Stephen Orlando never thought about being anything but a Houston police officer. A graduate of Waltrip High School on the city’s north side, he joined the force in 1975, when he was nineteen. His father is a police detective, his mother is a police dispatcher, both his older brothers are Houston cops. Like so many of his fellow officers, he drives a pickup truck and says his main hobbies are hunting and fishing. Also, like most of the other officers, he has experienced the frustrations of police work.

“You’re out there risking your life – for what?” he asks. Orlando feels hurt and resentful that most of the people he has encountered while in uniform don’t really respect him. Now 22, he still appears unformed, eager to please, obliging, the sort of guy you’d want on your softball team, someone you’d swap stories with over a beer. He seems, in fact, to be the sort of man who, given some leadership, would make a good cop.

Only Orlando isn’t a cop anymore. Last May he was fired from the force and then indicted – along with another Houston policeman – for the murder of Joe Campos Torres, Jr., a prisoner in their custody.

Torres’ death is just the most spectacular example of a recent deluge of violent police incidents. After the Torres killing, Mayor Fred Hofheinz, obviously anguished, said: “There is something loose in this city that is an illness.” Criminal lawyer Percy Foreman called Houston “a police state.” Today, he says, the Houston Police Department is worse, and its officers more violent and unchecked, than any comparable police force in the country. And Foreman is not a bleeding heart. He has defended scores of policemen charged with police brutality, and his own son is a Galveston lawman. Foreman lays the blame squarely on former District Attorney Frank Briscoe, who held office from 1961 to 1966, and his successor, incumbent DA Carol Vance. Both, he says, have “white-washed every charge against policemen,” thus encouraging even more police violence by letting police know that they are free from the sanctions of the law.

Vance, for his part, insists that he has always taken all the facts he has had about police misconduct to grand juries. He acknowledges, however, that most of the facts involving shootings by police or other charges of brutality usually are provided by the police department itself. Still, he, Briscoe, and other Houston leaders say that these incidents, while regrettable, are merely isolated blotches on an otherwise superior record. Briscoe says specifically that the two murder indictments in the Torres case “shoot the argument in the head” that police escape prosecution.

In the three and a half years since Hofheinz has been Houston’s mayor, more than 25 cases in which police have shot and killed or wounded citizens have gone without charges to Harris County grand juries. Only one officer has been indicted during that period: an off-duty policeman who wounded a businessman after their cars collided on a freeway. In the first six weeks after June 15, when the HPD officially opened an internal affairs division to investigate police misconduct, it received more than 180 citizen complaints.

The question remains: Are the Houston police out of control?

WILD IN THE STREETS

One incident involved a man armed with a Bible.

Milton Glover had the misfortune to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, and it cost him his life. A 27-year-old black warehouseman receiving Army disability pay for mental injuries suffered in Viet Nam, Glover was walking in the 7800 block of Hirsch Road in northeast Houston on the night of March 21, 1976, when officers in a patrol car spotted him and decided he looked “wild-eyed.” The police swerved across the road to confront him, blocking the path of a Volkswagen van driven by Allen Robinson. Robinson’s wife described what happened next: “He [Glover] put his left hand down and his right one up and the next thing was I saw him fall.” A stray bullet pierced the Robinsons’ windshield, spraying glass in her husband’s eye.

Another witness said, “The police officer got out of his car, Glover raised his right hand and said something to the officer, and the officer fired one shot. Glover fell to his knees and the officer continued firing.” The medical examiner’s report showed that police had pumped eight shots into Glover, seven from one gun. The officer who shot first, Richard L. Watson, is white, 25, and had been on the force two years. He said that when confronted, Glover began to pull something from his pocket that “in the dim lighting I believed to be a pistol.” It turned out to be a Bible.

The Glover case was routinely referred to a Harris County grand jury without charges. Only Watson, his partner Diane Miller, and the prisoner they had been hauling were called as witnesses, and the grand jury did not return any indictments. Subsequently, Glover’s family sued the city charging that officials responsible for the police department, specifically Mayor Fred Hofheinz and Police Chief Pappy Bond, had failed to see that policemen were “adequately trained and suited by temperament” for the job and had failed to deter “lawless behavior by employees of the Houston Police Department by means of prompt discipline and prosecution” of those who violate the law. This summer a federal grand jury began probing the Glover case for possible violations of his civil rights.

Sanford Radinsky was a wealthy lawyer in his middle thirties, although the source of that wealth, a family-owned finance company specializing in automobile loans, had seen better days. So, for that matter, had Radinsky: friends, including a number of able Houston lawyers, say that he was a regular user – but not a dealer – of illegal drugs, some of which had dissipated his health. His death in February of this year illustrates what can happen when police fail to distinguish between serious and trivial affronts to the peace and dignity of the community.

In late January, Radinsky, unnerved by a robbery of his Montrose-area home, moved to the Rice Hotel. After a tip from a hotel security officer about illicit activities in Radinsky’s room, a narcotics officer swore out a warrant saying a fellow officer had noticed “accidentally” through an open window on the twelfth floor that two women and a man were making love near some camera equipment. Police theorized that pornographic films were being made in the room (no evidence has surfaced to support this hypothesis) and placed it under surveillance. They sent undercover agents into the room on various pretenses; during these clandestine sorties the agents spotted pills they believed to be methaqualone, a depressant drug, the illegal possession of which is a misdemeanor.

That night a platoon of at least sixteen officers arrived at the Rice. They were not in uniform, but all were clad in bulletproof assault jackets. At about 1 a.m., search warrant in hand, they knocked on Radinsky’s door; one of them identified himself as “room service.” Inside, Radinsky was sleeping in the nude with two women; one of the women opened the door and the police burst into the suite. From this point, accounts differ. The cops say they shouted “Police!” The women say they didn’t. Radinsky was known to keep a gun in the room. Officer W.J. Stewart, who fired eight shots, seven of them hitting Radinsky, said Radinsky had pointed a gun at him. But one of the women told a television interviewer, “I saw Sanford stand up from the bed and I saw [officer Stewart] shoot him, and he fell to the floor and said, ‘Baby, I’m dead.’ And they just continued shooting. He had no gun, he had no chance to get one.”

