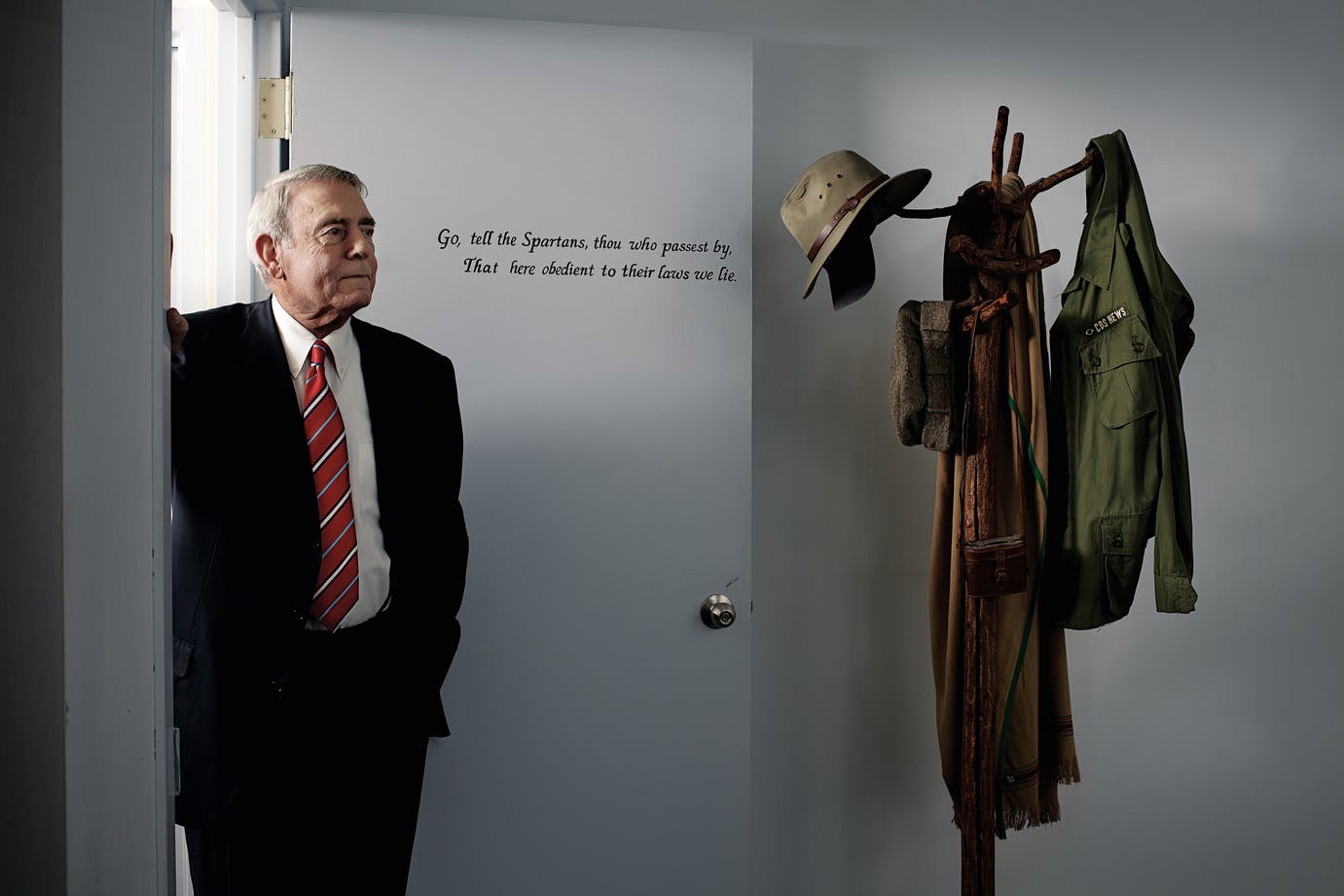

Here it is, on a coat hook in midtown Manhattan: the Army-issue green shirt, with “CBS NEWS” written in white letters on the ID tag, that Dan Rather wore in 1966 while hunkered down in rice paddies along the Cambodian border. It would be one of the legendary network anchor’s most famous assignments: dispatching dramatic reports on the Vietnam conflict for millions of Americans sitting down to the evening news. In 16mm films you can see him, young and square-jawed, hair thick and black, barking into a microphone and recoiling from machine guns that rat-a-tat-tat behind him.

“It’s a little tighter than it used to be,” says Rather, considering the shirt now.

He’s sitting under a still-life painting of a fishing rod and tackle in his modest, somewhat shabby little office on Forty-second Street, a place hidden at the far end of a long hallway where you’d least expect to find the former anchor. His lower lip bulges, as if swollen from a punch to the mouth, with a pinch of tobacco, a vestigial habit from his teenage years working on Texas oil rigs. Craggy, gray-haired, and in need of hearing aids, Rather is still animated by his glory days, the details of which have long since solidified into a personal mythology. It’s the epic story of the hustling correspondent from Wharton who reported the death of President John F. Kennedy as a young CBS correspondent, who brought Vietnam into American living rooms, who stood toe-to-toe with Richard Nixon during Watergate, and who nudged aside Walter Cronkite to become one of the most trusted and iconic voices of his day.

