Save for the occasional stains left by waters that rose roughly three feet high, the outside of the brick ranch-style homes along Lucian Lane looked mostly untouched. The grim evidence of Hurricane Harvey’s unprecedented flooding was instead marked by piles of debris lining the streets: crumbling Sheetrock, warped dressers, soggy mattresses, faded photos in shattered frames, an elliptical trainer that looked like a mangled grasshopper. Members of Team Rubicon, an emergency response outfit run by military veterans, had already scoured this neighborhood in Friendswood, a middle-class suburb southeast of Houston, gutting the houses and hauling the storm’s detritus to the curb. But there was one residence where the curb remained empty, and the pile of debris was stacked a few yards away, all of it neatly staged for a photo op.

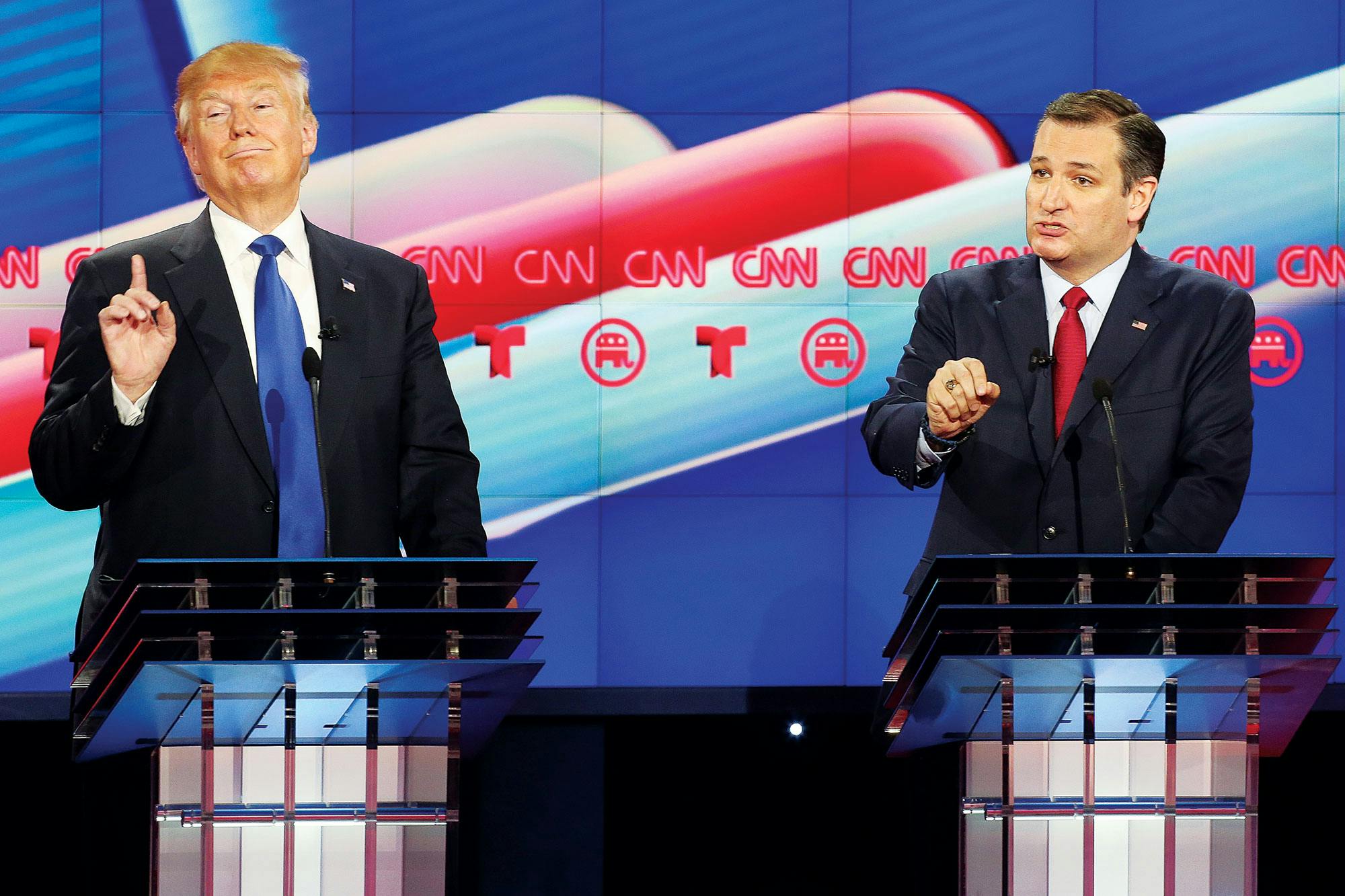

Across the street, a scrum of media jostled for position beneath a blue pop-up canopy erected to shield their cameras from a sporadic mist. Shortly after 11:00 a.m., a caravan of black SUVs arrived, and U.S. House Speaker Paul Ryan and Texas senators John Cornyn and Ted Cruz stepped out together. Earlier that morning they had toured the Harris County wreckage by helicopter. Now, along with other members of Texas’s congressional delegation, they donned Team Rubicon T-shirts and prepared to work.

Some of the congressmen looked primped for the photo op—one wore a polo shirt and docksider shoes—and some appeared actually ready to sweat, most notably Cruz, who sported brown steel-toed boots and a camouflage cap with a Texas flag patch on the front. It took them exactly thirteen minutes to transfer the debris to the curb, even with some shuffling like elderly men on a chain gang. Then Cruz, Cornyn, and Ryan moved to a microphone set up directly in front of the cameras.

It had been nearly a month since Harvey had made landfall, but media speculation about Cruz’s response still swirled. Five years earlier, after Hurricane Sandy flooded New York and maimed much of the Atlantic coast, Cruz, a freshman at the time, became one of 36 Republican senators—including Cornyn—to vote against the federal relief package. Yet the vote stuck to Cruz more than any other, partly because he had begun to earn a reputation as the most reviled member of the Senate but also because he took the opportunity to accuse “cynical politicians in Washington” of using the relief package as a “Christmas tree” for unrelated spending. (An original Senate version did in fact include unrelated spending, but it was stripped out in the House. When the bill returned to the Senate, most of the money was tailored to Sandy relief.)

