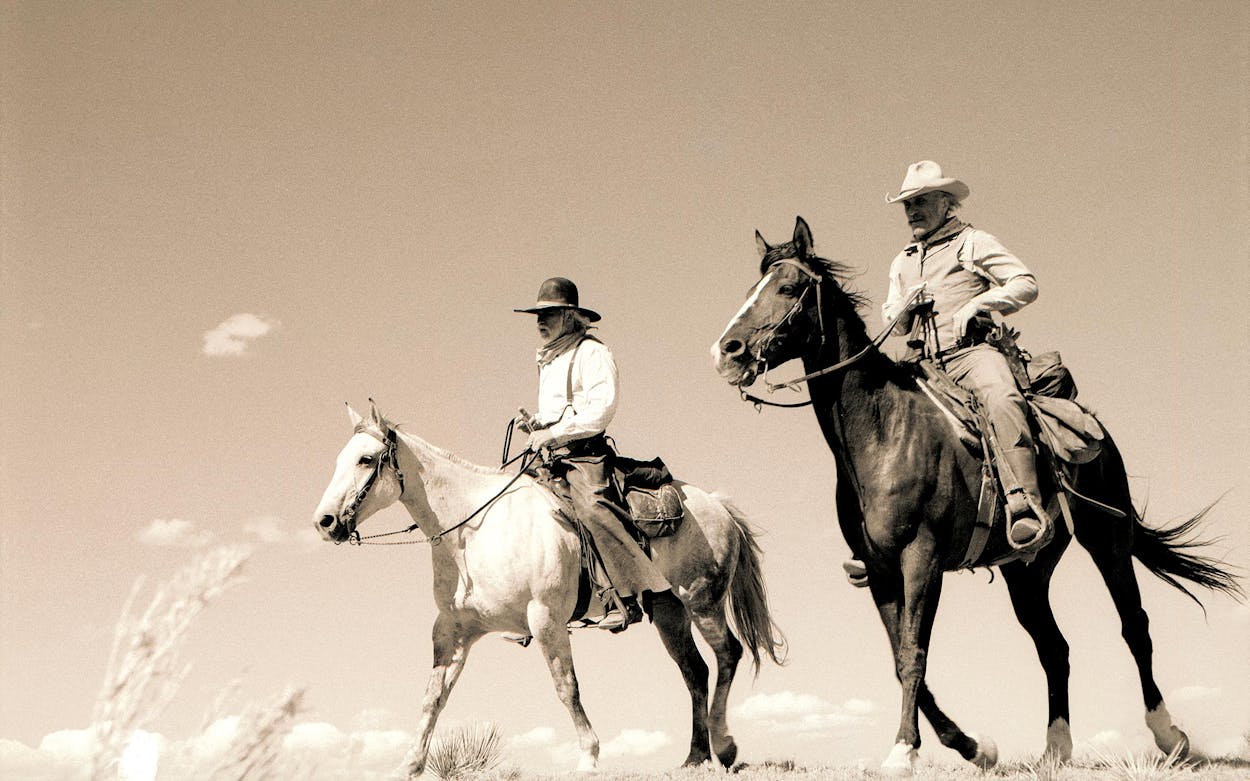

Contemplating the sweep and sprawl of Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove from the vantage of 25 years, it’s easy to forget that the story is fairly simple. Sometime in the late nineteenth century, two graying, retired Texas Ranger captains, Augustus McCrae and Woodrow Call, embark on a final adventure, their unlikely goal to push two thousand head of cattle north from the Rio Grande and become the first cattlemen in the Montana territory.

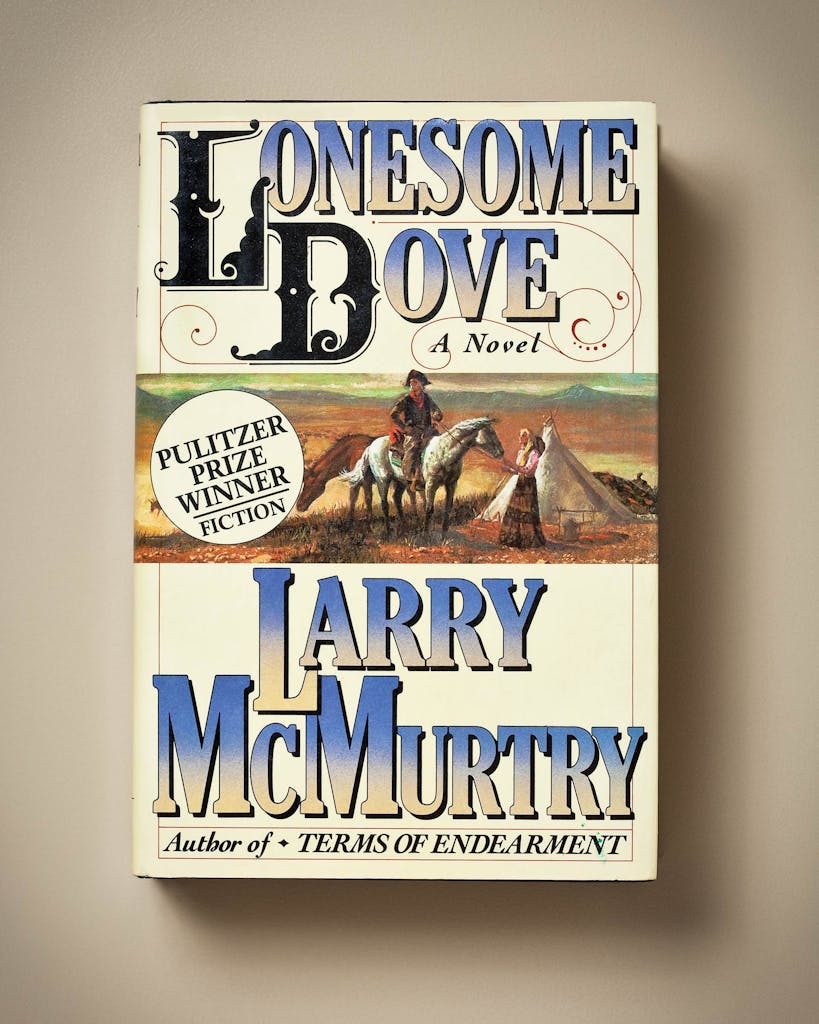

But you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone who would describe Lonesome Dove so modestly. It is the great hero myth of Texas, the state’s favorite depiction of itself and the world’s favorite depiction of Texas. Since its publication, on June 13, 1985, more than 2.5 million copies have been printed in the United States; the 1989 miniseries, which is the way most fans first came to the story, is the best-selling western DVD of all time. But the better measure of Lonesome Dove’s import is anecdotal. If you know a Texan named Gus under the age of twenty, odds are he was named after McCrae. I know two such kids—and one is a girl.

To some, Lonesome Dove is a novel, the achievement that turned McMurtry—an author of moderately read books that had been made into great movies—into one of the most popular and respected writers of the twentieth century. To others, it’s Austin screenwriter Bill Wittliff’s miniseries, the finest western film ever produced. Some would describe it as an epic journey of distinctly American ambition; others consider it a universal depiction of loyalty between friends. One fan will say the story belongs to the endlessly charming Gus, that everything you need to know about living and loving is contained in his portrait. Another will argue that it’s the story of ramrod Woodrow Call, a man who abided by the code of the time, who refused to allow himself to feel and wound up alone. The wildly varied interpretations point to the fundamental contradiction at the heart of Lonesome Dove, the thing that distinguishes it from pure entertainment. It’s at once a celebration and a critique of the myth of the Texas cowboy, a reflection of McMurtry’s lifelong ambivalence about the people and the place that shaped him.

It’s a story that makes such an impression that you remember not only its substance but where you were when you first took it in. I read Lonesome Dove in 1989, through the weeks that followed my college graduation. When I picked it up again this spring, I was taken back in time, not to the Old West but to an inflatable pool in a front yard in Waco—and the sense of limitless possibilities I recalled weren’t Gus’s and Call’s but my own. Then, as I watched these familiar characters go about their living and dying, I remembered why I loved the book: It’s the best depiction of a friendship that I’ve ever read, an 843-page expansion on a comment Dizzy Gillespie made after his friend Charlie Parker died: “He was the other half of my heartbeat.”