Radinsky was suspected of a misdemeanor drug possession, yet his room was stormed by sixteen police officers in full battle dress. Three of the bullets found in Radinsky’s body had been fired from such close range that they caused what the medical examiner termed a charring effect, which occurs only when a gun discharges within fourteen inches of the victim. Stewart said in a written statement that Radinsky grabbed a pistol on the nightstand with his right hand – but Radinsky was left-handed. His gun was found across the room from his body with five rounds in it; the gun had not been fired. Apparently none of this concerned the grand jury very much; they no-billed Stewart after hearing testimony from the officers present but not from the two women.

The disturbing thing about the Radinsky case, and about most of the controversies in Houston over the use of police force, is the apparent presence of a take-no-prisoners mentality among law officers. One incident often cited by those who believe some Houston cops are kill-crazy is the shooting of Tommy Hanning, 39, a burglary suspect at a west Houston Firestone store, hardly a week after the Radinsky raid.

Twenty-five-year-old officer J. T. O’Brien answered a burglar alarm call at the tire store. With his partner covering the front door, he entered the store and encountered a man in the hall. O’Brien ordered him to lie on the floor, but he said the man began to run. O’Brien grabbed him, initiating a struggle during which he says the intruder stabbed him in the thigh with a pair of scissors. O’Brien fired repeatedly at the suspect – thirteen times in all; he explained later that because of the darkness he could not tell whether the bullets had hit their mark. Both a grand jury and a police investigation exonerated O’Brien.

On the basis of this information it could be argued that O’Brien had not acted out-of-bounds. He was defending himself against someone he had caught committing a serious crime. But two facts cast a shadow over the affair. In firing those thirteen shots, O’Brien paused to reload his pistol. And the medical examiner found that the shots all struck within a relatively tight pattern in the dead man’s torso.

AT ABOUT 2:30 on a damp, piercing morning early that same February a 24-year-old taxicab driver named Billy Junior Dolan was cruising southbound on Telephone Road without a fare. He glanced in his rearview mirror and quickly snapped alert. He saw a van pursued by a police car, its red and white lights blazing, closing on him fast. He cut his wheels sharply maneuvering his taxi in front of the fleeing van, thinking he could cut it off. When the van, unintimidated, almost ran into him, Dolan swerved again, this time out of its path. But for several miles he continued to stay beside it at speeds close to 80 miles an hour, hoping he could help block its escape.

Suddenly at Hall Road, not far from Clear Creek, the boundary between Harris and Brazoria counties, the van attempted to turn, stalled, skidded, and spun to a stop. A police cruiser slammed to a halt just short of the van, its headlights illuminating the bronze customized Dodge Deluxe “so I could see everything,” Dolan says. A second police car screeched to a stop behind the first. Almost instantly, Dolan says, a Houston policeman sprang from the first cruiser just as the young, long-haired driver of the van began to emerge from the vehicle with, according to Dolan, both hands in the air “so I could see space between his fingers.” The officer pulled the youth out and he and a second policeman threw him down on the pavement. The first officer, Dolan says, crouched with a knee on the youth’s chest; a few seconds later, Dolan heard “a kind of ‘puff’ sound, a muffled gunshot like when you shoot a watermelon, and I saw the kid twitch – he just killed that kid.”

Quickly, Dolan gunned his motor and sped south down Telephone Road, afraid, he says, of what the policemen might do to him. He told his dispatcher that “it was cold-blooded murder”; later that day he repeated his story for a homicide detective, who took his statement. “The police told me I lied about everything,” Dolan says, “but I know what I saw.”

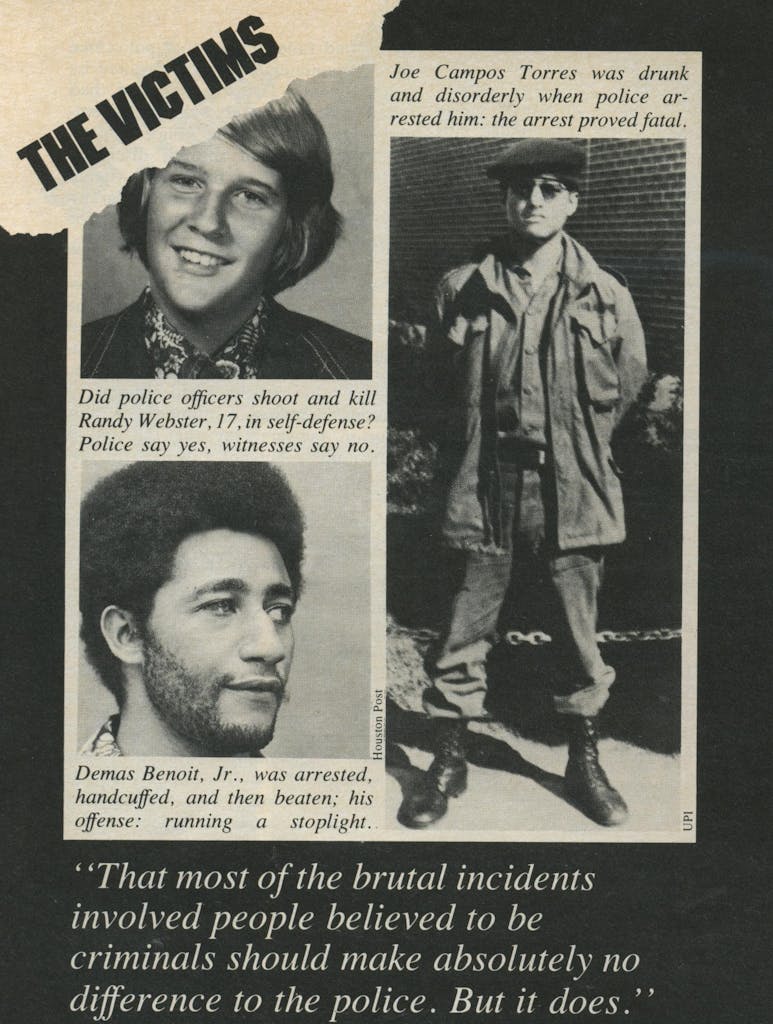

Randy Webster, the victim, was seventeen years old and had dropped out of high school in Shreveport during his senior year. He had had minor brushes with the law in Shreveport for things like stealing hubcaps, but had recently enlisted in the Navy. He had gone to Houston a few days before his induction.