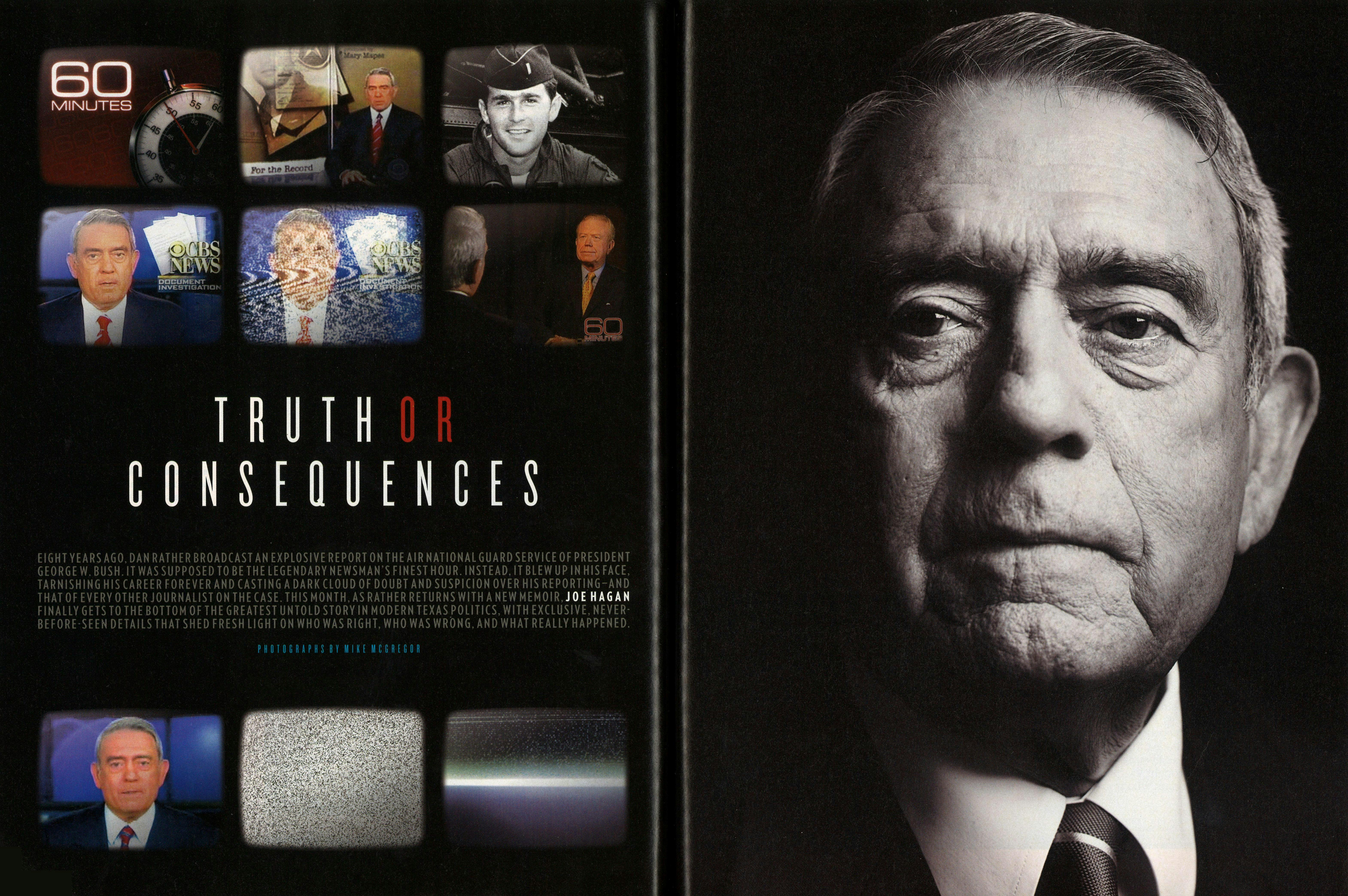

By all rights, Rather, who turns 81 this year, should be enjoying a few victory laps at the close of a remarkable career. And he would be, except for one report that he will never forget, because no one will ever let him: the botched 60 Minutes segment in 2004 on George W. Bush’s Texas Air National Guard service. The report, which lasted fifteen minutes, forever damaged Rather’s reputation and ended his network TV career after forty years. Its claims were potentially explosive—that Bush had received preferential treatment to enter the National Guard in 1968 in order to avoid the Vietnam draft and that he had then shirked his duty without repercussion. As evidence, Rather produced six documents that described the alleged political pressure Bush’s commanding officer was under to “sugarcoat” possibly embarrassing moments in Bush’s record, specifically his failure to show up for a flight physical and his loss of flight status. In a presidential campaign that had become a referendum on who had the credibility to take control of the quagmire in Iraq, Rather’s report could have seriously damaged Bush’s reelection effort. But he went at the king—and he missed.

Almost as soon as the broadcast aired, a swarm of right-wing blogs assailed Rather’s documents, claiming their typeface and spacing was inconsistent with any known typewriter of the early seventies. Within days CBS was reeling as Bush allies accused Rather and his longtime producer, Mary Mapes, of using forgeries to tip a presidential election in favor of the Democrats. Twelve days after the story aired, CBS backed down, forced Rather to apologize, and established a special panel to investigate what went wrong. Forty-three days later, Bush was reelected, beating Senator John Kerry by a two-point margin in the pivotal swing state of Ohio. By the time Mapes and three other producers were ousted by CBS, the Bush National Guard story was dead and buried, with Rather’s reputation as the tombstone.

Eight years later, Bush is back in Texas, keeping a low profile and building his presidential library. Rather is still a newsman, hosting a program called Dan Rather Reports on HDNet, a niche cable and satellite channel. But he is also a man who cannot stop reliving his worst moment. This month he will publish Rather Outspoken: My Life in News, his fourth memoir but the first since his downfall. Not surprisingly, he uses the book to defend the details of his report, sharpening his ax for Bush, as well as former colleagues at CBS and its parent company at the time, Viacom, whom Rather believes caved under political pressure from the Bush White House.

“The story we reported has never been denied by George W. Bush, by anyone in his close circles, including his family,” says Rather. “They have never denied the bulwark of the story, the spine of the story, the thrust of the story.” (In fact, Bush officials have indeed denied it, repeatedly. In a conversation I had with former White House director of communications Dan Bartlett in 2007, he told me, “We believe the story is inaccurate, both the general thrust of it and the questionable sources they used.”)

Rather tried making his case in a 2007 lawsuit against his former bosses, but it was thrown out of court two years later. Nonetheless, he remains convinced that he did nothing wrong. “I believed at the time that the documents were genuine,” Rather says, “and I’ve never ceased believing that they are genuine.”

This is nearly impossible to know. The documents were Xerox copies, which in forensics is a dead end—nothing can be proved, or disproved, without an original. Since the report, Rather has hired lawyers and private investigators to get to the bottom of the mystery, to no avail. Strangely, he has made only one attempt to contact the man who initially gave the documents to CBS, the former Guardsman and West Texas rancher Bill Burkett, who, after initially lying about where he got them, told a dubious tale of receiving them from shadowy characters at a cattle show in Houston—and then went stone silent. Burkett refused to talk to Rather.

But the CBS documents that seem destined to haunt Rather are, and have always been, a red herring. The real story, assembled here for the first time in a single narrative, featuring new witnesses and never-reported details, is far more complex than what Rather and Mapes rushed onto the air in 2004. At the time, so much rancorous political gamesmanship surrounded Bush’s military history that it was impossible to report clearly (and Rather’s flawed report effectively ended further investigations). But with Bush out of office, this is no longer a problem. I’ve been reporting this story since it first broke, and today there is more cooperation and willingness to speak on the record than ever before. The picture that emerges is remarkable. Beyond the haze of elaborately revised fictions from both the political left and the political right is a bizarre account that has remained, until now, the great untold story of modern Texas politics. For 36 years, it made its way through the swamps of state government as it led up to the collision between two powerful Texans on the national stage.

And by the time it was over, no one—not Dan Rather, not George W. Bush—would be left unbloodied.

THE BEGINNING

It was the 1988 presidential campaign of Bush’s father that first raised the issue of a privileged son from Texas getting special access to the National Guard—only the privileged son wasn’t a Bush. Michael Dukakis, the elder Bush’s opponent, had recently chosen Senator Lloyd Bentsen, of Houston, as his running mate. One Sunday morning in August of that year, George H. W. Bush’s campaign co-chairman, New Hampshire governor John Sununu, went on TV to attack Bentsen for allegedly helping his son, Lloyd Bentsen III, enter the Texas Air National Guard in 1968. “Someone called Senator Bentsen to point out to him that this special slot, which was rare, came open,” said Sununu, and Bentsen “ran to get his son to fill that.”

