Theodore Roosevelt had been enthralled with the idea of Texas since 1883, when he arrived in the Dakota Territory to ranch cattle. To Roosevelt, the outdoors brought spiritual renewal to city dwellers, and many of the Badlands cowboys he encountered spoke of the Hill Country as a hunter’s paradise, teeming with big-bodied deer. It wasn’t until nine years later, however, as the U.S. civil service commissioner, that the 33-year-old visited the Lone Star State for the first time. Officially, he came to investigate the case of a few U.S. postal employees who had been dismissed for purely political reasons. But he also made sure to arrange for a six-day collared peccary hunt that would enliven The Wilderness Hunter, the outdoors memoir he was writing. Furthermore, Roosevelt was planning to anchor future installments of his massive history of the frontier, The Winning of the West. “The next volumes I take up I hope will be the Texan struggle and the Mexican War,” Roosevelt wrote to his friend Madison Grant. “I quite agree with your estimate of these conflicts, and am surprised that they have not received more attention.”

After discovering no peccaries—or “javelinas,” as they are known in Texas—along the Frio River, the Roosevelt party headed south along the Nueces River toward the oak-motte prairies of the Gulf Coast near Corpus Christi. The spring air was mild at Choke Canyon, and he was delighted with seeing so much unexpected greenery. Little brown swifts dashed in front of his horse at regular intervals as he moved seaward, warding off stinging ants. The horseflies were the biggest he had ever seen. The insects were such a serious problem for Texas settlers that screens covered house windows and smoking coils were lit to fend off the swarms. Roosevelt copiously noted the lilac-colored flowers and wide bands of wildflowers that carpeted the unobstructed prairie. “Great blue herons were stalking beside these pools, and from one we flushed a white ibis,” he wrote.

Once Roosevelt had absorbed the Nueces River area in exacting detail, the expedition went onward with trophy-hungry determination. Killing a peccary during the Gilded Age wasn’t easy. In addition to being elusive, peccaries were fierce fighters that traveled in packs, known to slash horses’ legs with their daggerlike tusks and stampede over dogs in dense thickets of chaparral and scrub oak. “They were subject to freaks of stupidity, and were pugnacious to a degree,” Roosevelt wrote. “Not only would they fight if molested, but they would often attack entirely without provocation.”

At sunrise the hunting party was greeted by the Texas nightingale, or mockingbird, and at sunset by the howls of coyotes. But no javelinas. Just when the hunting looked bleakest of all, however, Roosevelt suddenly stumbled upon his mark. A sow and a long-tusked boar turned their huge heads toward the men, grinding their teeth so loudly it produced a sound like the clicking of castanets. Their eyes had that dark, calmly menacing look of great white sharks as they circle their prey. Roosevelt killed them both with his gun at point-blank range.

That evening the hunting party feasted on peccary, and Roosevelt shipped his trophy heads back to New York. More than anything else, it seemed, Roosevelt thoroughly enjoyed the tough talk of his Texas compadres. Like a mynah bird, Roosevelt had picked up a lot of sayings and brags, which he constantly repeated back in Washington. He admired, for example, the story of a Texan who carefully studied a tenderfoot’s .32-caliber pistol and said, “Stranger, if you ever shot me with that, and I know’d it, I would kick you all over Texas.” As a corollary, Roosevelt decided that when it came to peccary hunting, guns weren’t the armament of choice. “They ought to be killed with a spear,” Roosevelt wrote to his British friend Cecil Arthur Spring-Rice. “The country is so thick, with huge cactus and thorny mesquite trees, that the riding is hard; but they are small and it would be safe to go at them on foot—at any rate for two men.”

Roosevelt didn’t return to Texas for six years. This time it was war, not wild animals, that brought him back. No leading American was more gung ho to fight Spain following the explosion of the U.S.S. Maine, on February 15, 1898, than Assistant Secretary of the Navy Roosevelt. Pestering everybody he knew in a position to help, Roosevelt kept pleading, “Send me.” Picking up on the old battle cry “Remember the Alamo,” Roosevelt was one of the chief progenitors of the new slogan “Remember the Maine.” When Secretary of War Russell Alger called for volunteer regiments “to be composed exclusively of frontiersmen possessing special qualifications as horsemen and marksmen,” Roosevelt leaped at the opportunity. Eventually he was tapped as second in command of the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry, behind his friend Colonel Leonard Wood, an ex-Indian fighter who had won the Medal of Honor for pursuing Geronimo. Because of Roosevelt’s highly publicized enlistment, more than 23,000 applicants flooded into the War Department office. Everybody, it seemed, wanted to serve with Roosevelt leading the charge.