Webster had stolen a van at Al Stokes Dodge on the Gulf Freeway, driven through a glass-and-aluminum bay door, and led police on a high-speed chase towards downtown, back under the freeway and outbound again, off onto the Reveille exit and through a police roadblock, and onto Telephone Road. According to the Houston Post account, the police version of the event was that officer D. H. Mays approached the van on foot as the driver emerged with a pistol in his hand. Mays fired once. Two other officers witnessed the shooting; one said the victim was in a standing position when the fatal shot was fired. Another press account quoted police as saying that four empty wrappers for the sedative Quaalude were found on Webster’s body.

During the frantic chase, in which the two lead police cars were nearly wrecked, Mays radioed the police dispatcher that he had sighted a rifle inside the van; it was never found and apparently didn’t exist. A witness near the end of the chase says that shots were being fired at the van. Although Houston Police Department policy doesn’t permit officers to shoot at fleeing vehicles, officers privately concede that it happens all the time.

The Webster shooting is another case where the police said the victim had a gun and a witness thought he didn’t. (One witness gave a corroborating account; another a conflicting one.) And once again, there are facts that fail to verify the police account and, in fact, cast heavy doubts on it. Despite the drug wrappers, the toxicology report revealed no drugs or alcohol in Webster’s blood. The autopsy report indicated that the fatal bullet entered the back of his head, and its path was downward. There was also a half-inch elliptical gunshot wound in the palm of his right hand, which is consistent, since only one shot was fired, with Webster raising his hand to his head in self-defense; this was the hand he supposedly pointed the gun at the police with. The gun found at the scene was unloaded. The only other thing known about it was that it had been shipped to Globe Discount Stores in Houston in 1964.

Webster’s father wrote Assistant Houston Police Chief B. K. Johnson that “my beliefs are that the gun and the [Quaalude] packages were planted on my son after his death.” He also requested that the three officers submit to a polygraph test; Johnson refused to ask them to do so. A grand jury heard testimony from the three police officers and from Dolan, then returned a no-bill; they later heard other witnesses but didn’t change their decision.

The two police witnesses who backed up Mays’ account of the Webster shooting had themselves previously been accused of using excessive force less than a month before. On January 15, according to a $100,000 damage suit filed by Robert and Alice Gleason, N. W. Holloway and his partner J. T. Olin were among several other cops who stormed into their Pasadena trailer home at about 5 a.m. The suit charges that Mrs. Gleason was dragged into the freezing cold barefoot and wearing only light pajamas. Her husband, the suit charges, was awakened when his bed was kicked by “a ring of armed men with beards, guns, and big lights,” who later ransacked their home, then forced him to open the office of his used car business, which they also searched.

None of the Houston police officers involved was disciplined, because the department determined there had been no violation of police policy; a “usually reliable source” had simply given them bad information that a man wanted on a murder charge was in the Gleason home, and the officers had a search warrant.

Only a fraction of the cases in which the police are accused of excessive use of force involve shootings. Far more common are allegations that police, administering summary “street justice,” beat prisoners in their custody. Such charges are rife not only in Houston, but also in virtually every other large city. Police know that because of overworked prosecutors, clogged court dockets, and apathetic judges, some small-time violators are not punished. There is a chilling maxim officers often demonstrate to suspects who brag that they’ll be back on the streets in no time: “You can beat the rap but you can’t beat the ride.”

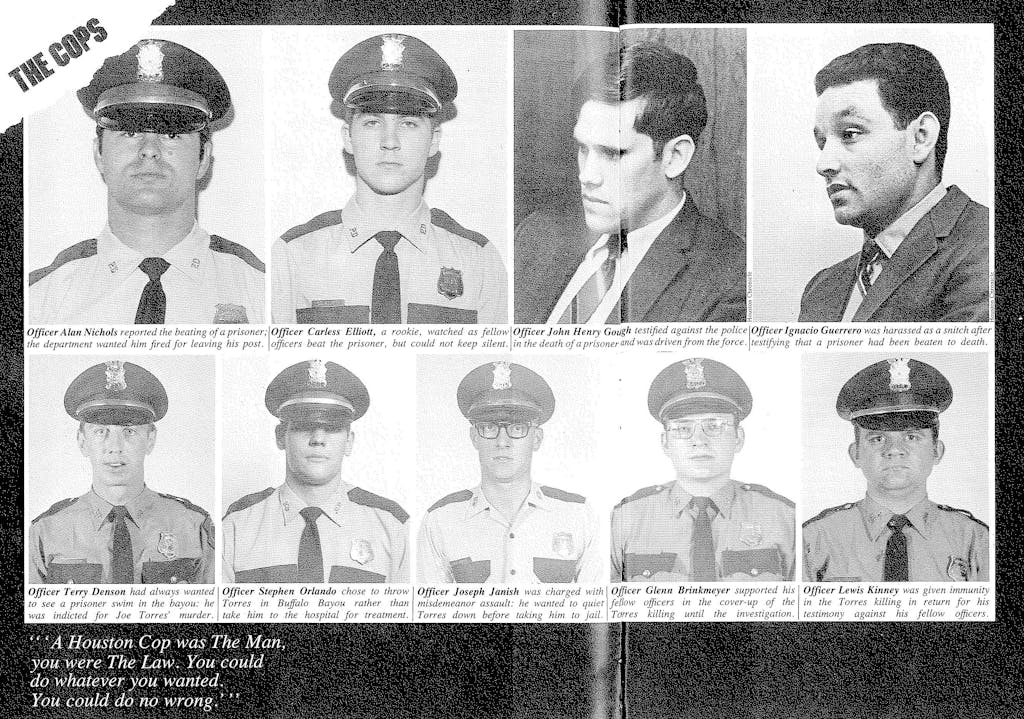

Two things were unusual about the early March beating of Demas Benoit, Jr., a black 21-year-old carpenter. There were witnesses willing to testify to the brutality (there seldom are) and one of the witnesses was himself a cop, a rookie two months out of the Police Academy. Benoit was arrested in front of his home on a Friday night after twenty police cars and a police helicopter had chased him at high speeds when he ran a stoplight on North Main. The rookie cop, Alan Nichols, said that after he had handcuffed the suspect, he noticed one officer holding Benoit by his Afro, banging his head into the ground, another kicking him in the neck and shoulders, and a third holding his foot on Benoit’s head. Nichols said he told the other officers, “Stop, that’s enough, I’ve got him handcuffed,” but they told him to shut up and let them do their police work.

