The day before he presented a painting to Derek Jeter of the New York Yankees, artist Opie Otterstad described the hundreds of celebrities he’s befriended over the years. He laboriously studies his subjects, going to their houses or calling organizations they’ve been affiliated with to ask for paraphernalia. He even goes so far as to mix dirt from a person’s home state into the paint he plans to use. His efforts pay off: He has brought athletes to tears with his work.

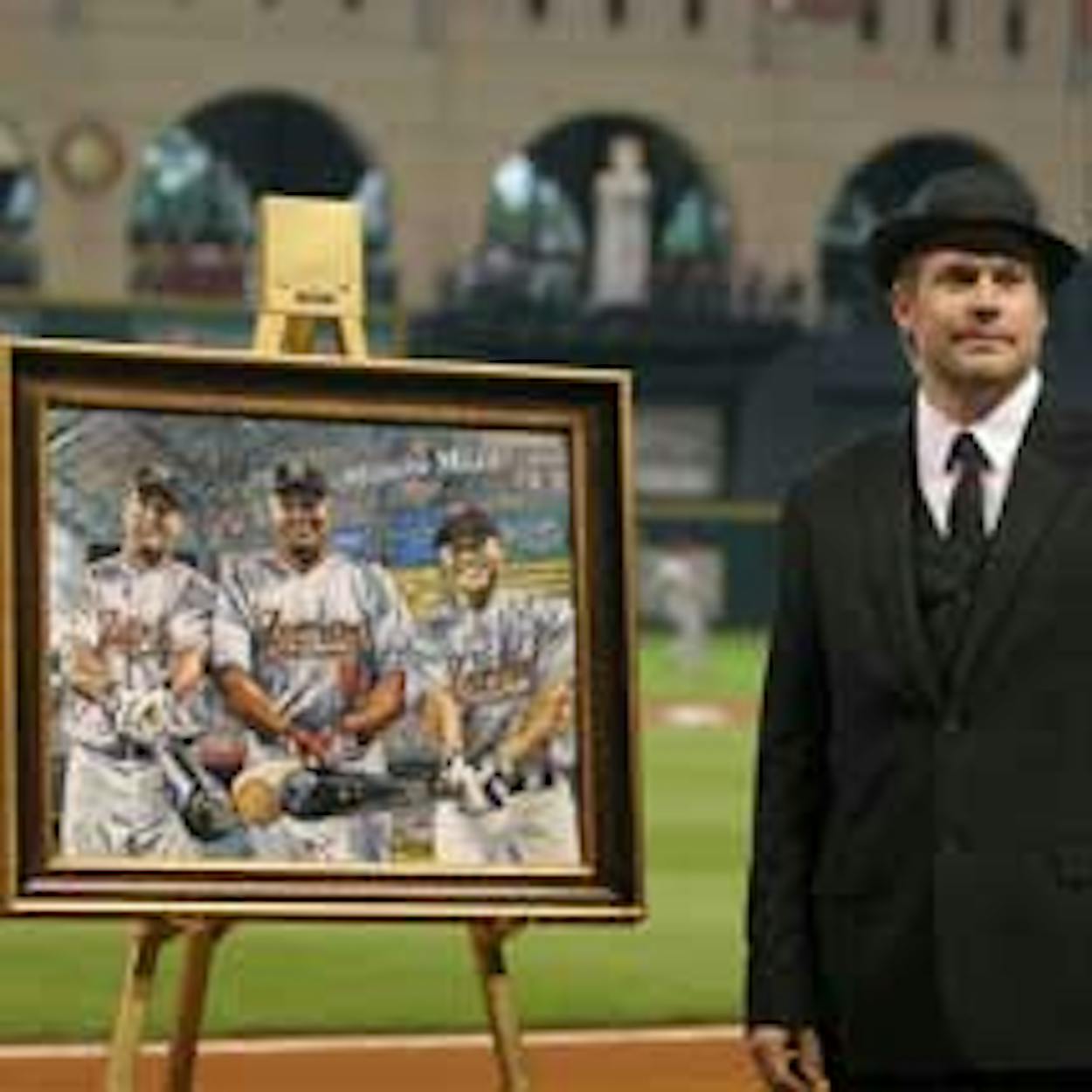

The 39-year-old official artist of the Texas Baseball Hall of Fame has hundreds of patrons—including three presidents—whom he calls friends. He finds fellow Texans everywhere, even at a Philadelphia Phillies game for opening day, with a simple question, “Where y’all from?” We chatted with Otterstad about how he got started and why he considers himself a true Texan.

Tell us about the painting you will present at Yankee Stadium.

It’s in my nature to make things more complicated than they need to be, and I had twelve working days before its delivery. I went through 12,000 photographs looking for specific information on the gloves, bats, and special things the catcher and umpire had on [when Derek Jeter broke former New York Yankees player Lou Gehrig’s hits record]. If I can’t find what I’m looking for, I go to the athletes themselves. I got the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Louisville Slugger involved and ordered specially made bats to incorporate into the painting. I mixed the sawdust of a piece of Lou Gehrig’s bat and dirt from the old and new Yankee stadiums into the paint. This adds to the story of the painting and gives it part of a soul.

