Baldwin leaned against the counter, thumbing through the photos of Sally Johnson. He kept returning to the shot of her in Newby’s bedroom, naked, posing coyly in a quarter turn from the lens. She was a young forty: wiry and tanned; hair the color of yesterday’s coffee, mussed out of a spray-stiffened updo; eyes happily crowfooting; lips in a crooked half smile. Baldwin had an urge to tuck the photo into his pocket, but he caught himself when he heard Katherine’s voice in his head: You’re ogling a dead woman, Clay. Show a little damn character for once.

A squeal of brakes outside startled him, and he dropped the photos on the floor as another memory from his blackout night rose up: sitting behind the wheel of Newby’s truck, his free hand around a sweaty can of Lone Star, his attention drifting to a jeweler’s magnifying lens swinging hypnotically at the end of a lanyard that dangled from the rearview. Newby sitting shotgun, caressing the loupe between thumb and forefinger, muttering, “Show me truth from lies, baby.” A woman’s laugh from the backseat. And then: a blue heeler darting out from a patch of tall grass. That biting wail of brakes. A crazy fishtail, then two quick, bassy thumps: bumper lifting dog, dog slamming high up on the passenger side.

So he had killed that lady’s dog out by Johnson’s place. God. What else had he done?

Stop. Time to move, time to quit taking dumb chances. In the back room, his boot heels crunched over the glass that speckled the floor. He was about to toss the Louisville Slugger aside and hoist himself up to the broken window when he caught a whiff of a familiar smell, pungent and ammoniacal.

On one wall, a cheap, bought-at-the-border blanket hung from eye level to the floor. He pulled the blanket aside, revealing a hacked-out passageway into the closed-down movie theater next door. At the far end of the dark hall, a doorway was framed in a flickering silvery glow. Against his better judgment—if, in fact, he had any such thing at all—he made his way up the hall, through the murk, and into the meth-lab stink.

Baldwin stayed in the shadows as his eyes adjusted to the light from the screen. All the seats were empty, the ones that were left anyway; the last five rows had been torn up, replaced by tables covered with jugs and jelly jars and two-liter bottles. On the floor were coils of tubing and buckets and a propane tank and a knee-high pile of trash. No ventilation pipes. A bush-league operation. Like Newby was trying to blow himself up.

On the screen a blonde girl on a diving board was stripping off her clothes. There was a crackle in the speakers and a yip of feedback as a mike went live. Baldwin glanced up at the projection booth and saw movement in the shadows. A woman’s voice—scratchy and whiskey-rough—came through the speakers. “Where’ve you been?”

There was silence. Baldwin didn’t fill it.

“Wait,” the voice said. “Is that you?”

“Probably not,” he said.