Later, the officers explained – in what one source who followed the incident closely called a concocted story – that Benoit was biting one of the officers’ fingers, and the head banging was necessary to shake it loose. It is true, the observer says, that the officer’s finger was bitten – buy by a mental patient at Ben Taub Hospital the previous week.

When Nichols reported the affair, the internal police investigation cleared the officers and recommended that Nichols be fired on the grounds that he had left his post. However, Chief Pappy Bond merely reprimanded him.

TWO MONTHS AFTER the Benoit incident, another police beating came to widespread public attention. Again, the story rested on the testimony of just one officer – a rookie cop. Again a number of officers (five instead of three) had beaten a prisoner (Chicano instead of black) while his arms were handcuffed behind his back. However, there was one big difference this time: the victim died.

The dead man was Joe Campos Torres, a 23-year-old Army veteran and a laborer for a glass contractor. The following version of how his corpse was found floating in Buffalo Bayou last Mother’s Day is that of the Houston Police Department, based on an internal investigation ordered by Chief Pappy Bond.

Officer M. G. Oropeza had stopped a traffic offender in the 4900 block of Canal in the heart of Houston’s East End barrio on Thursday, May 5, when a boy ran up to him and said there was a fight in a club down the street. Oropeza radioed the police dispatcher to ask for another patrol unit to be sent to the bar, then headed there himself. It was just after 11:35 p.m. when he walked into the dark cantina. The manager had tried to eject Torres for quarreling with two other customers. There had been a scuffle, and the manager ultimately had pinned Torres on a pool table. Not mentioned in the police report was that Torres had a drinking problem that had resulted in his discharge from the Army the previous September, and on this evening he apparently was at the end of a twelve-hour drinking bender.

Soon after Oropeza arrived, two young officers from a patrol car also entered the bar. Torres began to fight with the three of them. Oropeza and officers Stephen Orlando and Carless Elliott wrestled him to the ground, handcuffed him, and dragged the cursing Chicano to the backseat of the patrol car. Soon two other patrol cars rolled up to the club, responding to the radio dispatch. Orlando told the four officers that the prisoner had given them trouble. One, Joseph Janish, a 22-year-old policeman with three years on the force, suggested that the officers attempt to quiet him. Oropeza returned to his patrol duties and the other three cars headed to a dusty warehouse district east of downtown, ending up near the 1200 block of Commerce. Here, two blocks of empty parking lots north of the Harris County Criminal Courts building, the three squad cars drove down an embankment to the south bank of Buffalo Bayou, far below street level. The officers removed Torres from the car, leaving him handcuffed, and all except Elliott, the rookie, struck him repeatedly. Before this episode came to an end, one of the officers, Terry Denson, remarked that he had always wanted to watch a prisoner swim in the bayou.

At this point, Orlando and Elliott returned Torres to the patrol car and took him to the city jail. The duty sergeant took one look at him and ordered the pair to take him to the emergency room at Ben Taub Hospital, where he could be treated prior to booking. Instead, Orlando decided to let Torres go, rather than spend several hours with him at the hospital, after which he would be able to charge Torres only with being drunk and disorderly.

But back in the police car, Torres again cursed the officers, and Orlando called Janish and Denson to suggest another meeting at the 1200 Commerce location. Officers Lewis Kinney and Glen Brinkmeyer, who had participated in the earlier beating, heard Orlando’s call and, uninvited, responded. Elliott removed Torres’ handcuffs, and Orlando told Denson that they needed to scare him before they let him go. Since Denson had wanted to throw somebody in the bayou, Orlando suggested this would be a good time. Denson took Torres by both arms, and all the officers except Elliott (who was responding to a dispatcher’s call) advanced toward the bank. “Let’s see if the wetback can swim,” Denson said, and he asked Torres if he could. Torres supposedly said he could, and Denson shoved him over the edge, a twenty-foot drop to the water. Elliott, returning from the police car, brought Torres’ wallet and handed it to Orlando, who pitched it into the water. The officers said they shined their lights on Torres briefly, saw him swimming across the bayou on his back, and departed. During the day on Sunday, three days later, his body was found. Subsequently, the medical examiner rules the cause of death was drowning.

After reporting for duty Sunday night, after Torres’ body had been found but before details of his death were known, Denson and Oropeza huddled with Orlando and Elliott and all agreed that if anyone questioned them, they would say that Torres had been taken to St. Joseph’s Hospital and released there. Just as in the Benoit case, however, the rookie cop found it hard to keep quiet. He told his father, who also happens to be a Houston policeman, and then related the story to Assistant Police Chief B. K. Johnson.

Pappy Bond knew this was no time for a coverup. This was more than a beating, this was murder. There was no possibility the policemen were acting in self-defense, and there was also a police witness. Bond filed a murder charge against Denson. Denson and Orlando were indicted for murder by a grand jury after three and a half weeks of investigation. Janish was indicted for misdemeanor assault, and Kinney and Brinkmeyer were given immunity from prosecution in return for their testimony. All five of these officers were fired by Bond. Elliott was returned to duty.

After the story came out, a senior assistant city attorney tried to put the best face possible on the Torres case. He told reporters it showed how the police department was able to clean its own house – a fact he called “the most significant aspect of the case.”

But it is possible to draw a different conclusion, which is: the events at 1200 Commerce Street would never have happened had not a long string of earlier incidents been tolerated and even ignored by official indifference, and had not excessive use of force been allowed to become a way of life for Houston policemen. The only reason that the truth came out in the Torres case is because the abuses by five police veterans could not be tolerated by a recruit so new that he had not adjusted to the ways of the brotherhood. He wasn’t yet a true Houston cop.

The Long Blue Line

Orlando and Denson, the two officers charged with murder in the Torres case, are typical examples of who become Houston policemen. From near Palestine in deep East Texas, Terry Denson is one of tens of thousands of semi-rural whites who have come to Houston during the past boom decade in search of work and opportunity. He worked nights on the docks of the Missouri Pacific truck lines, saving money to go to the University of Houston. In the middle of his first semester he was drafted and, instead of being inducted, joined the Marines. After a tour in Viet Nam, he returned to Houston and his old job at Missouri Pacific. When he was laid off, he decided to become a Houston police officer.