To compile this oral history, Texas Monthly talked to people involved in the creation of the book and the miniseries, as well as to critics and scholars. (And please note: This piece is largely directed at those who already know the story. There are many spoilers ahead.) Wittliff’s archive of the miniseries’ production is housed at Texas State University, in San Marcos, and staffers there used a mailing list of Lonesome Dove lovers to solicit testimonials. Responses came in from around Texas, the U.S., Canada, and Australia. Some were cute—people had crafted poems, songs, Gus and Call action figures, and a backyard replica of the Hat Creek Cattle Company’s border bunkhouse. One man said his daughters’ suitors had to watch the miniseries before they could be accepted into the family. Other revelations ran deeper. A woman described finding refuge in the book over the eight months she spent caring for her dying mother. A family watched it on a hospital VCR during the weekend their patriarch died.

Lonesome Dove is not a place these people go to escape. They turn to it for definition, for heroes who look and talk like them, who address life in a way they wish they could. Few books or films manage to do that for an entire culture, and none has done it for Texas to the extent of Lonesome Dove. It’s our Gone With the Wind. It’s the way we want to see ourselves.

Overture

The novel is lengthy by any standard, populated by a dizzying array of major and minor characters, each of whom requires an investment of time to get to know and keep straight. And though it can accurately be described as a cattle-drive book, Larry McMurtry spends a very leisurely 250 pages getting around to the drive itself. Still, while many fans identify Lonesome Dove as the longest book they’ve ever read, they also say that they raced through it—and that it’s one of the few books they’ve reread.

Tommy Lee Jones portrayed Woodrow Call in the miniseries. Lonesome Dove is a mosaic of jokes, legends, superstitions, and real people, all of it coming together in a fascinating narrative. The language sounds like it’s coming from my country. Halfway through I realized I wasn’t going to want it to end, so I would only read maybe fifty pages a day.

Robert Duvall portrayed Augustus “Gus” McCrae. I read it in ten days. And later I named a horse Woodrow.

Peter Bogdanovich directed and co-wrote, with Larry McMurtry, the film adaptation of The Last Picture Show. I read it in one week and thought it was brilliant. I felt it was written almost in vengeance to show that novels can do anything better than a movie.

Mary Slack Webb is the owner of the Lonesome Dove Inn, in Archer City, and a childhood friend of McMurtry’s. Larry would send copies of his new books to my mom, and I remember when we got Lonesome Dove. It was summertime. I started it at six a.m. and turned the last page at six a.m. the next day.

Leon Wieseltier is the literary editor of the New Republic. I’ve got two copies, one that Larry inscribed and a Hebrew translation. It’s about the least Jewish book I could ever imagine. But in Hebrew it’s also impossible to put down.

Barry Corbin portrayed Sheriff July Johnson’s deputy, Roscoe Brown. Go to any ranch in the country and there’s two things you’ll see consistently. One is a copy of Elmer Kelton’s The Time It Never Rained. The other is a DVD or a VHS of Lonesome Dove, usually worn-out and usually about the fourth or fifth copy they’ve owned.

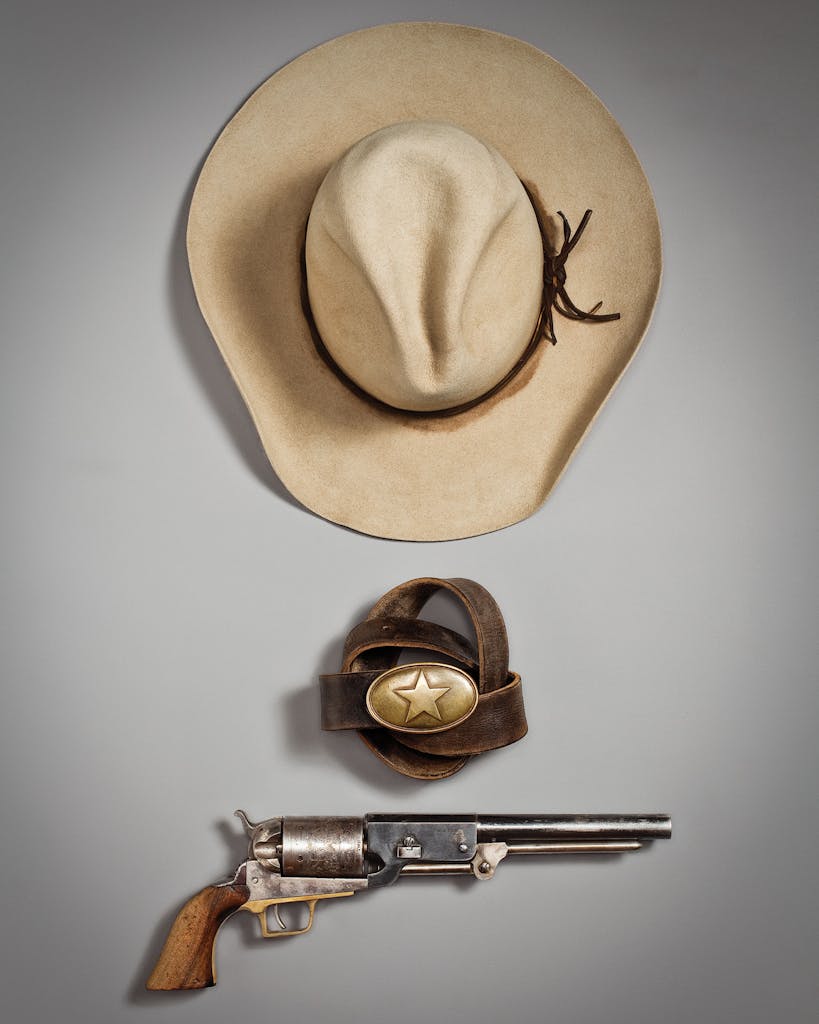

Steven Davis is the assistant curator at Texas State’s Southwestern Writers Collection, the home of Bill Wittliff’s Lonesome Dove archive, which includes an exhibit featuring numerous props from the film. The exhibit draws people from all over the world, and when they see the prop of Gus’s dead body, it makes some of them weep all over again. I’ve seen people drop to their knees and pray.

Larry McMurtry is the author of Lonesome Dove. You know . . . it’s just a book. The fact that people connect with it and make a fetish out of it is something I prefer to ignore. I haven’t held Lonesome Dove in my hands or read it in years. I just don’t think much about my books, particularly not ones that go back 25 years.

The Book

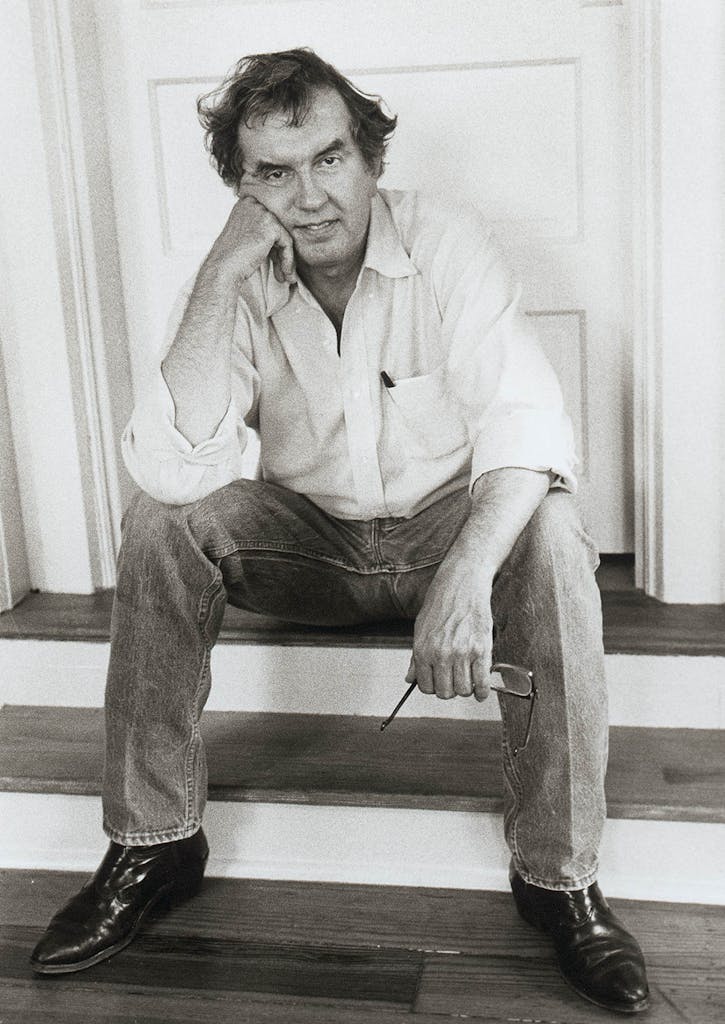

McMurtry was born in Wichita Falls in 1936 to a family who had worked cattle and horses in the area since 1877, when his grandparents arrived from Missouri. He grew up on the family ranch outside Archer City and worked it as a teen but eventually declined to continue in the McMurtry cattleman tradition. He’d already been seized by books, the passion that would come to define him. After high school he fled ranching and Archer City—which he once famously referred to as a “bookless town, in a bookless part of the state”—for the singular paradise of a university library. He eventually earned a bachelor’s degree in English from North Texas State University (now the University of North Texas), in Denton, and a master’s from Rice University.