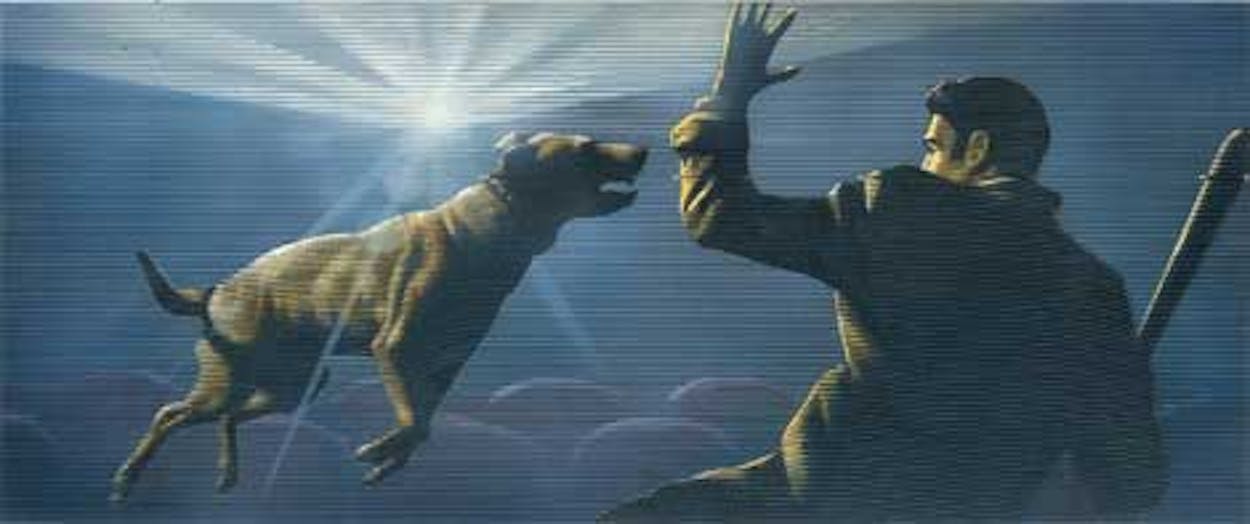

He heard a door fling open and someone running. Then: fierce barking, a mad jangle of collar tags, paws pounding, locked in on him and closing fast. He set his feet and cocked the bat, but when the crazy-barking, drool-flinging hundred-pound pit-bull projectile hurled itself out of the darkness, Baldwin’s mind flashed him an image of the heeler jumping in front of the truck, and he swung late. Teeth sank into his leg, jaws clamped and shook, and Baldwin fell, his whole world swallowed in a fire-red burst of adrenaline and pain.

When he awoke, the theater’s houselights were on, the screen was dark, and a woman was tightening a bandanna around his calf. He recognized her immediately: his dance partner from the blackout night. She had traded her vinyl skirt for jeans and a T-shirt that said “Work Sucks—I Want a Margarita.”

“Connie?” he said. “Corinne?” He wasn’t good with names, especially not names he’d learned in bars.

“Carla,” she said.

“I knew that.”

“You haven’t gotten it right yet. Not even when your pants were off.” She smiled. “Dogs don’t do so well around you, do they?”

Baldwin felt dizzy and vague. The air in the theater was a thick swirl of solvent fumes. He turned to one side and saw the pit bull’s body, blood trailing from a head wound and masking its snout. Next to it was the bat. The blood on the lacquered ash gleamed under the lights.

“I killed him?” he asked softly.

“Don’t go stealing credit,” Carla said. “I always knew that dog was trouble.”

“You didn’t set him on me?” Baldwin asked.

“I just followed you in.”

Baldwin pondered this. “I ain’t looking for a relationship,” he said, finally.

“Me neither. I’m looking for the emerald.”

“You won’t find it on me.”

“I know,” she said. “I already checked.”

Things weren’t adding up. “So who was that in the booth?” he asked.

Carla tore open a wet nap packet and scrubbed at the blood on her hands. “Sounded to me like Sally Johnson’s voice.”

“Sally Johnson’s dead,” Baldwin said. He didn’t add: And I’m the one who killed her, probably.

Carla eyed him closely. “Can I trust you?”

“I guess,” he said, even though most people who knew him would disagree.

“I need your help getting my son away from this place,” she said.

“Who’s your son?”

“Mookie.”

“You know I’m not good with names,” he said.

She reached into a brown bag on one of the tables and pulled out the garish yellow SpongeBob doll. It had been sliced open down the middle. Little tufts of stuffing fell out.

“Oh,” Baldwin said. “That Mookie.”

Main Street was clotted with cameramen and blow-dried correspondents wielding microphones and spotlighted locals delivering the requisite shock and tears. Baldwin slipped down an alley. Carla had told him to get cleaned up and meet her at the bar in an hour. She’d explain everything, she said: about Joe and Sally and Alex and herself, about their 25 years of rivalries and betrayals and schemes and secrets, about a priceless Colombian emerald with a weird Persian name.

A stiff wind pushed at him, and he shivered. How the hell had it gotten so cold so fast? He leaned up against a brick wall to rest and was thinking dreamily about the hot shower awaiting him at the motel when a long black sedan pulled up.

“Hop in,” the sheriff said. “Ice storm’s coming quick.”

“I’ll be fine,” Baldwin said.

“Not if you don’t hop in,” the sheriff said. He raised his gun just high enough for Baldwin to see.

It was warm inside the car. Baldwin stretched out on the backseat, which was covered by a blanket. The blanket smelled like dog, which did not seem like a good omen at all. Neither did the things that he spied in the passenger seat: a stack of official-looking papers with Baldwin’s own signature on the top sheet and, at the end of a neatly coiled lanyard, a jeweler’s loupe.

Next month:

Chapter Ten, by Diana Lopez, in which Baldwin takes an illuminating ride out past the city limits.