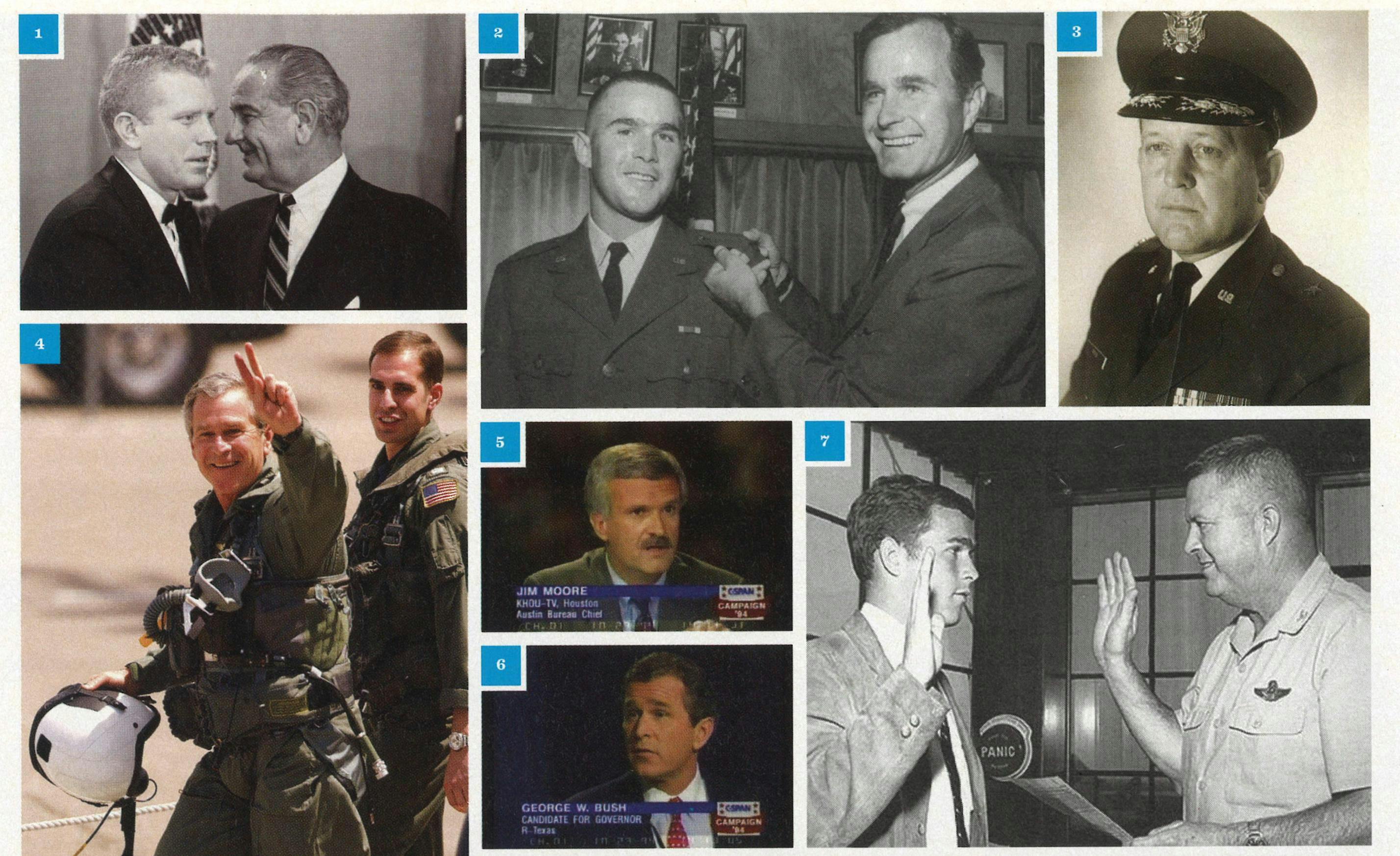

This was the first presidential election in which candidates’ Vietnam-era decisions were resonating among the electorate. The question of who did what in the sixties, when an unpopular war divided the nation, had become a litmus test. (Incidentally, this was also the year that Dan Rather established himself as a Bush family enemy by needling then–vice president Bush with questions about his role in the Iran-Contra affair in an infamous live interview on CBS.) With Democrats attacking the elder Bush’s own running mate, Dan Quayle, for joining the Indiana National Guard during Vietnam, Sununu’s claim was a natural counteroffensive. But it boomeranged. It turned out that George W. Bush, at the time a senior staff member in his father’s campaign, had served in the same Houston unit as Lloyd Bentsen III and was recruited the same year by the same man, Colonel Walter “Buck” Staudt. That unit, the 147th Fighter Interceptor Group, tasked with defending the Gulf Coast, was well-known as a “champagne unit” because it housed not only Bentsen and Bush but a number of other sons of the Texas elite, such as John Connally III, son of the former Texas governor and Nixon treasury secretary; Al Hill, the grandson of oil tycoon H. L. Hunt; and several members of the Dallas Cowboys.

Sununu’s attacks died after Bentsen and Staudt denied the allegations, but the issue had been introduced, and the timing and circumstances of Bush’s entry into the Guard were enough to raise eyebrows. In February 1968, three months before Bush graduated from Yale, the Tet offensive left more than five hundred U.S. soldiers dead in a single week. That same month, Walter Cronkite famously declared the Vietnam War “mired in stalemate” just as President Lyndon Johnson canceled draft deferments for most graduate students. Days before he would become subject to the draft, Bush, whose father was then a U.S. congressman from Houston, won a coveted slot as a pilot in the 147th.

Bush maintains he simply interviewed with Staudt and was accepted on the spot. That may be true, but it would be hard to argue that there weren’t more-qualified candidates: Bush received the lowest acceptable score on his pilot aptitude test.

In 1988 Staudt, by most accounts a bullying, cigar-chomping autocrat, told reporters that there had been no “hanky-panky” involved in getting Bush and Bentsen into the Guard, and he repeated that defense in 2000. But suspicion was not unwarranted. There was a long list of men trying to get into the Texas National Guard. And several months after Bush entered, Staudt paid a visit to Washington, D.C., and lobbied the elder Bush for funding for Ellington Air Force Base, in Houston, making sure to update him on how well his son was doing.

Control over entry into the National Guard was a hotly fought-over lever of power in Texas. Staudt had considerable influence in Houston, but in a state still dominated by Democrats, the ultimate gatekeeper was his commanding officer and internal rival, Brigadier General James Rose. A Democrat, Rose was a handsome and sophisticated political operator who’d managed to become head of the Texas Air National Guard despite never having been a pilot. Rose had a close political bond with the man who would sit at the center of the Guard story: Ben Barnes, then the Speaker of the Texas House of Representatives.

A fair-haired wunderkind who’d been elected a state representative while still in college, Barnes was widely considered a potential future governor and perhaps even a presidential contender. He was a protégé of President Johnson’s and counted him as a close friend. And he had learned from his mentor the art of collecting political chits as a way of life. Barnes has said he regularly fielded requests for entry into the National Guard, and after assessing the trade-in value of the favor, he would pass them on to Rose to sign off on.

Barnes knew how to work the press too: he was a regular source for the man who was then the CBS White House correspondent, Dan Rather.

Barnes would travel a rocky road after the Johnson era. He was elected lieutenant governor in 1968, but several years later, the Sharpstown stock-fraud scandal erupted, taking down much of the state’s Democratic power structure. Though Barnes was never charged, the scandal effectively ended his political career (and that of Governor Preston Smith and House Speaker Gus Mutscher). Out of office, he evolved into the kind of omnipresent backroom figure everyone either loves or hates, a charming and cunning wheeler-dealer with a huge grin, a firm handshake, and a finger in every pot. “Ugly as a cedar post,” says Houston lawyer Dick DeGuerin, “but he shakes your hand and you know your hand’s been shook.”

It was on Rather’s infamous 60 Minutes segment, in 2004, that Barnes first publicly recounted how he had called General Rose on behalf of George W. Bush in the spring of 1968. Barnes claimed he had received a call from Sid Adger, an oilman in Houston who was a close friend of the elder Bush’s. As it happened, both of Adger’s sons were also in the Air National Guard in Houston, under Staudt’s command. Barnes told me that in the late seventies, while he and Adger served on the board of Texas International Airlines, Adger personally thanked him for helping Bush. “We both knew I had done him that favor,” he said.

Barnes’s story has never been corroborated because both Rose and Adger were dead by the time he first told it publicly. The elder Bush has said he doesn’t recall asking Adger for help, and the younger Bush has denied knowledge of it. But during the 1988 campaign, Rose and his son Mark happened to be watching television together when a report came on about the Bush-Quayle campaign’s attacks on Bentsen. According to Mark Rose, who has never spoken about it on the record before now, his father admitted to him that he’d helped both Bush and Bentsen into the Guard.

“My dad looked at me and said, ‘I signed off on Bentsen’s son going into the Guard, and I signed off on Bush’s son going into the Guard,” said Rose, a former Austin city councilman who is now an energy executive living in Bastrop.

He added, “[George W. Bush] can’t say, ‘I didn’t have any help.’ Staudt didn’t work that way. My dad didn’t work that way.”

Bush’s onetime expert and advocate on his National Guard service, a former personnel officer named Albert Lloyd, agreed with Rose. In an interview conducted shortly before his death, in March, he said that General Rose, who was Lloyd’s direct boss in the sixties, had to have been aware of whose son he was admitting to the Guard—and that Ben Barnes was the likely broker.

GOVERNOR BUSH

None of this, however, was being reported in 1988, and after the elder Bush won the White House, the story died down. No one thought much about George W. Bush’s military records until he decided to run for governor in 1994 against the incumbent, Democrat Ann Richards. The first mention came from a TV reporter for Houston station KHOU named Jim Moore. During a debate in October, Moore asked Bush whether he’d received preferential treatment to get into the National Guard in 1968. Bush replied that most Guard assignments were for only six months and nobody else wanted to spend the extra time it took to train on a jet fighter. “My father, just like my commanding officer said, had nothing to do with getting me in that unit,” he said.

Governor Richards knew there was more to it than that. She had privately asked Barnes about the rumor that he had helped Bush get into the Guard, and Barnes told her that he had. Robert Spellings, who was Barnes’s chief of staff in the late sixties (his future wife, Margaret Spellings, would later become Bush’s Secretary of Education), also told Richards he recalled getting Bush in. But Spellings didn’t remember exactly how it was done and advised Barnes against going public, because Barnes had no real evidence. Richards, who had opposed the Vietnam War, didn’t push it.

But after Bush won the election, Barnes’s story spiked in political value. What was to unfold in Texas over the next five years was a political power struggle, at the center of which was Barnes and his claim about Bush’s military history. It began, of all places, at the Texas Lottery Commission.