So when Cruz joined Cornyn in the days after Harvey to seek federal funding for the Texas coast, many were swift to accuse him of hypocrisy. Representative Peter King, of New York, tweeted that he wouldn’t “abandon Texas” the way Cruz had New York. Cruz’s former Republican presidential rival, New Jersey governor Chris Christie, told reporters it was “disgusting” for Cruz to use Harvey victims “as a backdrop” while “he’s still repeating the same reprehensible lies about what happened with Sandy.” Cruz retorted that he was “quite confident that nobody in Texas gives a flip what Chris Christie has to say.”

On this day, when Cruz stepped to the microphone, he called the initial $15 billion appropriation merely a “down payment.” And while Ryan was reserved when discussing further aid, Cruz, in characteristically bold terms, promised “substantially more.” Cruz clearly recognized that Harvey presented a real opportunity with Texas voters—after five embattled years in the Senate, his approval ratings had declined, and his Senate reelection was on the horizon—but his approach to Harvey relief also signaled that perhaps he was no longer the obstreperous senator who’d earned such notoriety during Sandy.

After his failed presidential bid, rumors had floated up from the Senate that Cruz was going to become more conciliatory. In January 2017, Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell, whom Cruz once called a liar, introduced him at a Republican luncheon as “the new Ted Cruz.” National publications began anointing him “Ted Cruz 2.0,” as if he were an android in need of a firmware upgrade. The New York Times said he was “kinder, gentler.” By year’s end, even former U.S. House speaker John Boehner, who once called Cruz “Lucifer in the flesh,” told Politico he was proud of Cruz for acting responsibly in 2017—even if he was still “the most miserable son of a bitch I’ve ever had to work with.” Alas, Cruz couldn’t escape the Friendswood press conference without managing one dig at his colleagues: “We all collectively have just witnessed a miracle, which is members of Congress doing actual work.”

As the photo op wrapped, most of the congressmen headed back to their vehicles to leave. Cruz wasn’t finished, though.

“There are no Democrats. There are no Republicans,” Cruz said to the crowds, sounding a lot like a previous president he’d repeatedly vilified.