Twenty-seven-year-old Denson was a model cop with five years on the force when Joe Torres took his fatal plunge. Like Orlando, he had never fired his gun on duty, had in fact only drawn it once. In his file are five or six letters of gratitude from citizens praising him for his promptness, helpfulness, and courtesy. His last four performance ratings by his superiors classified his work as “outstanding,” the highest category. What didn’t show up in Denson’s file was the same sort of growing frustration Orlando felt, that the police were fighting a losing battle. Denso believed public resentment was building up against the badge itself. People he stopped in traffic were increasingly belligerent; witnesses to crimes wouldn’t come forward; people just didn’t want to be involved with the police. Meanwhile, Denson saw the courts letting up on criminals. People arrested for routine municipal court offenses – possession of four ounces or less of marijuana, misdemeanor theft, and vice charges – hardly seemed to stay in jail at all. “They’d be out the front door before I’d complete the paperwork,” Denson says, or they’d be dismissed on some technicality or get probation. “You’d just throw up your hands and say, ‘What the heck? What good does it do to catch them?’”

Justice seems more on the side of the criminal; the public doesn’t want to help; nothing we do matters. Those are constant laments from Houston policemen. Society has changed so much in the past ten or fifteen years that being a policeman is undoubtedly an increasingly frustrating job. And frustrations are not what many Houston policemen are equipped or trained to handle. Although the department rejects nineteen of twenty applicants, those who do become policemen are drawn, according to recently appointed Police Chief Harry Caldwell, from the bottom quarter in economic status and education. In contrast to Dallas where 38 per cent of the officers are college graduates, and Austin, where 22 per cent are, only 11 per cent of the Houston force hold college degrees.

The department’s selectivity also works to eliminate applicants who might be experienced in dealing with the variety of people who make up an urban society. The prospective cop may not live with a member of the opposite sex without being married, must never have committed adultery, may not use marijuana, and until recently had to be over five feet, six inches in height. Applicants are tested on such matters with a lie detector. Many people who have been to college in the past ten years would likely fail the marijuana test, more than half of all women would have failed the height test, and a number of applicants would fail the adultery and cohabitation tests. It is not at all clear that such people make “bad” police. In fact, a recent independent study of the department’s selection criteria and promotion procedures maintained that marijuana use and cohabitation were not valid reasons to reject applicants.

Even with these requirements, the force has more than tripled in size in the last twenty years, from 800 to more than 2800 members. Only 151 are black, 166 Mexican American, and 146 women. The remaining 85 per cent are white males. Even though beginning officers now earn more than $1000 a month, this has apparently failed to attract minority applicants. Lieutenant I. L. Stewart, assistant director of recruit training, believes the department is unsuccessful in drawing qualified minority applicants because of the heavy competition for such people from private industry. That may well be part of the reason. Another part may be that the ethnic homogeneity of the department is self-perpetuating. “It’s been ‘us’ versus ‘them’ for years,” says Houston minister William Lawson. “Blacks have been mistreated by the Houston police department for so long that they can’t imagine becoming part of it.”

Martin Reiser, a psychologist for the Lost Angeles Police Department and an expert on the stress of police work, thinks that during the first three or four years of work – the approximate tenure of most of the Houston officers charged with shooting and brutality – recruits go through what he calls the “John Wayne syndrome.” Idealistic, flexible, open-minded recruits are transformed into cynical, overserious, emotionally withdrawn, strongly authoritarian officers. Accompanying this syndrome, says Reiser, is “the development of tunnel vision…in which there are only good guys and bad guys, and situations and values become dichotomized into all or nothing.” The chief factor promoting this malady, he says, is peer pressure – which he calls “one of the most profound pressures operating in police organizations.”

The cops who have blown the whistle on police brutality in Houston are cut from essentially the same mold as their fellow officers. The difference between them and the others is that they were all rookies. They had yet to lose their idealism and adopt the strongest rule governing policemen: No officer shall snitch on another officer no matter what he does.

To become a cop is to become initiated into an embattle brotherhood; to betray one brother is the ultimate sin, since it is to betray the brotherhood itself. The only time an officer will break that code – will, as they say, “let his milk down” – and testify against another officer, is if he has been wrongfully accused and can be exonerated only by the truth. Preserving the brotherhood is the end of the code, and it is an end that justifies virtually any means.

Those rookies who broke the code felt the full weight of the brotherhood. Back in 1970 two twenty-year-old rookies named John Henry Gough and Ignacio Guerrero testified in state and federal courts that they had witnessed two other Houston police officers beating a suspect to death in the Galena Park police station. Both men were harassed as snitches. Under the pressure, Gough left the force and became a truck driver. Guerrero weathered the storm and is now assigned to the jail division. Officer Nichols, who witnessed the Benoit beating, was also ostracized. He received obscene and threatening phone calls, telling him that “snitches die” and suggesting that his wife might be harmed. Although police investigators recommended that Nichols be fired, Chief Bond did not do so (Nichols was likely saved by Mayor Hofheinz’ public defense). Bond said, however, that Nichols “became overly emotional and reacted inappropriately” and that he promised to counsel him to realize his potential as a police officer.

This code is not unique to the Houston Police Department, of course. It functions to different degrees, and to protect different practices, in police departments across the nation, not to mention in corporations, in professions like medicine and law, in the armed forces, and in penitentiaries. In Houston the code has functioned primarily to cover up a pervasive pattern of police assaults on citizens. Interns in Ben Taub Hospital’s emergency room have a firsthand, nightly view of the brutality. “These things happen just about every night,” said one senior medical student working in the hospital’s suture unit. “It’s hard to imagine how someone would get a three-inch gash in his scalp, a quarter-inch deep and bleeding profusely, unless he was hit with a nightstick or a six-cell flashlight. But the policemen usually say, ‘Oh, he fell down,’ if I ask what happened, or ‘He hit his head on the patrol car as he was going in the door.’”

It is no doubt a fair assumption that since police do not normally deal with the finest and most upstanding citizens, some of these battered people in custody may well have resisted arrest, or had a “bad attitude,” or otherwise offended an officer. Most incidents never reach the newspaper. If Torres had simply swum away after being beaten up and tossed in the bayou, nothing would have ever been heard about him.