With the newspapers cheering, Lieutenant Colonel Roosevelt chose a top-notch regiment of more than 1,250 men. They were first called Teddy’s Texas Tarantulas and went through three or four other monikers until Roosevelt’s Rough Riders stuck. The men were assigned to San Antonio as their mobilization site. The regiment’s encampment was erected on the dusty International Fair Grounds (later renamed Roosevelt Park). A table was set up on the outdoor patio of the Menger Hotel for men to register; some gave pseudonyms so as not to be held accountable for past crimes. Horses and equipment were supplied from Fort Sam Houston’s quartermaster depot. Stetson-hatted men milled about El Mercado, gossiping with Mexicans about glorious wars. Slouch hats, blue flannel shirts, and bandannas were handed out to Rough Riders as uniforms, giving the regiment a distinctive cowboy look.

Roosevelt’s favorite haunt while in San Antonio was the Buckhorn Saloon. Opened in 1881 by Albert Friedrich—whose father made horn furniture of high artistic quality—the bar had a standing offer from day one: “Bring in your deer antlers, and you can trade them for a shot of whiskey or a beer.” Before long the Buckhorn had the finest collection of trophy mounts in the world. Men would actually collect an antler shed from the Hill Country, then ride into San Antonio for their free drink. In 1882, in fact, Friedrich acquired a record-making 78-point buck for $100; it was placed behind the bar, where it remains. Business was so good that Friedrich moved his operation to larger quarters at Houston and Soledad streets, just blocks from the Alamo. Even though Roosevelt wasn’t much of a drinker, he would wander in with his fellow Rough Riders, order a beer, nurse it, and listen to an old guitar picker sing about being a cowhand along the Brazos River.

The regiment’s chant soon became “Rough, tough, we’re the stuff. We want to fight and we can’t get enough.” Throughout San Antonio, signs welcomed each state and territory with hospitality. The Menger Hotel—built 23 years after the fall of the Alamo—housed a replica of the pub inside Great Britain’s House of Lords; bartenders used to give out free shots of whiskey in solidarity with the men (the hotel later named the room the Roosevelt Bar). However, Colonel Wood upbraided the much younger Roosevelt for purchasing beer kegs for volunteers. “Sir,” Roosevelt said when reprimanded, “I consider myself the damndest ass within ten miles of this camp.”