His aides whisked him a few miles south to a tiny yellow house in Alvin, where the owner still lived in a tent in his front yard surrounded by a stand of palms and banana trees. Team Rubicon members had already begun ripping up flooring and marking Sheetrock for removal. There were no news cameras this time—I was the only journalist, and I wouldn’t agree to make the volunteer work off the record. Cruz demonstrated experience with a pry bar and hammer as he scored and busted the flooded drywall. He worked with determination, without small talk, focused on the task at hand. He told me he had volunteered at about six homes since the storm, mostly through his home church, Houston’s First Baptist.

About 45 minutes in, as everyone gathered for a water break next to a ruby-red pickup truck filled with trash bags and supplies, a chatty Team Rubicon member from Norway stepped in front of Cruz and began arguing that Hurricane Harvey was proof of global warming. Cruz—who once held a congressional hearing solely to dispute climate change science and who has called global warming a plot by the “radical left” to wrestle control of the economy—gazed blankly up as thunder rattled the skies. Then he silently went back into the house to work.

When the time came to move on to his next event, a Gulf Coast Industry Forum at the nearby Pasadena Convention Center, Cruz emerged from the house with particles of Sheetrock blanketing his sweat-doused clothing. A heavy rain began to fall, drenching him almost instantly. It was the only shower he would get before his Pasadena speech.

Yet an hour later, few among the thousand-strong crowd could have guessed that the politician before them was filthy beneath his blueish-gray suit. Cruz paced the stage and told the story of Hurricane Harvey, recounting the heroism of first responders and Coast Guard personnel, along with “ordinary Texans who went and jumped in a boat to save their neighbor—rednecks in bass boats, the very best of Texas.” There were homeless men in a shelter serving meals, he reminded them, and a church group from the lower Rio Grande Valley who traveled six hours round-trip each day to serve 41,000 meals in Rockport. “It was really the spirit of Texas, as we saw neighbor helping neighbor, friend helping friend, Texan helping Texan,” he said.

As he spoke to both the business leaders in Pasadena and to the Kingwood Area Republican Women later that day, he subtly turned himself into a minor hero of the storm. He told the crowds about serving breakfast at the George R. Brown Convention Center and about speaking to displaced people at a church in Port Arthur. He made a point of saying he had just come from the house in Alvin, and he reflected upon an airboat tour he’d taken down Clay Road, in northwest Houston: “I became a Christian at Clay Road Baptist Church. Clay Road was under eight to ten feet of water.”

He told rapt listeners that as the storm struck, he dialed up Donald Trump: “He said, ‘Ted, whatever Texas needs, you got it.’ ” And he recalled that when Houston mayor Sylvester Turner and Harris County judge Ed Emmett told him they didn’t have enough assets for high-water rescues, “I got on the phone and lit up the phone, speaking over the next several days to the president, the vice president, cabinet members, to the governor. Within twenty-four hours, we had choppers mobilized, we had boats mobilized, we had high-water trucks mobilized.”

Cruz even talked about hugging liberal Democratic U.S. representative Sheila Jackson Lee at a Houston city council meeting as they discussed Harvey relief and recovery. “There are no Democrats. There are no Republicans,” Cruz said to the crowds, sounding a lot like a previous president he’d repeatedly vilified. “We are united as Texans, standing as one.”

In life, the adage goes, it is almost impossible to recover from a bad first impression. In politics, it is even harder.

The impression Cruz made among his fellow senators in 2013 was of a grandstanding provocateur and obstructionist. In his first month in office, Cruz refused to endorse Cornyn’s election as the Republican whip, and he was on the losing side of every single vote in the Senate, including the Hurricane Sandy relief package. That fall, in an attempt to force a vote that would defund the Affordable Care Act, he helped orchestrate a sixteen-day government shutdown, highlighted by a now-infamous 21-hour speech that included a reading of Dr. Seuss’s Green Eggs and Ham.

Cruz’s tea party base was ecstatic. Others were less enthusiastic. For the next few days, a parade of senators, fellow Republicans among them, stopped by to yell and curse at Cruz during lunches on Capitol Hill. When he later questioned the patriotism of Senator Chuck Hagel, a decorated war hero, Senator John McCain compared Cruz to disgraced senator Joe McCarthy. Peter King, the congressman from New York, at various turns called Cruz “a con man,” a “carnival barker,” and a “fraud and a liar.”