Barnes was the chief lobbyist for the corporation under contract to operate the lottery in Texas, a multinational gaming services and technology company called GTECH. He and a partner had cut a sweetheart deal in 1992, when the state launched the lottery, to collect 4 percent of GTECH’s Texas revenue in exchange for maintaining the massive state contract, which was worth about $150 million annually. The deal made him enormously influential as a fundraiser for Democrats. In the mid-nineties, he bought a house on Nantucket and befriended the Kennedy family and John Kerry. To maintain his power and influence, Barnes just needed to protect the GTECH contract.

But when Bush took office, Barnes became a target. Bush’s political architect, Karl Rove, and his chief of staff, Joe Allbaugh, took a keen interest in the lottery’s machinations, requesting that minutes from lottery meetings and weekly reports be sent to them regularly. “The Bushes were paranoid about the lottery,” says George Kuempel, who covered the agency for the Dallas Morning News. “Rove wanted to f— Barnes.”

Bush appointed his own lawyer, Harriet Miers, as chair of the Texas Lottery Commission. As soon as she arrived, Miers began studying the possibility of opening the GTECH contract to new bidders. Suddenly, Barnes needed all the leverage he could get, and one thing he had was the story about how Bush got into the Guard.

About two years after Bush took power in Austin, the Lottery Commission became embroiled in a controversy that finally caused this tension to spill out into the open. A press leak in late 1996 revealed that the Lottery Commission’s executive director, a Democratic appointee named Nora Linares, was carrying on an extramarital affair with a GTECH consultant—a major conflict of interest that provided the perfect opportunity for the Bush camp to sweep Democrats from the lottery. Miers promptly fired Linares.

And that is when a mysterious document began circulating in Austin that would serve as the Rosetta stone of the Bush National Guard controversy. The document, a single-page letter written by an anonymous author and addressed to a U.S. attorney, described an alleged secret deal struck between George W. Bush and Ben Barnes in which Barnes agreed to withhold the story of getting the governor into the Guard in exchange for Bush’s securing the GTECH contract against competing bidders.

The memo fingered a Bush aide named Reggie Bashur as the one who brokered the alleged quid pro quo: “Bashur was sent to talk to Barnes who agreed never to confirm the story and the Governor talked to [Miers] two days later and she then agreed to support letting GTech keep the contract without a bid.” And indeed, the previous summer, Miers had renewed the GTECH contract without a bid, against the wishes of state Republicans.

The memo also claimed that Bush had lied to Jim Moore when he said in the 1994 debate that he’d received no help securing a slot in the Guard. According to the memo, Barnes’s former assistant Nick Krajl had personally called General Rose on Bush’s behalf. “At this time I can’t release my name,” the memo’s author wrote, “but at the proper time I will come forward and show this story to be true.”

Initially, no one could figure out who wrote the memo. But in early 1997 Linares brought a lawsuit against GTECH for allegedly helping engineer her ouster, and her lawyer, Charles Soechting, the former chairman of the Texas Democratic party, decided to investigate the memo’s origins. He tracked it to a copy center in Austin, subpoenaed the tape from the center’s security camera, and invited some local political figures and the senior captain of the Texas Rangers to identify the man who appeared to be faxing it. Though the man wore an L.A. Lakers cap and dark glasses, witnesses all agreed it was Tom Duffy, the chief of staff for Democrat John Sharp, the state comptroller.

“Everyone in the room, in unison, started laughing and said, ‘Duffy!’ ” recalled Soechting. “Everybody knew he had one thing in life he does, and that’s take care of John.”

But why would Sharp have had the memo sent? A possible motive became clearer in hindsight: Sharp was preparing to run for lieutenant governor in 1998 against Rick Perry, who would have Bush at the top of the ballot to help him out. Sharp had also been a longtime critic of state-sponsored gaming, the establishment of which had put him directly at odds with Barnes. It would be a three-birds-with-one-stone political hit.

In an interview, Sharp told me he had nothing to do with the memo—and implicated Duffy as acting independently. “When I asked about it, he said he’s not interested in talking about it and appreciated it if I wouldn’t ask about it again,” Sharp said. “I take that to mean I’d better not ask him about it again.”

Duffy declined comment, but he was in an unusually compromised position at the time: his girlfriend was a top executive at the Texas Lottery Commission and a close ally of Linares’s.

In any case, everyone mentioned in the memo denies the story it tells. Barnes calls it “a lot of malarkey” and argues that because Rove was actively trying to get rid of him, Rove must not have feared any story that Barnes could reveal in retaliation.

Soon after, Barnes was implicated in an elaborate GTECH kickback scheme in New Jersey, where the company had another lottery contract. These allegations were eventually retracted, and the federal prosecutor who brought them was forced to issue an apology, but Barnes agreed to part ways with the company not long after. His exit package was an eye-popping $23 million. To many observers in Texas, it looked more like a payoff than a buyout. As one former Bush aide told me, “It didn’t smell right to anyone who was paying attention.”

The following year, yet another turn in the GTECH story fanned the theory that Barnes had engineered a deal to cover up Bush’s Guard history. Following Linares’s departure, the lottery commissioners decided to open up the bidding. To signal a fresh start, they hired a complete outsider as their new executive director—Larry Littwin, a short, unassuming New Yorker who had rarely set foot in Texas. He began by launching a complex investigation into illegal GTECH contributions to Texas lawmakers. But only five months after he took the post, Miers decided he’d gone rogue, stirring up paranoia among legislators from whom Bush needed cooperation on other matters and angering GTECH executives. Miers fired him without explanation, and the bidding was shut down, with GTECH retaining its contract.

Like Linares before him, Littwin sued GTECH for allegedly exerting political influence over the state agency to get him fired. To prove it, Littwin’s lawyers also focused on the alleged Barnes-Bush handshake deal described in the anonymous memo from 1996.

Legitimate or not, the timing of the Littwin suit was conspicuously poor for Bush: in 1998 he was running for reelection and laying the groundwork for a presidential run, polishing up his résumé and shaping the contours of his life into a political memoir. That year Bush’s campaign paid Miers $19,000 to examine his Guard record for “vulnerabilities,” according to a Newsweek report from July 2000. The central problem that Miers identified: “rumors that Bush had help from his father in getting into the National Guard in 1968.”

For Bush, the most irksome version of the rumor had it that his father had personally asked Barnes for help. In order to put the matter to rest, Bush sent his 1998 campaign manager (and future Secretary of Commerce), Don Evans, to talk to Barnes, who later told me, “I got the impression they were very worried.” Barnes reassured Evans, telling him that he’d never spoken to the elder Bush directly about his son. Subsequently, Barnes received a solicitous letter, signed by Bush, which is now framed in Barnes’s office: “Dear Ben, Don Evans reported your conversation. Thank you for your candor and for killing the rumor about you and Dad ever discussing my status. Like you, he never remembered any conversation. I appreciate your help.”

About a year later, after resisting a subpoena for several weeks in the Littwin case, Barnes was forced to give what would become his official version of the story: that Sid Adger, the Houston oilman and friend of the elder Bush’s, had called Barnes on behalf of Bush and asked if he could help get his son into the Guard. Soon after, GTECH settled with Littwin, paying him $300,000 and demanding that Barnes’s deposition be destroyed and that Littwin never talk about it again.

THE 2000 ELECTION

With the presidential campaign about to begin, it was now open season on the Guard story, which had still never drawn a sustained national investigation. Two TV producers pursued Barnes for his first on-air interview: Mary Mapes, Rather’s 60 Minutes producer at CBS, and David Bloom, the NBC correspondent who later died in Iraq. Mapes courted Barnes for months. Bloom spent two weeks in Austin, including a night drinking at Barnes’s estate, trying to cajole him into appearing on NBC.

Barnes basked in the attention but had no intention of elevating his court admission to a political attack. When I asked Barnes why a Democratic fund-raiser with a damaging story about the Republican presidential nominee wouldn’t help his party in the close 2000 election, he said that Al Gore didn’t ask him for help. But Barnes’s friends say he was just hedging his bets: if he told his story and Bush won the presidency, Barnes would have a powerful political enemy in the White House. (And not for the first time: Barnes believes to this day that Richard Nixon was responsible for a politically motivated investigation that led to the Sharpstown scandal and his downfall.)

