sweet potato. “These are the real stars around here,” says Kacey Musgraves, handing me a mama Golden sweet potato from a small wooden barrel. On this October weekend, Musgraves is in Golden for the thirtieth annual Sweet Potato Festival: two days of livestock shows, children’s pageants, and mutton bustin’ that lead up to the main event, a sweet potato auction. This year, there was live music too. And while Musgraves would never, ever say it, she’s slumming a little this weekend: playing a private party in conjunction with a sweet potato festival is an odd way to wrap a year that saw her share bills with Willie Nelson and Lady Antebellum.

Then again, to Musgraves, Golden—quietly nestled between Dallas and Tyler—is home. These days, she lives in Nashville, but she grew up here. Like the rest of the town, she freaked out a little when Oprah Winfrey held up a Golden sweet potato on her 2004 “Best of Everything” show, forever putting Golden on the map. This is where she played concerts as a 9-year-old, yodeling the oldies in fringy Western wear that would’ve made the 1.0 version of the Dixie Chicks proud. She’s 24 now, but not thirty feet from the barrel of sweet potatoes we’re admiring is the kind of stage she might have played way back when: a flatbed trailer decorated with Christmas lights and hay bales. This is where Musgraves will perform, marking her first time back to town since her debut single, “Merry Go ’Round,” started pushing into the top tier of the Billboard country charts. Musgraves’s mother booked this homecoming gig to celebrate the opening of her new art gallery. Saying no to Mom wasn’t an option.

“It’s very kitschy, but it’s also kind of great,” says Musgraves, who will play considerably larger stages in March, when she’ll open a series of shows for Kenny Chesney. “Coming home, you realize people are starved for live music. So it’d be lousy to come back and act like I’m tired of it. This is everything Nashville isn’t, in all the right ways.”

Exactly what Nashville is or isn’t has never seemed more up in the air than it does today. Is the town’s future full of glitzy vocal groups like the Band Perry or ballsy beer hustlers like Eric Church? At the 2012 Country Music Awards, Taylor Swift went home empty-handed, yet a few weeks later her new album—which leans more pop than country—notched the highest first-week U.S. sales figures of any album in a decade. Which is where Musgraves, who signed to Universal Nashville last year, might come in. Conventional wisdom on Music Row suggests there’s a generation of young female country fans who aren’t willing to transition with Swift to the pop realm. Right now Miranda Lambert, who grew up in Lindale, just twenty miles southeast of Golden, is the emblem of this movement, stacking six feet of authenticity and palpable danger into a five-foot-four-inch frame.

Early feedback from radio programmers indicates Musgraves’s “Merry Go ’Round” is laying the groundwork for a similar trajectory. “As poetic and potent as any song released in 2012,” said Rolling Stone. “An instant classic.” The poetic part hinges on the chorus’s stop-you-in-your-tracks triplet: “Mama’s hooked on Mary Kay / Brother’s hooked on Mary Jane / Daddy’s hooked on Mary, two doors down.” The potency comes from bleak assertions like “If you ain’t got two kids by twenty-one, you’re probably gonna die alone.” Don’t look for “Merry Go ’Round” to be the sound track to a Wood County tourism video anytime soon.

“My favorite kind of songs are clever without sounding like they’re supposed to be clever,” says Musgraves, who counts John Prine and Ray Wylie Hubbard as songwriting heroes. “Especially if they sound traditional but push the envelope a little in the message they’re conveying.”

Musgraves has been dissecting country songs for as long as she can remember. She was singing along with a karaoke machine while the other kids were playing Barbie, and then grade school talent shows gave way to weekends on the East Texas opry circuit. By twelve she was taking guitar lessons from legendary teacher John DeFoore—he taught Lambert as well as Michelle Shocked—who pushed her to focus on songwriting. “I think he knew I wasn’t the kind of student who was going to go home and shred on scales,” she says. “Instead, I wrote a new song every week and brought it back to him. Four years of that really helped me find my voice.”

After high school graduation, Musgraves moved to Austin and roomed with Lambert’s younger brother, Luke (the Lambert and Musgraves families have known each other for years). But she detoured to Nashville after she was tapped for the 2007 season of the USA Network talent show Nashville Star, where Lambert first gained national exposure. She sang just three times on air and came in seventh place but fell in love with the town and decided to move there for good.

Musgraves’s story could be a plotline on ABC’s prime-time drama Nashville (for which she co-wrote a song that was featured in two episodes): young woman from the sticks arrives in the big city, writes songs for big stars, and then steps out for her chance at the limelight. A few of the anecdotes Musgraves has to tell about what happened along the way are all but made-for-TV. Not long after hitting town, for instance, she took a gig playing children’s birthday parties. She’d dress as Cinderella or Ariel, sing a song, paint some faces, and earn $100. She told ’em to take this job and shove it when the talent agency asked her to dress as a French maid to deliver balloons to a birthday party at a fancy downtown steakhouse. “This sounded sketchy,” she says. “A week later I found out the gig was Blake Shelton’s birthday. Everybody I’d worked with, or would have hoped to work with one day, would have been there. I would have never lived it down.”

