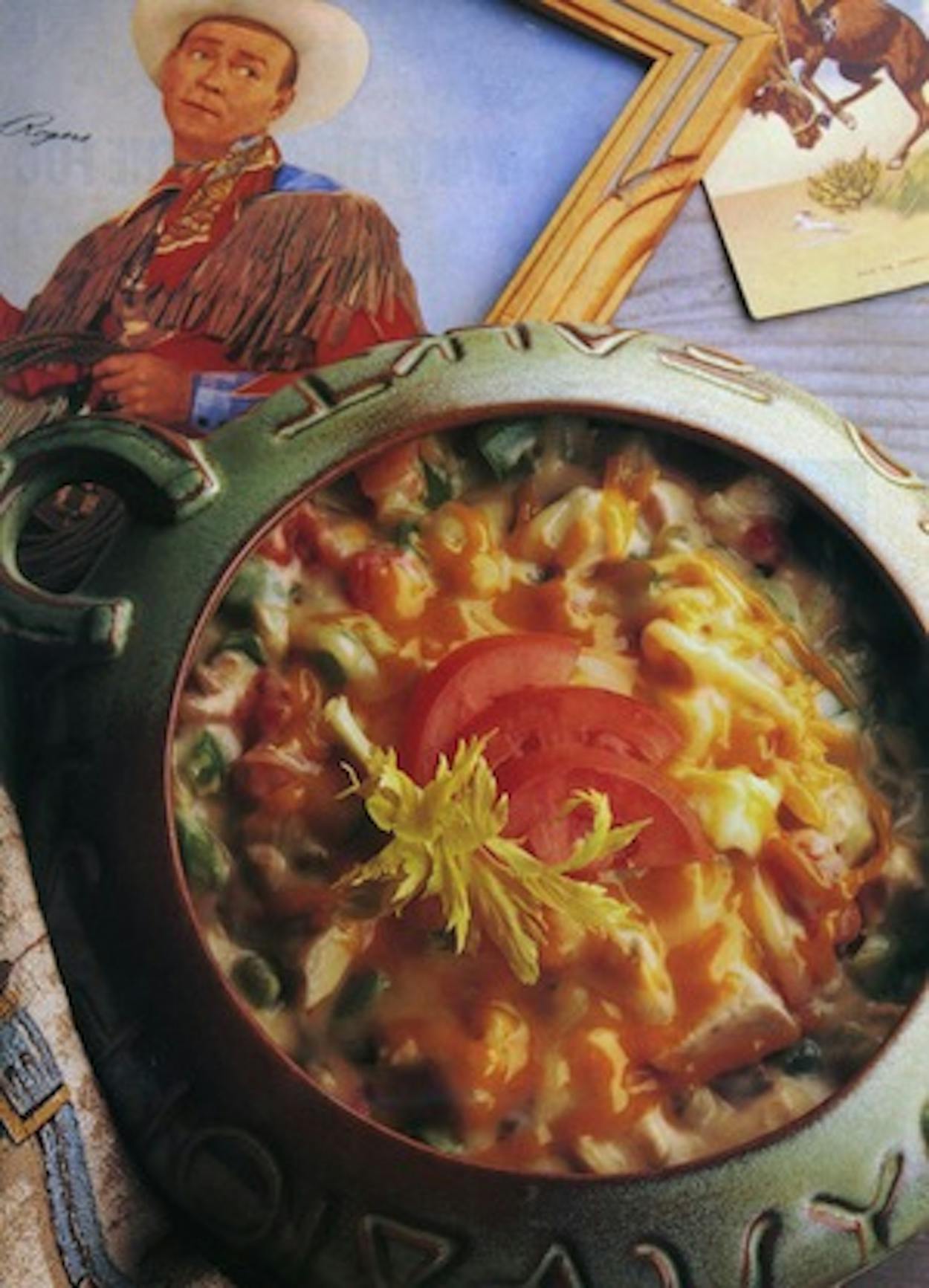

King Ranch Casserole is not a pretty dish. A steaming mass of melted mush, the classic ingredients—boiled chicken, grated cheese, tortilla chips, and one can each cream of mushroom and cream of chicken soup—make it a study in beige and yellow. Nor is it at all exciting: Even with the requisite Ro-Tel tomatoes and green chiles, the flavor is resolutely bland, a quality Texans claim to abhor in their cooking. The dish is, in fact, the subject of some scorn: “Never, never, never,” says caterer Tilford Collins, who serves some of South Texas’ oldest families. Texas food historian Mary Faulk Koock is only slightly more charitable. “I imagine it could be made palatable,” is about all she has to say on the subject.

Still, King Ranch casserole—or King Ranch chicken, as it is often called—has endured. It is the clubwoman’s contribution to Texas cuisine, a staple of society ladies’ cookbooks from Fort Worth to McAllen, where the Junior League’s La Piñata touts a variation as a “great way to enjoy that leftover Christmas or Thanksgiving turkey.” The casserole’s fame has spread to cookbooks in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Kansas, and the dish can be purchased frozen from Randall’s supermarkets in Houston and from H.E.B. in Alamo Heights. Not only is King Ranch casserole the most requested dish at the 1886 Room, Austin’s premier ladies’ lunch spot, but it is also popular at trendy Brazos on Greenville Avenue in Dallas, where needy singles demand it at the end of particularly punishing work weeks. “It’s Mom food,” says Brazos owner Nancy Beckham, who ate the dish as a child in both South and West Texas in the fifties. Forget the spare sophistication of nouvelle cuisine, the assertiveness of true Mexican cooking. The secret of King Ranch casserole is that it’s boring. In today’s complex culinary lexicon, the dish resides snugly in the category of comfort food.

No one seems to know who invented it. The casserole may have come from the King Ranch, but the descendants of Captain Richard King prefer to tout their beef and game dishes. “Kind of strange, a King Ranch casserole made with chicken,” notes Martín Clement, the head of public relations for the ranch. Mary Lewis Kleberg, the widow of Dick Kleberg, admits her heart sinks every time a well-meaning hostess prepares it in her honor. Most likely the dish got its name from an enterprising South Texas hostess or a King Ranch cook whose preference for poultry doomed him to obscurity.