Yet for all the frenetic fury of Cruz’s first two years in office, he produced little in the way of legislative accomplishments. Of course, passing legislation was never his intent. I’ve followed Cruz’s career since 2009, when he was considering a run for attorney general of Texas. Though that opportunity never came to pass, Cruz was clearly a man on a mission. He is the only politician I have ever bestowed with a nickname, the Running Man, because he is constantly on the hunt for higher office. Even as he took the oath of office as a senator in 2013, he looked less like someone who wanted to govern and more like a candidate with an eye on a bigger prize. “Clearly he didn’t come here to remain in the Senate,” Cornyn once told a Dallas radio station. “He came here to run for president.”

Trump’s eventual victory over Clinton presented a crisis of sorts for Cruz.

He officially announced his intention to do just that in March 2015, at Liberty University, in Lynchburg, Virginia. At the time, he was considered a long shot for the Republican nomination. “Over and over again, when we face impossible odds, the American people rose to the challenge,” he told the crowd, before making a pledge that remains unfulfilled. “You know, compared to that, repealing Obamacare and abolishing the IRS ain’t all that tough.”

In the campaign’s early stages, Cruz allowed other candidates to attack Trump while he played to the right wing of the Republican base, a strategy that helped him win the Iowa caucuses. In the months that followed, it became resoundingly clear that voters were hungry for a disruptive candidate, and more than any other politician in recent memory, Cruz had already asserted his enthusiasm for upsetting the Washington establishment. He soon eclipsed tea party darlings like Marco Rubio, and as the field of seventeen candidates narrowed one by one, Cruz eventually became the last major obstacle between Trump and the presidential nomination. Yet even the endorsements of fellow Republicans—many of whom had once expressed scorn for Cruz’s tactics—failed to propel Cruz ahead of Trump. Ultimately, Cruz fell to a candidate who outflanked him as an outsider. After losing the Indiana primary in May 2016, Cruz suspended his campaign. At least in an official capacity.

He still believed Hillary Clinton would win the general election, and he planned to spend the next four years positioning himself to challenge her in 2020; the pro-Cruz Trusted Leadership PAC even remained staffed. His Senate colleagues had hoped for a chastened and contrite Cruz when he returned to the Senate floor, but Cruz was defiant. “The media would like to see me surrender the conservative principles that I’m fighting for, join the Washington cartel,” he told Todd J. Gillman, of the Dallas Morning News.

And then came the Republican National Convention. Rather than endorsing Trump, Cruz urged conservatives to “vote your conscience . . . up and down the ticket.” He was quickly booed off the stage. Afterward, Cruz was barred from entering the suite of one of his earliest backers, casino magnate Sheldon Adelson. Another supporter, Robert Mercer, of Long Island, promptly announced that he and his family were “profoundly disappointed” that Cruz reneged on his pledge to support the party’s eventual nominee. Trump’s Texas chairman, Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, hinted that a Republican opponent would be found for Cruz’s Senate reelection if he didn’t endorse Trump.

In September, Cruz finally capitulated. Even then, his Facebook endorsement was more of a diatribe against Clinton than an embrace of Trump. “Our country is in crisis. Hillary Clinton is manifestly unfit to be president, and her policies would harm millions of Americans,” he wrote. “And Donald Trump is the only thing standing in her way.”

Yet Trump’s eventual victory over Clinton presented a crisis of sorts for Cruz. He had made his name as the chief opponent of all things Barack Obama. Now that his party controlled the White House and a majority of Congress, pure opposition was no longer a coherent political strategy. If Republicans failed to pass meaningful legislation, it would reflect adversely on Cruz himself. Could he remain an outsider while embracing Washington insiders in order to fulfill his campaign promises?

In September, half a mile from the nation’s capitol, I sat down with Cruz at Capital Grille, the kind of upscale, white-linen steakhouse that the average American likely imagines when conjuring images of Washington power and influence. Sides of beef were aging in a clear, climate-controlled locker near the front door, miniature lamps illuminated each table, and tan-jacketed waiters greeted Cruz by name. As we talked, a patron stopped by to tell Cruz she was sorry he didn’t win the presidency. Her condolences sounded an awful lot like encouragement.