Dave Hickey is an art critic, a professor of art practice at the University of New Mexico, and a longtime friend of McMurtry’s. Larry is a writer, and it’s kind of like being a critter. If you leave a cow alone, he’ll eat grass. If you leave Larry alone, he’ll write books. When he’s in public, he may say hello and goodbye, but otherwise he is just resting, getting ready to go write.

Michael Korda is McMurtry’s longtime editor at Simon & Schuster. Writing is like breathing for him. He gets up every morning and stacks a bunch of yellow paper next to his typewriter, and from then until breakfast he types. If you stay down at the ranch, you hear him doing it because he uses that old-fashioned typewriter that goes duh-duh-duh-DING! Just typing away. That’s what he does.

Dave Hickey We’re close in age, but he grew up in an older world, out in the country. I stayed at his house in Archer City once for a month or two and began to understand what living in the country means: It’s sitting in a little bitty restaurant, looking out the window at a cow, but you only have powdered creamer for your coffee.

George Getschow is an assistant professor of journalism at the University of North Texas. When he was a kid, he would walk from the family homeplace on Idiot Ridge to this little red barn a few hundred yards away, climb to the loft, and read. He said that if the cowboys caught him with a book, they’d tell him to take off his spurs and check himself into the nervous hospital.

Gregory Curtis was the editor of Texas Monthly from 1981 to 2000. Larry’s probably read ten times more than anyone I know. I took a fiction-writing course from him when I was a senior at Rice, in the late sixties. He distributed long reading lists, mostly contemporary books and authors that I had never heard of. But there were also literary westerns like The Ox-Bow Incident, by Walter Van Tilburg Clark, and cowboy memoirs like We Pointed Them North, by Teddy Blue Abbott. I’d never heard of them either.

Leon Wieseltier Larry is an uncommonly disabused man. I remember once we were having dinner at Nora’s in Washington, and he was telling me about some famous fight Kit Carson had with a great Indian chief. He said that according to legend they waded into a creek and fought hand-to-hand until Kit Carson valiantly overcame his opponent. Larry said, “Well, the truth isn’t that. The truth is that Kit Carson waited for the Indian to show up and shot him in the back.” Then Larry paused and said, “Which is exactly what he should have done.” I thought, “Oh, so that is who my friend is.” The very antithesis of the awful Liberty Valance rule: He prefers printing the truth to printing the legend. He’s a born demythologizer. But he stays with the places and the people that he has unsentimentally demythologized. He doesn’t do it out of contempt.

McMurtry was 25 when his first novel came out, 1961’s Horseman, Pass By, and he followed with two more by the end of the decade, Leaving Cheyenne (1963) and The Last Picture Show (1966). They became known as the Thalia trilogy for their shared setting—the fictional small town of Thalia, a thinly veiled Archer City—and their exploration of the collision of urban modernity and old, rural Texas.

Hollywood adapted two of those books into Oscar-nominated movies, 1963’s Hud (Horseman, renamed) and 1971’s The Last Picture Show. In 1972 his Picture Show collaborator, Peter Bogdanovich, convinced Warner Bros. to pay the two of them to work on a western. The film was never made, but it planted the seeds of McMurtry’s opus.

Peter Bogdanovich Cybill Shepherd [Bogdanovich’s girlfriend at the time] was shooting Heartbreak Kid in Miami Beach, and Larry and I decided to meet there to discuss the picture. I will never forget the incongruity of Larry and me sitting on a balcony at the Fontainebleau, overlooking the Olympic-size swimming pool where Cybill is doing laps, and Larry saying to me, “So what kind of western do you want to make?”

So I told him. I wanted John Wayne, Jimmy Stewart, Henry Fonda, Cybill, the Clancy Brothers [an Irish folk group], and so on. I said it needed to be a trek: They start somewhere, they go somewhere. We didn’t want to do cattle because that was Red River. Larry suggested horses. Fine. And he said we might as well start at the Rio Grande and go north.

We started talking about the characters. Larry said they could have a pig farm, that that would be funny. I said, “Yeah, Duke Wayne and Jimmy Stewart with a pig farm would be funny.” Then we discussed who Fonda would be. Fonda always had a slightly ambiguous quality, so he became the slick one, the one you wondered, was he a good guy or a bad guy. Jimmy was the character most connected with the land. We named him Augustus, because we liked the way Jimmy Stewart would say, “Augush-tush.” And Wayne’s character was always in charge. But we sent him up quite a bit.

Stephen Harrigan is an Austin novelist, screenwriter, and essayist. In McMurtry’s script these guys are tramps, stalled out completely, just gabbing on the porch.

Peter Bogdanovich I wanted the Clancy Brothers because [director] John Ford had told me his uncles had come from Ireland to fight in the Civil War, and when I’d asked which side, he said, “Either side!” I liked that.

Stephen Harrigan Fonda’s character, who becomes Jake Spoon, had a much bigger part. And Gus dies when he’s trying to tame a horse. He doesn’t get killed by Indians. So you don’t have the Call character bringing his body back.

Larry McMurtry This was a different story. This wasn’t a trail-driving story.

Peter Bogdanovich Larry went home, and I went back to Los Angeles, and he would send me pages that I rewrote or cut down. We tried a lot of different titles, “The Brazos,” “The Compadres.” The one we settled on was “Streets of Laredo.”

Larry McMurtry The draft was welcomed by the studio, but not the three actors. This was a story about aging men. Eventually Stewart and Fonda came around because they weren’t working that much. Wayne was working right up until he dropped, but he didn’t like it, and he wouldn’t do it.

Don Graham is a professor of English at the University of Texas at Austin. John Wayne wasn’t going to lend himself to a total critique of the genre he had been working in for forty years. He wasn’t going to make Blazing Saddles.

Peter Bogdanovich It was definitely about the end of that era. One of the first things Jimmy’s character goes into is how long it takes to pee when you’re older. And there was an extraordinary scene where they ride into a town and go into a bar with pictures of cowboys all over the place but none of them. So they go in the back room looking for one because they know it used to be there. They go through all of these pictures and finally find it. The sequence ended with a close-up of the photo. It was very touching.

By then McMurtry was living in Washington, D.C., which put him in a kind of cultural limbo. He’d already figured out that he was too sophisticated for small-town Texas, and now he was learning, according to his editor, Michael Korda, that he was too country for the city. He opened a bookshop in D.C., where he could concentrate on reading, writing, and collecting. He continued to type each morning—screenplays, essays, book reviews, and fiction. The people in his novels remained contemporary, but he moved them out of the country, first to big-city Houston—the setting for 1975’s Terms of Endearment, considered by many to be his best book—then out of Texas entirely.

Michael Korda I’d met Larry when he was looking for a publisher for Moving On [published in 1970]. It had all the makings of the Great American Novel—except that it was about rodeo. Our sales department loved it so much they had buttons made reading “I’m a Patsy,” after the heroine. However, it just wasn’t the huge success we hoped it would be. After that, I would tell the sales reps at every meeting that one of these days Larry would write the Great American Novel, and it would be a huge success.

Leon Wieseltier Larry was respected but not well understood. People in New York have extremely narrow horizons. The parochialism of the center is always greater than that of the provinces. In the provinces, they keep an eye on the center, but in the center they just gaze lovingly at themselves with both eyes.

Nicholas Lemann is the dean of Columbia University’s journalism school, a New Yorker staff writer, and a TEXAS MONTHLY contributing editor. Larry was considered the most important Texas writer, but at the same time he was also the bad boy of Texas letters. In a Narrow Grave [McMurtry’s 1968 essay collection] semi made fun of such sacred figures as Frank Dobie, which you were never supposed to do.

Bill Wittliff is an Austin writer and photographer who adapted Lonesome Dove for television. My wife, Sally, and I started Encino Press in Austin in the sixties, and we published In a Narrow Grave, which had all these four-letter words. And it jumped some of the Texas heroes, some of my heroes. Ooh, man, once or twice a week somebody called my office and chewed my ass out.