But apart from Barnes, Littwin’s lawyers had inadvertently opened a second and more controversial chapter of the Bush Guard story. As part of their research, they obtained the most thorough and least redacted copy of Bush’s military file that anyone had yet seen. They obtained it not from the Texas National Guard archives, which were then controlled by a Bush appointee, but from the National Guard headquarters, in Arlington, Virginia.

Littwin’s Dallas lawyers recruited a local Air Force veteran to interpret the file. He was a Bush antagonist still agitated by medical issues from his service, but he was an expert in the military jargon of the time. “I was stunned at what I saw,” explained the man, who requested anonymity for fear of retribution. “It was full of inconsistencies.” As compensation, the man asked Littwin’s lawyers if he could keep a photocopy of Bush’s record, then made an appointment to go see someone at the Dallas bureau of CBS News. That person was Mary Mapes.

It would take her four years of obsessive pursuit—“myopic zeal,” as the special CBS panel would later describe it—to get a story on the air, but this was the exact moment when Rather’s destiny was set in motion.

A few days later, the Air Force veteran decided to contact a Boston Globe reporter named Walter V. Robinson, who was covering the Guard story. Robinson immediately flew to Texas and spent several days studying Bush’s military records. What followed was a painstaking investigation by the Boston Globe, unrivaled in its detail, which put the Bush campaign on the defensive and inspired other reporters to focus on Bush’s “lost year.”

After training at Moody Air Force Base, in Georgia—from which a military aircraft once ferried him to Washington for a date with Tricia Nixon—Bush was assigned in 1970 to flying duty as a pilot of the F-102 jet fighter at Ellington Air Force Base, in Houston. He had an apartment at the Chateau Dijon complex, an enclave of affluence where he played volleyball, barbecued, drank beer, and chased girls among the city’s oil-industry elite. He drove a Triumph sports car, his buzz cut and flight jacket obscuring his Andover-to-Yale background. An aide who worked with Bush in later years recalled his simply saying, “I was a badass back then.”

But after receiving relatively high marks as a pilot of the F-102, Bush suddenly stopped flying in the spring of 1972. Despite the declaration in his 1999 memoir, A Charge to Keep, that he flew jets for “several years” starting in 1970, his flying career actually ended two years later. That was the year he left Houston to work on the long-shot Senate bid of Winton “Red” Blount, a candidate from Alabama whose campaign manager, Jimmy Allison, was an old Bush family friend. Bush had committed to continuing his Guard service with a unit based in Montgomery, but nobody from that unit remembered seeing him, including the commander of the base. As the Globe story reported, Bush’s next documented duty in the National Guard was a year later, back in Houston. It seemed that not only had Bush avoided Vietnam by entering the Guard, but he may have simply disappeared for a spell, failing to fulfill his duty to fly planes for a full six years.

The Globe story whipped the national media into a frenzy. The gaps that it revealed in Bush’s record—and his campaign’s inconsistent and sometimes discredited explanations for those gaps—prompted persistent questions about whether he had gone AWOL or even deserted the military for a time. In particular, reporters zeroed in on a document showing that Bush had lost his flight status in August 1972 for failing to take a flight physical, a serious offense.

As it happened, another pilot listed on the same document also lost his right to fly for the same reason and at around the same time. That name was initially redacted on copies of Bush’s military record released by the Texas National Guard, even though a dozen other names on the document were not. When a clean copy turned up, the name that had been blacked out was revealed to be that of James R. Bath, a close pal of Bush’s who would later become a business adviser to the bin Laden family in Texas as well as Bush’s business partner in his failed oil venture, Arbusto Energy.

Bath declined to comment on his loss of flight status, but his military file shows that, like Bush, he didn’t fly again for the National Guard after 1972 and was discharged one year later. Many investigative reporters, fed stories by Texas Democrats, became convinced, even obsessively so, that some specific incident had occurred to precipitate this unusual coincidence. Soon every major media outlet in the country was circling around the gaps in Bush’s record.

The Bush team knew it had to respond to the stories. Campaign spokesman Dan Bartlett explained that the reason Bush stopped flying in 1972 was that he was in Alabama and his family doctor wasn’t available to give him a physical. When it was pointed out that only a military physician could perform a pilot’s flight physical, Bartlett’s story shifted. He said the Guard was phasing out the F-102 on which Bush had trained, and therefore Bush had opted out of flying altogether. Reporters countered that the plane continued to fly at Ellington Air Force Base until 1974. The Bush campaign tweaked the explanation yet again, saying that the Air National Guard in Alabama didn’t have the F-102, so he saw no reason to maintain his flight status during his transfer.

These shifting explanations only intensified the scrutiny and led to questions about what else could have caused Bush’s loss of flight status. One possible answer was offered much later, in 2004, by a woman named Janet Linke. After Bush left for Alabama, her husband, Jan Peter Linke, was transferred to Houston to replace him on the F-102, which apparently still needed pilots, despite the phaseout. While the Linkes were there, Bush’s former commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Jerry Killian, allegedly told them that Bush had stopped flying because he became afraid to land the plane. “He was mucking up bad, Killian told us,” Janet said to a Florida newspaper. (Jan Peter died in a car accident in 1973.)

But by the time Linke went public with her allegation, the press had already abandoned the Bush National Guard story for the Dan Rather controversy. Also ignored was some possible corroborating evidence: an Associated Press investigation uncovered Bush’s original flight logs, which showed that after flying for hundreds of hours on the F-102, Bush suddenly began flying a two-seat T-33 training jet and spent more time in a flight simulator in the months preceding his departure for Alabama. The logs also showed instances of his having to make multiple passes at the landing strip.

The White House said that Bush was trying to rack up required flight hours in advance of his absence in Alabama. But the flight entries in question precede Bush’s application for a transfer to Alabama.

The landing issue remains mired in ambiguous records and the selective memory of people who were there. What’s clear, however, is that Bush’s superiors made it unusually easy for him to quit flying and leave Houston. They first attempted to sign him up for a postal unit in Alabama that met once a month. (The commander of the outfit told Bush he couldn’t guarantee that the group would even exist in three months but added, “We’re glad to have you!”) When Bush was informed that he couldn’t fulfill his duty by doing that, he sent a letter requesting “equivalent duty” with the 187th Tactical Reconnaissance Group, at Dannelly Air Base, in Montgomery. The unit commander, in official memos, said Bush could start by attending two drills in September 1972. He didn’t show up for the drills.

When Bush lost his flight status, in August 1972, the official military protocol of the Texas Air National Guard was to open an internal investigation and review why the pilot didn’t show up for his physical. It says so on Bush’s own documents. That never happened.

Bush’s go-to expert on his military record, Albert Lloyd, said a report wasn’t necessary because Bush’s commanders knew he had stopped flying to go to work in Alabama—proof only that the Air National Guard blew off the rules when it came to Bush. When I mentioned this to Lloyd in 2008, he growled that “pilots hate paperwork.”

Throughout 2000, the Bush campaign sought to settle the matter of his time in Alabama, but it struggled to provide reporters with anyone who could remember seeing him there. While Bush managed to find two ex-girlfriends who would vouch for him, neither saw him in uniform, and both said that they knew of his duty only because he told them.

One man from the Montgomery unit remembered seeing Bush, but he was a political supporter in Georgia who had his details mangled, recalling Bush sightings months before Bush claims to have served there. A $50,000 reward by a nonprofit group called Texans for Truth seeking anyone who could prove Bush fulfilled his Guard duty in Alabama was never collected (nor was cartoonist Garry Trudeau’s $10,000 reward for the same information). No paper records exist in the National Guard archives in Texas or Alabama that corroborate Bush’s service in Montgomery, and the personnel officer in Alabama at the time said it was up to his counterparts in Texas to keep track of Bush. Judging by his military files, they didn’t.

Bush moved back to Houston after the November 1972 election, which Red Blount lost badly. During the holidays, he visited his parents’ house in D.C. and, after drinking with his brother Marvin, drove his car into a neighbor’s garbage can. His father demanded to see him in the den, where the younger Bush challenged his father to go “mano a mano.” The showdown, part of Bush family lore, was defused when Jeb Bush announced that George had been accepted to Harvard Business School (though he had applied only to prove to his father that he could get in, George declared indignantly).

