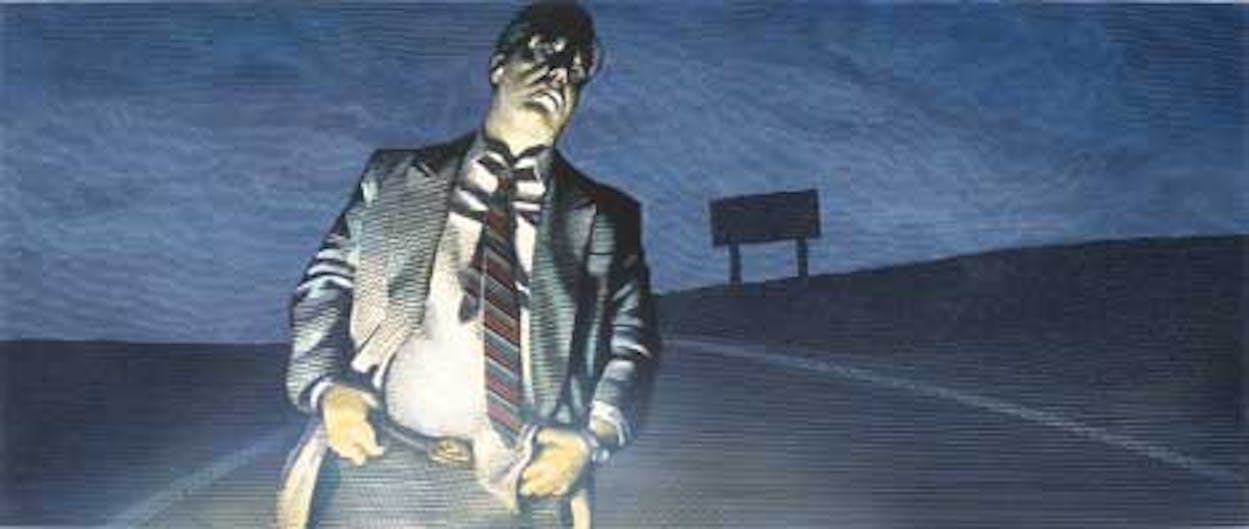

Baldwin wished he could have mustered a bit more surprise when the dead man rose from the road in the sheriff’s headlights. The sheriff shook his head in disgust, stood on the brakes. His bumper stopped a good quarter inch from Alexander Johnson III’s kneecaps. The banker looked from the front of the cruiser to its windshield, his eyes flat. Somebody else must’ve been wearing his toe tag at the morgue. A tried-and-true scam, sure, musical corpses, but had Newby been in on it, or was he just in it the same way Baldwin was? A wrong-place, wrong-life kind of thing? Nothing new there.

The sheriff groaned, climbed out from the cruiser, slung the door shut behind him. Baldwin knew better, but he tried the door handles to either side of him all the same. If the sheriff would just step away, he could kick one of the plastic windows out. But they were both looking at him now. Studying him. Worse—liking what they saw. When the dead man opened his mouth to say something, though, the sheriff hustled him out of earshot.

Baldwin laughed to himself. Like he gave half a rat’s ass. What was important right at the moment was what was always important when he got cornered, be it by cellmates, roughnecks, or ex-girlfriends: Live, escape, get away. It hadn’t failed him yet.

Except.

Baldwin didn’t want to admit it, but this time it was looking more and more like the only way out was going to be to dive right into the middle, grab the thing by its grubby heart.

And that heart—it was green, it was an emerald.

He had to get to that safety-deposit box in Odessa before the rest of them. Come sunup—no, come ten minutes after the bank opened—this was all going to be settled, one way or another. The reporters would can their versions of what hadn’t really happened and be on their way to the next big lie.

It was all going down tonight, whatever it was.

Problem was, aside from being locked in the backseat of a cruiser, he’d also seen the dead man getting some night air. It gave Baldwin a strong suspicion not just that his days had numbers but that his hours did too.