Don Graham Then in 1981 McMurtry wrote this famous piece for the Texas Observer, “Ever a Bridegroom,” in which he went back and machine-gunned everybody he hadn’t taken out in Narrow Grave. It was like the Germans in World War II retracing the field for anyone still living. He went through the whole catalog of Texas writers and said they were too sentimental and romantic, that they should stop writing about the past. Meanwhile, he holes up somewhere and writes Lonesome Dove, which made his fortune.

Nicholas Lemann He declared that the big topic for writers in Texas was urban Texas, which really offended the Texas literary establishment. They believed that Texas was fundamentally rural and real Texas literature had to be rural literature. Then suddenly he writes a book about a cattle drive that is unmistakably McMurtrian but, nonetheless, treats the cowboys as heroes.

Larry McMurtry You don’t have to be consistent. What I feel when I write discursively and when I write fiction are just different. For an essay you have to think from sentence to sentence and make one follow another. Fiction is less conscious. It’s a trancelike experience for me. I see the characters, listen to what they say, and write it down.

Dave Hickey When I saw Lonesome Dove coming out, I thought, “Oh, shit, he’s finally doing what everybody wants him to—he’s writing a cowboy book.” And I understood that. I’d had all these professors from Harvard in graduate school, and they didn’t want to know what I really knew, which was how to behave at a debutante party in Fort Worth. They wanted to know about cowboys.

Larry McMurtry I had done all the contemporary material I knew anything about. I had no place to go but back in time. I suppose it is a historical novel, but I didn’t go outside my family memory. Our ranching experience goes back to the 1870’s. I had nine ranching uncles, the oldest of whom were trail drivers, and I heard them talk about it when I was a little boy.

Don Graham I think part of the reason he wrote Lonesome Dove—and I have never heard him or anyone say it—was that he had a good idea of the market. Texas was coming up on its sesquicentennial, and [James] Michener had been selected by the governor to come down to write Texas and tell us about ourselves. I think McMurtry wanted to say, “I’m here. I know this past better than any Pennsylvania-Dutch Yankee does.”

Larry McMurtry That’s stupid. That didn’t have anything to do with the creation of Lonesome Dove. The script had languished for twelve years before I finally realized they didn’t want to do it. So I bought it back for $35,000. Then I picked it up and laid it back down three times. I started it and stopped to write Cadillac Jack [1982], and then again to write Desert Rose [1983], and then I left it for another year or two. I didn’t have a title.

One night I was having dinner at the famous steakhouse in Ponder, about ten miles west of Denton, and I saw this old church bus with “Lonesome Dove” written on its side and knew that was it. I went home and finished the book. I already had about 350 pages, so it didn’t take long. A few months.

Working at his standard pace of 10 typed pages a day, he produced a 1,600-page manuscript and delivered it to Simon & Schuster in late 1984. On its surface it was the story of a cattle drive, based loosely—and, in parts, closely—on the real lives of Texas trail drivers Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving. But the book had a greater ambition. It was written in the style of a Victorian novel, with dozens of characters to fall in love with or detest and sharp social commentary—in this case on the ethos and mythos of the American West. Korda quickly informed the sales reps that this was the epic they’d been waiting for.

Larry McMurtry It all comes out of Don Quixote. It is the visionary and the practical man. Gus and Call. That is the only thing that is the same as the original script, these two characters, these archetypes.

Carolyn See is a Washington Post book critic and UCLA English professor who teaches Lonesome Dove. Gus is about affection as much as achievement. He is immensely lovable, performing meaningless acts of gallantry just to watch himself being darling. And Call is such a pain in the ass. He’s just awful. But that’s why it’s an American story. If we didn’t have the Captain Calls, we wouldn’t have skyscrapers or the Golden Gate Bridge or the Pentagon.

Mark Busby is the director of the Southwest Regional Humanities Center at Texas State. Call is a figure lacking some redeeming qualities. There’s the way he treats his son, the way he’s incapable of sustaining a relationship with another human being except for Gus. Yet people don’t see those as flaws. They think the strength of his character overrides that.

Larry McMurtry Why won’t Captain Call acknowledge his son? You know, that has puzzled me as much as it puzzles readers. I don’t know. I kept expecting him to, and then he didn’t, except to give Newt his horse.

Richard Slotkin is a professor emeritus of English and American studies at Wesleyan University and the author of an award-winning trilogy on the myth of the American West. They go to Montana because they understand themselves as heroes, men of a certain function in the world. The frontier is closed in Texas. Their function has passed. So they make a new frontier.

Stephen Harrigan They are two deeply flawed men who desperately need each other. Gus and Call are like Holmes and Watson, or Captain Kirk and Mr. Spock, two halves of a single personality. Call’s emotional limitations are at the heart of the book. Gus’s grandness and acceptance of life are what keep you reading, but it’s Call’s story. It’s the story of a guy who missed out on life.

Don Graham The book is kind of like a buddy movie, which is a constant in American literature, going all the way back to James Fenimore Cooper. They’re close friends on a grand adventure. They know the West is over, and they are doing this as a last hurrah.

Larry McMurtry The Goodnight-Loving relationship is echoed, but it’s just echoes. I did copy the words Goodnight put on Bose Ikard’s monument in Weatherford [Ikard was the model for the book’s black scout and cowhand, Deets]. And I knew vaguely that I was paralleling part of Teddy Blue Abbott. But I’m not thinking about that when I’m writing.

Leon Wieseltier There are so many novels now in which you can smell the research. Gore Vidal once said that when he was writing his novel about Lincoln, he would read the historians at night and write that chapter in the morning. It was all a quick study. But with Larry, you feel that he had all the history, geography, and mythology already in him, that he possessed his subject and didn’t have to work it up.

Richard Slotkin The myth of the West is an idealized version of American history. The Fenimore Cooper version is white people against Indians, the uncivilized. But it’s also these same white people against “dudes,” the Eastern bankers who are too white, too civilized. The true American lives on the frontier, on the border between these two worlds.

Fenimore Cooper could tell that story. He lived on the frontier, moved to the city, and wrote what he remembered, like a lot of nineteenth-century writers. By the time you get to the era of movies, that’s getting thin. And by the great period of Western movies, the fifties and sixties, you’re not dealing with people who know the real West at all. It’s myth based on myth at that point.

Leon Wieseltier One of the first things I learned from Larry was the extent to which what we think of as the West is what Hollywood taught us to think of as the West—and how very early Hollywood did that. Lonesome Dove was a kind of response, a way of restoring the actual experience. Ideals without idealization: That’s Larry. If bad things can happen, they do.

Dave Hickey Larry has something that my grandfather had, which is a ruthless view of nature. I remember watching a sunset with my grandfather as a kid. I said, “Isn’t that beautiful?” He said, “Oh, yeah. And while you’re admiring nature, nature is looking back at you, saying, ‘Yum, yum, here comes dinner.’” There is in Larry an idea of nature as this monstrous force in which we make our way very fragilely. Lonesome Dove is very good about this.

Larry McMurtry The book is permeated with criticism of the West from start to finish. Call’s violence, for example. But people are nostalgic for the Old West, even though it was actually a terrible culture. Not nice. Exterminated the Indians. Ruined the landscape. By 1884 the plains were already overgrazed. We killed the right animal, the buffalo, and brought in the wrong animal, wetland cattle. And it didn’t work. The cattle business was never a good business. Thousands went broke.

Nicholas Lemann By being as realistic as he was about cattle drives and people and their lives, by de-John Wayne-izing the West, he actually made the myth appealing for a new age.

Don Graham The Godfather was supposed to demythologize the mob, too, but we all wanted to be gangsters after we saw it, right?

When Lonesome Dove hit bookstores, in June 1985, the reaction was universally glowing. The Los Angeles Times called it “McMurtry’s loftiest novel, a wondrous work.” Writing for the New York Times Book Review, Lemann dubbed it “the Great Cowboy Novel.” The book spent 24 weeks on the hardcover best-seller list and then 28 weeks more on the paperback side. It also changed the way the world viewed McMurtry. In April 1986 Lonesome Dove won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, and three years later he was elected president of the PEN American Center, the prestigious literary organization whose past presidents included Norman Mailer and Susan Sontag. McMurtry was the first non-New Yorker to head PEN since 1922.

Don Graham That same year, 1985, Cormac McCarthy published Blood Meridian. It sold about 1,200 copies. Michener’s Texas sold well, but McMurtry’s book immediately became the favorite of all sentient Texans. I was going out to L.A. a lot at that time to work on a book about Audie Murphy, and every time I got on a goddam airplane, it was littered with copies. Everywhere you looked, there was Lonesome Dove.