The next month, the elder Bush was named head of the Republican National Committee. According to George W. Bush’s official time line, this was also the month that his father enlisted him in volunteer work at a nonprofit poverty program for youths in Houston’s Third Ward. It was called Project PULL (Professionals United Leadership League), and his father was an honorary board member.

In 2004 Knight Ridder newspapers interviewed several people who had worked at PULL while Bush was there. One of them, Althia Turner, fearful of telling what she knew, agreed to an interview only after a call to her pastor. She said Bush had come to the program because he had been in “trouble,” a fact she learned as the secretary to John White, the program’s founder, who died in 1988. “We didn’t know what kind of trouble he’d been in, only that he’d done something that required him to put in the time,” she said, later adding that Bush had to sign in and out of PULL offices so White could keep a tally of his hours.

Regardless of the motives behind Bush’s volunteer work, however, there is a problem with this time line. His military file shows that he didn’t return to the National Guard base in Houston until May 1973, four months after he’d supposedly started working for PULL, in January. His commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Killian, signed off on a May 2, 1973, report that said Bush hadn’t been seen for a full year: “Lt. Bush has not been observed at this unit during the period of the report. . . . He cleared this base on 15 May 1972.”

Under pressure in 2004 to explain the gap, the White House produced as evidence of Bush’s service a military dental exam from January 6, 1973—in Montgomery, not Houston. It also released a computerized summary of his pay records from the period (discovered in a Denver repository after the Bush campaign had previously declared them lost in a fire), and the dates showed that Bush was paid for attending drills in Alabama in January and again in April of 1973.

Apparently, while he was volunteering in the Third Ward in Houston, he was also pulling Guard duty six hundred miles away, in Montgomery—or at least getting paid for it—despite the fact that his home base, Ellington, was right across town.

Compounding the mystery, one of Bush’s ex-girlfriends, Nee Bear, who worked on the Blount campaign and later moved to Houston and dated Bush in the summer of 1973, said she never saw him in Alabama after the election. She claims she would have been aware had he returned. “We would have all known about it,” said Bear. “We all kept in touch.”

In 2004 White House spokesman Scott McClellan very carefully answered questions about this period with the time-blurring catchall statement, “He does remember serving in Alabama and Texas. During that entire time, he was a member of the Texas Air National Guard.”

Here’s what we can say for sure. In the spring of 1972, Ellington Air Force Base was becoming a hub for pilot training. Bush could reasonably argue, as he did, that fewer planes were available for him to fly, and he opted against training on the next generation fighter, the F-101.

That explanation, however, doesn’t negate the other evidence but rather dovetails with it: as the Vietnam War wound down and Bush became less and less focused on flying (his annual performance review turned distinctly lackluster in 1972, and Bear said Bush was “terribly adrift” when she first met him in Alabama), an opportunity to duck out presented itself and he took it. There were ten other pilots who dropped out that same year—all much older men who had more than two decades’ worth of experience. That Bush’s commanders let the young pilot bow out early and arranged the paperwork accordingly wasn’t necessarily nefarious, but just the way things worked in the loosely regulated fiefdom of the Texas Air National Guard in 1972, especially for a son of wealth and power like Bush. Pilots didn’t like paperwork—and neither did National Guard commanders who coveted political influence in Texas.

This story, taken as a whole, isn’t particularly damning; it was typical for young men of Bush’s social standing. But it fundamentally undermines an element of Bush’s political identity: the “badass” jet pilot for whom flying was a “lifetime pursuit,” as he once put it. And because of Bush’s stonewalling on the issue, the power of the unanswered questions about this period of his life would take on a life of their own.

Case in point: a story that seemed to tie together all the questions hanging over Bush’s Guard service appeared in the controversial book Fortunate Son, by J. H. Hatfield, during the 2000 campaign. In the book, Hatfield made the incendiary claim that Bush had been arrested in 1972 for cocaine possession but had had his record expunged through his father’s political influence with a state judge in exchange for community service at PULL. (The book also claimed the arrest file was stowed in a safe in Harriet Miers’s law office in Dallas.)

This story did a lot of work: it explained why Bush stopped flying, why he lit out for Alabama, and why he ended up at PULL when he got back to Houston. Within days of the book’s publication, however, a newspaper discovered that Hatfield had served five years in prison for hiring a hit man to kill a former colleague. The publisher, St. Martin’s Press, quickly pulled the book from the shelves, and, under pressure to reveal his sources, Hatfield claimed that Karl Rove himself had confirmed the story during a fishing trip. Rove denied all such claims. A small publisher in New York later reissued the book, offering as evidence of Hatfield’s honesty some phone records showing a two-minute call to Rove’s home before the original publication.

A year later, Hatfield died of a drug overdose in an apparent suicide. Hatfield’s defenders came to believe he’d been set up by Rove as the dupe messenger who could be easily destroyed. And with that, the Bush Guard story officially took on the dark aspects of a conspiracy: a puzzle in which the missing pieces became the story.

THE 2004 ELECTION

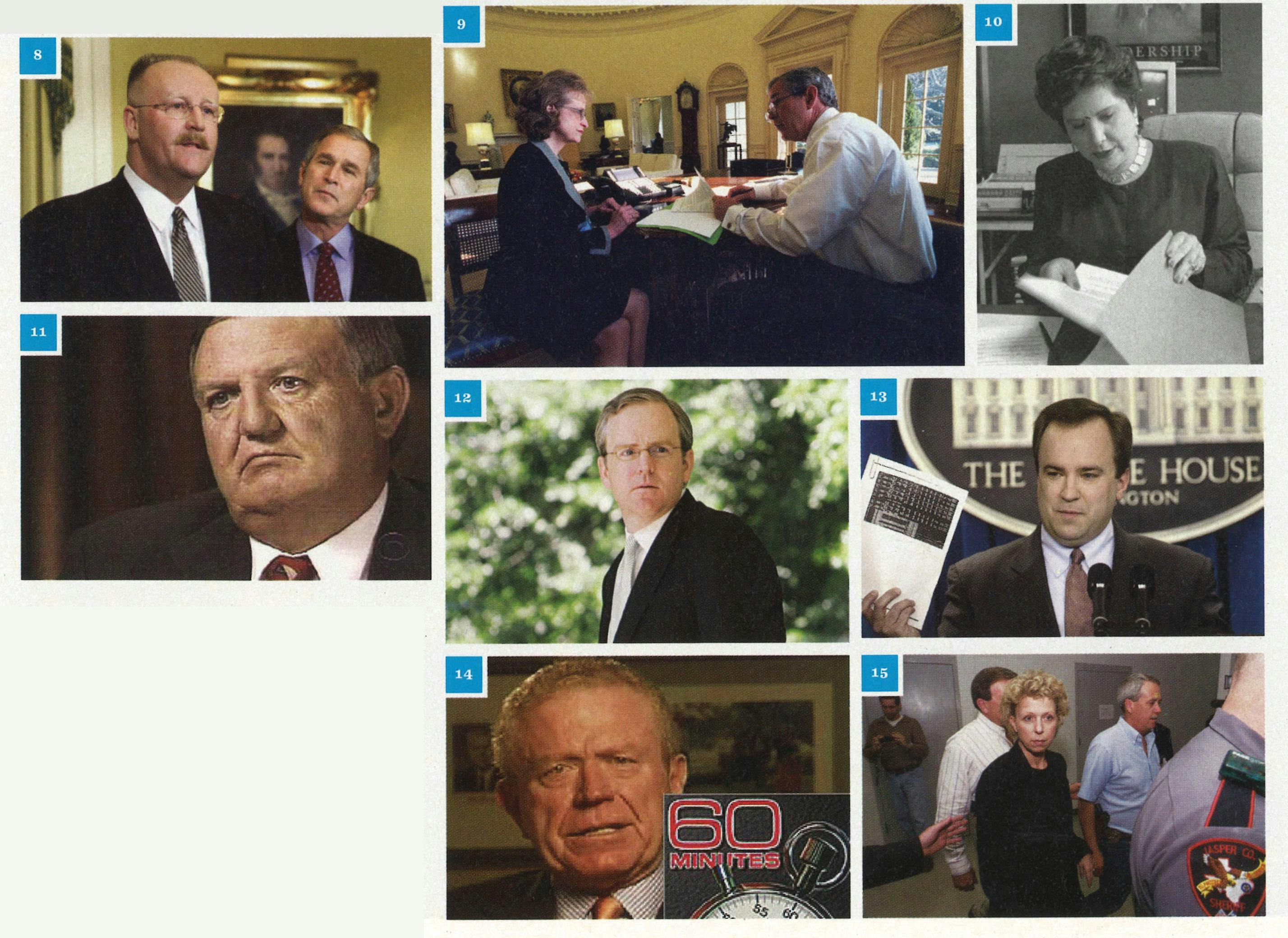

By 2004 Dan Rather was the lowest rated of the three network evening-news anchors. He had, over the years, established himself as a reliable bogeyman for the Republican party—and for George W. Bush in particular. That spring, he and Mary Mapes broke the story that U.S. soldiers had tortured prisoners at Abu Ghraib, seriously tarnishing Bush’s war in Iraq. And Mapes had yet another story in the pipeline: ever since the Air Force vet had dropped off Bush’s military file at CBS News in Dallas, in 1999, she had been accumulating documents and interviewing retired Guard employees, building a case that Bush had received preferential treatment and possibly gone AWOL.

