The holy warriors of the anti-doping crusade have achieved the near-impossible: They have made me feel sorry for Roger Clemens. When George Mitchell’s report on the use of performance-enhancing drugs in baseball, requested by commissioner Bud Selig, made Clemens its poster boy, the reputation of one of the best pitchers the game has witnessed was instantly destroyed. The allegations were based almost entirely on the testimony of Clemens’s former personal trainer, Brian McNamee, who was threatened with prosecution if he lied to Mitchell’s investigators. That’s what the crusaders were waiting for, a big name, someone less odious than, say, Barry Bonds. We may learn the truth from the upcoming FBI investigation into whether Clemens committed perjury, or the conflict between Clemens and his accusers may remain unresolved, but either way, the damage is done. “Mitchell has thrown a skunk in the jury box,” Rusty Hardin, Clemens’s Houston-based attorney, told me. “Whatever happens now, we’ll never be able to remove the smell.”

A shadow of suspicion has trailed Clemens since October 2006, when the Los Angeles Times reported that an affidavit for a search warrant, sworn to by a federal investigator, fingered McNamee, Clemens, and several other players in a performance-enhancer drug case. Clemens steadfastly denied using performance enhancers (and, indeed, fourteen months later, the Times ran a correction saying that he had not been named in the affidavit after all). He repeated those denials after the Mitchell report appeared in December, first in an interview with Mike Wallace on 60 Minutes, in which he admitted to taking injections of vitamin B12 and the painkiller lidocaine but angrily rejected McNamee’s contentions that he’d received steroids and human growth hormone (HGH), then in a press conference so packed with self-righteous indignation that he stormed off the stage when the questions got too sticky.