I was there, in part, to ask Cruz about his Senate reelection. Though his presidential primary campaign raised his national profile, it didn’t boost his standing among Texans. In a survey conducted for the Texas Tribune by the University of Texas, the percentage of Texas voters who strongly approve of Cruz as a senator decreased from 27 percent in November 2015 to 19 percent this October. Overall, 38 percent surveyed in October viewed Cruz favorably, while 45 percent held an unfavorable view. That is not a good starting point for an incumbent senator who faces challenges in both his primary and general election.

Still, barring any unforeseen complications, Cruz is widely expected to win in a rout. “I don’t believe Texans want a liberal Democrat in the Senate,” Cruz explained matter-of-factly when I asked about his probable challenger, El Paso congressman Beto O’Rourke. “Texans want a senator who is leading the fight to repeal Obamacare, who is leading the fight to reduce taxes, simplify the tax code, reduce the burden on job creators, who is leading the fight to reduce regulations that are hammering farmers and ranchers and small business, who’s leading the fight to confirm strong constitutionalists to the court.”

Our encounter that day felt less like an interview and more like a sales job—he was selling himself, selling his ideas. A watch on his left wrist, an activity tracker on the right, he kept folding his hands together as if in prayer, leaning in to punctuate his points, seemingly more directed at the audio recorder on the table than to me. There is no wasted motion in Cruz’s life, and since losing the presidential primary, he hasn’t slowed a bit. To date, he’s done more than two dozen interviews with Fox News in 2017, and in the fall he participated in a series of CNN debates with Senator Bernie Sanders on topics like healthcare and tax reform.

Eventually, our conversation turned to his rumored reinvention. “The portrait of a wild-eyed bomb thrower was always a caricature,” he said, shrugging it off. There is evidence to suggest that Cruz has altered his behavior, however. According to the research firm Quorum, before his presidential run, Cruz voted with the Republican leadership less than 90 percent of the time; in the current Congress, he has aligned himself with party leadership on 100 percent of votes. During his presidential campaign, the nonprofit American Future Fund ran commercials criticizing Cruz for voting against two defense authorization bills, claiming he was weak on the military. Since then, Cruz has voted in favor of every defense authorization bill that has come up.

Our encounter that day felt less like an interview and more like a sales job—he was selling himself, selling his ideas.

I was curious to know how he would continue to curry favor with his core supporters, who have rallied behind his take-no-prisoners persona, while still finding ways to pass meaningful legislation, which inevitably involves compromise. When I posed this dilemma, he reminded me of what he told Fox News after winning his 2012 primary election for Senate: that he is willing to compromise, just on his terms. “My view on compromise is the exact same as Ronald Reagan’s. Reagan said, ‘What do you do if you’re offered half a loaf? Answer: you take it, and then you come back for more.’ ” He turned away from the recorder and looked directly at me. “I will happily compromise with anybody: Republican, Democrat, independent, Libertarian. I joke, heck, I’ll even compromise with martians. What I’m not willing to do is compromise in a way that makes the problem worse.”

The difficulty, of course, is that this philosophy has led to a dismal legislative track record. Through almost five years in the Senate, Cruz has carried exactly two bills that became law. The first, passed in 2014, bars United Nations representatives who have committed espionage or terrorism against the U.S. from entering the country. The other was a 2017 act that authorized NASA funding for that fiscal year (Cruz was chairman of the Senate subcommittee that oversees NASA).

He took credit for 2015 legislation aimed at stimulating commercial space traffic, though he wasn’t actually its author (he negotiated an amendment that melded two other pieces of legislation into the bill). On multiple occasions he’s also taken credit for securing federal spending in Texas through amendments to National Defense Authorization Acts, despite ultimately voting against those same bills. In 2016, after he protested a provision in a defense authorization bill that required women to register for the draft, the legislation’s sponsor, McCain, sarcastically quipped that Cruz has a “unique capability” to pick one issue in a complex bill and then take a “strong moral stand.”

Yet last spring, during the healthcare debates, it appeared at times that Cruz was more willing to negotiate. He worked with moderate Republican senator Lamar Alexander and others to try to find common ground, for example. On the other hand, he also advised the House Freedom Caucus on problems he saw in an overhaul bill promoted by Paul Ryan, so when that bill failed, some in the House blamed Cruz. “He’s definitely a hindrance,” Republican representative Chris Collins, of New York, told the Dallas Morning News. “He spends more time in the House with the Freedom Caucus than in the Senate because nobody likes him in the Senate, and that hasn’t changed.”