But Mapes wasn’t the only one who had continued to develop the National Guard story. One of the journalists working the story throughout Bush’s ascent from governor to president was Jim Moore, the KHOU TV reporter who’d originally asked Bush about his service during the gubernatorial debate in 1994. Now, ten years later, Moore published everything he’d found in a book called Bush’s War for Reelection. Among other things, the book publicized the claims of Bill Burkett, a grizzled lieutenant colonel in the Texas National Guard who said that in 1997 he had overheard Bush advisers Joe Allbaugh and Dan Bartlett asking Bush’s top Guard appointee in Texas to dispose of “embarrassments” in Bush’s file. (Allbaugh and Bartlett deny this.) Burkett also said he later saw some of Bush’s military records in a trash can.

Under media scrutiny, Burkett, a yellow-dog Democrat, changed important details of his story, and Bush aides easily dismissed him as a disgruntled Bush hater, who was angry over medical bills the National Guard refused to pay. But he had just enough of his facts straight to make his claim plausible. For one, the papers he said were destroyed were the same ones that reporters found to be missing, including performance reviews and pay records from Bush’s later years in the Guard.

And Allbaugh and Bartlett had indeed been assigned to manage the National Guard story. Bartlett, who began working for Karl Rove when he was 23, became Bush’s liaison to the Texas National Guard during the year Burkett said the files were scrubbed, and he later assisted Harriet Miers in her firm’s examination of Bush’s military file in the lead-up to the presidential run.

The current archivist of the Texas National Guard, James Shive, told me that he personally examined Bush’s file in 1992, before Bush ran for office, and found nothing damning in it. He did say, however, that Bush’s file had “unusual” gaps in it, referring in particular to an annotated history of his time in the Guard, typed up in the early seventies, that didn’t record Bush’s loss of flight status or any subsequent reassignment. But a scrubbing incident by state officials as late as 1997, he said, wasn’t plausible. Instead, Shive questioned whether anything negative would have been inserted into Bush’s record to begin with, given the political influence of his father in the early seventies.

Burkett’s allegations nonetheless spurred probes by several news organizations. In February 2004 he was invited on MSNBC, where he was asked by Chris Matthews whether he was willing to testify under oath that Bush’s aides discussed destroying his military records. Burkett’s reply was tricky: “I’m swearing to you on camera, and I’m swearing to the American people. And God is my pilot on this. And I have sworn this all along.”

The scrutiny on Bush’s past increased. Later that month, under pressure from Tim Russert on NBC’s Meet the Press, the president told the host he would release his entire military file, including pay records. But the release of pay dates from a computer database only spurred more questions: Why didn’t the pay records from 1973 match Bush’s official biography?

At first, White House spokesman Scott McClellan dismissed the attacks as attempts to stir up old news, pointing out that the Democratic National Committee had launched a special investigation called “Operation Fortunate Son,” which he noted was “the name of a book by an ex-convict that was widely discredited in the 2000 campaign.”

But McClellan had no idea what he was talking about. While trying to field press queries, he had asked Dan Bartlett, who had a thick notebook dedicated to the Guard issue, if he could study the book to help defend the president’s record. “He said, ‘No, I think you’ve got everything you need,’ ” recalled McClellan. “I didn’t have all the facts. I would have preferred to look at the records myself, but I was denied access. So most of what I had was either what I was told by Dan or what the president confirmed in the presence of Dan.” Bartlett, he said, “probably remembers better than the president.” McClellan explained that a tight lid had been kept on the Bush National Guard issue, with access limited to Rove, Miers, and Bartlett. “It raises questions when you’re not open and candid about things,” McClellan said, “and this is something that has been closely held for a long time.”

(When I asked Bartlett about this, he explained that the notebook “wasn’t a formal dossier. It was a mixture of crib notes I’d taken over the years. It made sense to me, but not to other people.”)

Bush and his inner circle didn’t want to help the press expand on the Guard issue; they wanted it to go away. So when the Associated Press sought additional documents, the Pentagon denied the news agency for several months. The AP was forced to sue both the U.S. Department of Defense and the Air Force for access. Even then, the White House pushed back: in a phone conversation with the AP’s Washington bureau, Bartlett questioned the political leanings of the AP’s lawyer, David Schulz, detailing his Democratic campaign contributions. “Why in the world is the AP using a liberal lawyer?” Bartlett asked, according to Schulz. Bartlett then suggested the AP was letting Senator Kerry off the hook. “It was all-out war against the AP,” recalled Schulz.

But the AP’s efforts ultimately unearthed Bush’s flight logs, which prompted new questions about the abrupt end of his flying career. John Solomon, the editor who headed the AP’s investigation and later became the executive editor of the Washington Times, said, “There was one big question left unanswered. He had been flying in a regular fighter jet for quite some time and scoring well, then this abrupt shift, and suddenly he dropped back to the trainer’s plane, which experts told us was very unusual. That was one of those unresolved questions.”

But before those questions would have their day, another report would blow them off the map.

In August 2004 the Guard story suddenly became vitally important to Senator Kerry’s campaign because of the blistering attacks on his Vietnam service by the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth. A related book, Unfit for Command, co-written by John O’Neill and conservative writer Jerome Corsi, questioned whether Kerry’s Purple Hearts and Bronze and Silver Stars were legitimate, calling him “a liar and a fraud.” After two weeks of attacks, Kerry was desperate to strike back. At a campaign meeting on his wife’s farm in Pennsylvania, he tapped a member of his finance committee whom he believed could help him retaliate: Ben Barnes.

Kerry knew that in a private fund-raising speech earlier that year, Barnes had told how he visited the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington one night and grew ashamed at having helped sons of privilege into the Guard while others died in their places. He knew that in the same speech, Barnes had recounted for the first time since the Littwin deposition how he’d personally helped Bush avoid Vietnam at the request of Sid Adger.

After the campaign meeting, Kerry grabbed Barnes’s arm. “You’ve got to help me,” he said. “What are we going to do about this?”

That’s when Barnes agreed, five years after Mapes began trying to persuade him, to finally tell his story on 60 Minutes. Two weeks later, Mapes finagled a meeting with Bill Burkett to acquire what looked like another bombshell scoop: a set of never-before-seen memos about Bush’s Guard career that seemed to fill in the blanks. They were said to be from the personal files of Bush’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Jerry Killian, dating from the spring of 1972 to the late summer of 1973. One of them, a typed letter labeled “CYA” (Cover Your Ass), from August 1973, had Killian describing the political pressure he was under from Buck Staudt to “sugarcoat” one of Bush’s performance reviews even though there was no evidence that Bush had fulfilled his duty. “I’m having trouble running interference and doing my job,” the letter said. “Staudt is pushing to sugarcoat it. Bush wasn’t here during rating period, and I don’t have any feedback from the 187th in Alabama. I will not rate. Austin is not happy today either.”

Over several days of questioning, Burkett told Mapes he’d gotten the documents from a former Guard colleague named George Conn, who had previously vouched for Burkett’s credibility in press reports. But Mapes never found Conn to corroborate the story. And document analysts hired by CBS were conflicted over the authenticity of the documents, unable to confirm Xerox copies with 100 percent accuracy. There were other niggling issues: Staudt, who allegedly pressured Bush’s commanding officer in 1973, was no longer the head of the Guard at the time (later Mapes would argue that Staudt still wielded influence, even after he retired).

