As a teenager, I held firm to the notion that I was as American as apple pie—even though, growing up on the border, I ate apple pie once a decade or less. The closest I came to the classic dessert were the empanadas we got from the vendor who happened into Moe’s, a Mexican restaurant in El Paso’s Lower Valley. My favorite was the piña, or pineapple. It had the word “apple” in it, which made it more American. After my father forked over the change for our pastries, I would cry, “¡Joven!” (“Young man!”), like a preppy fresa from Juárez. Simon or Manny or one of the other waiters would come to the table and say, “A sus órdenes.” I would order “más eSprite, please,” then wash down my Mexican-style apple pie.

The minute we left the restaurant and headed home was when my fantasy truly began. Home was on the east side of El Paso, a majority Anglo, suburban neighborhood of homogeneous, earth-toned brick houses and xeriscaped yards. We had moved there from the Lower Valley, where Mexican Americans outnumbered Anglos ten to one and Pepto-Bismol–pink cinder-block homes and yards covered with corn and sunflowers were the norm. Our new community embodied the American sensibility I had acquired through a steady diet of eighties television and Tab cola. In my teenage imagination, my life was a Family Ties episode, and I was Alex P. Keaton’s fair-haired girlfriend. So what if I had a Mexican last name and kinky brown hair? I had no trouble pretending that my parents were Elyse and Steven Keaton, without the college degrees and fancy jobs, and that we lived in a middle-class Ohio enclave with neoclassical architecture and shade trees. Our cement patio, overlooking acres of sand and tumbleweeds, was my mudroom.

The inside of our house presented more of a challenge. While the Keatons lived among innocuous beige walls with framed artwork hung in neat rows, the walls of our home were each painted a different color—peach, powder-blue, brown, midnight-blue—and bedizened with what can best be described as Mexican-style Applebee’s decor. My mother—who, like me and her mother before her, was born and raised in El Paso—collected knickknacks. But she didn’t focus on a single theme, like owls or roosters. Instead, she hoarded a little of everything: dried flowers, miniature elephant heads, a yard-long No. 2 pencil, baskets, coffee trays, flea-market paintings, candlesticks, clocks, rolling pins, plates, artificial wreaths, tin signs, and bird’s nests, cages, and houses, all mounted to the walls. Our home disrupted my all-American fantasy, but I could live with it, as long as my mother’s Mercado Juárez taste was confined to the interior.

By contrast, I was proud of our front yard, with its non-native evergreen shrubs, imported oleander bushes, and white glitter rocks that sparkled in the sun. At its center was a five- by five-foot plot of Bermuda grass that my mother kept a rich green year-round. The yard was identical to our neighbors’ yards—a tidy, respectable garden, not embarrassing in the least.