If there is one attitude that permeates the Houston police force, it is this feeling of being unappreciated and isolated from the world. “Our next-door neighbors are friendly to our faces, but maybe they ostracize us behind our backs,” says retired Sergeant E. R. Williams. “As a result, we normally associate with other police officers. Criticism of the police just aggravates the situation, and removes us more and more from the rest of society.” And their opinion of the rest of society often is not very high. “There are almost more bad ones than good ones out there,” says officer W. R. Morris, who is 24 and has been with the HPD for five years. “I was tired of seeing innocent people being dumped on, so I became a policeman. I wanted to put the turds in jail, but they all get away these days. The courts are for the turds, the law is for the turds.” Like many Houston cops, he identifies these frustrations with the city itself and doesn’t live there. Morris lives in Spring. His partner, J. L. McGee, lives in Conroe. “Well, we work here,” McGee chuckles, “that’s bad enough.”

A great deal of the isolation the police feel, however, stems from a very reasonable cause: fear. Police work, like war, can be described as 99 per cent utter boredom and 1 per cent sheer terror. The knowledge that the 1 per cent could come anytime, anywhere, does not make for relaxed, smiling cops. Police violence is only part of the widespread violence in Houston, and the cops feel it can turn on them at any time. “Every citizen is potentially a threat to me,” says Lieutenant I. L. Stewart. “There are a lot of criminals out there. You don’t know who they are, but they know who you are.” Officer Morris, who has never fired his gun on duty, understands why some officers do, and how easy it would be to make a mistake and shoot an innocent person: “It isn’t that you’re gun happy. It’s that you’re scared shitless.” The cops see themselves as targets and they feel that anybody – the driver of the next car they stop, an ordinary pedestrian, an angry spouse in a domestic quarrel – anybody could be the one to take a shot at them. This is understandable, and some officers readily call themselves paranoid.

That fear became a reality for officer James Kilty in April 1976. Kilty was shot and killed while trying to apprehend a heroin dealer. He was the only Houston cop killed on duty last year. But Kilty wasn’t just any cop, he was a supercop. Back in 1971, when many children of the white middle class were becoming as apprehensive about the cops as blacks had always been, Kilty organized the Pigs versus Freaks softball game in the Houston bohemian neighborhood of Montrose. The Pigs won, of course, but the game briefly brought the two tribes together. Soon after the game, Kilty became an undercover narcotics officer, the most dangerous and corrupting of all police jobs. A veteran police beat reporter remembers that Kilty, however, “got the dope, he got the crooks, but they never turned him around. Kilty was what all cops ought to be.”

Narcotics officer Richard V. Sander responded to Kilty’s death by organizing a course to drive home to cops just how endangered they are. It uses dramatic live reenactments, firing blanks, of the actual killing of police officers. Writing about the course in Police Chief magazine, Sander noted: “The degree of shock apparent in the students’ expressions indicates the impact of the demonstration…The class is stunned. They stand in utter silence. Some take cautious steps backward in a brief moment of disbelief. At least one, out of reflex, reached for the weapon in his belt that was not there, while he watched the ‘blood’ run down the face of a downed officer.” The training also includes a raid on a residence, where “violators” armed with blank weapons await the students, and a simulated “felony vehicle stop.” Sander notes that the importance of that exercise “is obvious when the majority of the role-laying officers are dramatically ‘killed’ while the rest of the class watches in stunned surprise.”

Certainly such training is as important to becoming a good police officer as simulated combat is to becoming a good soldier. But the training the police receive in when, as opposed to how, to use deadly force is woefully inadequate. The Texas Penal Code and the Houston Police Department manual add up to this: an officer can shoot someone if he feels that person is an imminent threat to his own life or someone else’s, but he may not do so in circumstances in which a reasonable person would have retreated. However, the manual emphasizes, “there is no duty to retreat before using deadly force” if the incident occurs during an arrest and there is a “serious risk” of death or serious bodily harm at the hands of the person being sought if the arrest is delayed. Obviously these fine distinctions are not always easy to analyze in the heat and fear of the moment. But the decision to shoot to kill is the most fundamental decision a free society places in the hands of its police. Therefore it should logically be the focus of a good deal of training exercises at the Houston Police Academy. But of the 640 hours of instruction a police cadet receives, only two deal with the proper use of deadly force. That is roughly equivalent to the training Army Lieutenant William Calley received on the Geneva Convention and the rules of war. When police are rigorously trained with dramatic simulations on how to use weapons – but receive only a perfunctory lecture on when – it is not surprising that they will, but training and design, use their weapons more than they need to.

Everything about police work in Houston, from the backgrounds of the police themselves to their training to the violence of the city, contributes to the current situation, where violence against citizens is increasing and where the police are feeling more and more isolated from the society they are supposed to serve. Other cities have dealt with similar problems, however, and most cities have managed to train and mold their police forces into disciplined units. Why hasn’t that happened in Houston? Young officer Nichols inadvertently gave one answer when he talked about his ostracism after the Benoit beating. “The feeling that whatever a police officer does is all right because he’s a police officer scares me,” he said. “It sounds like something Germany would have had during World War II. I can’t believe it’s here in Houston, Texas. You can’t change this attitude from the bottom up – you have to change it from the top down.”

The Buck Stops Where?

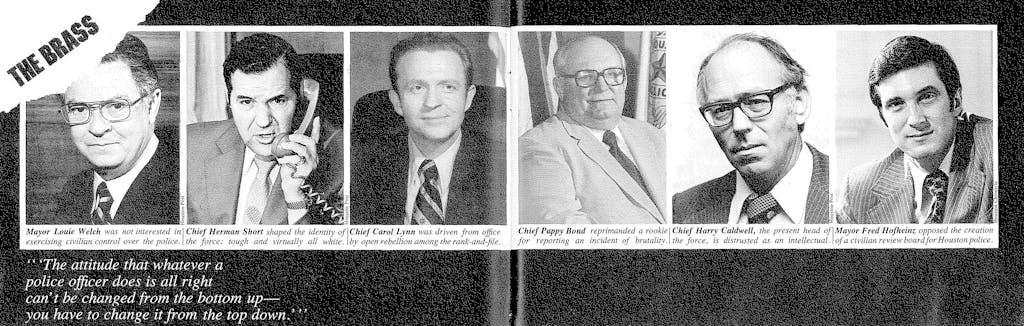

In Houston the top means the mayor, who has stronger inherent power (legal, if not political) than the head of any other big city in the nation, including Chicago. But during his five terms in office (1965-74), Louie Welch interfered as little as possible in the affairs of the department. He left matters in the hands of Police Chief Herman Short, a man who more than anyone shaped the character of the Houston police force.