Michael Korda The reviewers were beginning to feel a degree of guilt over the way they had reviewed Larry in the past. That was doubled by the dawning recognition that with his bookshop he was involved in the cause of books, and even if he did grow up in Archer City, he was a bona fide intellectual and literary person. But the only thing that mattered was that Lonesome Dove is a terrific book.

Leon Wieseltier It’s one of those books that crushes the distinction between high literature and popular fiction, the way Dickens did. I mean, Dickens was high and Dickens was low: He serialized great art. Lonesome Dove shows that a sophisticated writer can move millions of people.

Don Graham There’s a reputation to be made among intelligent readers, and McMurtry has that readership. He has it in Australia, Europe, England, here. But he doesn’t have it in the academy, where Lonesome Dove doesn’t count as “literature.” It doesn’t have the rhetorical flourishes that English professors want. That’s a crude statement, but I don’t ever hear anybody in the academy talking about Lonesome Dove, whereas McCarthy’s Blood Meridian has got a small library of scholarly exegesis and analysis.

Dave Hickey Professors ignore Larry because you can’t teach seamless talent. He does what Henry James did; all the ideas and commentary are subsumed in the narrative, and trying to teach that would be like using Stevie Wonder to teach songwriting. What you learn is that he can do it and you can’t.

McCarthy’s writing, on the other hand, is house-proud. It’s this collage of antique and modern prose, chock-full of tropes and maneuvers—pure professor bait. They’re also drawn to his unrelenting pessimism. He has this little tic characteristic of abused children—whenever we’re having a good time, somebody is about to get shot. You’re sitting around having a nice conversation in the Dairy Queen, and then you go outside and get mowed down by gunfire. There’s a Calvinist rhythm to that, and a vision of the omniscience of evil that is so profound as to encourage complacency. If we’re all going to be shot after we have a good meal, why bother? In No Country for Old Men, the Mexican mafia are totally omniscient; they know when you’re at the bus station. That’s not good storytelling.

But Larry has what Dickens had: No matter how horrible what’s happening in the narrative is, there’s a little bubble of laughter underneath that’s all about how much fun it is to write. The words never quite touch the page. There’s this sort of ludic energy—thank you—this joyful propulsion that drives the prose along.

Leon Wieseltier When Larry won the Pulitzer, people sat up and paid attention. There is a certain kind of Manhattan literary snob who cares about status. You may have heard that about Manhattan.

Larry McMurtry Well, that didn’t have as much effect on me as people might think. It’s a journalist’s prize. I was glad to get it, I guess, but I was busy and didn’t go to the ceremony.

I’d rather be considered a man of letters, functioning over fifty years, than be known as the author of one book.

The Miniseries

For all the reverence accorded McMurtry’s masterpiece, when the names Gus and Call come up, most people don’t picture McMurtry’s descriptions but the faces of Robert Duvall and Tommy Lee Jones. That can’t be chalked up simply to the monstrous disparity between the number of people who watch TV and the number of people who read books. Duvall and Jones seemed to live in the roles, growing them from the characters that McMurtry imagined and Wittliff adapted into something of their own. Jones plays Call a little warmer than he is depicted in the book. He’s no more able than McMurtry’s Call to acknowledge his pride in Newt’s maturation or the pleasure he takes in Gus’s friendship, but when Jones is on the screen, you see those feelings on his face. Similarly, Duvall’s Gus has a slightly harder edge; it’s less of a surprise when he beats down the San Antonio bartender. And the gestures, the walk, and the glint in his eye when he asks the prostitute Lorena for “a poke” all belong to Duvall.

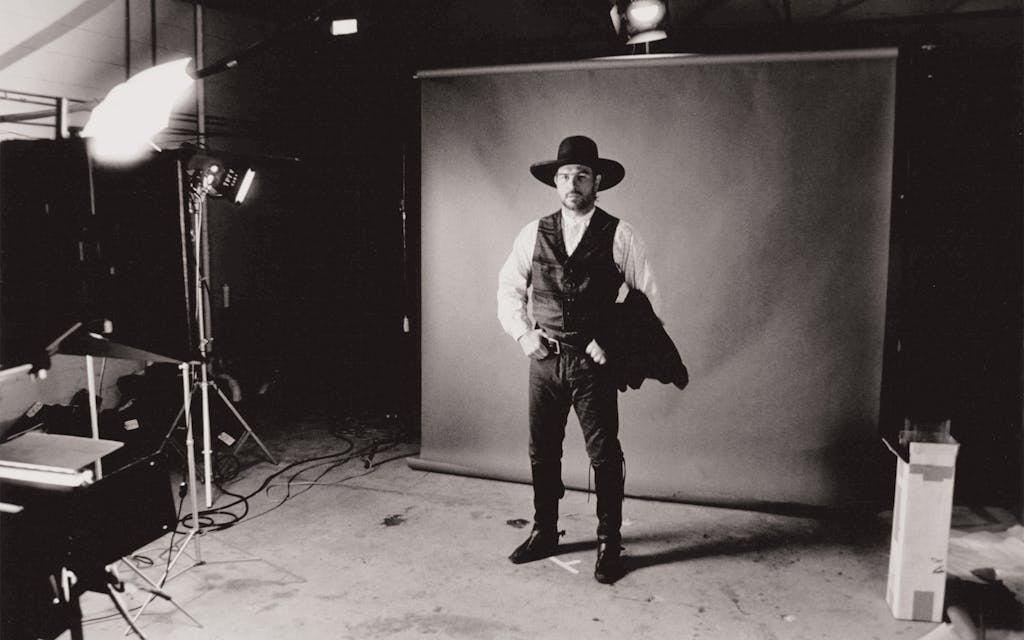

Oddly enough, close readers of the book were skeptical when the two were cast. Physically, Duvall looked more like the book’s description of Call, four inches shorter and grayer than Gus. Jones in costume didn’t look like either of them so much as he did pop-country singer Kenny Rogers. That may be one reason McMurtry says he’s never seen the miniseries in its entirety; he has a different picture in his mind for every character. Or maybe it’s because of the grand musical score and romantic cinematography—if McMurtry was nonplussed by his readers’ rush to find heroes in his book, he must have been put off by the elements in the miniseries that were calculated to make that very thing happen.

But the miniseries proves that though television has a lower common denominator than literature, that doesn’t preclude it from occasionally qualifying as art. Wittliff insists that whatever greatness the miniseries achieved is due to its fidelity to the source material. There’s a truth to that, but Wittliff’s love of the story and characters shows up on the screen just as surely as McMurtry’s love of writing shows up on the page.

Wittliff wasn’t even the first choice for the job. Suzanne de Passe, the head of Motown Records’ TV-and-film division, optioned the movie rights to the book before it was published. But she spent the next two years trying to find a way to make it a feature film; at one point legendary director John Huston was considering it. But no one could figure out how to keep the story intact at feature-film length. So she decided on the miniseries format and contacted Wittliff. He’d adapted a variety of works into films, from Walter Farley’s The Black Stallion to the Willie Nelson record Red Headed Stranger. He was from Texas and knew McMurtry.