Then, months later, Cruz joined with Senator Mike Lee to present an alternative plan. Their Consumer Freedom Amendment would allow insurance companies in the individual marketplace to offer plans that don’t meet Obamacare mandates, as long as they offer at least one plan that does. The rationale was that options would drive down costs. Many experts, however, argued that people with chronic health issues would be forced into costly plans while young, healthy consumers would flock to cheaper options. One study also found that it would leave an additional four million Americans without health insurance. The insurance industry opposed the plan, fearing it would destabilize insurance markets. Thus, although Trump and the Department of Health and Human Services supported the Cruz amendment, the final repeal effort crafted by Senators Lindsey Graham and Bill Cassidy excluded his proposal. As a result, Cruz refused to support their bill. By that point, however, it was clear that the legislation was doomed, meaning Cruz could feign a principled stance without actually derailing the repeal.

When tax reform came to a vote in early December, though, he was faced with a starker choice. Republicans, including Cruz, had long made tax reform a top priority, but when the hastily conceived Senate bill was analyzed by the Joint Committee on Taxation, it concluded that the proposed legislation would add $1 trillion to the federal budget deficit. Cruz, who had often obstructed bills, including Hurricane Sandy relief, purely on the grounds that they increased the deficit, still voted yes after being offered an amendment that would expand the use of 529 savings plans from college to also include K–12 school tuition (a boon for school choice, another Cruz priority). When asked about his vote, he claimed that the committee’s deficit report was “exceptionally shoddy, and I don’t believe it is credible.” He also argued that it didn’t sufficiently account for the economic growth that would result from the tax cuts.

In the days after the bill was passed, however, the New York Times reported on the systematic Republican effort to undermine the Joint Committee on Taxation, a nonpartisan agency that the GOP had long championed. It’s likely that Republicans spurned the agency because they badly needed a legislative victory, but even if the committee’s report was flawed, the bill still appeared remarkably similar to the kind of “Christmas tree” legislation Cruz excoriated after Sandy.

What does this reveal, if anything, about Cruz’s positioning during the Trump administration? In the fall I had called Steve Deace, a Christian conservative talk radio host in Iowa who helped deliver his home state to Cruz in the Republican caucuses. He protested that the 2.0 notion is meant to cut Cruz down. “The system’s number one goal is to show that it can co-opt anybody,” Deace said. “It can corrupt everybody. No one can stand up to it, and they have had this story written of Ted Cruz 2.0 for over a year.”

But others are willing to concede the necessity of changing tactics. “The failure of the leadership in both the House and Senate is abundantly clear,” said JoAnn Fleming, executive director of the East Texas tea party group Grassroots America. “We don’t need Senator Cruz to be calling them out every fifteen minutes on the floor of the Senate anymore.” Yet Cruz is still a warrior on the important issues, she maintained. “The way he fights for them has to be a little bit different.”

Jeff Roe, the big-data guru of the Cruz political operation, told me that Cruz has gone from “fighting tooth and nail” to prevent bad legislation to “fighting tooth and nail to get good reforms done, and that requires a different skill set.” The political landscape has shifted, he said, and then offered an analogy that many Texans will appreciate. “I mean, if you’re a passing quarterback who goes to a running quarterback program, you better learn how to run the ball. And if you’re a running quarterback and you’re going to a spread offense, you better learn how to pass the ball.”

But I was also reminded of a story that Cruz told me at the Capital Grille, about meeting with grassroots activists during his first Senate campaign. “I still remember a little old lady from East Texas,” he recalled, “who grabbed me by the shoulder and said, ‘Ted, please don’t go to Washington and become one of them.’ ”

A few months before the tax reform vote, some four hundred people gathered in the sanctuary of Grapevine’s First Baptist Church to hear Cruz speak. The stage’s backdrop was illuminated in muted blue and red tones, like an electric stained glass window, and two big-screen TVs projected the logo of the Northeast Tarrant County Tea Party, a Texas flag with the Don’t Tread on Me snake replacing the lone star. Around 3:00, Maggie Wright, a Burleson housewife who is perhaps Cruz’s top fan and advocate, emerged to warm up the crowd. Wright volunteered for Cruz during his first run for Senate, and at one point spent 51 days living in an Iowa dormitory to help promote his presidential campaign. Her SUV, parked out front, boasted a “Cruz 20” license plate and was wrapped in several decals, including a screaming eagle on the hood that read, “America, it’s time for Cruz Control.”