Yet King Ranch casserole’s general origins are easy to discern. Certainly it owes a deep debt to chilaquiles, which also contain chicken, cheese, tomatoes, tortilla chips, and chiles—the staples that campesinos often combined to stretch one meal into two while retaining a semblance of nutrition. But the dish owes as much to post—World War II cooking, when casseroles made with canned soups were the height of space-age cuisine. Because they could be made quickly and frozen for later use, casseroles liberated the lady of the house. “The perfect entrée for a minimum amount of time in the kitchen for the hostess,” the McAllen Junior League cookbook notes. The recipe made its way from one women’s club to another, networking in its most fundamental form. “It was one of those recipes that everybody just had a screaming fit trying to get,” Mrs. Joe Gardner of Corpus Christi recalls.

If the women of the fifties loved the recipe because it freed them from the family kitchen, their children love it because it takes them back there. They have adapted it to their taste, of course: Trendy cooks now substitute flour tortillas for corn, while the truly convenience-crazed use Doritos. Purists doctor the recipe with sour cream—a move back toward Mexican authenticity. Houston’s Graham Catering has come up with a low-salt version. Even that bastion of Junior Leaguedom, San Antonio’s Bright Shawl lunchroom, has changed with the times. Chef Mark Green has followed the lead of the late Dallas gourmet guru Helen Corbitt by dropping the canned soups; he now adds his own “roux” of milk, shredded cheese, garlic, and sliced mushrooms. “It sells good,” he says. “It goes fast.”

Even with modernization, the dish still tastes pretty much like it used to—slightly salty, slightly chewy, slightly spicy, slightly greasy. Yes, it lacks the challenge of a T-bone or a spicy bowl of red—King Ranch casserole calms, it does not wish to offend. What better dish to end the old year and face the one to come?