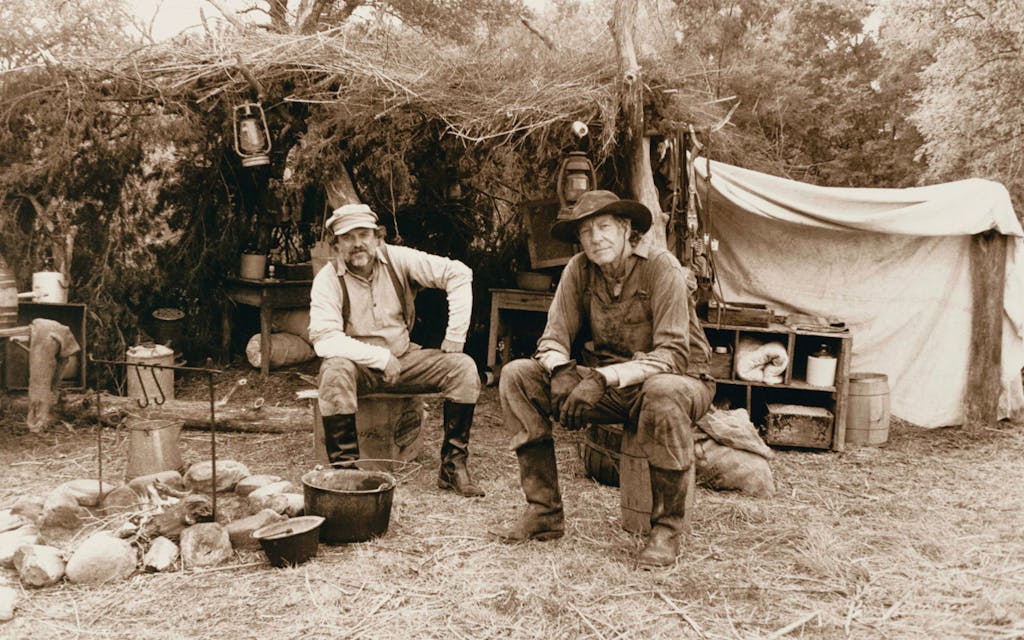

He got the job in late 1986 and spent the next year writing the script. When he finished, de Passe secured $16 million from CBS and $4.5 million from another backer. She and Wittliff would be executive producers. The first three months of 1988 were then spent in preproduction, scouting locations and assembling a creative team, all the while balancing their budget constraints and Wittliff’s insistence on absolute authenticity. The key behind-the-scenes hires seemed counterintuitive for an American western: Producer Dyson Lovell was from Zimbabwe; director Simon Wincer, best known for the feature film Phar Lap, a heart-tugger about a doomed racehorse, was from Australia; and cinematographer Doug Milsome, a veteran of Stanley Kubrick films, was from England.

Bill Wittliff There are so many reasons this thing should not have gotten made. At that time, there was nothing deader than the western, except the miniseries. And this was both.

Suzanne had somebody read the book on tape for me. Sally and I have a place at South Padre that’s essentially six hours from Austin. I’d plug one of those tapes in my pickup and head down to Padre. Driving through South Texas, listening to Lonesome Dove, I could see everything the guy was reading. Then I’d get there and write.

I did make some changes. In the novel, Gus tells Newt that Call is his father when they’re burying Deets. But I thought, emotionally, you don’t want to share those two events in the same scene. So I moved it to the fight with Dixon, the Army scout. And I cut Wilbarger, the cattleman who comes early to Lonesome Dove to buy horses. Later he’s killed by the Suggs brothers, and God, his death is fabulous. But it falls on top of Jake’s. I felt they would’ve sucked energy from each other.

Tommy Lee Jones I was highly amused when Bill told me that an executive had called from New York and asked, “Do we have to use cows?”

Bill Wittliff CBS calls and says, “We’ve got troubles. Can you fly out here?” I arrive, and they tell me it’s the cattle. The cattle cost too much money. But one of their guys has an idea. He says, “Bill, listen to this. What if they start that drive and right away there’s that storm and the cattle get scattered? You’re the writer; why not let the cows go and have Call say, ‘Let’s just keep going.’ Then you have all those guys going to Montana, doing all that stuff, but we don’t have to pay for the cattle.” I said, “Or here’s a thought: Why don’t we just forget the cattle and get a herd of Angora goats? They can be the first guys to drive a herd of goats to Montana.” One of the execs snapped and said, “Yeah, goats!” I said, “No, that’s a joke.”

Simon Wincer was the director of Lonesome Dove. Every director in America wanted that job. I felt half of Texas was looking over my shoulder at this Australian proposing to film “our bible.”

Bill Wittliff CBS was excited about Simon’s new film, The Lighthorsemen [about an Australian cavalry unit fighting the Turks in World War I], so they flew him and the movie to Santa Fe, where Dyson, Suzanne, and I were scouting locations. I watched it and thought it was beautifully filmed, but it was also on a huge screen. We were going to be in a little box. So he went back to Australia, and I thought about it for a week and decided Simon was not the guy. Then he came to Austin, and I took him to the country club for dinner.

Simon Wincer I ordered a prawn cocktail and Bill ordered oysters on the shell, and when they arrived, he cracked open the first oyster, and sitting in the middle was a pearl. He looked up at me and he said, “I think this is a sign.”

Bill Wittliff Right as I’m opening my mouth to say, “I can’t do this,” I saw that pearl. Now, I’m spooky anyway. I told CBS okay.

Doug Milsome was the cinematographer. I think having an Englishman on camera and an Australian as director gave it a certain flavor of seeing the West for the first time, rather like Gus and Call, who were seeing this part of America for the first time.

Cary White was the Austin-based production designer. Simon didn’t know beans about the American West. And one producer was this intellectual from Africa, Dyson, and another was Miss Motown. So Wittliff was the only one who knew his stuff.

The producers worked with casting director Lynn Kressel to find the right actors. Among those who didn’t make the cut were Kevin Spacey, who read for July Johnson, and Uma Thurman and Julia Roberts, who both tried out for Lorena. Improbable names came up too. Andy Griffith was considered for one of the leads. And initially Duvall was recruited to play Call.

Robert Duvall My ex-wife at the time said she’d read a book she liked better than Dostoyevsky, Lonesome Dove, and that the part for me was Augustus McCrae. But they’d already offered Gus to James Garner. I said, “If you can get him to switch parts, I’ll be in this.”

Tommy Lee Jones It became clear that Jim Garner wasn’t physically up to it. So Bobby got the part he’s more suited for, leaving me an opening to insinuate myself into the cast. I wanted a job on that movie and pursued it arduously.

Dyson Lovell was the producer. Next I went after Anjelica [Huston]. I’d known her since she was a teenager, because she’d auditioned for me in London when we did Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet. Then I got a call from the network. “Listen, we want to remind you this is CBS, not PBS. We want somebody with some TVQ [an industry measure of a performer’s appeal to television audiences].” That’s when Robert Urich [who played Jake Spoon] entered the equation, and Ricky Schroder. Ricky had done Silver Spoons, but I knew him because I’d found him his first job, The Champ. I had a bit of a surprise from my colleagues at the suggestion.

Ricky Schroder portrayed Newt Dobbs. I actually declined the role at first. I wasn’t a great horseman. And I had a pretty severe childhood allergy to them. Then CBS called and said, “We’ll clean the horse every day. You’ll have the cleanest horse ever. We’ll get you whatever medicine you need.”

Lynn Kressel was the casting director. I love being able to cast unknowns in supporting roles, like Chris Cooper [who played July Johnson] and Steve Buscemi [Luke]. D. B. Sweeney was a bigger name than them, and he got cast early as Dish. Brad Pitt read shortly after that, and I thought, “Oh, shit, Dish would have been his role.”

Danny Glover portrayed Joshua Deets. I read the book. It was sweeping, but I didn’t know if there was anything significant enough in Deets. Suzanne convinced me there was.

Dyson Lovell We were thinking we had Charles Bronson for Blue Duck, but we didn’t. That was a very difficult part to cast.

Lynn Kressel We really wanted a Native American for Blue Duck, and we visited some reservations, but the actors didn’t surface. I kept getting calls from Frederic Forrest’s agent, who said, “You know, Freddy is half-Native American.” So finally we needed the actor in about a week and made the offer. Sure enough, the agent calls and says, “Well, Freddy thinks the role should go to a Native American actor.” I said, “You kept telling me he was Native American!” Agents are such liars.

Merritt Blake was Frederic Forrest’s agent. Not this one. I do think Forrest had some Native American blood, but he wanted the role to go to a true full-blooded Native American.

With filming set to begin in March, the “mass prep hysteria,” as costume designer Van Ramsey called it, moved to the shooting locations, first in Austin and eventually Del Rio, the crew readying their wares and the actors figuring out their characters and one another.

Tommy Lee Jones As they were putting the score together, I was asked what theme would suit Call musically. I said the “Blue Bells of Scotland,” because in the book he is from Scotland. He’s very stern and probably a Calvinist Presbyterian. They worship a vengeful God and are not afraid to take action on his behalf. Pretty tough hombre.

Robert Duvall About a month before we started, I looked up a classmate, a rancher near Rotan, and he took me to see Sammy Baugh [the NFL great who played quarterback at Texas Christian University in the thirties]. I thought, “Wow.” My dad took me to see him play with the Washington Redskins when I was ten. But he must have been seventy when I met him, and he didn’t even know who I was. We talked for hours about football and his life, and he just seemed to me like an old, tall Texas Ranger. So that’s where I got my gestures and everything, watching Sammy Baugh.

Danny Glover I had to make some assumptions about Deets. I decided he was Black Seminole, that he’d worked for Santa Anna’s government before the Civil War, then came back and scouted for the Rangers. He could be close with Gus and Call because back then, responsibility was given based on your capacity to take on responsibility. They trusted each other.