Wright regaled the audience with tales about what it was like to follow Cruz across the country during the presidential campaign, but mostly she talked about bystanders’ reactions to the car. “Everywhere we go, when we park, people take a look,” she said, pausing for effect. “But when we park at Walmart, they’ll come running over. ‘Is Ted in there?’ ”

The crowd guffawed. Wright then grew serious, painting Cruz as a compassionate man, contrary to the venomous firebrand his critics see. “They’ve just seen the fighting side. They only see the throwing sand in the gears,” she said. “But Ted has really been there for the citizens of Texas.”

Cruz was greeted with rapturous applause when he came onstage. He spoke for more than an hour, offering a truncated version of his hurricane speech before weaving a self-portrait of a steadfast conservative. Still, he added, there is only so much one man can get done. “Am I the only one here frustrated with Congress?” he asked. If Republicans don’t fulfill promises to repeal Obamacare and overhaul the nation’s tax structure, he said, they are looking at a “bloodbath” in the 2018 midterm elections. Now is the best opportunity for “historic” tax cuts, he argued. “I believe we will get tax reform done,” Cruz said.

No more was Cruz the angry man standing in the Senate well castigating his fellow Republicans.

“In my lifetime?” shouted a man from the audience. “How old are you?” Cruz quickly retorted.

While describing his allegiance to conservative values, Cruz also offered a nuanced description of all the ways he is working to make compromises on legislation. “As frustrated as y’all are, I’m sitting there every day. I’m banging my head into this every day.”

He talked of how he had joined with other Republican senators to form an Obamacare-repeal working group, and of how he and Mike Lee later partnered up in pursuit of a compromise on the Lindsey Graham–Bill Cassidy repeal-and-replace bill, which ultimately failed to come to a vote. Cruz also noted that in July the Senate failed by a single vote to pass a bill that would have partially repealed Obamacare. “I’ll tell ya, when that happened, I had to turn and leave the Senate floor, because if I’d stayed on the Senate floor I would have said some things to my colleagues that were not appropriate to say.”

No more was Cruz the angry man standing in the Senate well castigating his fellow Republicans. There was even a hint of resignation in his voice as he noted that there are three Republicans firmly against repeal. “So where do we go from here?” Cruz asked. “It’s not easy to see how to skin that cat.” He didn’t promise that repeal would happen, only that “every ounce of my body” will be used to find the votes.

During the question-and-answer session, members of the crowd roared angrily about immigration and trade and the feckless leadership of their party. “Republicans are now Democrats!” one shouted. But their anger was never directed at Cruz. He was one of them.

After his speech, Cruz held court at the front of the sanctuary while tea party members lined up to take a picture with him. One after another, people who had complained minutes earlier about the ineffectiveness of Washington now shook his hand and commended him. The last person in line was Patricia Cole, a Republican candidate for Tarrant County probate judge. “Mr. President,” she said, holding out her hand.

Cruz bowed slightly in her direction. “Thank you very much,” he said.

“I’m sorry you didn’t make it,” she added.

“It was an amazing journey,” Cruz reassured her. “Heidi and I are immensely grateful for having had the opportunity.”

But that was the past. I still wanted to know about his future.

“Life is long,” he told me, “and we will see what the future holds. My focus right now is on fighting for the very same principles that were at the heart of the presidential campaign, which is defending freedom and the Constitution, fighting for jobs and economic growth and opportunity so that more and more people can have a chance at the American dream. And we have a historic opportunity to deliver on those promises right now. The Senate is the battlefield for every one of those. And so that’s my focus. But I’ll say at the same time I’m committed to the long-term journey.”

I reminded him that, even if he has to wait eight years to run again, he would only be 53, still young for a presidential candidate. A massive grin stretched across his face.

“Life is long,” he replied.