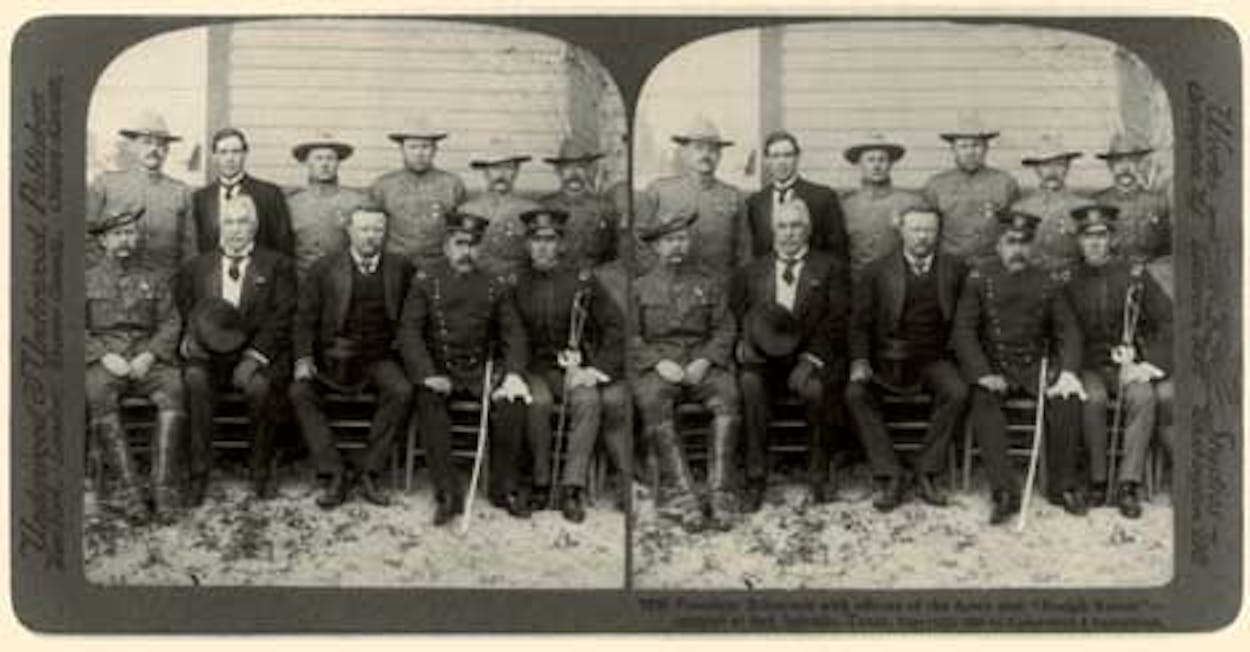

The Rough Riders brought honor to San Antonio by winning battles in Cuba throughout the summer of 1898, and Roosevelt became a Texas folk hero overnight. The next time he visited the state, in April 1905, he was president, and he was treated as if he were the reincarnation of Davy Crockett. An estimated 30,000 people came to Dallas to hear him orate about the American century. Playing his Lone Star chauvinism card, the president called Texas a “mighty and beautiful state” and a “veritable garden of the Lord.” Cultivating local pride, Roosevelt boasted that he was half Southern Gray (mother from Georgia), half Northern Blue (father from New York), but all Lone Star.

The following day Roosevelt visited Waco and Austin, ending up back in San Antonio, at the Menger Hotel. An immense crowd poured out from around the battle-scarred Alamo all the way to the field behind the railroad depot to hear the president deliver a speech—a hymn, really—to the American spirit. “We must handle ourselves so that no weak power which is behaving itself shall have cause to fear us,” Roosevelt thundered, “and no strong power of any kind shall be able to oppress us or wrong us.”

At Fort Sam Houston, Roosevelt inspected the troops and again spoke of the Monroe Doctrine as a guiding American principle. He also intoned about restoring moral credibility to a corrupt Wall Street. On every street block Roosevelt was feted as a hometown boy made good. Along with New York and North Dakota, this was his third adopted state. A major thoroughfare had even been christened Roosevelt Avenue in his honor. Roosevelt acted as if dusty ol’ San Antonio were the greatest place on earth. “In the old days in Texas I understood that there used to be a proverb that while you would not generally want a gun at all, if you did want it, you wanted it quick and you wanted it very bad,” Roosevelt twanged to a crowd of well-wishers. “That is just the way I feel about the Navy. I feel that if we have it, the chances are that we will not need it. But that if we do not have it, we might need it very bad.”

From San Antonio it was on to Fort Worth and Wichita Falls, where some of the largest cattle ranches in the world were found. Two “old style Texas cattlemen,” as Roosevelt described them—Burk Burnett and W. T. Waggoner—were going to lead the presidential hunt to the Big Pasture, near Fort Sill, Oklahoma, to exterminate gray wolves and coyotes as part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Bureau of Biological Survey predator control program. Taken together, the two pro-Roosevelt ranchers practically owned Fort Worth.

In anticipation of the hunt, Jack “Catch ’Em Alive” Abernathy, of Bosque County, scouted the most desirable places to camp in the Big Pasture. Abernathy’s specialty was leaping off a horse, tackling a wolf, and then subduing the animal by jamming his gloved fist into its mouth. He sold the canids alive to zoos or private ranchers. Realizing that he would be the entertainment on the president’s hunt, Abernathy found an ideal spot along Deep Red Creek, in the Indian Territory. A lot of chauvinistic Texans cursed Abernathy for not holding the wolf hunt on Lone Star soil. But the carping passed. Both Burnett and Waggoner did supply Texas “daredevil” riders—their hired ranch hands with the best equestrian skills—to impress the president. Ranchers from ten or fifteen counties tried to worm a slot on the hunt party. Every man under fifty wanted to be an extra. Roosevelt spent days wolf-catching and befriending the cowboys. And he never stopped bragging on Texas.