Bill Wittliff Everybody was showing up for preliminary stuff—to get a horse, make sure they could ride, get their costume and hair—when I get a call. “Bill, you’ve got to come out here.” I said, “What’s the problem?” and they said, “Well, Ricky’s here . . . and you’d just better come.” So I go out there and find Ricky in one of those masks like they wear in Mexico during flu epidemics. I thought, “My God, what have we done?” But that mask flew off his face within ten minutes of being around Tommy Lee and Duvall. Nobody wanted to look bad around those guys.

Bill Sanderson portrayed Lippy Jones. Tommy Lee came to pick me up for rehearsals but wouldn’t come into my hotel. I said, “Why are you lurking outside?” He said, “I don’t lurk. I loom.”

D. B. Sweeney portrayed Dish Boggett. I tried to latch on to Dish’s skill as a horseman and a roper. All his confidence came from being top hand. But I lived in New York, where the only way to practice riding was on horse trots in Central Park. So I showed up in Austin the first day they had horses. Well, Tommy Lee came down too, because he had concerns about a New Yorker playing Dish. He invited me to his ranch in San Saba to help doctor two hundred head of cattle that he had. He put me on this immature polo pony, maybe hoping I would break my neck and be replaced by someone from Texas.

Bill Wittliff Tommy Lee gave D.B. a little cowboy school of his own.

Van Ramsey was the costume designer. Robert Urich [who died in 2002] would not come to fittings. He said, “Design it to fit my stunt double.” He shows up the night before his first scene, and the man has gained forty pounds! The shop was up all night long making new clothes. We split his vest open in the back to get it on him.

D. B. Sweeney That casting of Urich was brilliant. A part of Jake is incomplete. And anybody looking at Urich next to Duvall and Tommy Lee would say, “What’s wrong with this picture?” Bob had that feeling of being incomplete, that he didn’t have the chance to do great roles. That insecurity made his Jake very interesting.

Chris Cooper portrayed July Johnson. I remember spotting Duvall in a hotel lobby surrounded by a crowd of civilians. He was in character, telling this story about getting his horse shot out from under him in a shoot-out with the Indians. It was beautiful.

Cary White We built these faux outhouses around Lonesome Dove, and Duvall would take a crap in them because he was in character.

Barry Tubb portrayed Jasper Fant. Every morning, Duvall showed up at the catering truck and said, “We’re making The Godfather of westerns.”

Robert Duvall I loved saying that because one of the makeup guys was connected with the mob in Brooklyn. He’d always say, “Whaddayamean? No way!”

The shoot began on March 21, and for the next three and a half months the cast and crew worked to pack the long months of McMurtry’s trail drive into six and a half hours of television. Sequences with cattle were among the most difficult, relying as they did on livestock disinclined to direction and a number of actors who’d been cowboys for only a few weeks.

Bill Wittliff People could absolutely have gotten hurt if they didn’t know what they were doing. One time the lead steer swam into the middle of the river and started circling, and the rest of the cows followed and couldn’t get out. I thought, “My God, we’re going to lose the whole herd.” Suddenly everybody became real cowboys. The cast and wranglers jumped on their horses, piled in the water, and turned the herd. We weren’t even filming.

Barry Tubb You learned real quick who could ride, because the first cattle drive sequence was when we had to ride naked. I remember us all sitting around between takes, wearing nothing but our chaps, when Jones walked up. I hadn’t seen that I was sitting in his chair. “Oh, shit, sorry, Mr. Jones.” He said, “Naw, sit back down. There’s no ceremony here,” and went and sat on a log. That was the beginning of him getting his cowboys together.

Tommy Lee Jones The majority of them had no experience moving large numbers of cattle over long distances. I saw them take great pride in getting better at that, like any bunch of green kids starting out on a trail drive. It was kind of cool.

Among the most memorable scenes were the snakes . . .

Bill Wittliff Everybody always wants to know about the snake scene. They say, “How’d you do that?”

Billy Burton was the stunt coordinator. Half the snakes had been brought in from Thailand, nonpoisonous obviously, and half were rubber. We attached a fake one to the kid’s cheek, then did what we call a reverse load in the camera. We filmed the snake being pulled off his face and then played it backwards.

D. B. Sweeney The New Yorker in me kicked in for that scene. I said, “I’ll be fine over here while you shoot that. I don’t need to be in the water for that one.”

. . . and the San Antonio saloon . . .

Simon Wincer I rather like the way Tommy Lee knows what’s coming in the bar and shuffles slightly sideways just before Duvall whacks the guy. This insolent bartender doesn’t appreciate all they did for Texas? It’s a bloody insult.

Cary White We filmed old San Antonio in Brackettville, and Tommy Lee said, “The Germans were a big part of San Antonio. Where are the signs in German?”

Tommy Lee Jones That’s true. I did. And after lunch, there were four German signs hanging from stores like there should’ve been.

. . . and Gus and Lorena by the creek.

Diane Lane portrayed Lorena Wood. At one point Duvall decided that to get the proper reaction he’d flash me for real. That “shriveled my pod” bit? I’m telling you, he loved Gus.

No movie set is free of conflict. The tension on Lonesome Dove came from Forrest and Duvall and their battles with Wincer. Forrest had been an Oscar nominee for 1979’s The Rose and a co-star of Duvall’s in Apocalypse Now. But by the late eighties he was playing a cop in the Gen-X TV series 21 Jump Street. When Forrest and Wincer fought, Wincer won. Duvall, on the other hand, was at the top of the marquee, a four-time Oscar nominee who claimed the Best Actor trophy in 1984 for Tender Mercies. In many ways he owned the production the same way he did the final product.

Van Ramsey Everybody had Charles Bronson in their head, and then Fred Forrest showed up. Fred is the better actor, but it’s hard to replace somebody if you’re a totally different type.

Bill Wittliff He’s a good Blue Duck. And he’s up on the screen, so he’s Blue Duck forever. But his [prosthetic] nose did fall off a couple times.

Van Ramsey At two o’clock in the morning, Fred was getting ready for one of the first times we see Blue Duck. He ran into Tommy Lee in makeup, and Tommy Lee brings up this thing. “Wouldn’t it be interesting,” he said, “if you wore a woman’s dress, like you had just killed a woman and put her dress on?” And they proceed to get a dress off the trailer. I called Bill. “You better get to the set. You will not believe this thing happening here.” So there’s a back-and-forth . . . and anyway, the dress was canned.

Simon Wincer Duvall hated the casting of Frederic Forrest. So Blue Duck’s first scene, when he rides down to the stream where Duvall’s on the rock and Lorena’s hiding in the bushes, Duvall refuses to rehearse with him. It turned out great because it gave the scene a powerful edge. They were feeling each other out, two old archenemies looking at each other for the first time.

Billy Burton My cowboy friends always ask about one scene. There’s that sequence when Duvall’s looking for Lorena and that ragtag band of comancheros shoot at him. He’s sitting on his horse, drinking from a canteen, and the bullet’s supposed to land between the horse’s front feet. So we placed a squib [a small pyrotechnic] right there, rolled the cameras, and when the squib went off, the horse bucked.

Billy Winn was an animal wrangler. Threw his ass off big-time. And damn, they never cut nothing. Duvall held the bridle and jumped back on. Ninety-nine percent of actors would have hollered for the paramedics and a stuntman. But not Duvall. He just mounted up and went on.

Doug Milsome Bob thinks a director is just there to be a traffic cop, to put him in position. He’ll kick against direction if he feels it disparages his concept of what he’s doing.

Barry Tubb Simon asked for a second take once, and Duvall said, “How long have you been in this business?” Simon says, “Seventeen years.” And Duvall says, “I’ve been in it thirty-five f—ing years, Junior!”

Ricky Schroder He called him Junior.

Billy Burton I remember one day he told Simon, “I’ll bite your f—ing nose off!”

Barry Tubb He hates Australians. The director of Tender Mercies, Bruce Beresford, was Australian, and there was a story about Duvall chopping his director’s chair up with an ax.

Robert Duvall That never happened. But Australians do tend to have an attitude. They remind me of Argentines. Talented people, but they’re from so far away, yet they’re going to come show us how to do it?

Chris Cooper It was not the most comfortable situation. In the scene where we save Diane, when Gus kills a few Indians and I don’t get a shot off, his gun wouldn’t fire. Bobby got hot, flung the weapon, and missed my head by about a foot and a half.

Diane Lane He threw that pistol from up on a hill, and it landed not far from me down in the camp. That thing must have weighed fifteen pounds.