Solomon, the AP editor, told Mapes that new documents were about to emerge from the AP’s lawsuit, but CBS was under competitive pressure to air its report as soon as possible. USA Today, after courting Burkett for three years, was on the verge of also obtaining the four controversial memos said to be produced by Killian.

The morning before the broadcast was scheduled to air, CBS showed the memos to the White House for a response. Dan Bartlett was the network’s contact. Before Bartlett was interviewed, he emailed copies of the memos to Albert Lloyd, Bush’s longtime National Guard expert. In an interview in 2008, Lloyd told me he immediately recognized them as forgeries: “I looked at them and I said, ‘Don’t do a damned thing with these, because these are fake.’ ”

Bartlett, however, appears to have ignored Lloyd’s assessment. When asked by CBS whether he doubted the authenticity of the memos, Bartlett replied, “I’m not saying that at all,” adding that he only questioned the timing of their release. His interpretation of the memos, in fact, was that they “reaffirm what we’ve said all along.”

And so, on September 8, Rather’s report aired on the Wednesday edition of 60 Minutes.

The first person to publicly question the memos was an Air Force officer in Montgomery named Paul Boley, who posted on the conservative online forum Free Republic under the handle TankerKC. Boley’s comment popped up while the program was still going on.

But the man officially credited with inspiring a fusillade of blog attacks was Harry MacDougald, known on message boards as Buckhead, a GOP lawyer in Atlanta who missed the segment but downloaded the Killian documents from the CBS website later that night. He specifically claimed that the memos used proportional spacing and superscripts that didn’t exist on typewriters of the early seventies.

A conspiracy theory has since arisen that Bartlett, knowing in advance that the documents were forgeries—and, in some fevered imaginations, knowing his boss Karl Rove was the source of them—tipped off right-wing surrogates to attack the documents.

When I asked Lloyd why Bartlett ignored his assessment, he said, “I guess he was trying to set Rather up for getting mauled.”

Bartlett told me that the online attacks began “before I started any outreach” to the press. He added that Bush himself didn’t learn of the Killian memos until after the segment had already aired, because Bartlett felt the documents didn’t show anything revelatory. He initially dismissed them as “old news.”

In any case, MacDougald’s arguments about the documents turned out to be inaccurate. He acknowledged as much in an interview with me in 2008. And in a speech given that same year, Mike Missal, a lawyer for the firm that CBS hired to investigate its own report, said, “It’s ironic that the blogs were actually wrong. . . . We actually did find typewriters that did have the superscript, did have proportional spacing. And on the fonts, given that these are copies, it’s really hard to say, but there were some typewriters that looked like they could have some similar fonts there. So the initial concerns didn’t seem as though they would hold up.”

Nevertheless, the controversy exploded in the press, catalyzed by a report in the Washington Post that aggregated all the criticism from the blogosphere and laid it at the doorstep of Rather and CBS. Bartlett coordinated with several former Guardsmen, including Killian’s son, to follow suit and attack the CBS report.

Rather was forced to respond, giving newspaper interviews defending the report and eventually addressing the controversy directly on the evening news, offering up new interviews and evidence meant to buttress his initial claims (most famously, he interviewed Killian’s former secretary, who said the content of the memos was accurate but the memos themselves were fake).

The day after the CBS broadcast, USA Today published the exact same memos in a news report. But instead of going on defense, as CBS did, the newspaper responded to criticisms by getting Burkett to reveal himself and explain how he had come by the documents. The explanation was like something out of a Carl Hiaasen novel: Burkett said he’d received a call from a woman named Lucy Ramirez, who saw him on MSNBC. They arranged a secret handoff of documents at a cattle show in Houston. A man in a cowboy hat gave Burkett a manila envelope. The instructions, claimed Burkett, were to copy the memos inside and burn the originals so there would be no DNA evidence to identify the true source. USA Today scoured the country for a “Lucy Ramirez” fitting Burkett’s description (he said she’d called him from a Holiday Inn), but no such person was ever found.

While trying to sort fact from fiction, CBS kept defending its report. After twelve days of intense pummeling by conservatives, the network finally gave up the ghost and forced a frantic and exhausted Rather to apologize. The president of CBS, Les Moonves, promised Rather he’d survive the fallout. A special panel was established to investigate errors in the story, but before the panel report was completed, Bush won reelection. The Swift Boaters had waylaid Kerry, but Democrats were never able to return to the Guard story as a legitimate line of attack against Bush. “After the Rather thing happened, [it was] pretty tough to carry the story politically,” said Jason Miner, who was an opposition researcher for the DNC tasked with bringing Bush’s Guard record to the press’s attention. “Who’s going to stand up there?”

Walter V. Robinson, the Boston Globe reporter whose 2000 investigation had triggered much of the subsequent reporting, agreed. “The CBS story, and the furor that caused, buried the story so deeply that you couldn’t possibly disinter it in 2004,” he told me. “Inevitably, the only candidate who ended up with a serious credibility problem about his military service was John Kerry, who had absolutely nothing to hide or be ashamed of. To me, in a close election—and it was a close election—who knows, that could have been the difference.”

![feat_TorCRather-Promo]() THE LEGACY

THE LEGACY

When the panel report finally came out in January 2005, it did not determine whether the documents were real, but it did blame Mapes and three other CBS producers for failing to properly vet them. CBS fired Mapes and asked the three others to resign. All three threatened to sue and were subsequently paid settlements to stay quiet about the story.

Rather was spared (a humiliating forensic examination revealed his virtual absence from the reporting process), but he agreed to resign from the CBS Evening News in the spring. Mapes went home to Dallas and began writing her book-length defense.

But the CBS episode wasn’t quite the end of the Guard story. There was a bizarre postscript: the failed nomination of Harriet Miers to the U.S. Supreme Court in 2005. One year after the fateful 60 Minutes segment aired, two FBI agents paid a visit to the Manhattan apartment of Larry Littwin, the former Lottery Commission executive director. If he were cleared to testify before the Senate Judiciary Committee, the agents asked, what might he say about Miers’s involvement with GTECH during her time as chair of the commission? According to Jerome Corsi, who had resurfaced, post-Kerry, as one of Miers’s fiercest critics, what Littwin proposed to allege was quite a lot: that more than $160,000 in legal fees Miers collected from Bush in the nineties were a de facto payoff for maintaining the quid pro quo agreement with Ben Barnes and GTECH.

Regardless of the legitimacy of these allegations, White House officials were paying attention, in part because they were coming from the right. Miers’s nomination was already in deep trouble by the time Littwin emerged. But Corsi remains convinced to this day that the threat of Littwin’s testimony was the last straw for Miers. According to him, it was the GTECH deal, and not the CBS memos, that could have been the real smoking gun against Bush. “The day after they validated that Littwin was going to be called to the Senate Judiciary Committee, that’s when she pulled her nomination,” Corsi told me.

In 2007 Rather filed his own lawsuit, implicating Viacom chairman Sumner Redstone and CBS president Les Moonves in a vast corporate cover-up to make the Guard story go away, placate the Bush White House, and put a troublesome newsman out to pasture. He asked for $70 million. The money, however, was largely symbolic. More than anything, Rather hoped the lawsuit would finally prove that he had been unfairly hung out to dry.

When it was dismissed, in 2009, he was devastated. He maintains a smoldering anger for CBS News. But Rather says he remains “optimistic” that somebody, somewhere, will one day come forward and reveal the truth of what happened. “They’re out there,” he says. “Let’s set the record straight.”

And what about George W. Bush? It’s unclear how the curators of his presidential library, which is slated to open next year at Southern Methodist University, will treat the ex-president’s life from 1968 to 1973. They’re unlikely to explore the finer details of his flight logs or offer any further information about his “lost year.” But his time flying planes in Texas during the height of the Vietnam War remains a defining part of his political biography nonetheless, a chapter he proudly referenced in 2003, when he landed in a jet plane on the deck of an aircraft carrier to declare the end of major combat operations in Iraq—right before the country sank into a bloody, years-long war that would divide the United States and claim tens of thousands of Iraqi and American lives. Bush has said history will be the judge. And so it will.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Longreads

- George W. Bush

- Dan Rather

- Ben Barnes

THE LEGACY

THE LEGACY