I moved to Amarillo from Holdenville, Oklahoma, in 1944, when I was sixteen years old. It was a tough move. I had just found the most beautiful girl in Holdenville, and I didn’t want to leave. But everything came together pretty quickly for me in Texas, and attending Amarillo High became one of the great experiences of my life. I still remember going to an assembly at school and thinking there were more people there than in the entire town I had come from. And as it turns out, I found another beautiful girl, Mary Jo Phillips, who was a neat gal and became my girlfriend.

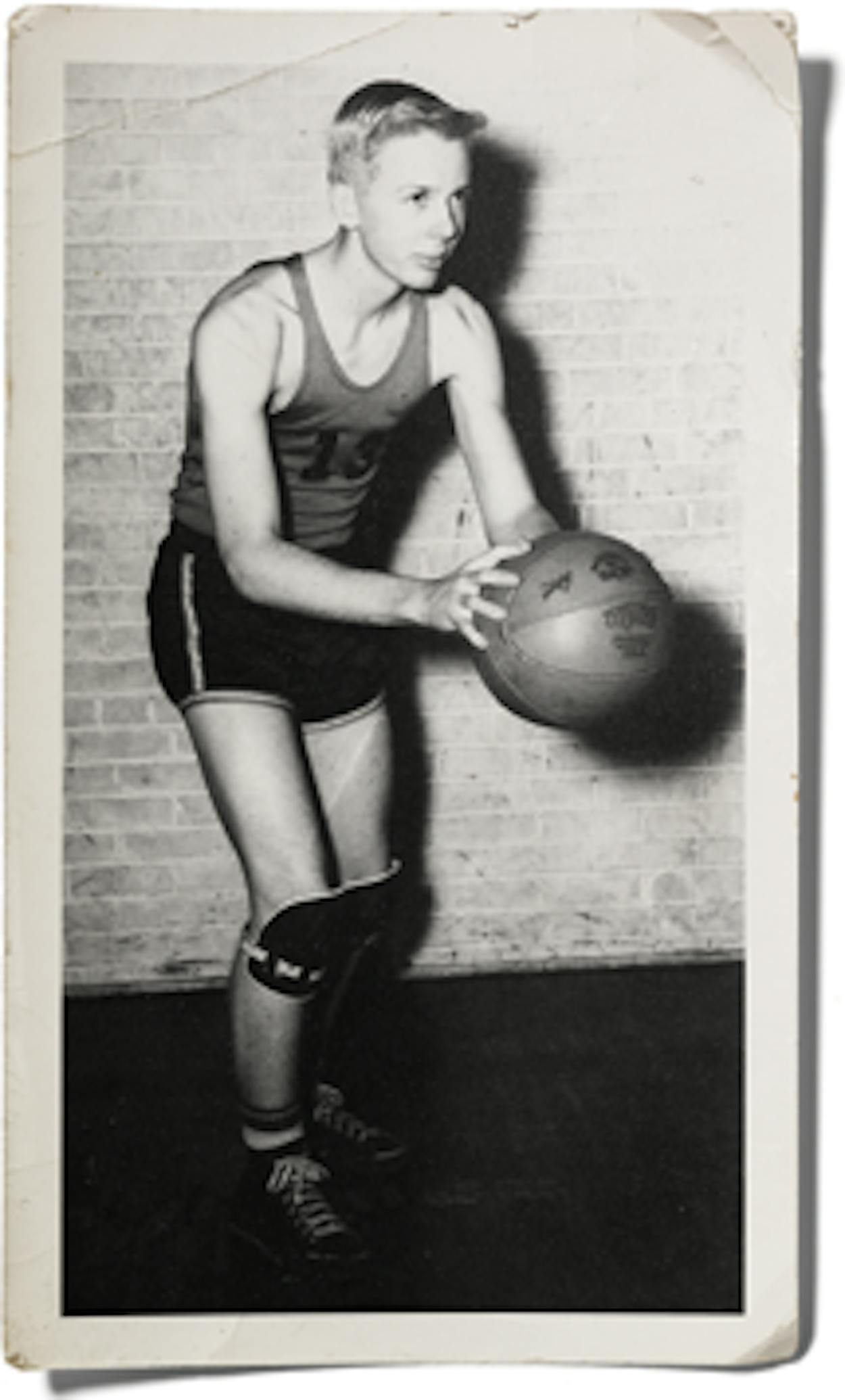

I loved to play basketball, and I was a pretty good guard. When I was in the eighth grade, I was the manager of the Holdenville team that won the state title, and I was hoping that by the time I got to play varsity, we’d be state champions again. So the most disappointing thing that happened to me when I arrived in Amarillo was that I couldn’t play basketball right away. Back then, Texas had a rule that if you had played outside the state, you were ineligible your first year. I came in as a junior, so I sat out that first season. I joined a city league before I was able to play for the Sandies and T. G. Hull. He was a great coach, and he taught us that when a game was over, it was over. You never dwell on a loss.

During my senior year, we made it as far as the state semifinals in the tournament in Austin. We played against Thomas Jefferson High School from San Antonio, but they beat us 37—36. I scored eight points. I guarded Kyle Rote [who later played football for SMU and the New York Giants], and he guarded me. I still think we should have won that game. I kept in touch with many of the players over the years. Jimmy Carter died first; he was a pit boss in Reno. Bob Henry died too; he was a school superintendent in New Mexico. Jewell McDowell, the best player on the team, died ten years ago. And Larry Wartes died last year. I’m the last one alive.

I was a rich kid in Amarillo, not because I inherited it but because I always had a job. During the holidays and the off-season, I had part-time jobs. I worked for Freeman’s Flowers, for example, where I handled deliveries. Over the summer I worked for the railroad and belonged to the union: I was a boilermaker’s helper, and then I was a signal maintainer’s helper. I was also a switch engine fireman for two summers. I’d make enough money to hold me over for all my dating through the school year. I always figured that if I started with $300, I could make it. Friday nights were pretty typical. We would go to a movie and then eat at a hamburger joint called the Double Dip drive-in on Polk Street.

I could have graduated in 1946, but I wanted to play for the Sandies one more season. Polk Robinson had offered me a scholarship to play at Texas Tech, but I didn’t take it. In fact, Mary Jo graduated in 1946, and she ended up working in the athletic department for Coach Robinson. Her leaving caused a big split for us. Around Christmas, I walked out of class at Amarillo High, and she was waiting for me. She told me she wanted to talk, so we went over and sat in her father’s car by the old armory, where our team practiced. She told me that Coach Robinson would still offer me a scholarship if I enrolled at the start of the spring semester. I told her that we were in the middle of the season and that it wouldn’t be fair to the team if I left. And then she asked, “Well, would it be fair to me?” So I looked at her and didn’t know what to say, and right then I heard a thump, thump, thump on the window. It was Coach Hull, and he growled at me, “Time to go to work, Boone.” So Mary Jo said, “Okay, that’s it. Which way are you going to go?” And I said kind of sheepishly, “Well, Coach Hull says I need to get to practice.” And that was that.

Later that day Coach Hull came over to me and said, “Boone, quit fooling around with her. I know her parents, and she’s a lot like her mother. She is going to be running your life.” And looking back on it, that probably would have turned out to be true.