“Welcome to Texas,” Baldwin muttered to the inside of the cruiser, and crooked himself across the seat as best he could, pushed the heel of his boot once against the window.

Now or never. He set his teeth, turned halfway, and—

“You think you’re the first one to ever try that?” a voice came on, all crackly around the edges and distinctly female.

Baldwin redirected at the last moment, slammed his heel into the door panel.

“Was hoping to have met you back at the picture show,” he gambled, sitting up and glancing all around. “Maybe check out the cheap seats up in the balcony.”

Wherever she was, she didn’t hear him, couldn’t; the mike was still keyed on. Baldwin shook his head, leaned back against the seat.

“Just here for the ride, lady,” he said, and was about to repeat it, make it his chorus—she couldn’t hear anyway—when the night got cut open twice in a row, little slits that showed its burning orange insides.

Gunfire.

Baldwin leaned over, out of the way of whatever stray lead might be buzzing around.

Who got it? Who gave it?

Then another shot, whiter this time around the muzzle, and from lower, almost on the road.

Baldwin hunkered down a bit more, wanted to close his eyes but was thinking all the wrong things: how he’d taught his boy to suck up his cartoon-cereal milk with those 20-gauge McDonald’s straws; the distinct sound a .30-caliber rimfire slug makes when it slaps deer flesh; a little girl with no name, standing in her best clothes, the shadow of a flagpole cutting across her; Carla when she’d been Connie, dancing slow with him at the bar, her head on his chest like they were about to grow old together.

And something she’d said into his shirt. Right when the door of the bar had opened, then stayed open, as if someone was just standing there, watching them.

Baldwin couldn’t tell who it was, probably hadn’t known, so he tried instead to settle back on Carla, whispering into his chest.

It wasn’t so much what she was saying, though.

Her hands, they’d started up at his neck, looped the way girls do, but were finding their way down his sides, to his belt. The right rear pocket of his jeans.

What had she put there?

Something that wouldn’t show up on a half-assed pat-down.

Baldwin pushed his heels against the floor, stood up a little, and felt into his pocket. Sure enough. This why Newby’d had his pants off?

Baldwin almost laughed, except now the car door was opening. Not sheriff-style either, all at once and mostly pissed off. This was more like a ghost might enter. Tonight was full of them.

“Hello?” he said.

Sally unfolded herself into the driver’s seat. She of the unmerry Christmas card. Twin Wells’ shy projectionist. Grieving widow, presumed dead.

She eased the door shut, then set her radio down on the passenger seat, all the static in the car getting sucked back into the stratosphere. She adjusted the rearview so her eyes and Baldwin’s met.

“So she gave it to you, right?”

Baldwin chewed his lip, looked away. Out to what he knew he’d be able to hear if the window were down: the tapered back of a boot heel scraping slower and slower against asphalt, a prayer sloshing around in a throat already too full of other things.

“I hate this place,” he said. “Twin Wells. It always like this?”

“You don’t know the half of it,” she said, cracking the window a touch, ratcheting the seat up. “But I’m pretty sure I asked you a question there.”

Baldwin shrugged.

“You’re alive,” he said. “I think that means I probably can’t be charged with killing you, at least.”

She laughed and lit up a long brown cigarette, same as Belly smoked. Baldwin cringed. Dropping the cruiser into reverse, she said, right into the mirror, “The night’s still young, plowboy. And it’s a ways till dawn. You can trust me on that.”

Baldwin huffed a laugh out his nose, settled down into his seat even more, and watched as the fence posts began to whip by. Soon they were replaced by telephone poles, the longest run of telephone poles he’d ever seen. Finally they reached the outskirts of Odessa, the glass front of a bank, where Carla reached down to open his door, the same hungry shine in her eyes Sally’d had for the whole ride.

No surprise there.

NEXT MONTH

The final chapter, by Elmer Kelton, in which . . .