Short, a broad-shouldered, brusque, perpetually frowning man, was the image of a tough police chief. He was also, said presidential candidate George Wallace, someone who would be a good choice for FBI director. Under Short’s reign, which even admirers called dictatorial, Houston was the biggest city in the U.S. that refused all federal funds for its police department. Short didn’t want to be hampered by federal regulations – especially any that might force him to hire more black officers. Short’s police force was taut, tough, and virtually all white, and mirrored his often stated but exaggerated opinion that blacks represented the city’s chief crime problem. Under Short, Houston also had the nation’s largest police department without an internal affairs division to investigate its own officers for wrongdoing — a situation that ended only this summer.

One former policeman from the Short era recalled the prevalent attitude on the force in those days: “If you were a Houston cop, you were it. It wasn’t that way in Dallas or San Antonio or anywhere else. A Houston cop was The Man, you were The Law. You could do whatever you wanted. If you were a Houston cop, you could do no wrong.”

In some eyes, perhaps; in others, Short’s minions could do little right. Short’s reign paralleled a decade of social unrest and ferment: it was the age of black protest, student activism, and widespread use of drugs, and Short displayed little understanding of what was going on in his city. Typically, the police were unable to distinguish between political and criminal events: police spies took notes and pictures at events ranging from protest at a garbage dump to meetings of the Harris County Democrats, the party’s liberal wing. The forty-member Criminal Investigation Division busied itself by spying and maintaining files on such threats to the public weal as Barbara Jordan, then a state senator, and conservative Congressman Bob Casey. Mayor Fred Hofheinz subsequently announced that police maintained more than 1000 such files, including one on him. For the last six years of Short’s term, four divisions in his department embarked on a massive and virtually unsupervised program of illegal wiretapping, using devices constructed by police communications men on the sixth floor of police headquarters. Short’s successor Carol Lynn said that anyone who had spent much time in public life had probably been wiretapped. And the whole period was punctuated by repeated claims of police brutality, mostly from blacks.

The controversy over Short and his police raged so openly that the bitter mayoral elections of 1971 and 1973 were, more than anything else, referenda on whether Herman Short would continue to rule the Houston Police Department. The issue first boiled over in 1970 after a black youth died following an alleged police beating in the Galena Park police station. In the wake of that incident, incumbent Mayor Louie Welch issued an edict that police would have to stop referring (as they did routinely) to blacks as niggers over police radios. Welch survived a 1971 runoff against Hofheinz but stepped down in 1973. Hofheinz was elected that year by a narrow 3000-vote margin, largely on the strength of better than 95 per cent majorities in black boxes. The results were clearly a mandate to do something about the police department, and in any event, Short had let it be known that he would not serve under Hofheinz.

For practical reasons (among them that under state law the city council must confirm the appointment of a new chief, and Houston’s would not accept an outsider), Hofheinz was forced to look inside Short’s department for a new chief. But when he looked at the deputy and assistant chief levels, he generally found their occupants too old, too sick, too fond of the bottle, or too corrupt (one was under investigation by the IRS for tax fraud and was later sentenced to three years in prison; another was suspected of involvement with a stolen car ring). Others, his advisers judged, simply would have sabotaged the new mayor’s efforts at reform.

So Hofheinz reached below the assistant chief level to choose a captain at the Police Academy, Carol Lynn. It was a poor choice. Lynn, a nervous, improbable man for the job, was in trouble almost from the start. He had no command experience and never got support from his troops to carry out his reforms. Lynn also lacked one other important practical requirement as chief: he didn’t have twenty years of service. That meant he could not retire with a pension after his tenure as chief. “It was kind of like telling a commanding general that he can only be a general for awhile, and then he will have to go back to being a colonel and one of the colonels he has chewed out will be the general,” says a former Hofheinz insider who was in on the decision to pick Lynn. “He would have to go back to being one of the boys if Hofheinz lost the next election. It was untenable for him.”

To the ordinary cop, Lynn seemed to be working against the department’s interest: the probes into wiretapping and spying were anathema to most of the force. Lynn’s top aides undercut his reforms, blocked his investigations, and generally seized every opportunity to cut him up. Then a Houston grand jury looked into charges that he had fixed parking tickets; it did not indict Lynn, but the damage was done. Nineteen months after he was appointed, Lynn resigned in the face of an overwhelming rank-and-file rebellion orchestrated by the Houston Police Officers Association and just as Hofheinz faced election challenges from two law-and-order candidates who said Lynn would be a major issue. That experience, says Dick DeGuerin, head of the Harris County Trail Lawyers Association and a strong critic of police violence, “gave them all the encouragement they needed to believe that the mayor was weak-kneed and wouldn’t do anything about them. Now the cops run the chief, instead of the other way around.”

After Lynn, Hofheinz again reached below the assistant chief level to select Captain B. G. (Pappy) Bond, a porcine, humorous officer with shrewd instincts who had earned a reputation in the department as a skilled bureaucratic politician. During Bond’s tenure (he resigned last spring to run for mayor, then changed his mind and accepted a job as security chief of Tenneco), Hofheinz occasionally tried to restrain the police. He spoke out, for example, in support of officer Nichols and may have influenced Bond not to follow the investigating committee’s recommendation that the rookie be fired. After Radinsky’s death, Hofheinz said that officers needed better training in when to use their weapons, a position Bond first contradicted, then supported. But at 61 Reisner Street, police construed Hofheinz’ remarks to mean that cops needed better training in how to use their firearms, which wasn’t true, they joked, because “we’re hitting everything we’re shooting at.”

Many of Hofheinz’ critics – not his political enemies but his disappointed friends – say that while his sentiment was admirable, sentiment is not policy. They blame the mayor for failing to take action; one frequently cited incident involves a bill introduced during the legislative session this year by State Representative Craig Washington, a talented criminal lawyer and an outspoken critic of police treatment of blacks. Washington wanted to create a civilian review board for Houston, but Hofheinz strongly opposed it: “We already have civillian review,” he said with circular logic. “We elect the mayor.” Without support from city hall, the controversial bill had no chance; most of the Harris County delegation shunned any association with it.