Her biggest songwriting credit to date is “Mama’s Broken Heart,” which Lambert recorded for her 2011 release, Four the Record. If Lambert’s name keeps popping up, perhaps it’s because country music is notorious for putting artists—especially female artists—in a box. You can understand why label execs who have had so much success with one take-no-guff East Texas gal would jump at the chance to promote another. But “Kacey Musgraves is the new Miranda Lambert” is too easy; an advance version of her debut album, due in the spring, suggests that while Musgraves can switch from sassy to gloomy on a dime, she pivots with a lighter, less sinister touch than Lambert. Better yet, you hear Tom Petty in her writing and Aimee Mann in her voice, neither of whom is an obvious Lambert influence.

“It hurts a little when you get thrown in the ‘angry Southern chick singer’ box,” Musgraves says. “I’m not angry. Really, I’m not.” Still, Universal has given her a surprising amount of creative control. She’s been working with her younger sister on album art and wrote or co-wrote every track slated for her debut. It couldn’t have hurt that she walked into the deal with a commitment from Luke Laird, Nashville’s hottest songwriter, to produce the album. A town where you can wear a nose ring and work with a guy who pens chart-toppers for Carrie Underwood is clearly going through some changes.

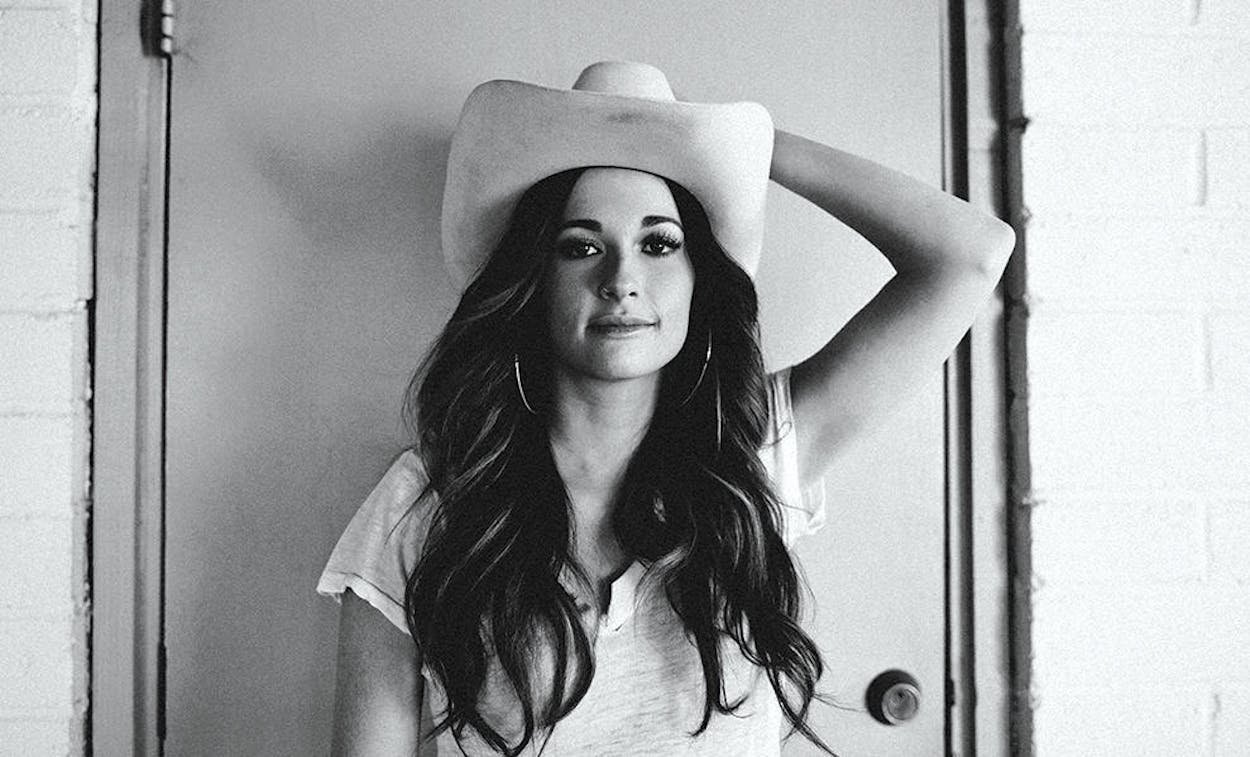

Yes, Musgraves sports a nose ring. And it hasn’t gone unnoticed in Nashville, which in many ways is still Nashville. Add a stray streak or three of dyed hair and you know why “unorthodox” and “outlaw” show up a lot in her press clippings. Musgraves thinks this is ridiculous and borderline chauvinist—and a sign that Nashville doesn’t know what’s going on in towns like Golden, where its demographic lives. “It’s crazy to me that there are people that see the nose ring and think it makes me a heathen,” she says. “I guess they think you have to look country to sing country music. Well, I spent a whole childhood looking like country music.”