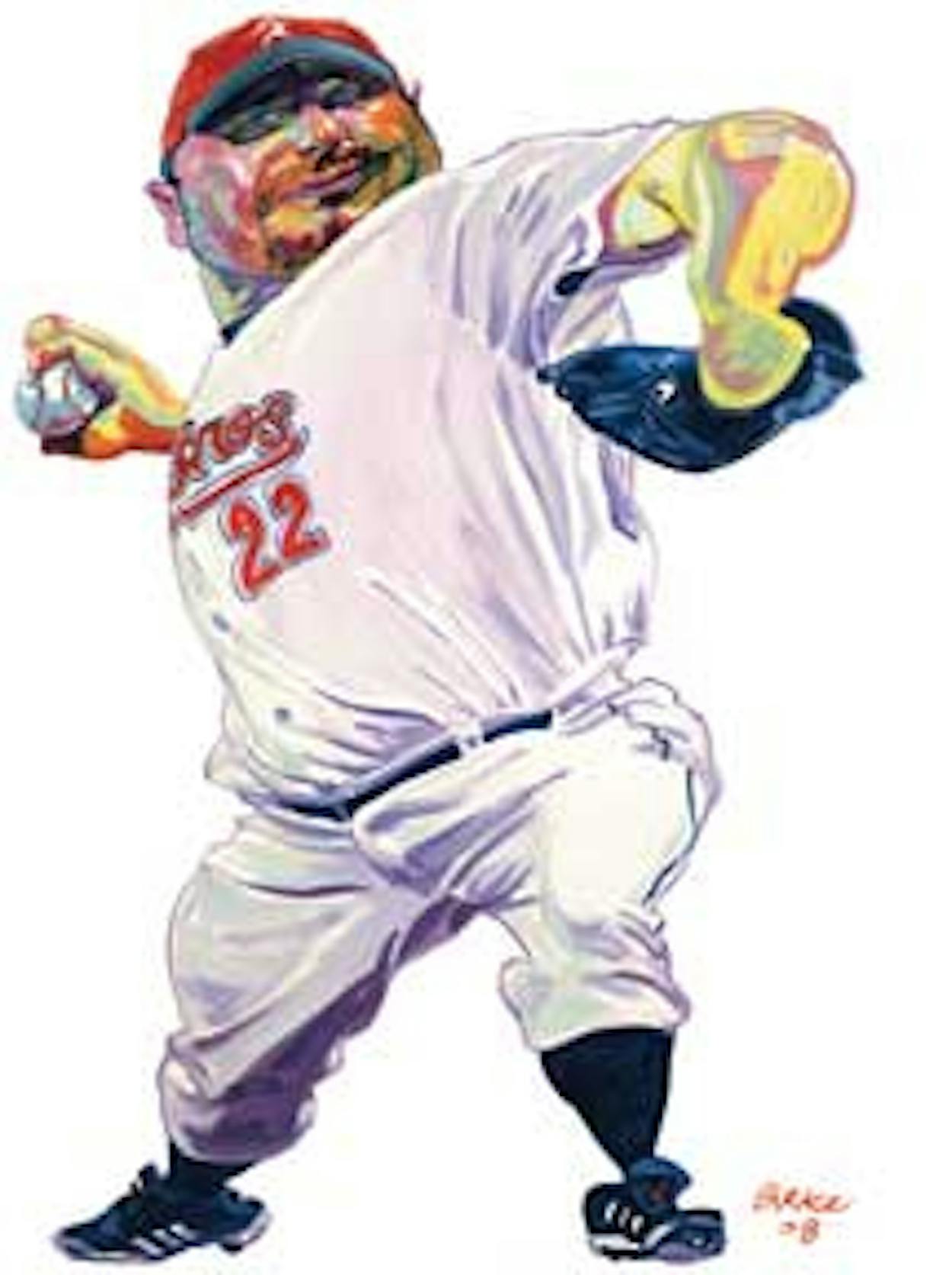

To rebut allegations that Clemens’s career rebounded about the time he supposedly first started using performance enhancers, his agent, Randy Hendricks, released an 18,000-word report, complete with statistics, maintaining that his remarkable longevity (Clemens is 45) was due to his ability to adjust his pitching style. To compensate for a decrease in the velocity of his fastball, which had been his trademark since he broke in with the Boston Red Sox, in 1983, Clemens, the report said, utilized a split-finger fastball. Indeed, he won the fourth of his seven Cy Young awards in 1997, at age 35, a year after the Red Sox decided he was washed-up and a year before McNamee claims that Clemens started using steroids.

On February 13, Clemens went to Capitol Hill to repeat his denials, this time under oath. The House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform had all but commanded his appearance, because he had dared to challenge the Mitchell report. “How did we reach the stage where a guy is criticized for publicly denying guilt?” Hardin asks. Clemens hasn’t been charged with a crime, but the court of public opinion has already rendered its guilty verdict.

It’s almost as though the holy warriors were waiting for a star of Clemens’s magnitude to make it official that performance enhancers are our newest national hysteria, nudging aside old standbys like bird flu, sharks, and red hordes. This has gone beyond silly. Who among us hasn’t used performance enhancers, preferably with ice and an olive? Steroids, synthetic substances similar to testosterone, can be as benign as those that are commonly prescribed for allergies and as harmful as those that have sent many retired athletes into physical decline; as with any medication, the effect depends on the dose and frequency of use. Anabolic steroids, the type that bulk up muscles, are used to treat certain kinds of anemia and offset the loss of testosterone caused by aging. I’ve taken them and regularly use a steroid nasal spray. My dog Allie takes steroid shots for her hot spots. Another type of steroid, called a corticosteroid, is used to reduce swelling. The real question ought to focus on intent: If an athlete uses steroids to change his body, as Barry Bonds apparently did, the public has every reason to be outraged. If an athlete uses them to combat aging, so what?

All steroids enhance performance and, if misused, can cause trouble. There have been a few cases where the premature death of an athlete was possibly the result of steroid use, most notably those involving Lyle Alzado, a defensive end for the Denver Broncos, who believed that steroids were the cause of his fatal brain lymphoma, and Houston Astros and San Diego Padres slugger Ken Caminiti, a user of cocaine and steroids who died of a heart attack at 41.