Hofheinz concedes that he leaves office with the police department “still not supervised by civilian control as it ought to be” and that there is “a pattern of cover-up and police excess.” But he insists that he has made improvements since the Short era. Relations with minorities are better (they could hardly have deteriorated), there are more women, black, and Chicano officers, and the spying has ended. But to work more fundamental changes, to reshape the hostile attitude of the cop toward the city he polices, is quite another matter. Part of the problem, Hofheinz says, is an optional state civil service law that voters in Houston (unlike those in Dallas) have adopted; it “makes every cop a king” and makes it “extremely difficult to discipline a police officer unless he’s caught red-handed.”

Ironically, part of Hofheinz’ problem may have been one of the “reforms” he most often cites: more than one-third of the 2800-member force, 946 officers, has been recruited since January 1974.

“One of the worst things that can happen to a police department is for it to grow too fast,” says Hofheinz’ predecessor Louie Welch. He should know: during the last four years of his term, the force grew by 736 officers. The rookie officers, Welch says, are almost inevitably the ones put on the street at night, when most of the crime occurs. Often they are put there without the restraining supervision of a seasoned officer, most of whom have been pressed for years by their wives to get off the night detail, Welch continues. As a result, many rookies never get the crucial in-service training of working with a veteran police officer, even though police, like members of most other professions, learn the largest part of their job outside the classroom.

All this was beginning to become obvious late in Welch’s administration, when a growing number of brutality complaints led him to remove investigations of serious complaints from the police department and turn over that responsibility to the city legal department. This was done “out of necessity,” says Welch, because the police department couldn’t be trusted not to cover up to protect its own officers.

Most of the time, though, Welch has nothing but kind words for the force: he calls it “an unusually good department,” says recent developments are “bad on its morale,” and concludes that claims of brutality “come in waves and many of them have absolutely no foundation – these are just things that every cheap criminal and their defense lawyer jump on.” The former mayor’s attitude reflects what Hofheinz says is the crux of the police problem: the dominant attitude of the city’s business leadership (including Welch, who is now president of the local Chamber of Commerce) that the police should be supported even when they are wrong, and that in any situation where the facts are in dispute, the police should be believed without question. Criminal attorney Percy Foreman attributes the widespread business community support for the police to studied indifference. He says, “There is so much money to be made here that people in leadership don’t have time to think about anything but that.” Sometimes business attitudes hearken back to sixties-era confrontation politics – and us versus them mentality. For example, one executive of a major Houston corporation maintains that police display no excessive brutality – a view that implicitly accepts, and even encourages, a certain amount of brutality to preserve the status quo and keep them in their place.

Among those who have looked kindly on the police is the judiciary, or at least the judges who have transferred police brutality cases out of Harris County to friendlier climates. The 1970 beating death case in the Galena Park police station was tried in New Braunfels, a German-American hamlet and retired military stronghold likely to view the police side of the story with great favor. (“I knew we had the case won,” the police defendants’ lawyer, Racehorse Haynes, has said, “when we seated the last bigot on the jury.”) Similarly, the Torres case will be tried in Huntsville – where the main industry is the Texas Department of Corrections.

Influential members of Houston’s large and powerful law firms also take a charitable view toward the police. Gibson Gayle, immediate past president of the State Bar of Texas and a partner at Fulbright & Jaworski, is “pretty well pleased as a resident of this community with the job that they do.” A. Frank Smith, managing partner of Vinson & Elkins, rates the department as “good” and says the instances of brutality are isolated. Hugh Patterson, a politically potent senior partner at Baker & Botts, says “I don’t think members of the Houston Police Department are any more prone to violence than the ordinary citizen in this part of the country, and I think they are racially tolerant.”

One of the strongest supporters of the police in the business community is N. W. (Dick) Freeman, retired board chairman of Tenneco, who says bluntly, “I think the police department should be congratulated rather than condemned.” Another strong and important backer of the police, and the leading political Tory in town, is Everett Collier, editor of the Houston Chronicle. Collier believes that the police “stick together, but not to the degree that they would hide a violation of the law.”

The simple fact is that there is little realization among the leading citizens of Houston that when you give a man a uniform and a gun without leadership and without the training to handle it, you may have a dangerous situation on your hands. Nothing can be done until this lack of awareness (or indifference) is erased. What to do then is another question: perhaps a police-citizen review board would help, perhaps more training in self-restraint, perhaps a special prosecutor to look into past and future cases of police misconduct instead of the current system that uses assistant DAs and grand juries who get most of their evidence from the police themselves. But clearly community attitudes must be changed before police attitudes can be.

The police do a necessary and sometimes dangerous job, and many do it well. They must face danger, endure abuse, and abide the frustration of sometimes seeing those they capture go free. But it is a job they choose freely, and in many ways it is a very good one. Few men can have as much responsibility and discretion as a police officer who is essentially his own commander in the field.

When police anywhere, as a number in Houston have, come to respond to their frustrations by dishing out their own retribution – verbal harassment, beatings, and worse – respect for the crucial job they do plummets and their own isolation from the community increases. It is true that most Houston officers are good men and women who do not engage in such behavior. But it is a truth that is negated because the best officers almost without exception cover up for the actions of the worst. As a result, those charged with enforcing the law become participants in what is really systematic lawlessness.

Police brutality isn’t limited to Houston, of course. But the sheer volume of incidents, the apparent shoot-first-and-ask-questions-later mentality, and the almost total absence of civilian control does appear unique among American cities. On the other hand, as Houston officers stress, there has been relatively little evidence of widespread corruption of the kind that seems endemic among the police rank-and-file in cities such as Chicago and New York. Still, who is to say that if police in Houston are free to break one law, they won’t break others?

That most of the incidents of brutality involved people actually involved in crimes or believed to be criminals should make absolutely no difference to the police. But it does. As the head of the Houston Police Officers Association, Detective R. C. Rich, says about the Torres incident, “I’m not saying what happened to him was right, but he was out there violating the law and his own people called in on him. If he hadn’t been out there drunk and raising hell, nobody would have messed with him.”