This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

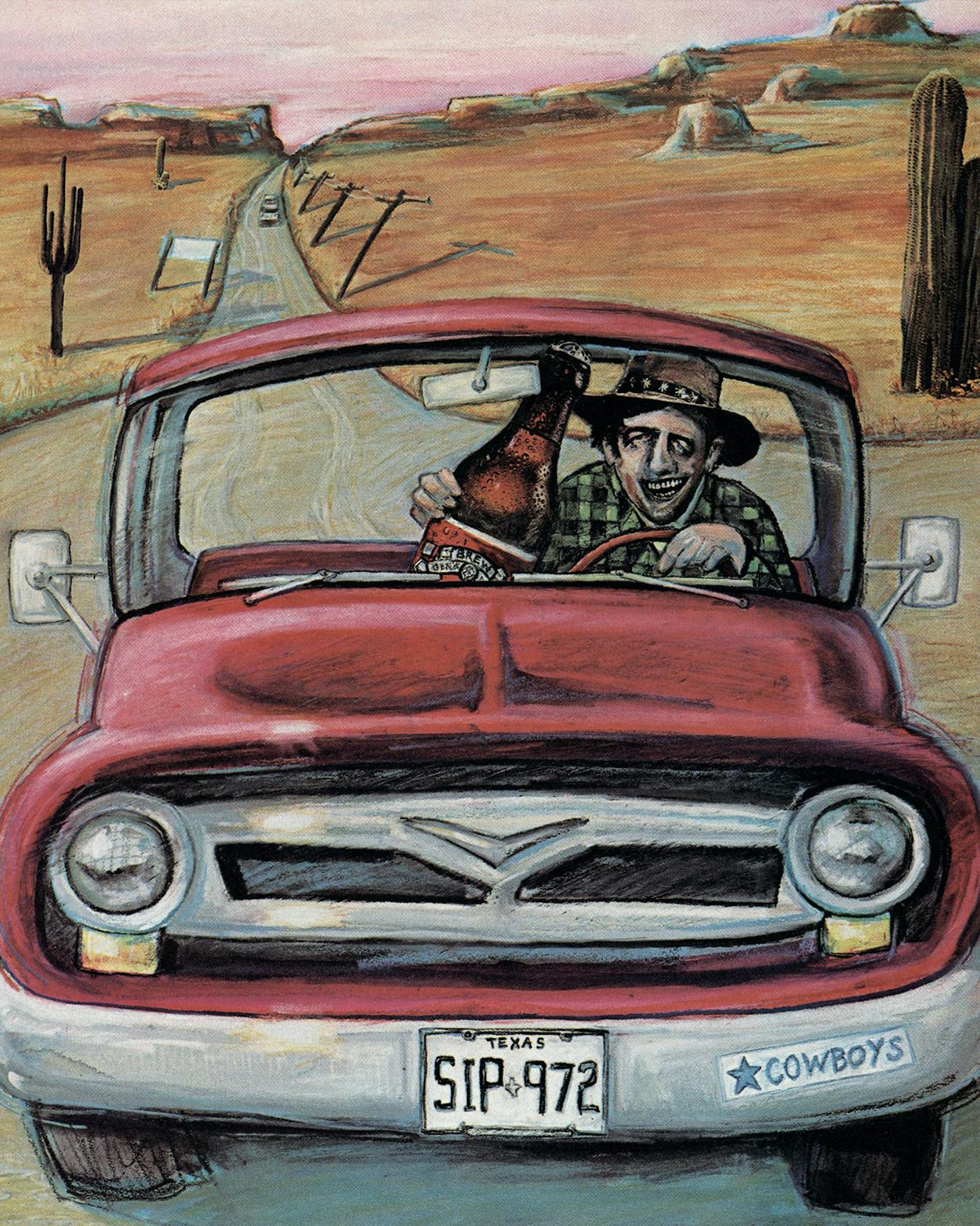

Hey, Agnes. Bring us a couple more.” A dry wind pops the canvas of the awning as the carhop ambles across the hot tarmac with her tray aloft, the only relief in sight those cold brown bottles of beer. Ah, one for the road. But in Texas that doesn’t mean the last one you drink before you leave; it’s the one you take with you for the long drive home. Newcomers to Texas often gape at people who calmly drink beer as they drive along. In most states, an open container of alcohol is something that drivers and passengers hide from view, if they take the chance of carrying it at all. Texans love to drive and drink. I’ve done it many times, and the odds are, so have you—gained new vigor for the upcoming stretch of road from the rousing feel of a cold one wedged between your thighs.

Nobody is sure how the tradition started, but symbols of our social irresponsibility abound: Lyndon Johnson bouncing with foreign diplomats through the pastures of his ranch, beer in hand; Paul Newman in Hud, ordering a fresh brew from Patricia Neal’s grocery sack while the Cadillac billows dust. Though Texas is now the third-most-populous state, we cling to our rural past, when it was hard to make the time pass on long stretches of lonesome road. We’re not too inclined to break old habits. However destructive in potential—25,000 alcohol-related highway deaths occur in this country every year—the freedom to imbibe behind the wheel represents a level of personal liberty that is denied residents of more thoroughly urbanized parts of the country. We tenaciously defend our right to drink and drive, at least up to a point: one tenth of one per cent alcohol in the bloodstream.

Other populous states have concluded that individual judgment is not to be trusted and prohibit drivers from drinking or ban open containers altogether. Residents of California, New York, and Illinois shudder at the thought of being pulled over with an open beer in the car; they may be fined up to $500. Texas, with no statutes against open containers, remains one of the few states where drinking while driving is perfectly legal. In 1983 Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) tried to push a package of stiff drunk-driving penalties, including a $200 fine for open containers, through the Texas legislature. The beer lobby argued that Texans weren’t about to change their ways because of a law. If the situation required it, the offenders would just throw the bottles and cans into the nearest ditch, adding to the litter problem. The legislators passed most of the measures MADD wanted, but the open-container proposal went nowhere.

The most telling contemporary symbol of our recalcitrance is the convenience store that sells gasoline and beer. Six-packs and singles chill down right next to the soda pop, and you can buy those insulated sleeves to keep your beer cold almost anywhere. The production of attendant paraphernalia has become big business; even Skoal, the snuff company, has distributed them. (The implied mingling of juices is too brackish to contemplate.) Last spring a politically inspired variation began to show up in stores around Dallas–Fort Worth. In anticipation of an open-container bill that would force Texans to resort to subterfuge if they wanted to drink and drive, some good ol’ boys manufactured a sheet of Mylar that clamped tight around a beer can, making it look like a soft drink. They figured there would never be a law against turning soda pop bottoms up in a highway patrolman’s view. Those good ol’ boys were looking to get rich.

I used to frequent a package store, a mom-and-pop affair, on a rural highway southeast of Austin. The old man and I would chat about the weather, his recent operation, the expanding waistline of his Siamese cat. Please believe me, I never broke the seals of my bourbon and gin until I was safe at home. But he always asked me, “Can I give you a cup of ice?” He was just being neighborly, hoping to see me happily on down the road.

- More About:

- TM Classics