For the most part, however, the only thing certifiably bad about steroids is that they may improve athletic performance. Somehow we’ve decided that the only hardworking professionals who shouldn’t be permitted to enhance their performances are athletes. Amphetamines were staples in professional training rooms in the sixties and seventies—Jim Bouton’s book Ball Four, published in 1970, is full of talk about popping “greenies”—and are still widely used. “Amphetamines are the real performance-enhancing drugs that people should always have been worried about,” Allan Lans, the New York Mets’ team psychiatrist from 1987 to 2003, told the New York Times recently. The mind-set of the elite athlete is, do anything it takes to get an advantage. Athletes training for the Beijing Olympics have asked the physiologist for the U.S. Olympic Committee if they should acclimate themselves to the city’s dreadful pollution by running behind buses and breathing the exhaust. In his 60 Minutes interview Clemens cheerfully admitted that until the painkiller Vioxx was taken off the market, he gobbled it “like it was Skittles.”

Clemens is one of the game’s more unlovable athletes, which may explain why nobody will give him the benefit of the doubt. He’s not as reviled as Bonds, though the differences are more a matter of style than substance. Whereas Bonds is arrogant, sullen, and menacingly taciturn, a volcano of resentment waiting to erupt, Clemens is profane, inarticulate, and in-your-face aggressive. He once threatened bodily harm to a writer who accused him of being a “head case.” His reputation helps reinforce the circumstantial evidence against him.

All pitchers try to intimidate hitters, but Clemens seems to delight in the act, as demonstrated by two infamous incidents involving All-Star catcher Mike Piazza, then with the Mets. In an interleague game between the Yankees and the Mets in 2000, Clemens beaned Piazza with a fastball, resulting in a concussion that threatened Piazza’s career. In the World Series that same year, Clemens picked up the head of Piazza’s broken bat and threw it at him as he raced toward first. McNamee told investigators he had injected Clemens with testosterone four to six times in 2000. Was it ’roid rage that made him go after Piazza? Or just competitive zeal?

Clemens refused to talk to the Mitchell team. Now nobody can shut him up. He didn’t help himself with his evasive, self-serving, and sometimes childish remarks on 60 Minutes. If he really had used steroids, he smirked to Mike Wallace, why wasn’t there a third ear coming out of his forehead? He was an even less sympathetic figure after his press conference, in Houston, so defiantly defensive that at one point Hardin passed him a note that said, “Lighten up.” The highlight of the press conference was a seventeen-minute audiotape that Clemens had secretly recorded of a conversation with McNamee, who desperately wanted his old friend to understand that the feds had him by the balls and he had no choice except to talk. The tape ultimately answered no questions but did pose one: Who was the real lowlife in this relationship? Clemens shrugged off suggestions that his legacy was in jeopardy, saying he didn’t “give a rat’s ass” about the Hall of Fame.

Although baseball had banned steroids in 1991, they were nevertheless deeply embedded in the game’s culture by 1998, the year that McNamee told Mitchell that drugs had become part of Clemens’s rigid training routine, which awestruck teammates called “Navy SEAL workouts.” McNamee had just landed a job as a strength coach with the Toronto Blue Jays, for whom the 36-year-old Clemens had won a Cy Young Award the previous season after spending thirteen years with the Red Sox. It’s not clear when McNamee claims to have started giving Clemens injections, but after a mediocre start, Clemens was almost unhittable from June through September, posting a 15-0 record and a 2.29 ERA.

Baseball wouldn’t start testing players for steroids until 2003, so there are no drug tests that could implicate Clemens and impeach his testimony. However, there may be other physical evidence that could expose Clemens to criminal charges of perjury. McNamee has turned over to federal investigators bloody gauze pads and syringes that he says he used to inject the baseball star in 2000 and 2001. The pads may contain Clemens’s DNA, though surely it is contaminated after all this time. And there could be another uncorroborated piece of evidence. McNamee now claims that he gave injections to Clemens in 1998 that caused an abscess on Clemens’s buttocks, not an uncommon side effect for anabolic steroid users. It is not clear from medical records if Clemens’ sore butt was caused by an abscess or something as simple as a bruise, but the trainer, the general manager, and the team doctor for the Blue Jays at the time have all told the New York Times they don’t recall an abscess. Credibility, it would appear, is not one of McNamee’s strong suits. According to a report released by the police in St. Petersburg, Florida, where the Yankees stayed while playing the Tampa Bay Devil Rays, McNamee lied several times during a 2001 investigation into a possible rape reported at the team’s hotel. The victim was given a near-fatal dose of GHB, a drug taken by bodybuilders and sometimes used to facilitate date rape. Charges were never filed.