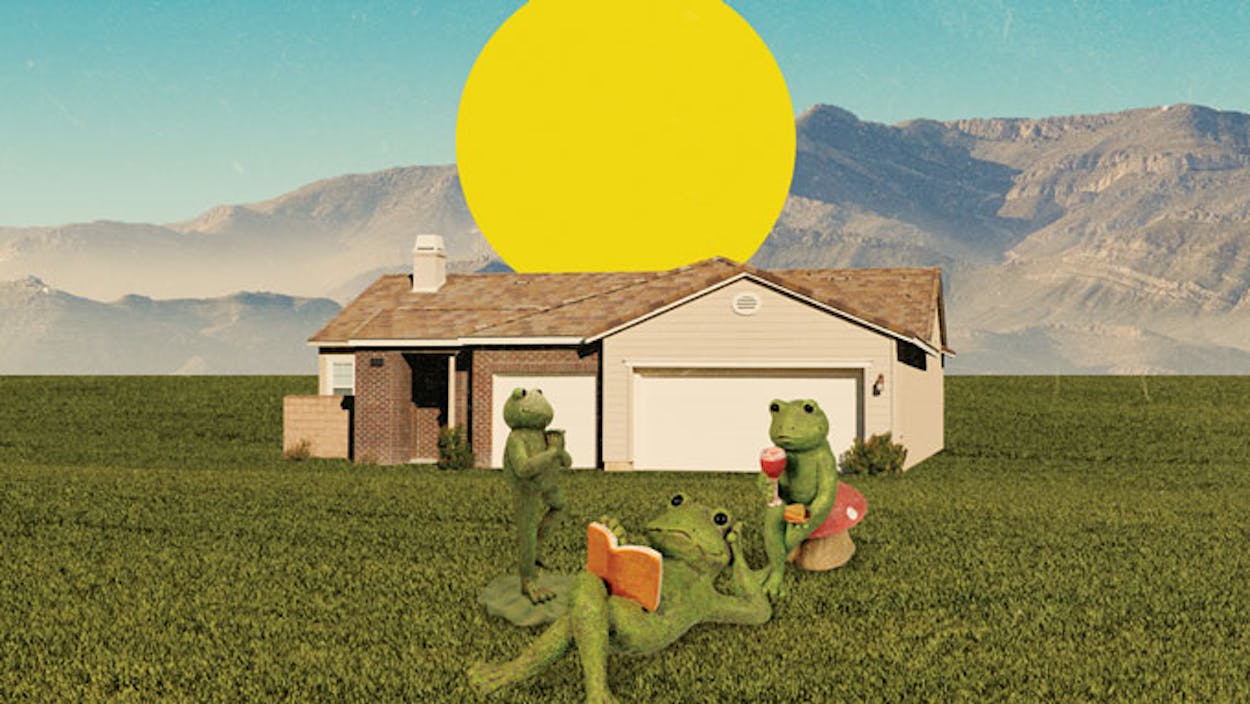

That is, until my mother decided to ruin it. One day she made a special trip to a Mexican artist’s workshop across town, near the Border Highway, and came home with three handcrafted and painted cement frog statues, which she described as “lifelike.”

“I don’t think real frogs hold umbrellas,” I said, as we unloaded them from the car.

As if she hadn’t heard me, she held up a frog that was in a reclining position, with its hands behind its head and its legs crossed, and said, “Look, this one could be your dad—this is exactly how his belly sticks out when he lies down.”

This time it was me who pretended not to hear. Then she said, “Help me put these little guys in the front yard, yah?”

I couldn’t walk away and act as though we weren’t related, like I did at the mall or the mercado, so I had to think fast. “Do you really think we should put them out here?” I said, as she arranged the ranas. “They’re so cute somebody might steal them.”

She brushed off my comment. “Don’t be silly. We left that neighborhood to come here.”

That evening I called my boyfriend, Kiki, and asked him to steal my mother’s yard art under the cover of night. The next day, as I was eating breakfast, my mother walked in and said, “The frogs are gone.” I wondered if my television-show sweetheart Alex would have committed petty larceny for me like Kiki had—no questions asked. My mother interrupted my thought.

“You were right, Chris,” she said. “I should have listened to you. There goes thirty dollars down the drain.”

My sense of triumph was dampened by the sad look on her face. I tried to cheer her up. “I’ll bet someone else is enjoying them in their own yard.”

She said, “You might be right. After I drop you off at school, I’m going to drive around the neighborhood and look for them.”

My mother spent several years scanning East Side yards for her “froggies.” I never had the heart to tell her that Kiki and an accomplice had tossed her three friends out of a pickup truck in the desert near the airport, where they met a fatal and crumbly end.

But the frogs’ disappearance didn’t keep my mother down long. A week later she decided to try again at giving our yard a face-lift. This time she would make her mark with color.

I got my first glimpse of her handiwork from the back seat of a classmate’s car as we turned onto my street. “Wow, that’s really yellow,” my friends laughed. My mother had painted our double garage doors, but it wasn’t the sun-kissed yellow of the homes in El Paso’s Kern Place neighborhood. It was highway-warning-sign yellow. It literally glowed in the dark.

I wanted to drown myself in sand. There was no way I could continue my urbane fantasy life in a house that slapped people to attention. My brothers, however, kept their senses of humor. “You can take the Mexican out of the barrio, but you can’t take the barrio out of the Mexican,” one said. The other remarked that he knew we were in trouble when our neighbor’s Mexican maid, Tencha, said, “What a beautiful color.”

I nearly bit through my retainer—fashioned for me across the river in Mexico—when I heard my father’s friend marveling at my mother’s ability to match the color of the Save ’N Gain so exactly. My mother conceded, “Well, I guess it is a little bright. Maybe you men can paint over it after work someday.” I wasn’t about to stand still while someone likened our house to a discount grocery, nor did I live my life by Mexican time. That weekend I put on a black lace headband, a Bonjour crop top, parachute pants—good for holding paintbrushes—and leg warmers, then set about making our lives less gaudy. I was finished painting by Sunday evening.

The garage doors remained white until I left for college, after which my mother painted the ribbed doors with the leftover yellow paint to make them look paneled. When I saw them, I thought the fluorescent highlights stood out in a tasteful way. Our neighborhood, I’d started to realize, was indeed devoid of color.

Now, as a mother myself, those white garage doors of my adolescence remind me of my teenage son’s room. Two years ago, I had each room of our house painted a different color, and I even mounted a typewriter to the wall. When I asked my son what color he wanted, he said, “White. Leave my walls white, Mom.” Then one day I brought home a three-foot-high wrought-iron Tyrannosaurus rex from a street vendor outside Cuero for our front yard. My son suggested I put it in the back because it might get stolen. Unlike my own mother, I listened.