Danny Glover Some actors need tension to feed off of. But I did hear some language that I never heard an actor throw at a director before.

Simon Wincer It’s no secret that Bobby and I had our moments. But I don’t care. What we ended up with is fantastic.

Bill Wittliff When we shot close-ups, I’d literally lean in, just short of touching the camera, to watch Duvall. And I’d come away saying, “Yeah, Gus, that was wonderful.” Then the next morning I’d watch the dailies, and there would be stuff you cannot see with the naked eye. Like when Jake’s hung. Go back and look at that. When Jake spurs his horse, Duvall does this little flinch, this little blink, and it is so real. It’s just [snaps his fingers] that fast.

Robert Duvall When we hung Jake Spoon, Simon says, “Do you want one more take?” And I am glad he said that because something happened to me, this strange, split-second, emotional reaction. There was no logic to that flinch. It just happened.

But then, when I saw the first cut—and thank God I saw it first—they’d cut that out. I could only think they were trying to get back at me. Well, I called Dyson. He was an ally.

Dyson Lovell I fixed it immediately.

By the time the big cattle sequences were wrapped, in late May, the cast had had their fill of trail driving and, in some instances, one another. The production moved to more civilized Santa Fe, where Anjelica Huston joined on. She was Hollywood royalty, the daughter of John Huston and an Oscar winner for 1985’s Prizzi’s Honor. Eventually, the mood on the set relaxed. The small tango parties Duvall hosted in Del Rio grew into lavish soirees. Problems that arose were more manageable.

Anjelica Huston portrayed Clara Allen. I’d been in England making The Witches before coming to Lonesome Dove. The first day there, my wardrobe comes to my trailer, and I thought, “Oh, my God. I’ve made a terrible mistake.” Van and I had chosen Victorian petticoats and sunbonnets for Clara, the wardrobe of a perfect lady of the house. I ran to the costume trailer. “Van! I have to rough this woman up.” He let me in the guys’ costume trailer, and I came out with filthy boots and sweat-stained shirts.

Barry Corbin I’d filmed some scenes when the cast first got to Austin, and everybody was as happy as could be. Then I left for three months and hooked back up in Santa Fe. Everybody was surly. I asked Tim Scott about it [Scott was the career western character actor who portrayed Pea Eye Parker. He died from lung cancer, in 1995]. He said, “It was the cattle drive. You didn’t have to do the cattle drive. You’d be mad too.”

Bill Sanderson Tim was a sweet man. Real knowledgeable about horses. And very careful. When we had to push that wagon up out of the mud and I fall down and get that mouthful of manure, Tim was the one who made sure the wagon didn’t roll back on me.

Bill Wittliff Tim didn’t want Pea Eye to be a “yuk-yuk” buffoon. Like when he and Gus are in the cave holding off the Indians. All of a sudden Duvall yells in Comanche, “Awk! Awk! Awk!” and Tim jumps. And later Duvall tells him to head south, and Tim says, “South?” Duvall responds, “That way yonder. If you run into a polar bear, you went the wrong way.” That’s all funny. But you never lose the scary aspects of their predicament. In almost every one of Pea’s scenes, there’s a point where it could have fallen off the bridge. But Tim gave Pea such dignity.

Throughout the story, the layabout Gus does undertake one great, overriding mission: to make Call feel. It’s the heart of their friendship as well as the narrative. When Gus realizes he’s dying, he senses one last opportunity, and in Wittliff’s script, the scene played out over seven pages. The network felt it could be told in half that, but Wittliff, who knew he could put his faith in the chemistry between Duvall and Jones, refused to budge. (The scene does contain one moment that should have been reexamined: In the novel Gus loses his left leg; in the miniseries it’s his right.)

Barry Tubb Jones and Duvall both received tapes of the dailies, and if you’d go to Duvall’s house, he wouldn’t be watching his own stuff. He’d be watching Jones, saying, “Watch this son of a bitch . . . right here!” And you’d go to Jones’s house, and he’d be watching Duvall. It was like an actor’s duel. They were raising the bar on each other.

Dyson Lovell Gus’s death scene wasn’t even rehearsed. Bobby and Tommy Lee knew what it would be. The banter between them was wonderful. One man is dying and the other one knows it.

Simon Wincer Call says, “You want me to haul you back to Texas?” You can hear it in his voice: He doesn’t get it, but he does it.

Dyson Lovell The network was concerned that once Gus died the audience wouldn’t be sufficiently interested in Call to watch him hauling the body to Texas. They needn’t have worried.

Chris Cooper When Call leaves Clara’s horse ranch with Gus, Duvall brought music to play before the scenes to get Anjelica and Diane in the emotional state necessary for their goodbyes.

Anjelica Huston Bobby knew that I had grown up in Galway and that the song “Galway Bay” stirs me. In the scene where he leaves Clara forever, he played it on his tape recorder as he rode away, and the tears flowed freely.

Diane Lane Bobby found some sheet music from that time, a song called “Lorena,” and recorded somebody playing it on an old piano. At the moment I find out that Gus is dead, Bobby played that music and stood just outside the action.

Simon Wincer The final scene. We had a kid playing the reporter who’d never been on-screen before, and I could see the sun going really fast. So as we were rolling, I said, “When I say, ‘Cut!’ I don’t want anyone to talk. I’ll give instructions for the B camera to run to the other side of the bridge for a wide shot of Call walking off.” So we do the first shot, the close-ups. The reporter says, “They say you’re a man of vision,” and Tommy Lee picks his moment. “Yeah, hell of a vision.” You can see the tears in his eyes. I say, “Cut!” the cameras move, and bang! We get him crossing the bridge literally as the light went out.

Tommy Lee came to me afterwards and said, “When you can feel the whole team sweating to get one shot perfect, it’s like playing sports with someone better than yourself. Everybody rises to the occasion. That was absolute magic.”

The initial reviews of Lonesome Dove were somewhat mixed. Newsweek said it “proves what television can achieve when it forgets it’s only television,” and Time claimed it offered “the most vividly rendered old West in TV history.” The New York Times, on the other hand, called Newt a cliché, Deets a caricature, and July and Lorena ciphers. No matter. When it aired over four nights, beginning Sunday, February 5, 1989, it trounced its competition each night and was the best-rated miniseries in five years.

That fall it was nominated for eighteen Emmys but, in a major surprise, won only a single high-profile award, for best director. The six actors nominated, including Duvall and Jones, were shut out. And the Emmy for best miniseries went to War and Remembrance, a $100 million debacle that tanked in the ratings. But that sting faded quickly. War and Remembrance became the answer to a trivia question, and Lonesome Dove became a cultural touchstone.

Bill Wittliff That first night, Sunday, a big cold front dropped out of Canada and settled over the United States. So people were home. They started watching. And they called their friends and said, “You’ve got to tune in to CBS.” A week after it aired, guys were wearing buttons that read “How about a poke?”

D. B. Sweeney I couldn’t buy a beer in Texas for the next ten years. I would take my wallet out in a bar in Austin, and the bartender would say, “That guy down there says Dish Boggett drinks free.”

Stephen Harrigan My claim to fame is, I was an extra in the movie. People hear that and are amazed. It’s like being a munchkin in The Wizard of Oz.

Doug Milsome I now live in the deepest, most rural part of England, and the farmers here all borrow it. I can’t lend it out enough. They’re hooked.

D. B. Sweeney I visited the troops in Iraq and Afghanistan and met these two fighter pilots. One of them said, “We were on our first combat mission into Afghanistan, and my buddy comes over the radio and says, ‘I guess this is where we find out if we was meant to be cowboys.’” They couldn’t have been five years old when Lonesome Dove aired.

Robert Duvall I was fortunate enough to be in the biggest thing in American cinema history and American television history, The Godfather, parts one and two, and Lonesome Dove. Now, The Godfather was better directed, but the novel was only okay; the movies went beyond it. For Lonesome Dove, we had to do everything we could to come up to the level of the novel. Whether we really did, I don’t know.

Bill Wittliff I have a view about great art, whether it’s stories, poetry, music, whatever. None of it tells you anything new; it merely reminds you of something you already know but forgot you knew. And that’s what Larry did. You start reading Lonesome Dove, and you feel you already know these people. That’s its great magic.

Larry McMurtry We still don’t know that it is a classic. It hasn’t been long enough to make that assessment. I’ve said myself several times that it is the Gone With the Wind of the West. That means making a judgment about both books. Gone With the Wind is not a despicable book. It is also not a great book. And that is what I feel about Lonesome Dove.