Clemens seemed nervous at the congressional hearing, licking his lips, wrinkling his brow, insisting that if he was guilty of anything, it was being too nice to people. The most damaging testimony came not from McNamee but from Clemens’s friend and former teammate Andy Pettitte, who had already taken Clemens by surprise by admitting that he’d gotten injections from McNamee; another former teammate, Chuck Knoblauch, admitted the same thing. Of the three players McNamee had fingered, two had confessed. But Pettitte may have done his friend lasting damage when he told the committee that in 1999 or 2000 Clemens confided that he had taken HGH. At first Clemens denied such a conversation had taken place. Later, he claimed that Pettitte had “misremembered” a conversation in which Clemens told him that his wife, Debbie, had taken an HGH injection from McNamee. But the denial did not fit the timeline: Debbie got her injection four years after that misremembered conversation. Clemens’s testimony was full of inconsistencies, apparent lies, and one enormous unanswered question: Why would McNamee tell the truth about injecting Pettitte and Knoblauch but lie about Clemens?

Its rush to judgment aside, the Mitchell report may have performed a public service by shooting holes in some of baseball’s more suspect myths. Start with the illusion that drugs are destroying the integrity of the game. Integrity? Oh, you mean like the monopoly that Congress gives owners, granting them an exemption from antitrust laws and allowing them to thumb their noses at the public while juiced-up stars such as Mark McGwire and Bonds smash the game’s most cherished home run records? You might say the real victims of steroids are Hank Aaron and Babe Ruth. Meanwhile, owners bulk up on steroids without having to actually take the nasty things. Baseball revenues soared as home run records fell, jumping from $2.9 billion in 1998 to just over $6 billion last year.

Then there is the myth that steroids are turning players into freaks. Players have always been freaks. That’s what makes them so different from the rest of us. No normal person can throw a baseball 98 miles an hour. Normal people can’t run a slant-in and catch a football with a 250-pound linebacker waiting to cream them. Baseball is no more egregious than professional football, but cheaters are easier to identify because baseball is a game intoxicated with statistics, such as Clemens’s 354 career wins or Bonds’s 762 career home runs.

It is time to admit that not all steroids are dangerous and that every individual and every situation cannot be addressed with the same set of rigid rules. Instead of banning steroids, we should control them. Cool the hysteria; educate without scaring. Understand the problem. “There is a tipping point in a player’s career where he goes from chasing the dream to running from a nightmare,” former big-league outfielder Doug Glanville wrote recently in an essay published in the New York Times’ op-ed page. “At that point, ambition is replaced with anxiety, passion is replaced with survival.” If an athlete like Clemens needs medication to overcome the aches and pains of aging and the fear of failure—if he needs a little help to keep on keeping on—whose business is it, anyway?

Granted, the use of performance enhancers sends a bad message to young people, but so do a lot of other things, like drinking and smoking. Hasn’t our collective experience taught us that prohibition doesn’t work and that we can’t totally kid-proof society? A larger problem with liberalizing the use of steroids is that players who want to compete might be forced to use them against their wishes. That happens, beyond a doubt. We need to make a distinction, as previous generations did, between amateurs and professionals. Sports on an elite level is an inherently unhealthy pursuit; professionals define themselves by what they are willing to do to succeed. Washington Post sports columnist Sally Jenkins has written that “world-class athletes are in the business of torturing their bodies unnaturally,” of changing the body’s chemistry and pushing it to unnatural extremes. It’s the price they have agreed to pay.

So let’s give poor Roger Clemens a break. He’s not a drug addict or even a serious abuser. In the four-year span that McNamee claims to have juiced Clemens, he took a total of maybe sixteen injections—hardly enough to account for a career of greatness or do any harm to the game. Now he faces a perjury investigation that comes down to his word against his accusers’. It seems as if Roger Clemens is being prosecuted not just because he may have used steroids but because he acted like a jerk.