Have you ever thought of painting without doing any research?

I don’t want the painting just to tell a story. I want the painting to be a story. I want one of my pieces of art to stand alone as a beautiful painting, and I want you to stand in front of the piece of art and tell a story about the artist, about the things you see and the things you don’t see. If I’m painting someone from California, I want the wood to be from California and to mix in some dirt from California. I pick up stuff wherever I go. I have dirt from every stadium I’ve ever been in—all labeled—in case I want to make the painting into more of a story.

You really enjoy this.

I’m like a professional year-round Santa Claus. I sit in front of the canvas for a living and do whatever I want to do. There are no bounds to creativity. I’m like Dr. Frankenstein in Photoshop. If I don’t have an arm in the right place, I’ll light it just right and put my arm and leg in that. I get some wild, crazy, hair-brained ideas to show something in a very unique way, and that’s the patron base I’ve established. They expect me to come up with something that’s going to bring their wife to tears. Working in sports has given me these wonderful, amazing opportunities. I also did a piece on George H. W. Bush in his 1948 baseball uniform.

How did you get started?

I went to St. Olaf College, a Lutheran school in Northfield, Minnesota, and majored in studio art and psychology. During the summer I would sit at the front desk doodling and drawing at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, and Fran Pirozzolo, a sports psychologist, once asked, “Opie, do you just draw or do you paint?” He wanted to see some of my work, so I brought it in. Some of my first commissions were for Evander Holyfield, Greg Norman, and Paul O’Neill, a baseball player with the Yankees at the time. Once one or two athletes have your work, there’s some acceptance that goes on. I met the athletes when they played for Texas, and they’ll go somewhere else, sit on the bench for three to four hours every day, and the conversation continues. I have a wonderful network, and the American sports community in actuality is pretty small. If you want to trace the Derek Jeter painting, go to Andy Pettitte from Houston.

What’s one of your favorite reactions to your work?

Ben Crenshaw, a golfer from Texas, literally wept, and every time I see Ben to this day, he sticks out both of his hands and says, “Opie, it is so good to see you” and talks about the painting at the end of his hallway that he sees every day. Craig and Patty Biggio in Houston have purchased almost fifteen pieces over the past seventeen years. I think Craig, who played with the Astros for twenty years, has cut off Patty from buying more.

How do you embrace your identity as a fourth generation Texan?

The wonderful thing about being from Texas is the old adage, “You can take the boy out of Texas, but not the Texas out of the boy.” It’s more a state of mind than a state. A great deal of my work comes from Texas teams: the Rangers, the Rockets, the Stars, and the University of Texas football team. With my career, it’s like seven degrees of being a Texan. It’s like being in a fraternity. If you’re from Texas, it doesn’t matter where you go or what you do—you instantly have something in common with other people.

You could live anywhere. Why Austin?

If you pick where to live in Texas, you live in Austin. There are a lot of artists and creative thinkers. I spent a few early years in Waller, but we moved to Houston when I was in fourth grade. My parents have been there ever since. I’m literally in either Houston or Dallas every other week because of work. My birth mother lives in Dallas, so I’m a Texan all the way through.

How do you maintain your individuality?

I’ve always done things my own way. I don’t take criticism very well, so I maintain strict autonomy on the project if I’m working on commission. It says a lot about where I’m from, because in Texas we do things our own way. You can trace most of my private sales to Texas connections by two or three degrees of separation. We have a rebellious streak in us, and that’s special.

You have more than 35 fedoras and about twenty vintage Pendleton jackets—most from eBay. Why are these items significant to you?

The first person that I knew who wore a fedora regularly went to our church in Waller. He adopted me into his family like a grandson. My mom usually had something to do during church services, and my dad was up in the pulpit, so I’d spend time with him and his family. He’d sit down in the pew, fold his handkerchief, and lay his hat upside-down on top of it. It was a beautiful ritual, and I always had an affinity for that kind of hat. It just fit how I felt. I also keep a handkerchief in my pocket, and every time I take off my hat, I do the same ceremony. I met some of my best friends at Camp Chrysalis in Kerrville, and one gave me his father’s black fedora. I’ve been wearing a fedora ever since.

When I was sixteen, I fished my first Pendleton coat out of my dad’s old clothes. I always wear a fedora and almost always wear a vintage Pendleton coat from the late fifties and early sixties. People who don’t know what I do say, “Oh yeah, you look like an artist.”

You come from a family with six generations of ministers. How do your parents feel about your decision to become an artist?

My dad’s side of the family always hoped I would go into the ministry. In a Scandinavian household, you find out how your parents feel about you by asking their friends, and they’re ridiculous about it with them. It’s good for your folks to be proud of you and to support you. They’re over the moon about it.

You ask baseball players to sign your bats. What’s the most memorable note you’ve received?

A few years ago, I asked Lance Berkman of the Astros to write something for me. Lance came up with tiny writing that covered the whole bat. The opening line was, “To the People of Texas and all Americans in the world,” and he continued with Travis’s letter from the Battle of the Alamo. I’m sure it was a very long letter, so he thought it was very funny. I treasure it to this day because it’s very unique and very Texas.